Linus Torvalds: Linux succeeded thanks to selfishness and trust

- Published

Linus Torvalds developed Linux in 1991 while at the University of Helsinki, Finland. He became a US citizen in 2010.

Linux creator Linus Torvalds has won the Millennium Technology Prize and an accompanying cheque for 600,000 euros ($756,000; £486,000) from the Technology Academy of Finland.

He was nominated for the award in recognition of the fact he had created the original Linux operating system and has continued to decide what modifications should be made to the Linux kernel - the code that lets software and hardware work together.

Today a variety of Linux-based systems power much of the world's computer servers, set-top boxes, smartphones, tablets, network routers, PCs and supercomputers.

<italic>Ahead of the announcement Mr Torvalds gave a rare interview to the BBC.</italic>

<bold>When you posted about the original system kernel on Usenet in 1991 what did you think would happen to it?</bold>

I think your question assumes a level of planning that simply didn't really exist. It wasn't so much about me having any particular expectations of what would happen when I made the original kernel sources available: a lot of the impetus for releasing it was simply a kind of "hey, look at what I've done".

I was definitely not expecting people to help me with the project, but I was hoping for some feedback about what I'd done, and looking for ideas of what else people would think was a good idea.

<bold>The success of Linux is in large part due to its open source nature. Why do you think people have been willing to give up so much time without financial reward?</bold>

In many ways, I actually think the real idea of open source is for it to allow everybody to be "selfish", not about trying to get everybody to contribute to some common good.

The Linux-based Android smartphone system has spread the use of Mr Torvalds' invention

In other words, I do not see open source as some big goody-goody "let's all sing kumbaya around the campfire and make the world a better place". No, open source only really works if everybody is contributing for their own selfish reasons.

Now, those selfish reasons by no means need to be about "financial reward", though.

The early "selfish" reasons to do Linux tended to be centred about just the pleasure of tinkering. That was why I did it - programming was my hobby - passion, really - and learning how to control the hardware was my own selfish goal. And it turned out that I was not all that alone in that.

Big universities with computer science departments had people who were interested in the same kinds of things.

And most people like that may not be crazy enough to start writing their own operating system from scratch, but there were certainly people around who found this kind of tinkering with hardware interesting, and who were interested enough to start playing around with the system and making suggestions on improvements, and eventually even making those improvements themselves and sending them back to me.

And the copyright protected those kinds of people. If you're a person who is interested in operating systems, and you see this project that does this, you don't want to get involved if you feel like your contributions would be somehow "taken advantage of", but with the GPLv2 [licence], that simply was never an issue.

The fundamental property of the GPLv2 is a very simple "tit-for-tat" model: I'll give you my improvements, if you promise to give your improvements back.

It's a fundamentally fair licence, and you don't have to worry about somebody else then coming along and taking advantage of your work.

And the thing that then seemed to surprise people, is that that notion of "fairness" actually scales very well.

Sure, a lot of companies were initially fairly leery about a licence that they weren't all that used to, and sometimes doubly so because some portions of the free software camp had been very vocally anti-commercial and expected companies to overnight turn everything into free software.

But really, the whole "tit-for-tat" model isn't just fair on an individual scale, it's fair on a company scale, and it's fair on a global scale.

Once people and companies got over their hang-ups - renaming it "open source" and just making it clear that this was not some kind of anti-commercial endeavour definitely helped - things just kind of exploded.

And the thing is, if your competition doesn't put in the same kind of effort that you do, then they can't reap the same kinds of rewards you can: if they don't contribute, they don't get to control the direction of the project, and they won't have the same kind of knowledge and understanding of it that you do.

Mr Torvalds has built up a collection of penguins - the official mascot of the Linux kernel

So there really are big advantages to being actively involved - you can't just coast along on somebody else's work.

<bold>7,800 developers across 80 countries contributed to the last version of the Linux kernel. But as it becomes more complex is there a danger it become less accessible for new people to get involved?</bold>

So the kernel has definitely grown more complex, and certain core areas in particular are things that a new developer should absolutely not expect to just come in and start messing around with.

People get very nervous when somebody they don't see as having a solid track record starts sending patches to core - and complex - code like the VM subsystem.

So it's absolutely much harder to become a core developer today than it was 15 years ago.

At the same time, I do think it's pretty easy to get into kernel development if you don't go for the most complex and central parts first. The fact that I do a kernel release roughly every three months, and each of those releases generally have over 1,000 people involved in it, says that we certainly aren't lacking for contributors.

<bold>You have previously mentioned that you can't check that all the code that gets submitted will work across all hardware - how big an issue is trust in an open source project like this?</bold>

Oh, trust is the most important thing. And it's a two-way street.

It's not just that I can trust some sub-lieutenant to do the right thing, it's that they in turn can trust me to be impartial and do the right thing.

We certainly don't always agree, and sometimes the arguments can get quite heated, but at the end of the day, you may not even always like each other, if you can at least trust that people aren't trying to screw you over.

And this trust issue is why I didn't want to ever work for a commercial Linux company, for example.

I simply do not want people to have even the appearance of bias - I want people to be able to trust that I'm impartial not only because they've seen me maintain the kernel over the years, but because they know that I simply don't have any incentives where I might want to support one Linux company over another.

These days, I do work full-time on Linux, and I'm paid to do it, but that didn't happen until I felt comfortable that there was a way that could be pretty obviously neutral, through a industry non-profit that doesn't really sell Linux itself.

And even then, in order to allay all fears, we actually made sure that my contract explicitly says that my employment does not mean that the Linux Foundation can tell me what to do.

So exactly because I think these kinds of trust issues are so important, I have one of the oddest employment contracts you've ever heard of.

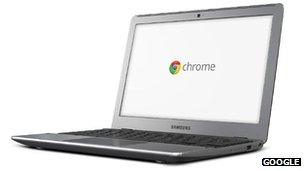

Google's Chromebook laptop comes preinstalled with its Linux-based system

It's basically one paragraph talking about what I'm supposed to do - it basically boils down to the fact that everything I do has to be open source - and the rest of the contract is about all the ways that the company I work for cannot influence me.

"Trust" is not about some kind of absolute neutrality, or anything like that, but it's about a certain level of predictability and about knowing that you won't be shafted.

<bold>Linux is popular in many areas of computing including smartphones and servers, but it has never had quite the same breakthrough on desktops - do you think it will ever happen?</bold>

So I think that in order to make it in a consumer market, you really do need to be pre-installed. And as Android has shown, Linux really can be very much a consumer product. So it's not that the consumer market itself would necessarily be a fundamentally hard nut to crack, but the "you need to come preinstalled" thing is a big thing.

And on the laptop and desktop market, we just haven't ever had any company making that kind of play. And don't get me wrong - it's not an easy play to make.

That said, I wouldn't dismiss it either. The whole "ubiquitous web browser" thing has made that kind of consumer play be more realistic, and I think that Google's Chrome push (Chromebox and Chromebooks) is clearly aiming towards that.

So I'm still hopeful. For me, Linux on the desktop is where I started, and Linux on the desktop is literally what I still use today primarily - although I obviously do have other Linux devices, including an Android phone - so I'd personally really love for it to take over in that market too.

But I guess that in the meantime I can't really complain about the successes in other markets.

The budget-priced Raspberry Pi can run off an SD card loaded with a Linux operating system

<bold>Steve Ballmer once described Linux as a "cancer", but in recent months we've heard that Microsoft is running its Skype division off Linux boxes, and it's now offering a Linux-based version of its Azure cloud service - does this give you satisfaction?</bold>

Well, let's say that I'm relieved that Microsoft seems to have at least to some degree stopped seeing Linux as the enemy. The whole "cancer" and "un-American" thing was really pretty embarrassing.

<bold>The recent launch of the Raspberry Pi, running on Linux, has attracted a lot of attention. Are you hopeful it will inspire another generation of programmers who can contribute to the Linux kernel?</bold>

So I personally come from a "tinkering with computers" background, and yes, as a result I find things like Raspberry Pi to be an important thing: trying to make it possible for a wider group of people to tinker with computers and just playing around.

And making the computers cheap enough that you really can not only afford the hardware at a big scale, but perhaps more important, also "afford failure".

By that I mean that I suspect a lot of them will go to kids who play with them a bit, but then decide that they just can't care.

But that's OK. If it's cheap enough, you can afford to have a lot of "don't cares" if then every once in a while you end up triggering even a fairly rare "do care" case.

So I actually think that if you make these kinds of platforms cheap enough - really "throw-away cheap" in a sense - the fact that you can be wasteful can be a good thing, if it means that you will reach a few kids you wouldn't otherwise have reached.

<bold>You work from home - how hard is it to avoid being distracted by family life and focusing on what must be very abstract concepts?</bold>

Oh, I'm sure it can be hard for some people. It's never been a problem for me.

Mr Torvalds works on the Linux kernel in his office at home in Oregon

I've always tended to find computers fascinating, often to the point where I just go off and do my own thing and am not very social.

Having a family doesn't seem to have made that character trait really any different.

I'll happily sit in front of the computer the whole day, and if the kids distract me when I'm in the middle of something, a certain amount of cursing might happen.

In other words: what could be seen as a socially debilitating failure of character can certainly work to your advantage too.

- Published20 April 2012