Rivers of Time is a 1993 collection of science fiction short stories by American writer L. Sprague de Camp, first published in paperback by Baen Books.[1] All but one of the pieces were originally published between 1956 and 1993 in the magazines Galaxy, Expanse, The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, Analog, and Asimov's Science Fiction, and the Robert Silverberg-edited anthology The Ultimate Dinosaur. The remaining story was first published in the present work.

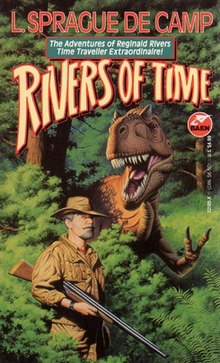

Cover of the first edition. | |

| Author | L. Sprague de Camp |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Bob Walters |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Science fiction |

| Publisher | Baen Books |

Publication date | 1993 |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | Print (paperback) |

| Pages | 258 |

| ISBN | 0-671-72195-X |

| OCLC | 29138676 |

| LC Class | MLC R CP01173 |

The book collects the author's nine tales[2] of time-traveling hunter Reginald Rivers, the hero of his 1956 classic, "A Gun for Dinosaur". He wrote another Rivers story in 1990 to fulfil a request by Robert Silverberg for a dinosaur story for his 1992 anthology The Ultimate Dinosaur; afterwards, de Camp added to the sequence until he had enough stories for a book.

In 2012, Audible Studios released an unabridged audio-book recording of Rivers of Time narrated by James Adams.[3]

Contents

edit- "Faunas" (poem)

- "A Gun for Dinosaur" (from Galaxy Science Fiction, March 1956) – Rivers explains to a client the reason for his policy of only taking clients able to handle a heavy-caliber gun back to the late Mesozoic, with a hair-raising narrative of what once happened when a client could not. This story was adapted for radio in the NBC series X Minus One on March 7, 1956.

- "The Cayuse" (from Expanse #1, 1993) – Reggie tells the story of the only time they tried to bring a manned vehicle back to the prehistoric days, during which the gas fumes acted like a mating scent for a Parasaurolophus, resulting in the vehicle's subsequent destruction in a river.

- "Crocamander Quest" (from The Ultimate Dinosaur, October 1992) – Misadventures bedevil a trip to the age of amphibians, especially when the divorced wife of one of the sahibs (who has accompanied her ex on the time trip) starts getting too flirtatious with the other party members.

- "Miocene Romance" (from Analog Science Fiction and Fact, January 1993 (as "Pliocene Romance")) – A female animal rights activist stows away on a time safari chartered by a father and son to prevent anyone from shooting the animals, enraging the father and intriguing the son.

- "The Synthetic Barbarian" (from Isaac Asimov's Science Fiction Magazine, September 1992) – A client whose motive for chartering a time expedition proves to be personal wish-fulfillment gets more than he bargained for.

- "The Satanic Illusion" (from Asimov's Science Fiction, November 1992) – A challenge from religious fundamentalists to prove the theory of evolution through a time travel expedition serves instead to demonstrate the infinite capacity of the human mind for self-delusion, even if it has to involve murder.

- "The Big Splash" (from Isaac Asimov's Science Fiction Magazine, June 1992) – An expedition to chronicle the K-T event and resolve rival theories about its cause nearly makes the time-travelers participants in the great extinction.

- "The Mislaid Mastodon" (from Analog Science Fiction and Fact, May 1993) – After a successful "bring-'em-back alive" expedition to retrieve a mastodon from the past to the present, subsequent events prove disastrous. The plot feature of a disaffected businessman's designs on a recovered prehistoric proboscidean echoes de Camp's much earlier story "Employment" (1939).

- "The Honeymoon Dragon" (original to the collection) – Rivers and his wife visit his native Australia, where they themselves guests on another time safari operation. The trip proves more dangerous than they expect when a fellow time-traveler with an inexplicable grudge against Rivers turns the expedition into a deadly trap.

- "Afterword" – A brief resume from the author on how the stories in the book came to be written.

The series

editThe Rivers stories take the form of first-person narratives by the protagonist told to companions whose identities vary, but who have in common the fact that their contributions to the conversation are omitted, and must be inferred from those of Rivers. Every story is an anecdote from Rivers' career as a conductor of time safaris to previous eras, both to hunt prehistoric creatures and for scientific purposes (and, occasionally, anti-scientific purposes). In addition to Rivers, the main recurring characters include fellow members of his safari firm, including his partner Chandra Aiyar, camp boss Beauregard Black, and cook Ming. In most instances, the actions of their human clients prove more troublesome than those of the extinct fauna, a theme set in "Faunas", a 1968 poem by de Camp that precedes the stories. An afterword by the author tells how he came to write the series.

Rules of time travel

edit- The effective range of the stories' time machine is from about one hundred thousand years to about one billion years in the past, with periods more recent or earlier beyond its ability to reach.

- The further back in time the machine travels the less accurate it is; beyond the Triassic, it may arrive days or even months off schedule.

- The amount of time the machine spends in another era appears to equal in length to the amount of time that elapses in the present, in its absence.

- The timestream does not appear to allow paradox, defined as anything that might significantly alter events subsequent to the period visited. For instance, a person cannot travel to the same time twice. Attempting to do results in one being thrown back to the present, "torn to shreds in the process." The same would presumably result from attempting to interact with early humans. Therefore, the time machine is restricted from visiting the period of protohuman development, and refrains from visiting any time within one thousand years of a previous visit.

Species featured

editPrehistoric species of various eras featured in the series include Agriochoerus, Alamosaurus, Archaeotherium, Brontops, Camptosaurus, Columbian mammoth, Coryphodon, Deinosuchus, Diprotodon, Eurypterid, Gastornis (called Diatryma), Gorgosaurus, Hoplophoneus, Hyaenodon, Ichthyostega, Mastodon, Megalania, Merycoidodon, Metamynodon, Metoposaurus, Mylodon, Ornithomimus, Parasaurolophus, Phenacodus, Placerias, Postosuchus, Procoptodon, Rutiodon, Saurophaganax or Allosaurus (referred to as Epanterias), Stegosaurus, Teratosaurus, Triceratops, Troodon formosus (presented as Stenonychosaurus, and supposedly a type of pachycephalosaur), and Tyrannosaurus trionychus.

Tyrannosaurs of the genus Gorgosaurus are mentioned occasionally, and many times Reginald Rivers will say that the Raja is out in some period in the Cenozoic, taking a group to hunt some form of prehistoric mammal such as titanothere, entelodont, or uintathere. Prehistoric marsupials and Indricotherium are mentioned in "The Synthetic Barbarian," and numerous Pleistocene megafauna are seen in "The Mislaid Mastodon," including Castoroides ohioensis and the American lion.

Obsolete science

editWhile Rivers of Time is a well researched time travel series, paleontological knowledge has improved since the stories were written, rendering some aspects of its portrait of the prehistoric past obsolete. Dated material includes the following:

- Alamosaurus and other sauropods, portrayed as aquatic creatures forced to stay in the water much of the time, are now recognized as fully land-dwelling.

- Stenonychosaurus, portrayed as a pachycephalosaurid, is no longer recognized as a valid species, having been found to be identical to the Troodon, a raptor-like theropod.

- Gorgosaurus, portrayed as a type of carnosaur distinct from tyrannosaurs, is now included in the tyrannosaurid family.

- Tyrannosaurus and other fauna portrayed as living in the middle Cretaceous in fact appeared in the last five to seven million years of the period; the actual fauna of the middle Cretaceous included species such as Nothronychus, Pawpawsaurus, Protohadros, and Zuniceratops.

- The teratosaur of the late Triassic period is portrayed as a carnosaur; current thinking suggests that it and most other "carnosaurs" of the time were actually rauisuchians (with the exceptions of Liliensternus, Dilophosaurus, and their kin).

Sequel

editA tenth story of Reginald Rivers, "Gun, Not for Dinosaur", authored by Chris Bunch,[2] appeared in Harry Turtledove's 2005 tribute anthology honoring L. Sprague de Camp, The Enchanter Completed. This story contains elements of scientific racism and white supremacism as Rivers' client, a racist Texas millionaire, and his two Boer bodyguards attempt to prevent the evolution of Negroes by going back in time in Africa to kill their prehistoric ancestors.

Reception

editJanice M. Eisen, reviewing the work in Aboriginal Science Fiction, calls de Camp "one of the great old pros of the SF field. When reading him, you're always guaranteed a good time, and sometimes more." She gives the collection a three star rating, deeming it "lightweight, amusing work ... very well done candy, with a little paleontological education thrown in," and "particularly sharp shots at fundamentalists and animal-rights activists." But the stories, she feels, "are very old-fashioned;" often "merely vignettes, with action but little plot, and they all follow the same formulaic structure." She finds the characters "drawn with broad strokes on high-quality cardboard, [with] motivations ... at best shadowy. " She notes, however, that "de Camp's sense of humor never fails, and the tales are often witty." She judges them "best, and funniest, if they're not all read at one sitting."[4]

The collection was also reviewed by Gary K. Wolfe in Locus no. 95, Dec. 1993, and Don D'Ammassa in Science Fiction Chronicle no. 169, Jan. 1994.[1]

References

edit- ^ a b Rivers of Time title listing at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- ^ a b Reginald Rivers series listing at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- ^ Rivers of Time audiobook read by James Adams

- ^ Eisen, Janet. Review in Aboriginal Science Fiction v. 7, no. 4, Spring 1994, pages 53-54.