Usuari:Jaumellecha/proves3: diferència entre les revisions

m Eliminat tot el contingut de la pàgina Etiquetes: Buidament Reversió manual edició visual: canviat |

mCap resum de modificació Etiqueta: Revertida |

||

| Línia 1: | Línia 1: | ||

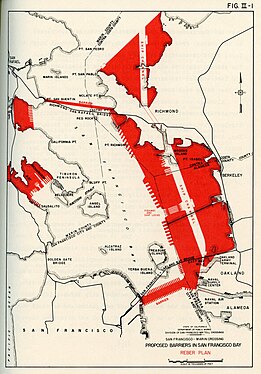

6- The '''Reber Plan''' was a late 1940s plan to fill in parts of the [[San Francisco Bay]]. It was designed and advocated by John Reber—an actor, theatrical producer, and schoolteacher.{{sfn|Moffitt|2021}} |

|||

== Projecte «Badia de San Francisco» == |

|||

5- Under the plan, which was also known as the ''«San Francisco Bay Project»'', the mouth of the [[Sacramento River]] (from [[Suisun Bay]]) would be channelized by dams and would feed two vast freshwater lakes within the bay, providing drinking and irrigation water to the residents and farmers of the [[San Francisco Bay area|Bay Area]]. The barriers would support rail and highway traffic and would create the two freshwater lakes. Between the lakes, Reber proposed the reclamation of {{convert|20000|acre|km2|0}} of land that would be crossed by a freshwater channel. West of the channel would be airports, a naval base, and a pair of locks comparable in size to those of the Panama Canal. Industrial plants would be developed on the east.<ref>{{ref-web|url=http://www.lib.berkeley.edu/news_events/bridge/unbuilt_2.html |títol=Bridging the Bay, Bridging the Campus: Salt Water Barriers |obra=[[University of California, Berkeley|UC Berkeley]] Library|llengua=anglès}}</ref> |

|||

<gallery mode="packed" heights="250"> |

|||

Fitxer:Reber Plan.jpg|Proposed barriers in the San Francisco Bay |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

4- The ''[[San Francisco Chronicle]]'' endorsed the plan's concept of a [[causeway]] to replace or supplement the [[San Francisco Bay Bridge]], stating:<ref>{{ref-publicació|article=Causeway to the Future|publicació=[[The San Francisco Chronicle]]|data=17 d'agost de 1946 |llengua=anglès}}</ref> |

|||

{{cita|''There are a great many difficulties to be surmounted, just as there were for the Bay and Golden Gate bridges, but they can be surmounted by application of the same kind of drive and technical know-how that brought the present great spans into being.''}} |

|||

==Feasibility tested== |

|||

3- In 1946, the Alameda County Committee for a Second Bay Crossing and noted civil engineer [[Glenn B. Woodruff]] estimated the plan would cost $2.5 billion, more than 10 times Reber's estimate. Woodruff, who had helped design the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge, blamed a misunderstanding of the geology of the bay for the massive discrepancy.{{sfn|Hope|1946|p=1-2}} |

|||

2- In 1953 the [[U.S. Army Corps of Engineers]] recommended more detailed study of the plan and eventually constructed [[U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Bay Model|a hydraulic model of the Bay Area]] to test it. The barriers, which were the plan's essential element, failed to survive this critical study.<ref>{{ref-web|url=https://boomcalifornia.com/2015/04/14/the-man-who-helped-save-san-francisco-bay-by-trying-to-destroy-it/ |títol = The Man Who Helped Save the Bay by Trying to Destroy It |obra=Boom California |data = 15 d'abril de 2015 |llengua=anglès}}</ref><ref>{{ref-publicació |publicació=California State Assembly |article=First Report of the Interim Fact-Finding Committee on Tideland Reclamation and Development in Northern California, Related to Traffic Problem and Relief of Congestion on Transbay Crossings |lloc=Sacramento |any= 1949 |pàgina= 23-25, 27 |llengua=anglès}}</ref>{{sfn|Savage|1951|p=1-2, 24-78}}{{sfn|Jackson|Paterson|1977|p=63-65}} |

|||

1- The scrapping of the Reber Plan in the early 1960s was one sign, perhaps, of the end of an era of grandiose civil works projects aimed at totally restructuring a region's natural environment, and the birth of the environmental era.<ref>{{ref-publicació |url=https://psmag.com/environment/the-fitness-of-physical-models-38084 |data=5 de desembre de 2011 |article=The Fitness of Physical Models |publicació=Pacific Standard Magazine |llengua=anglès</ref> |

|||

== Referències == |

|||

{{referències}} |

|||

== Bibliografia == |

|||

{{Div col|cols=2}} |

|||

* {{ref-publicació |cognom=Hope |nom=Dave |mes=agost |any=1946 |article=Board hears Objections to Crossing Plan |publicació=Oakland Tribune |llengua=anglès}} |

|||

* {{ref-llibre |nom=W. Turrentine |cognom= Jackson |nom2=Alan M. |cognom2=Paterson |títol=The Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta: The Evolution and Implementation of Water Policy |editorial=California Water Resources Center |any=1977 |llengua=anglès}} |

|||

* {{ref-publicació | url=https://www.sfgate.com/local/article/second-bay-bridge-plans-history-freeway-alameda-sf-14018498.php#taboola-5 |article=The spectacularly doomed plan to fill the San Francisco bay with a 36-lane freeway |cognom=Moffitt |nom=Mike |publicació=[[San Francisco Chronicle]] |mes=abril |any=2021 |llengua=anglès}} |

|||

* {{ref-llibre |nom=John L. |cognom=Savage |títol=Report on Development of the San Francisco Bay Region |lloc=San Francisco |any=1951 |llengua=anglès}} |

|||

{{Div col end}} |

|||

{{autoritat}} |

|||

[[Categoria:San Francisco]] |

|||

Revisió del 02:40, 1 feb 2024

6- The Reber Plan was a late 1940s plan to fill in parts of the San Francisco Bay. It was designed and advocated by John Reber—an actor, theatrical producer, and schoolteacher.[1]

Projecte «Badia de San Francisco»

5- Under the plan, which was also known as the «San Francisco Bay Project», the mouth of the Sacramento River (from Suisun Bay) would be channelized by dams and would feed two vast freshwater lakes within the bay, providing drinking and irrigation water to the residents and farmers of the Bay Area. The barriers would support rail and highway traffic and would create the two freshwater lakes. Between the lakes, Reber proposed the reclamation of 20,000 acres (81 km2) of land that would be crossed by a freshwater channel. West of the channel would be airports, a naval base, and a pair of locks comparable in size to those of the Panama Canal. Industrial plants would be developed on the east.[2]

-

Proposed barriers in the San Francisco Bay

4- The San Francisco Chronicle endorsed the plan's concept of a causeway to replace or supplement the San Francisco Bay Bridge, stating:[3]

| « | There are a great many difficulties to be surmounted, just as there were for the Bay and Golden Gate bridges, but they can be surmounted by application of the same kind of drive and technical know-how that brought the present great spans into being. | » |

Feasibility tested

3- In 1946, the Alameda County Committee for a Second Bay Crossing and noted civil engineer Glenn B. Woodruff estimated the plan would cost $2.5 billion, more than 10 times Reber's estimate. Woodruff, who had helped design the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge, blamed a misunderstanding of the geology of the bay for the massive discrepancy.[4]

2- In 1953 the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers recommended more detailed study of the plan and eventually constructed a hydraulic model of the Bay Area to test it. The barriers, which were the plan's essential element, failed to survive this critical study.[5][6][7][8] 1- The scrapping of the Reber Plan in the early 1960s was one sign, perhaps, of the end of an era of grandiose civil works projects aimed at totally restructuring a region's natural environment, and the birth of the environmental era.[9]

Referències

- ↑ Moffitt, 2021.

- ↑ «Bridging the Bay, Bridging the Campus: Salt Water Barriers» (en anglès). UC Berkeley Library.

- ↑ «Causeway to the Future» (en anglès). The San Francisco Chronicle, 17-08-1946.

- ↑ Hope, 1946, p. 1-2.

- ↑ «The Man Who Helped Save the Bay by Trying to Destroy It» (en anglès). Boom California, 15-04-2015.

- ↑ «First Report of the Interim Fact-Finding Committee on Tideland Reclamation and Development in Northern California, Related to Traffic Problem and Relief of Congestion on Transbay Crossings» (en anglès). California State Assembly [Sacramento], 1949, pàg. 23-25, 27.

- ↑ Savage, 1951, p. 1-2, 24-78.

- ↑ Jackson i Paterson, 1977, p. 63-65.

- ↑ {{ref-publicació |url=https://psmag.com/environment/the-fitness-of-physical-models-38084 |data=5 de desembre de 2011 |article=The Fitness of Physical Models |publicació=Pacific Standard Magazine |llengua=anglès

Bibliografia

- Hope, Dave «Board hears Objections to Crossing Plan» (en anglès). Oakland Tribune, agost 1946.

- Jackson, W. Turrentine; Paterson, Alan M. The Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta: The Evolution and Implementation of Water Policy (en anglès). California Water Resources Center, 1977.

- Moffitt, Mike «The spectacularly doomed plan to fill the San Francisco bay with a 36-lane freeway» (en anglès). San Francisco Chronicle, abril 2021.

- Savage, John L. Report on Development of the San Francisco Bay Region (en anglès), 1951.