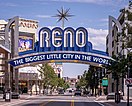

Reno (/ˈriːnoʊ/ REE-noh) is a city in the northwest section of the U.S. state of Nevada, along the Nevada–California border. It is the county seat and most populous city of Washoe County. Sitting in the High Eastern Sierra foothills, in the Truckee River valley, on the eastern side of the Sierra Nevada, it is about 23 miles (37 km) northeast of Lake Tahoe. Known as "The Biggest Little City in the World",[4] it is the 80th most populous city in the United States, the 3rd most populous city in Nevada, and the most populous in Nevada outside the Las Vegas Valley. The city had a population of 264,165 at the 2020 census.[3]

Reno, Nevada | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Nickname: "The Biggest Little City in the World" | |

| Coordinates: 39°31′38″N 119°49′19″W / 39.52722°N 119.82194°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Nevada |

| County | Washoe |

| Founded | May 9, 1868 |

| Incorporated | March 16, 1903 |

| Named for | Jesse L. Reno |

| Government | |

| • Type | Council–manager |

| • Mayor | Hillary Schieve (I) |

| • Vice Mayor | Devon Reese |

| • City Council | Members

|

| • City manager | Jackie Bryant (interim) |

| Area | |

• City | 111.70 sq mi (289.30 km2) |

| • Land | 108.86 sq mi (281.96 km2) |

| • Water | 2.83 sq mi (7.34 km2) |

| Elevation | 4,505 ft (1,373 m) |

| Population | |

• City | 264,165 |

| • Rank | 80th in the United States 3rd in Nevada |

| • Density | 2,426.54/sq mi (936.89/km2) |

| • Urban | 446,529 (US: 91st) |

| • Urban density | 2,699.2/sq mi (1,042.2/km2) |

| • Metro | 490,596 (US: 114th) |

| Demonym | Renoites |

| Time zone | UTC−08:00 (PST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−07:00 (PDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 89501-89513, 89515, 89519-89521, 89523, 89533, 89555, 89557, 89570, 89595, 89599 |

| Area code | 775 |

| FIPS code | 32-60600 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0861100[2] |

| Website | www |

| Reference no. | 30 |

The city is named after Civil War Union Major General Jesse L. Reno, who was killed in action during the American Civil War at the Battle of South Mountain, on Fox's Gap.

Reno is part of the Reno–Sparks metropolitan area, the second-most populous metropolitan area in Nevada after the Las Vegas Valley.[5] Known as Greater Reno, it includes Washoe, Storey, and Lyon Counties; the independent city and state capital Carson City; and parts of Placer and Nevada Counties in California.[6] The Reno metro area (along with the neighboring city Sparks) occupies a valley colloquially known as the Truckee Meadows.

For much of the twentieth century Reno saw a significant number of migrants seeking to take advantage of Nevada's relatively lax divorce laws and the city gained a national reputation as a divorce mill. Today Reno is a tourist destination known for its casino gambling and proximity to Lake Tahoe and the Sierra Nevada Mountains.

History

editEarly history

editArchaeological finds place the eastern border for the prehistoric Martis people in the Reno area.[7] As early as the mid-1850s, a few pioneers settled in the Truckee Meadows, a relatively fertile valley through which the Truckee River made its way from Lake Tahoe to Pyramid Lake. In addition to subsistence farming, these early residents could pick up business from travelers along the California Trail, which followed the Truckee westward, before branching off towards Donner Lake, where the formidable obstacle of the Sierra Nevada began.

Gold was discovered in the vicinity of Virginia City in 1850, and a modest mining community developed, but the discovery of silver in 1859 at the Comstock Lode led to a mining rush, and thousands of emigrants left their homes, bound for the West, hoping to find a fortune.

To provide the necessary connection between Virginia City and the California Trail, Charles W. Fuller built a log toll bridge across the Truckee River in 1859. A small community that served travelers soon grew near the bridge.[8] After two years, Fuller sold the bridge to Myron C. Lake, who continued to develop the community by adding a grist mill, kiln, and livery stable to the hotel and eating house. He renamed it "Lake's Crossing". Most of what is present-day western Nevada was formed as the Nevada Territory from part of Utah Territory in 1861.

By January 1863, the Central Pacific Railroad (CPRR) had begun laying tracks east from Sacramento, California, eventually connecting with the Union Pacific Railroad at Promontory, Utah, to form the First transcontinental railroad. Lake deeded land to the CPRR in exchange for its promise to build a depot at Lake's Crossing. In 1864, Washoe County was consolidated with Roop County, and Lake's Crossing became the county's largest town. Lake had earned himself the title "founder of Reno".[9] Once the railroad station was established, the town of Reno officially came into being on May 9, 1868.[10] CPRR construction superintendent Charles Crocker named the community after Major General Jesse Lee Reno, a Union officer killed in the Civil War at the Battle of South Mountain.

In 1871, Reno became the county seat of the newly expanded Washoe County, replacing the county seat in Washoe City. However, political power in Nevada remained with the mining communities, first Virginia City and later Tonopah and Goldfield.[11][12]

The extension of the Virginia and Truckee Railroad to Reno in 1872 provided a boost to the new city's economy. In the following decades, Reno continued to grow and prosper as a business and agricultural center and became the principal settlement on the transcontinental railroad between Sacramento and Salt Lake City.[13] As the mining boom waned early in the 20th century, Nevada's centers of political and business activity shifted to the nonmining communities, especially Reno and Las Vegas. Nevada is still the third-largest gold producer in the world, after South Africa and Australia; the state yielded 6.9% of the world's supply in 2005 world gold production.[14]

The Reno Arch was erected on Virginia Street in 1926 to promote the upcoming Transcontinental Highways Exposition of 1927. The arch included the words "Nevada's Transcontinental Highways Exposition" and the dates of the exposition. After the exposition, the Reno City Council decided to keep the arch as a permanent downtown gateway, and Mayor E.E. Roberts asked the citizens of Reno to suggest a slogan for the arch. No acceptable slogan was received until a $100 prize was offered, and G.A. Burns of Sacramento was declared the winner on March 14, 1929, with "Reno, the Biggest Little City in the World".[15]

The divorce capital of the world

editIn the early twentieth century Nevada became a popular destination for migratory divorce in an era when most states had highly restrictive laws on the subject. Legislation passed in 1931 completed the gradual reduction of residency requirement from six months to six weeks, and Reno openly advertised itself as the "Divorce Capital of the World". Nevada's laws, which were fairly progressive for the time, allowed numerous grounds for divorce and Reno's courts quickly gained a reputation for handling cases with both celerity and sympathy for those seeking to "untie the knot". From the 1930s through the 1960s Reno became synonymous with speedy divorce, often referred to colloquially as "the six week cure". During these decades the city's reputation drew thousands of divorcees annually, and they in turn became an important part of the local economy. These temporary residents flocked to hotels, boardinghouses, and hospitality ranches, many of which catered primarily to those waiting out the six week residency requirement before their court date.[16] Numerous local businesses openly courted these visitors, such as R. Herz & Bro, a jewelry store that offered ring resetting services to the recently divorced and the luxurious El Cortez Hotel, which was built in part to accommodate the more affluent among Reno's six week guests.[17][18] The majority of those who came to Reno for divorce were women as Nevada did not require both parties in a divorce case to be present in court, and men often could not take that much time off from work. Although new "residents" seeking divorce were required to swear under oath that they intended to make Nevada their permanent home, most left soon after obtaining their divorce decree, which often occurred on the same day as the initial court hearing.[16]

In addition to tens of thousands of ordinary people, Reno also became a major destination for celebrities, and the very wealthy looking to end their marriages as quickly as possible. Some of the many famous personages who got divorced in Reno include Mary Pickford, Jack Dempsey, General Douglas MacArthur, Carol Lombard, Tallulah Bankhead, Adlai Stevenson II, Lana Turner, Nelson Rockefeller, Georges Simenon, Rita Hayworth, Gloria Vanderbilt and Cornelius Vanderbilt IV. The latter was married seven times and had five of his six divorces in Nevada. Mr. Vanderbilt was so taken with Reno that, unlike most migrant divorcees, he eventually settled there permanently.[19][20]

In the 1939 film The Women, Reno and its divorce culture serve as a backdrop to a significant part of the plot. Ernie Pyle once wrote in one of his columns, "All the people you saw on the streets in Reno were obviously there to get divorces." In Ayn Rand's novel The Fountainhead, published in 1943, the New York-based female protagonist tells a friend, "I am going to Reno," which was understood as declaring their intention to get a divorce.[21]

The divorce business eventually died out during the 1970s, as other states began relaxing their laws, and especially with the widespread introduction of no fault divorce.[16]

Gambling and modern Reno

editReno took a leap forward when the state of Nevada legalized open gambling on March 19, 1931, at the same time as it liberalized its divorce laws. The statewide push for legal Nevada gaming was led by Reno entrepreneur Bill Graham, who owned the Bank Club Casino in Reno, which was on Center Street. No other state offered legalized casino gaming like Nevada had in the 1930s, and casinos such as the Bank Club and Palace were popular.[22] A few states had legal parimutuel horse racing, but no other state had legal casino gambling.

Within a few years, the Bank Club, owned by George Wingfield, Bill Graham, and Jim McKay, was the state's largest employer and the largest casino in the world. Wingfield owned most of the buildings in town that housed gaming and took a percentage of the profits, along with his rent.[23]

As the divorce industry declined, gambling became the major Reno industry. While gaming pioneers such as "Pappy" and Harold Smith of Harold's Club and Bill Harrah of the soon-to-dominate Harrah's Casino set up shop in the 1930s, the war years of the 1940s cemented Reno as the place to play for two decades.[24] Beginning in the 1950s, the need for economic diversification beyond gaming fueled a movement for more lenient business taxation.[21]

At 1:03 pm, on February 5, 1957, two explosions, caused by natural gas leaking into the maze of pipes and ditches under the city, and an ensuing fire, destroyed five buildings in the vicinity of Sierra and First Streets along the Truckee River. The disaster killed two people and injured 49. The first explosion hit under the block of shops on the west side of Sierra Street (now the site of the Century Riverside), the second, across Sierra Street, now the site of the Palladio.[25]

The presence of a main east–west rail line, the emerging interstate highway system, favorable state tax climate, and relatively inexpensive land created good conditions for warehousing and distribution of goods.[26]

In the 1980s, Indian gaming rules were relaxed, and starting in 2000, Californian Native casinos began to cut into Reno casino revenues.[27] Major new construction projects have been completed in the Reno and Sparks areas. A few new luxury communities were built in Truckee, California, about 28 miles (45 km) west of Reno on Interstate 80. Reno also is an outdoor recreation destination, due to its proximity to the Sierra Nevada, Lake Tahoe, and numerous ski resorts in the region.[28]

In 2018, the city officially changed its flag after a local contest was held.[29] In recent years, the Reno metro area − spurred by large-scale investments from Greater Seattle and San Francisco Bay Area companies such as Amazon, Tesla, Panasonic, Microsoft, Apple, and Google − has become a new major technology center in the United States.[30]

Geography

editGeology

editReno is just east of the Sierra Nevada, on the western edge of the Great Basin at an elevation of about 4,400 feet (1,300 m) above sea level. Numerous faults exist throughout the region. Most of these are normal (vertical motion) faults associated with the uplift of the various mountain ranges, including the Sierra Nevada.

In February 2008, an earthquake swarm began to occur, lasting for several months, with the largest quake registering at 4.9 on the Richter magnitude scale, although some geologic estimates put it at 5.0. The earthquakes were centered on the Somersett community in western Reno near Mogul and Verdi. Many homes in these areas were damaged.[31]

The unique high desert geological features cause many to "describe Nevada as a rockhound's paradise .... access to millions of acres of government land" allows geologists, miners, and amateur rockhounds in Nevada "to hunt to your heart's content .... being able to find agate, opal, jasper, fossils, fluorescent minerals, obsidian, chalcedony, wonderstone, malachite, petrified wood, limb casts, and much more means paradise."[32]

Environmental considerations

editThe Reno area is often subject to wildfires that cause property damage and sometimes loss of life. In August 1960, the Donner Ridge fire resulted in a loss of electricity to the city for four days.[33] In November 2011, arcing from powerlines caused a fire in Caughlin in southwest Reno that destroyed 26 homes and killed one man. Just two months later, a fire in Washoe Drive sparked by fireplace ashes destroyed 29 homes and killed one woman. Around 10,000 residents were evacuated, and a state of emergency was declared. The fires came at the end of Reno's longest recorded dry spell.[34] Wetlands are an important part of the Reno/Tahoe area. They act as a natural filter for the solids that come out of the water treatment plant. Plant roots absorb nutrients from the water and naturally filter it. Wetlands are home to over 75% of the species in the Great Basin. The area's wetlands are at risk of being destroyed due to development around the city. While developers build on top of the wetlands they fill them with soil, destroying the habitat they create for the plants and animals. Washoe County has devised a plan that will help protect these ecosystems: mitigation. In the future, when developers try to build over a wetland, they will be responsible for creating another wetland near Washoe Lake.[citation needed]

Climate

editReno has a cold semi-arid climate (Köppen: BSk), bordering a hot-summer Mediterranean climate (Köppen: Csa) to the west. It experiences moderately cold winters and hot summers; it is influenced by the Sierra Nevada mountains to the west and the more arid Great Basin to the east.[35] It is situated across a varied geographic landscape, which extends from the foothills of the Sierra Nevada into the Truckee River valley. While Reno experiences a rain shadow effect from the surrounding mountains, its western portions can receive three to four times as much precipitation as those extending eastward.[36] Annual rainfall patterns in Reno adhere to a Mediterranean climate, with most precipitation occurring in fall, winter, and spring, followed by long, hot, dry summers.[36] However, Reno's average annual rainfall is slightly lower than that of Californian cities more typically associated with Mediterranean climates. The area's low evapotranspiration stemming from its moderate annual average temperature also bears similarity to semi-arid climates found in Nevada's Great Basin.[37]

The monthly daily average temperature ranges from 36.2 °F (2.3 °C) in December to 77.2 °F (25.1 °C) in July, with the diurnal temperature variation occasionally reaching 40 °F (22 °C) in summer, still lower than much of the high desert to the east. There are 6.0 days of 100 °F (38 °C)+ highs, 65 days of 90 °F (32 °C)+ highs, 1.6 days with 70 °F (21 °C)+ lows, and 1.9 days with sub-10 °F (−12 °C) lows annually; the temperature reaches or dips below the freezing point on 122 days, and does not rise above freezing on only 4.1 of those days.[38] The all-time record high temperature is 108 °F (42 °C), which occurred on July 10 and 11, 2002, again on July 5, 2007, and again on July 16, 2023. The all-time record low temperature is −17 °F (−27 °C), which occurred on January 21, 1916; the lowest temperature recorded at the airport is −16 °F (−27 °C), which occurred on four occasions, most recently on February 7, 1989.[38] In addition, the region is windy throughout the year; observers such as Mark Twain have commented about the "Washoe Zephyr", northwestern Nevada's distinctive wind.

Annual precipitation has ranged from 1.55 inches (39.4 mm) in 1947 to 13.73 inches (348.7 mm) in 2017. The most precipitation in one month was 6.76 inches (171.7 mm) in January 1916 and the most precipitation in 24 hours was 2.71 inches (68.8 mm) on January 28, 1903. At Reno–Tahoe International Airport, where records go back to 1937, the most precipitation in one month was 5.57 inches (141.5 mm) in January 2017 and the most precipitation in 24 hours was 2.29 inches (58.2 mm) on January 21, 1943.[38]

Most rainfall occurs in winter and spring. Summer thunderstorms can occur between April and October. The eastern side of town and the mountains east of Reno tend to be prone to thunderstorms more often, and these storms may be severe because an afternoon downslope west wind, called a "Washoe Zephyr", can develop in the Sierra Nevada, causing air to be pulled down in the Sierra Nevada and Reno, destroying or preventing thunderstorms, but the same wind can push air upward against the Virginia Range and other mountain ranges east of Reno, creating powerful thunderstorms.[39][40]

Winter snowfall is usually light to moderate, but can be heavy some days, averaging 20.9 inches (53 cm) annually. Snowfall varies with the lowest amounts (roughly 19–23 inches annually) at the lowest part of the valley at and east of the airport at 4,404 feet (1,342 m), while the foothills of the Carson Range to the west ranging from 4,700 to 5,600 feet (1,400 to 1,700 m) in elevation just a few miles west of downtown can receive two to three times as much annual snowfall. The mountains of the Virginia Range to the east, meanwhile, can receive more summer thunderstorms and precipitation, and around twice as much annual snowfall above 5,500 feet (1,700 m). However, snowfall increases in the Virginia Range are less dramatic as elevation climbs than in the Carson Range to the west, because the Virginia Range is well within the rain shadow of the Sierra Nevada and Carson Range. The most snowfall in Reno in one winter was 72.3 inches (184 cm) in 1915–1916, with an astonishing 65.7 inches (167 cm) in January, the most in a calendar month, as well as 22.5 inches (57 cm) on January 17, the most in a calendar day; the most snowfall in a calendar year was 82.3 inches (209 cm) in 1916.[38]

| Climate data for Reno (RNO), 1991–2020 normals,[a] extremes 1893–present[b] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 71 (22) |

75 (24) |

83 (28) |

90 (32) |

98 (37) |

104 (40) |

108 (42) |

105 (41) |

106 (41) |

93 (34) |

77 (25) |

71 (22) |

108 (42) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 61.2 (16.2) |

65.3 (18.5) |

73.9 (23.3) |

80.9 (27.2) |

89.4 (31.9) |

97.0 (36.1) |

102.1 (38.9) |

100.0 (37.8) |

94.5 (34.7) |

85.0 (29.4) |

71.5 (21.9) |

61.7 (16.5) |

102.6 (39.2) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 46.7 (8.2) |

51.5 (10.8) |

58.2 (14.6) |

64.7 (18.2) |

74.1 (23.4) |

84.6 (29.2) |

93.4 (34.1) |

91.3 (32.9) |

82.8 (28.2) |

69.8 (21.0) |

55.7 (13.2) |

45.9 (7.7) |

68.2 (20.1) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 35.8 (2.1) |

39.6 (4.2) |

45.4 (7.4) |

51.0 (10.6) |

59.8 (15.4) |

68.8 (20.4) |

76.6 (24.8) |

74.3 (23.5) |

65.9 (18.8) |

54.8 (12.7) |

42.7 (5.9) |

35.1 (1.7) |

54.2 (12.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 24.9 (−3.9) |

27.5 (−2.5) |

32.7 (0.4) |

37.3 (2.9) |

45.6 (7.6) |

53.0 (11.7) |

59.8 (15.4) |

57.3 (14.1) |

49.0 (9.4) |

38.7 (3.7) |

29.8 (−1.2) |

24.2 (−4.3) |

40.0 (4.4) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 12.2 (−11.0) |

15.1 (−9.4) |

21.3 (−5.9) |

26.2 (−3.2) |

34.0 (1.1) |

41.0 (5.0) |

50.7 (10.4) |

48.5 (9.2) |

39.0 (3.9) |

27.4 (−2.6) |

17.4 (−8.1) |

11.3 (−11.5) |

5.6 (−14.7) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −17 (−27) |

−19 (−28) |

−3 (−19) |

13 (−11) |

16 (−9) |

25 (−4) |

33 (1) |

24 (−4) |

20 (−7) |

8 (−13) |

1 (−17) |

−16 (−27) |

−19 (−28) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 1.25 (32) |

1.03 (26) |

0.80 (20) |

0.44 (11) |

0.55 (14) |

0.41 (10) |

0.20 (5.1) |

0.24 (6.1) |

0.21 (5.3) |

0.50 (13) |

0.62 (16) |

1.10 (28) |

7.35 (187) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 5.2 (13) |

5.2 (13) |

2.9 (7.4) |

0.4 (1.0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

1.8 (4.6) |

5.2 (13) |

20.9 (53) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 6.9 | 7.0 | 5.5 | 4.5 | 4.4 | 3.1 | 1.7 | 1.6 | 2.0 | 2.9 | 4.3 | 6.6 | 50.5 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 3.4 | 3.3 | 2.0 | 0.7 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 1.2 | 3.0 | 13.9 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 68.0 | 60.2 | 52.7 | 45.9 | 43.2 | 39.9 | 36.2 | 39.3 | 44.0 | 50.7 | 61.2 | 67.6 | 50.7 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 21.2 (−6.0) |

23.0 (−5.0) |

23.5 (−4.7) |

25.3 (−3.7) |

31.5 (−0.3) |

36.5 (2.5) |

39.6 (4.2) |

39.4 (4.1) |

34.9 (1.6) |

29.5 (−1.4) |

25.3 (−3.7) |

21.0 (−6.1) |

29.2 (−1.5) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 195.6 | 204.2 | 291.0 | 332.1 | 375.8 | 393.8 | 424.0 | 390.8 | 343.9 | 295.2 | 212.0 | 187.5 | 3,645.9 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 65 | 68 | 78 | 83 | 84 | 88 | 93 | 92 | 92 | 85 | 70 | 64 | 82 |

| Source: NOAA (relative humidity, dew points and sun 1961–1990)[41][42][43] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Stead, 1991–2020 normals[c] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 43.4 (6.3) |

47.2 (8.4) |

53.9 (12.2) |

59.5 (15.3) |

69.0 (20.6) |

79.2 (26.2) |

88.8 (31.6) |

87.1 (30.6) |

79.4 (26.3) |

66.3 (19.1) |

52.4 (11.3) |

43.1 (6.2) |

64.1 (17.8) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 33.6 (0.9) |

36.8 (2.7) |

42.3 (5.7) |

47.1 (8.4) |

55.6 (13.1) |

64.1 (17.8) |

72.8 (22.7) |

70.8 (21.6) |

63.5 (17.5) |

51.8 (11.0) |

40.5 (4.7) |

33.4 (0.8) |

51.0 (10.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 23.9 (−4.5) |

26.4 (−3.1) |

30.6 (−0.8) |

34.7 (1.5) |

42.2 (5.7) |

49.0 (9.4) |

56.9 (13.8) |

54.6 (12.6) |

47.6 (8.7) |

37.2 (2.9) |

28.5 (−1.9) |

23.7 (−4.6) |

37.9 (3.3) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 1.59 (40) |

1.55 (39) |

1.24 (31) |

0.48 (12) |

0.59 (15) |

0.51 (13) |

0.39 (9.9) |

0.19 (4.8) |

0.32 (8.1) |

0.76 (19) |

1.15 (29) |

2.20 (56) |

10.97 (276.8) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 4.0 (10) |

3.1 (7.9) |

2.5 (6.4) |

0.6 (1.5) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

1.0 (2.5) |

5.4 (14) |

16.7 (42.55) |

| Source: NOAA[44] | |||||||||||||

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. There is more info on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

See or edit raw graph data.

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1860 | 1,035 | — | |

| 1870 | 1,035 | 0.0% | |

| 1880 | 1,362 | 31.6% | |

| 1890 | 3,563 | 161.6% | |

| 1900 | 4,500 | 26.3% | |

| 1910 | 10,867 | 141.5% | |

| 1920 | 12,016 | 10.6% | |

| 1930 | 18,529 | 54.2% | |

| 1940 | 21,317 | 15.0% | |

| 1950 | 32,497 | 52.4% | |

| 1960 | 51,470 | 58.4% | |

| 1970 | 72,863 | 41.6% | |

| 1980 | 100,756 | 38.3% | |

| 1990 | 133,850 | 32.8% | |

| 2000 | 197,177 | [citation needed] | 47.3% |

| 2010 | 236,728 | [citation needed] | 20.1% |

| 2020 | 264,165 | [3] | 11.6% |

| [45] | |||

2020 census

editThis section needs expansion with: examples with reliable citations. You can help by adding to it. (September 2021) |

| Race / Ethnicity(NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 2000[46] | Pop 2010[47] | Pop 2020[48] | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 124,870 | 140,752 | 152,015 | 69.19% | 62.50% | 57.55% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 4,414 | 5,990 | 7,575 | 2.45% | 2.66% | 2.87% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 1,772 | 2,066 | 1,881 | 0.98% | 0.92% | 0.71% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 9,423 | 13,913 | 18,344 | 5.22% | 6.18% | 6.94% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 971 | 1,505 | 1,917 | 0.54% | 0.67% | 0.73% |

| Other race alone (NH) | 250 | 441 | 1,389 | 0.14% | 0.20% | 0.53% |

| Mixed race or Multiracial (NH) | 4,164 | 5,914 | 14,064 | 2.31% | 2.63% | 5.32% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 34,616 | 54,640 | 66,980 | 19.18% | 24.26% | 25.36% |

| Total | 180,480 | 225,221 | 264,165 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

As of the census of 2010, there were 225,221 people, 90,924 households, and 51,112 families residing in the city. The population density was 2,186.6 inhabitants per square mile (844.3/km2). There were 102,582 housing units at an average density of 995.9 per square mile (384.5/km2). The city's racial makeup was 74.2% White, 2.9% African American, 1.3% Native American, 6.3% Asian, 0.7% Pacific Islander, 10.5% some other race, and 4.2% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino people of any race were 24.3% of the population.[49] Non-Hispanic Whites were 62.5% of the population in 2010,[49] down from 88.5% in 1980.[50]

At the 2010 census, there were 90,924 households, of which 29.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 38.4% were headed by married couples living together, 11.8% had a female householder with no husband present, and 43.8% were non-families. 32.1% of all households were made up of individuals, and 9.7% were someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.43, and the average family size was 3.10.[49]

In the city, the 2010 population was spread out, with 22.8% under the age of 18, 12.5% from 18 to 24, 28.2% from 25 to 44, 24.9% from 45 to 64, and 11.7% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 34.6 years. For every 100 females, there were 103.4 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 102.7 males.[49]

In 2011 the city's estimated median household income was $44,846, and the median family income was $53,896. Males had a median income of $42,120 versus $31,362 for females. The city's per capita income was $25,041. About 9.6% of families and 14.4% of the population were below the poverty line, including 15.1% of those under age 18 and 12.8% of those age 65 or over.[51][52] The population was 180,480 at the 2000 census; in 2010, its population had risen to 225,221, making it the third-largest city in the state after Las Vegas and Henderson, and the largest outside Clark County. Reno lies 26 miles (42 km) north of the Nevada state capital, Carson City, and 22 miles (35 km) northeast of Lake Tahoe in a shrub-steppe environment. Reno shares its eastern border with the city of Sparks and is the larger of the principal cities of the Reno–Sparks, Nevada Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA), a metropolitan area that covers Storey and Washoe counties.[53] The MSA had a combined population of 425,417 at the 2010 census.[54]

There is an Italian-American community in Reno.[55]

Economy

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2018) |

Until the 1960s, Reno was the gambling capital of the United States, but Las Vegas' rapid growth, American Airlines' 2000 buyout of Reno Air, and the growth of Native American gaming in California have reduced its gambling economy. Older casinos were torn down (Mapes Hotel, Fitzgerald's Nevada Club, Primadonna, Horseshoe Club, Harold's Club, Palace Club), or smaller casinos like the Comstock, Sundowner, Golden Phoenix, Kings Inn, Money Tree, Virginian, and Riverboat were either closed or were converted into residential units.

Because of its location, Reno has traditionally drawn the majority of its California tourists and gamblers from the San Francisco Bay Area and Sacramento while Las Vegas has historically served more tourists from Southern California and the Phoenix area.

Several local large hotel casinos have shown significant growth and have moved gaming further away from the downtown core. These larger hotel casinos are the Atlantis, the Peppermill and the Grand Sierra Resort. The Peppermill was chosen as the most outstanding Reno gaming/hotel property by Casino Player and Nevada magazines. In 2005, the Peppermill Reno began a $300 million Tuscan-themed expansion.

Reno holds several events throughout the year to draw tourists to the area. They include Hot August Nights[56] (a classic car convention), Street Vibrations (a motorcycle fan gathering and rally), The Great Reno Balloon Race, a Cinco de Mayo celebration, bowling tournaments (held in the National Bowling Stadium), and the Reno Air Races.

Several large commercial developments were constructed during the mid-2000s boom, such as The Summit in 2007 and Legends at Sparks Marina in 2008.

Reno is the location of the corporate headquarters for several companies, including Braeburn Capital, Hamilton, Server Technology, EE Technologies, Caesars Entertainment, and Port of Subs. Companies based in the Reno metropolitan area include Sierra Nevada Corporation and U.S. Ordnance. International Game Technology, Bally Technologies and GameTech have a development and manufacturing presence.

Since the turn of the 21st century, greater Reno saw an influx of technology companies entering the area, following major initiatives and investments by investors from Seattle & the Bay Area. The first one in 1999 was Amazon.com in Fernley. After the Great Recession, the state placed an increased focus on economic development. Thousands of new jobs were created.[57][58][59][60][61]

The Tesla Gigafactory at the Tahoe Reno Industrial Center is one of the largest buildings in the country, purportedly covering 5.8 million square feet.[62][58][59][60][61] Although it was originally Tesla's largest factory, it's since been superseded by Gigafactory Texas, which has 10 million square feet.[63] It employs roughly 11,000 people, making Tesla larger than any employer in the city of Reno, though the Industrial Center is located just outside of the city.[64] In 2023 Tesla announced a $3.6 billion expansion[65] of the facility that would incorporate an additional four million square feet, including an all-new plant for Semis and a much larger one for battery development. The new facilities are expected to add up to 3,000 new Tesla employees to the region upon completion.[66]

The arrival of several data centers at the Tahoe Reno Industrial Center is further diversifying a region that was best known for distribution and logistics outside gaming and tourism. Switch's new SUPERNAP campus at the Tahoe Reno Industrial Center is shaping up to be the largest data center in the world once completed. Apple is expanding its data center at the adjacent Reno Technology Park and recently built a warehouse on land in downtown Reno.

The greater Reno area also hosts distribution facilities for Amazon, Walmart, PetSmart and Zulily.[67]

Top employers

editAccording to Reno's 2023 Fiscal Year Annual Comprehensive Financial Report,[68] the top employers in the city are:

| # | Employer | Average

Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Washoe County School District | 7,500 |

| 2 | Renown Regional Medical Center | 7,500 |

| 3 | Washoe County | 3,000 |

| 4 | Peppermill Reno | 3,000 |

| 5 | Nugget Casino Resort | 3,000 |

| 6 | Harrah's Reno Casino | 3,000 |

| 7 | Grand Sierra Resort | 3,000 |

| 8 | Saint Mary's Regional Medical Center | 3,000 |

| 9 | Eldorado Resort Casino | 3,000 |

| 10 | Silver Legacy Resort Casino | 3,000 |

Healthcare

editReno has several healthcare facilities. Many are affiliated with the University of Nevada Reno School of Medicine.

- Northern Nevada Medical Center

- Northern Nevada Sierra Medical Center

- Renown Regional Medical Center

- Saint Mary's Regional Medical Center

- University of Nevada Reno School of Medicine

- Veteran's Administration Sierra Nevada Healthcare System Reno, Nevada

Arts and culture

editReno has several museums. The Nevada Museum of Art is the only American Alliance of Museums (AAM) accredited art museum in Nevada.[69] The National Automobile Museum contains 200 cars that were from the collection of William F. Harrah, including Elvis Presley's 1973 Cadillac Eldorado.[70]

Reno also hosts a number of music venues, such as the Pioneer Center for the Performing Arts, the Reno Philharmonic Orchestra, and the Reno Pops Orchestra. The Reno Youth Symphony Orchestra (YSO), affiliated with the Reno Philharmonic, gives talented youth the opportunity to play advanced music and perform nationwide.[71] In 2016 they had the honor of performing at Carnegie Hall. A.V.A. Ballet Theatre is the resident ballet company of the Pioneer Center for the Performing Arts. All of their classical performances are with the Reno Philharmonic Orchestra.

Every July, Reno celebrates Artown, a visual and performing arts festival that lasts the entire month of July throughout the city. Along with performances, Artown partners with other institutions throughout the Reno Tahoe area to hold workshops, camps, and classes for all ages. All events are free of charge or low cost.[72]

Reno has a public library, a branch of the Washoe County Library System. The Downtown branch of the Washoe County Library was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2013.[73]

Sports

editReno is home to the Reno Aces, the minor league baseball Triple-A affiliate of the Arizona Diamondbacks, playing in Greater Nevada Field, a downtown ballpark opened in 2009. Reno has hosted multiple professional baseball teams in the past, most under the Reno Silver Sox name. The Reno Astros, a former professional, unaffiliated baseball team, played at Moana Stadium until 2009.

In basketball, the Reno Bighorns of the NBA G League played at the Reno Events Center from 2008 to 2018.[74] They were primarily an affiliate of the Sacramento Kings throughout its existence. The Sacramento Kings bought the team in 2016 and moved the franchise to become the Stockton Kings in 2018.

Reno is host to both amateur and professional combat sporting events such as mixed martial arts and boxing. The "Fight of the Century" between Jack Johnson and James J. Jeffries was held in Reno in 1910.[75] Boxer Ray Mancini fought four of his last five fights in Reno against Bobby Chacon, Livingstone Bramble, Héctor Camacho and Greg Haugen.[76]

Reno expected to be the future home of an ECHL ice hockey team, named the Reno Raiders, but construction on a suitable arena never began. The franchise was dormant since 1998, when it was named the Reno Rage, and earlier the Reno Renegades, and played in the now-defunct West Coast Hockey League (WCHL). In 2016, Reno was removed from the ECHL's Future Markets page.

The Reno–Tahoe Open is northern Nevada's only PGA Tour event, held at Montrêux Golf & Country Club in Reno. As part of the FedEx Cup, the tournament follows 132 PGA Tour professionals competing for a share of the event's $3 million purse. The Reno-Tahoe Open Foundation has donated more than $1.8 million to local charities.

Reno has a college sports scene, with the Nevada Wolf Pack appearing in football bowl games and an Associated Press and Coaches Poll Top Ten ranking in basketball in 2018.

In 2004, the city completed a $1.5 million whitewater park on the Truckee River in downtown Reno which hosts whitewater events throughout the year. The course runs Class 2 and 3 rapids with year-round public access. The 1,400-foot (430 m) north channel features more aggressive rapids, drop pools and "holes" for rodeo kayak-type maneuvers. The milder 1,200 ft (370 m) south channel is set up as a kayak slalom course and a beginner area.

Reno is home to two roller derby teams, the Battle Born Derby Demons and the Reno Roller Girls.[77] The Battle Born Derby Demons compete on flat tracks locally and nationally. They are the only derby team locally to compete in a national Derby league.

Reno is the home of the National Bowling Stadium, which hosts the United States Bowling Congress (USBC) Open Championships every three years.

List of teams

editMinor professional teams

edit| Team | Sport | League | Venue (capacity) | Established | Titles |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reno Aces | Baseball | MiLB (AAA-PCL) | Greater Nevada Field (9,013) | 2009 | 2 |

| Nevada Storm | Women's football | WFA | Damonte Ranch High School (N/A) Fernley High School (N/A) Galena High School (N/A) |

2008 | 2 |

Amateur teams

edit| Team | Sport | League | Venue (capacity) | Established | Titles |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reno Ice Raiders | Ice hockey | MWHL | Reno Ice | 2015 | 0 |

| Nevada Coyotes FC | Soccer | UPSL | Rio Vista Sports Complex (N/A) | 2016 | 0 |

College teams

edit| School | Team | League | Division | Primary conference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| University of Nevada, Reno (UNR) | Nevada Wolf Pack | NCAA | NCAA Division I | Mountain West |

| Western Nevada College (WNC) | WNC Wildcats | NJCAA | NJCAA Division I | Scenic West |

Parks and recreation

editReno is home to a variety of recreation activities including both seasonal and year-round. In the summer, Reno locals can be found near three major bodies of water: Lake Tahoe, the Truckee River, and Pyramid Lake. The Truckee River originates at Lake Tahoe and flows west to east through the center of downtown Reno before terminating at Pyramid Lake to the north. The river is a major part of Artown, held in the summer at Wingfield Park. Washoe Lake is a popular kite and windsurfing location because of its high wind speeds during the summer.

Skiing and snowboarding are among the most popular winter sports and draw many tourists. There are 18 ski resorts[78] (8 major resorts) as close as 11 miles (18 km) and as far as 98 miles (158 km) from the Reno–Tahoe International Airport, including Northstar California, Sierra-at-Tahoe, Alpine Meadows, Palisades Tahoe, Sugar Bowl, Diamond Peak, Heavenly Mountain, and Mount Rose. Other popular Reno winter activities include snowshoeing, ice skating, and snowmobiling. There are many bike paths to ride in the summer time. Lake Tahoe hosts international bike competitions each summer.

Air races

editThe Reno Air Races, also known as the National Championship Air Races, are held each September at the Reno Stead Airport. 2023 will mark the final year for the races in Reno after 60 years, as a result of the Reno Tahoe Airport Authority decision to sundown the event, citing growth around the airport amongst other nonspecific concerns not stated from the RTAA[79][80][81]

Government

editReno has a democratic municipal government. The city council is the core of the government, with seven members. Five of these council people represent districts of Reno, and are vetted in the primary by the citizens of each district. In general, the top two vote earners in each ward make the ballot for the citywide election. The other two council members are the at-large member, who represents the entire city, and the mayor, who is elected by the people of the city. The council has several duties, including setting priorities for the city, promoting communication with the public, planning development, and redevelopment.

There is an elected city attorney who is responsible for civil and criminal cases. The City Attorney represents the city government in court, and prosecutes misdemeanors.

The city's charter calls for a council-manager form of government, meaning the council appoints only two positions, the city manager, who implements and enforces the policies and programs the council approves, and the city clerk. The city manager is in charge of the budget and workforce for all city programs. The city clerk, who records the proceedings of the council, makes appointments for the council, and makes sure efficient copying and printing services are available.

In 2010, there was a ballot question asking whether the Reno city government and the Washoe County government should explore the idea of becoming one combined governmental body.[82] Fifty-four percent of voters approved of the ballot measure to make an inquiry into consolidating the governments.[83]

Fire department

editThe city of Reno is protected by the Reno Fire Department (RFD) manning 14 fire stations.[84][85]

The Reno Fire Department (RFD) provides all-risk emergency service to the City of Reno residents. All-risk emergency service is the national model of municipal fire departments, providing the services needed in the most efficient way possible.[86]

The department provides paramedic-level service to the citizens and visitors of Reno. This is the highest level of emergency medical care available in the field.

In addition to responding to fires, whether they occur in structures, vegetation/brush or vehicles, the fire department also provides rescue capabilities for almost any type of emergency situation.

This includes quick and efficient emergency medical care for the citizens; a hazardous materials team capable of identifying unknown materials and controlling a release disaster; and preparedness and management of large-scale incidents.

Maintaining this level of service requires nearly constant training of personnel. This training maintains both the skills needed to operate safely in emergency environments and the physical fitness necessary to reduce the likelihood and severity of injuries.

The minimum annual-training requirement to maintain firefighting and medical skills is 240 hours per year. Special teams and company-level drills add significantly to that number of hours.[87]

Education

editUniversities and colleges

edit- The University of Nevada, Reno is the oldest university in Nevada and Nevada System of Higher Education. In 1886, the state university, previously only a college preparatory school, moved from Elko in remote northeastern Nevada to north of downtown Reno, where it became a full-fledged state college.[88] The university grew slowly over the decades, but it now has an enrollment of 21,353,[89] with most students from within Nevada. Its specialties include mining engineering, agriculture, journalism, business, and one of only two Basque Studies programs in the nation. It houses the National Judicial College. The university was named one of the top 200 colleges in the nation in the most recent U.S. News & World Report National Universities category index.[90]

- Truckee Meadows Community College (TMCC) is a regionally accredited, two-year institution which is part of the Nevada System of Higher Education. The college has approximately 13,000 students attending classes at a primary campus and four satellite centers. It offers a wide range of academic and university transfer programs, occupational training, career enhancement workshops, and other classes. TMCC offers associate of arts, associate of science, associate of applied science or associate of general studies degrees, one-year certificates, or certificates of completion in more than 50 career fields, including architecture, auto/diesel mechanics, criminal justice, dental hygiene, graphic design, musical theatre, nursing, and welding.

- The Nevada School of Law at Old College in Reno was the first law school established in the state of Nevada. Its doors were open from 1981 to 1988.

Public schools

editPublic education is provided by the Washoe County School District.

- Reno has twelve public high schools: Damonte Ranch, Galena, Hug, North Valleys High School, McQueen, Academy of Arts, Careers, and Technology (AACT), Reno, Truckee Meadows Community College High School,[91] Innovations, Wooster and Debbie Smith Career and Technical Education Academy (Debbie Smith CTE, also under construction, taking the place of the old Hug Campus.)

- There are three public high schools in neighboring Sparks, attended by many students who live in Reno: Reed, Spanish Springs, and Sparks High School.

- Reno-Sparks has 15 middle schools: Billinghurst, Clayton, Cold Springs, Depoali, Dilworth, Herz, Mendive, O'Brien, Pine, Shaw, Sky Ranch, Sparks, Swope, Traner, and Vaughn.

- Reno-Sparks has 65 elementary schools: Allen, Anderson, Beasley, Jesse Beck, Bennett, Booth, Brown, Cannan, Caughlin Ranch, Corbett, Desert Heights, Diedrichsen, Dodson, Donner Springs, Double Diamond, Drake, Duncan, Katherine Dunn, Elmcrest, Gomes, Grace Warner, Greenbrae, Hidden Valley, Huffaker, Hunsberger, Hunter Lake, Jesse Beck, John C Bohach, Johnson, Juniper, Lemmon Valley, Elizabeth Lenz, Lincoln Park, Echo Loder, Mathews, Maxwell, Melton, Mitchell, Moss, Mount Rose, Natchez, Palmer, Peavine, Picollo Special Education School, Pleasant Valley, Risley, Roy Gomm, Sepulveda, Sierra Vista, Silver Lake, Alice Smith, Kate Smith, Smithridge, Spanish Springs, Stead, Sun Valley, Taylor, Towles, Van Gorder, Verdi [pronounced VUR-die], Veterans Memorial, Warner, Westergard, Whitehead, and Sarah Winnemucca. (some schools included on this list are in Sparks)

Public charter schools

editReno has many charter schools, which include Academy for Career Education, serving grades 10–12, opened 2002;[92] Alpine Academy Charter High School, serving grades 9–12, opened 2009;[93] Bailey Charter Elementary School, serving grades K-6, opened 2001;[94] Coral Academy of Science, serving grades K-12;[95] Davidson Academy, serving grades 6–12, opened 2006;[96] Doral Academy of Northern Nevada, serving grades K-8; High Desert Montessori School, serving grades PreK-7, opened 2002; I Can Do Anything Charter School, serving grades 9–12, opened 2000; Mariposa Language and Learning Academy, serving grades K-5; Mater Academy of Northern Nevada, serving grades K-8; Pinecrest Academy of Northern Nevada, serving grades K-8; Rainshadow Community Charter High School, serving grades 9–12, opened 2003;[97] Sierra Nevada Academy Charter School, serving grades PreK-8, opened 1999; and TEAM A (Together Everyone Achieves More Academy), serving grades 9–12, opened 2004.[98]

Private schools

editReno has a few private elementary schools such as Legacy Christian School, Excel Christian School, St. Nicholas Orthodox Academy,[99] Lamplight Christian School,[100] and Nevada Sage Waldorf School[101] as well as private high schools, the largest of which are Bishop Manogue High School[102] and Sage Ridge School.[103]

Transportation

editRoads

editReno was historically served by the Victory Highway and a branch of the Lincoln Highway. After the formation of the U.S. Numbered Highways system, U.S. Route 40 was routed along 4th Street through downtown Reno, before being replaced by Interstate 80. The primary north–south highway through Reno is U.S. Route 395/Interstate 580.

Bus

editThe Regional Transportation Commission of Washoe County (RTC) has a bus system that provides intracity buses, intercity buses to Carson City, and an on-demand shuttle service for disabled persons.[104] The system has its main terminal on 4th Street in downtown Reno and secondary terminals in Sparks and at Meadowood Mall in south Reno.

Numerous shuttle and excursion services are offered connecting the Reno–Tahoe International Airport to various destinations:

- North Lake Tahoe Express provides connecting shuttle service to North Lake Tahoe Resorts

- South Tahoe Airporter provides connecting shuttle service to South Lake Tahoe resorts.

- Eastern Sierra Transit Authority provides shuttles to destinations south along the US-395 corridor in California, such as Mammoth Mountain and Lancaster

- Modoc Sage Stage provides shuttles to Alturas and Susanville, California, along the northern US-395 corridor.

- Salt Lake Express provides service to Las Vegas mainly along the southern US-95 corridor.

Greyhound stops at a downtown terminal. Megabus stopped at the Silver Legacy Reno, but has since discontinued service to Reno.[105]

Rail

editReno was historically a stopover along the First transcontinental railroad; the modern Overland Route continues to run through Reno. Reno was additionally the southern terminus of the Nevada–California–Oregon Railway (NCO) and the northern terminus of the Virginia and Truckee Railroad. Using the NCO depot and right of way, the Western Pacific Railroad also provided rail service to Reno. In the early 20th century, Reno also had a modest streetcar system. Downtown Reno has two historic train depots, the inactive Nevada-California-Oregon Railroad Depot and the active Amtrak depot at Reno station, originally built by the Southern Pacific Railroad.[106]

Amtrak provides daily passenger service to Reno via the California Zephyr at Reno station and via multiple Amtrak Thruway buses that connect to trains departing from Sacramento.

Air

editThe city is served by Reno–Tahoe International Airport, with general aviation traffic handled by Reno Stead Airport. Reno–Tahoe International Airport is the second busiest commercial airport in the state of Nevada after Harry Reid International Airport in Las Vegas. Reno was the hub and headquarters of the defunct airline Reno Air.

Utilities

editThe Truckee Meadows Water Authority provides potable water for the city. The Truckee River is the primary water source. It supplies Reno with 80 million U.S. gallons (300 Ml) of water a day during the summer, and 40 million U.S. gallons (150 Ml) of water per day in the winter. The two water treatment plants are Chalk Bluff and Glendale. The Chalk Bluff plant's main intakes are west of Reno and south of Verdi, with the water flowing through a series of flumes and ditches to the plant. Alternative intakes are below the plant along the banks of the Truckee River itself. The Glendale plant is alongside the river, and is fed by a rock and concrete rubble diversion dam a short distance upstream.[107]

Sewage treatment for most of the Truckee Meadows region takes place at the Truckee Meadows Water Reclamation Facility at the eastern edge of the valley. Treated effluent returns to the Truckee River by way of Steamboat Creek.[108] In the 1990s, this capacity was increased from 20 to 30 million U.S. gallons (70 to 110 million liters) per day. While treated, the effluent contains suspended solids, nitrogen, and phosphorus, aggravating water-quality concerns of the river and its receiving waters of Pyramid Lake. Local agencies working with the Environmental Protection Agency have developed several watershed management strategies to accommodate this expanded discharge. To accomplish this successful outcome, the DSSAM Model was developed and calibrated for the Truckee River to analyze the most cost-effective available management strategy set.[109] The resulting management strategies included measures such as land use controls in the Lake Tahoe basin, urban runoff controls in Reno and Sparks, and best management practices for wastewater discharge.[citation needed] Golf courses in Reno have been using treated effluent water rather than treated water from one of Reno's water plants.[citation needed]

NV Energy, formerly Sierra Pacific, provides electric power and natural gas. Power comes from multiple sources, including Tracy-Clark Station to the east, and the Steamboat Springs binary cycle power plants at the southern end of town.[110]

Notable people

editIn popular culture

editMovies filmed in Reno include:

- The Cooler[111]

- Magnolia[112]

- Hard Eight[113]

- Charley Varrick[114]

- Into the Wild

- Desert Hearts[115]

- The Wizard[116]

- Jinxed![15]

- The Misfits[15]

- Kingpin[117]

- ...All the Marbles[118]

- Pink Cadillac[15]

- Diamonds[119]

- Sister Act[120]

- Father's Day[121]

- Waking Up in Reno[122]

- Austin Powers in Goldmember[123]

- Jane Austen's Mafia![citation needed]

- 40 Pounds of Trouble[citation needed]

- California Split[124]

- Up Close & Personal[125]

- The Pledge[126]

- Kill Me Again[125]

- The Last Don[127]

- Ocean's Eleven[21]

- Andy Hardy's Blonde Trouble[128]

- Blind Fury[129]

- Melvin and Howard[citation needed]

- Mr. Belvedere Goes to College[130]

- Scarecrow[131]

- Wild Is the Wind[citation needed]

- Born to Kill[132]

- The Muppets[133]

- Promised Land[citation needed]

- The Motel Life[citation needed]

- 5 Against the House[citation needed]

Reno is featured in the post-apocalyptic roleplaying game Fallout 2, as New Reno.[134] It is also mentioned in the Johnny Cash song Folsom Prison Blues. The final two episodes of Knuckles had additional filming take place in Reno, as the episodes featured the city prominently.[135]

Twin towns – sister cities

editReno's sister cities are:[136]

- San Sebastián, Spain

- Taichung, Taiwan

- Udon Thani, Thailand

- Wirral, England, United Kingdom

- Nalchik, Russian Federation

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Mean maxima and minima (i.e., the highest and lowest temperature readings during an entire month or year) calculated based on data at said location from 1991 to 2020.

- ^ Official records for Reno kept January 1893 to 10 November 1905 at "Reno", 11 November 1905 to February 1937 at Reno Weather Bureau Office (CRB), and at Reno–Tahoe International Airport since March 1937. For more information, see Threadex

- ^ Mean maxima and minima (i.e., the highest and lowest temperature readings during an entire month or year) calculated based on data at said location from 1991 to 2020.

References

edit- ^ "ArcGIS REST Services Directory". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 19, 2022.

- ^ a b U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Reno, Nevada

- ^ a b c "Census - Geography Profile: Reno city, Nevada". Retrieved April 21, 2022.

- ^ "City of Reno: Home". Reno.gov. Archived from the original on May 11, 2012. Retrieved January 16, 2013.

- ^ "QuickFacts – Reno city, Nevada". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 1, 2019.

- ^ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2017 -United States – Metropolitan Statistical Area; and for Puerto Rico – 2017 Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved September 11, 2018.

- ^ Brauman, Sharon K. (October 6, 2004). "North Fork petroglyphs". ucnrs.org. Archived from the original on July 24, 2008. Retrieved August 15, 2008.

- ^ Haddad, Evan (January 11, 2023). "Midtown, Reno: A business graveyard or the boomtown of Washoe County?". Ventura County Star. Retrieved January 13, 2023.

- ^ Guy Louis Rocha, "Reno's First Robber Baron," Nevada Magazine 40,2 (March–April 1980), p. 28.

- ^ "History of Reno". City of Reno. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved July 13, 2014.

- ^ "NEVADA HISTORICAL SOCIETY QUARTERLY" (PDF). epubs.nsla.nv.gov. Retrieved September 11, 2023.

- ^ Cegavske, Barbara .K. (2016). Political History of Nevada. Nevada.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "Visit Reno, Nevada!". www.iise.org. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- ^ John_O'Neill_100001295309124 (January 9, 2008). "ReviewJournal.com – News – Gold hits record high". Lvrj.com.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Land, Barbara; Myrick Land (1995). A short history of Reno. Reno, Nevada: University of Nevada Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-87417-262-1.

- ^ a b c Brean, Henry (September 18, 2017). "The rise and fall of Reno's quickie divorce industry". Reno Gazette-Journal. Las Vegas Review-Journal. Retrieved March 8, 2020.

- ^ "Ad for R. Herz & Bro. Jewelers". Reno Divorce History. Retrieved September 1, 2021.

- ^ Harmon, Mella. "El Cortez Hotel". Reno Historical. Retrieved September 1, 2021.

- ^ Wernick, Robert (June 1996). "Where You Went if You Really Had to Get Unhitched". Retrieved March 15, 2024.

- ^ "Famous people divorced in Reno". Reno Divorce History. 2014. Retrieved March 15, 2024.

- ^ a b c Barber, Alicia (2008). Reno's big gamble: image and reputation in the biggest little city. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-1594-0.

- ^ Barber, Alicia. "Tour | Historic Gambling Clubs and Casinos". Reno Historical. Retrieved July 4, 2024.

- ^ Moe, Al W. The Roots of Reno, [1], 2008, p.153

- ^ Moe, Al W. Nevada's Golden Age of Gambling, Puget Sound Books, 2002, p.68

- ^ Fenwick, Jerry (January 1, 2015). "Disaster on Sierra Street" (PDF). Historic Reno Preservation Society. Retrieved July 3, 2024.

- ^ "Town Building (1868-1912) | 4th Street Prater Way History Project". 4thprater.onlinenevada.org. Retrieved July 4, 2024.

- ^ Onishi, Norimitsu (July 14, 2012). "With Gambling in Decline, Reno Struggles to Reinvent Itself". The New York Times.

- ^ "Tahoe Skiing and Snowboard". Visit Reno Tahoe. 2019. Retrieved August 30, 2019.

- ^ "PHOTOS: Reno's New Flag Flying High". This Is Reno. May 28, 2018.

- ^ Weise, Karen (June 22, 2017). "Reno is Starting to Look More Like Silicon Valley". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on December 21, 2019. Retrieved March 30, 2022.

- ^ Ashley Powers; Thomas H. Maugh II (April 30, 2008). "Swarm of earthquakes shakes Reno area". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 27, 2008.

- ^ Kappele, William (2019). "Introduction". Rockhounding Nevada: A Guide to the State's Best Rockhounding Sites (3rd ed.). Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-4930-3402-4.

- ^ Weather and Climate of the Reno-Carson City-Lake Tahoe Region: Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology Special Publication 34. NV Bureau of Mines & Geology. 2007. p. 53. ISBN 978-1-888035-11-7. Retrieved January 16, 2013.

- ^ Magerum, Liz (January 20, 2012). "'Remorseful' man admits he caused Reno blaze". USA Today. Associated Press. Retrieved February 2, 2012.

- ^ O'Hara, B. F. (2006). Climate of Reno, Nevada. p. 1

- ^ a b O'Hara, B. F. (2006). Climate of Reno, Nevada. p. 4

- ^ Loría-Salazar, S. Marcela; Arnott, W. Patrick; Moosmüller, Hans (2014). "Accuracy of near-surface aerosol extinction determined from columnar aerosol optical depth measurements in Reno, NV, USA". Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres. 119 (19). Bibcode:2014JGRD..11911355L. doi:10.1002/2014JD022138.

- ^ a b c d "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved October 13, 2021.

- ^ "Reno, NV". Reno Tahoe Visitors website. Archived from the original on January 6, 2009. Retrieved June 1, 2010.

- ^ Brian O'Hara; Gary Barbato; John James; Heather Angeloff; Tom Cylke (2007). Weather and Climate of the Reno-Carson City-Lake Tahoe Region. NV Bureau of Mines & Geology. p. 71. ISBN 978-1-888035-11-7.

- ^ "National Weather Service Climate". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved October 13, 2021.

- ^ "Summary of Monthly Normals 1991–2020". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on June 30, 2023. Retrieved October 13, 2021.

- ^ "WMO Climate Normals for NV Reno Tahoe INTL AP 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on June 30, 2023. Retrieved February 12, 2017.

- ^ US Department of Commerce, NOAA. "Climate". www.weather.gov. Retrieved June 13, 2024.

- ^ Moffatt, Riley (1996). Population History of Western U.S. Cities & Towns, 1850–1990. Lanham: Scarecrow. p. 158. ISBN 9780810830332.

- ^ "P004: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2000: DEC Summary File 1 – Reno city, Nevada". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P2: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Reno city, Nevada". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P2: Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Reno city, Nevada". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ a b c d "Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (DP-1): Reno city, Nevada". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 15, 2013.

- ^ "Nevada – Race and Hispanic Origin for Selected Cities and Other Places: Earliest Census to 1990". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on August 12, 2012. Retrieved April 21, 2012.

- ^ "Selected Economic Characteristics: 2011 American Community Survey 1-Year Estimates (DP03): Reno city, Nevada". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 15, 2013.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ Metropolitan statistical areas and components Archived May 26, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, Office of Management and Budget, May 11, 2007. Retrieved July 30, 2008.

- ^ "Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (DP-1): Reno-Sparks, NV Metro Area". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 15, 2013.

- ^ "Explore Reno's Little Italy – did you know we had one?".

- ^ "Hot August Nights". Hot August Nights. Retrieved August 12, 2010.

- ^ Valley, Jackie (August 16, 2017). "Manufacturing jobs in Nevada see double-digit wage growth since recession". The Nevada Independent. Retrieved September 9, 2017.

- ^ a b "From Northern Nevada". Devine Intermodal. January 9, 2017. Retrieved September 9, 2017.

- ^ a b McGinness, Brett. "Would Amazon consider Reno-Sparks for its new headquarters?". Reno Gazette Journal.

- ^ a b Hidalgo, Jason. "Here's how Reno attracted the likes of Amazon, and created a distribution and shipping mecca". Reno Gazette Journal.

- ^ a b "Reno attains higher ratings with economic boost from tech companies". March 22, 2018.

- ^ Valley, Jackie (August 16, 2017). "Manufacturing jobs in Nevada see double-digit wage growth since recession". The Nevada Independent. Retrieved September 9, 2017.

- ^ Weatherbed, Jess (January 11, 2023). "Tesla is planning a $770 million expansion of its Texas Gigafactory". The Verge. Retrieved January 12, 2024.

- ^ Murphy, Mike (January 2023). "Tesla's $3.6 Billion Expansion Plans At Giga Nevada". CleanTechnica. Retrieved January 12, 2024.

- ^ Margiott, Ben (January 24, 2023). "Tesla announces new $3.5B facility east of Sparks to build all-electric semi trucks". KRNV. Retrieved July 4, 2024.

- ^ Murphy, Mike (January 25, 2023). "Tesla says it plans $3.6 billion expansion of Nevada gigafactory". MarketWatch. Retrieved January 12, 2024.

- ^ Damon, Anjeanette (October 29, 2019). "High heels, high tech, high stakes: What happened when Reno tried to kick out its strip clubs". USS Today. Retrieved October 29, 2019.

- ^ "City of Reno CAFR". City of Reno. 2023. p. 158. Retrieved August 20, 2024.

- ^ "About the Museum". Nevada Museum of Art. Retrieved September 22, 2017.

- ^ Taylor, Michael (February 25, 2007). "The Last Of Harrah / Enough of Reno tycoon's car collection is left to fill a museum".

- ^ "Youth Symphony Orchestra". Reno Phil. Retrieved November 24, 2017.

- ^ Kane, Jenny. "Artown 2021 festival: What you should know, what you don't want to miss". Reno Gazette Journal. Retrieved December 10, 2021.

- ^ Trexler, Susie; Fogelquist, Sara (August 12, 2012). "National Register of Historic Places Registration: Washoe County Library / Downtown Library or Downtown Reno Library" (PDF). National Park Service.

- ^ "NBA Development League: The D-League Expands to Reno". Nbareno.com. Retrieved January 16, 2013.

- ^ Borrowman, Shane (May–June 2010). "Celebrating Jack Johnson". Nevada Magazine. Archived from the original on March 18, 2012. Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- ^ "Ray Mancini-Boxer". Retrieved April 11, 2011.

- ^ Daniel Riggs (2008). "There are two roller derby organizations in Reno—and don't ever make the mistake of confusing one for the other". newsreview.com. Retrieved August 14, 2010.

- ^ "About Reno-Sparks". Reno Sparks Chamber of Commerce. Archived from the original on July 27, 2011. Retrieved September 3, 2011.

- ^ "Celebrating 50 years of the Reno Air Races". Reno Gazette-Journal. September 16, 2013. Retrieved October 18, 2014.

- ^ "FAQs". The Reno Air Racing Association. Retrieved October 18, 2014.

- ^ "National Championship Air Races Reno Air Races". Retrieved May 7, 2023.

- ^ Voyles, Susan (October 24, 2010). "Combining local governments is questioned on ballot issue". Reno Gazette-Journal. p. 10A.

- ^ "Election Results: Nevada". The New York Times. Retrieved November 3, 2010.

- ^ "City of Reno: Fire Department". Reno.gov. March 20, 2013. Archived from the original on January 18, 2013. Retrieved May 4, 2013.

- ^ "City of Reno: Administration". Reno.gov. March 20, 2013. Archived from the original on January 19, 2013. Retrieved May 4, 2013.

- ^ "Reno Fire Department – City of Reno". www.reno.gov.

- ^ "2017 Reno Fire Department: Annual Report by City of Reno - Issuu". issuu.com. April 3, 2017.

- ^ A History of the University of Nevada, Reno. University of Nevada, Reno. Retrieved 2020-06-22

- ^ "Slower enrollment growth strategy still sets record of 21,353 students". University of Nevada, Reno. Retrieved April 6, 2017.

- ^ "Best Colleges | Search". US News. Archived from the original on January 16, 2013. Retrieved January 16, 2013.

- ^ "TMCC High School". Tmcc.edu. Archived from the original on May 18, 2015.

- ^ "ACE High School". ACE High School. Retrieved January 16, 2013.

- ^ "Alpine Academy Charter High School – Sparks, Nevada". Alpineacademy.net. Retrieved January 16, 2013.

- ^ "School Brief". Baileycharter.org. Archived from the original on April 23, 2013. Retrieved January 16, 2013.

- ^ "Home page". Coral Academy of Science. March 10, 2012.

- ^ Sandra Chereb (August 4, 2009). "No genius left behind? Reno academy caters to smart students". USA Today. Associated Press. Retrieved November 15, 2011.

- ^ "Rainshadow Community Charter High School". Rainshadowcchs.org. Retrieved January 16, 2013.

- ^ "TEAM A Official site". Teammartialartsacademy. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved August 12, 2010.

- ^ "Private Christian School in Reno, Nevada – St. Nicholas Orthodox Academy". Retrieved January 2, 2019.

- ^ "Lamplight Christian School". Lcsreno.com. Retrieved January 16, 2013.

- ^ "Nevada sage waldorf school". nevadasagewaldorf.org. Retrieved September 24, 2014.

- ^ "Bishop Manogue Catholic High School – Home". Bishopmanogue.org. February 29, 2012.

- ^ "Sage Ridge School". Sageridge.org.

- ^ "RTC Washoe". RTC Washoe. Archived from the original on November 30, 2010. Retrieved August 12, 2010.

- ^ "Megabus ending Reno service on January 10". Reno-Gazette Journal. Retrieved March 19, 2018.

- ^ Albright, Willie (July 14, 2011). "We told you so". Reno News & Review. Retrieved July 23, 2017.

- ^ "Truckee Meadows Water Authority".

- ^ "Truckee Meadows Water Reclamation Facility". Archived from the original on February 7, 2016. Retrieved January 16, 2013.

- ^ C. Michael Hogan, Marc Papineau et al. 1987. Development of a dynamic water quality simulation model for the Truckee River, Earth Metrics Inc., Environmental Protection Agency Technology Series, Washington D.C.

- ^ "Steamboat Springs Geothermal Field | ONE". www.onlinenevada.org. Retrieved September 12, 2021.

- ^ Benson, Sara (2008). Lonely Planet Las Vegas City Guide. Lonely Planet. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-74104-677-9.

- ^ DuVal (2002), p. 117.

- ^ DuVal (2002), p. 79.

- ^ DuVal (2002), p. 38.

- ^ DuVal (2002), p. 51.

- ^ Catalano, Grace (1991). Fred Savage: Totally Awesome. Bantam Books. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-553-28858-2.

- ^ Didinger, Ray; Glen Macnow (2009). The Ultimate Book of Sports Movies: Featuring the 100 Greatest Sports Films of All Time. Running Press. p. 216. ISBN 978-0-7624-3548-7.

- ^ DuVal (2002), p. 11.

- ^ Maltin, Leonard (2008). Leonard Maltin's 2009 Movie Guide. Penguin. p. 351. ISBN 978-0-452-28978-9.

- ^ Turan, Kenneth (2006). Now in theaters everywhere: a celebration of a certain kind of blockbuster. PublicAffairs. p. 149. ISBN 978-1-58648-395-1.

- ^ DuVal (2002), p. 19.

- ^ Bleiler, David (2003). Tla Video & Dvd Guide 2004: The Discerning Film Lover's Guide. Macmillan. p. 655. ISBN 978-0-312-31686-0.

- ^ D'Arc, James V. (2010). When Hollywood Came to Town. Gibbs Smith. p. 302. ISBN 978-1-4236-0587-4.

- ^ DuVal (2002), p. 13.

- ^ a b DuVal (2002), p. 177.

- ^ McDougal, Dennis (2008). Five easy decades: how Jack Nicholson became the biggest movie star in modern times. John Wiley and Son. p. 371. ISBN 978-0-471-72246-5.

- ^ DuVal (2002), p. 107.

- ^ DuVal (2002), p. 5.

- ^ Emery, Robert J. (2003). The directors: take four. Allworth Communications, Inc. p. 73. ISBN 978-1-58115-279-1.

- ^ DuVal (2002), p. 125.

- ^ DuVal (2002), p. 220.

- ^ DuVal (2002), p. 25.

- ^ Curley, Rob (November 23, 2011). "Reaction in Reno to 'The Muppets' might not be all laughs". Las Vegas Sun. Retrieved June 3, 2024.

- ^ Norton, Matthew J. (1998). Fallout 2 Official Strategies & Secrets. Sybex. p. 156. ISBN 0782124151.

- ^ Hidalgo, Jason. "No, Reno is not 'Las Vegas for losers' says 'Knuckles' producer Toby Ascher". Reno Gazette Journal. Retrieved November 10, 2024.

- ^ "Sister Cities". reno.gov. City of Reno. Archived from the original on October 18, 2020. Retrieved October 23, 2020.

Bibliography

edit- Benson, Heather Lené. "In Place/Out of Place: Punjabi-Sikhs in Reno, Nevada" (PhD dissertation, University of Nevada, Reno, 2022) online.

- DuVal, Gary (2002). The Nevada filmography: nearly 600 works made in the state, 1897 through 2000. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-1271-6.

- Federal Writers' Project (1957), "Reno", Nevada: A Guide to the Silver State, American Guide Series, Portland, Or.: Binfords & Mort, hdl:2027/mdp.39015048749454 + Chronology

- Harpster, Jack. The Genesis of Reno: The History of the Riverside Hotel and the Virginia Street Bridge (University of Nevada Press, 2016).

- Moehring, Eugene P. Reno, Las Vegas, and the Strip: A Tale of Three Cities (University of Nevada Press, 2014).

- Moreno, Richard. A short history of Reno (University of Nevada Press, 2015).

- Price, John A. (1972). "Reno, Nevada: The City as a Unit of Study". Urban Anthropology. 1 (1): 014–028. JSTOR 40552854.

- Ringhoff, Mary, and Edward Stoner. The river and the railroad: An archaeological history of Reno (University of Nevada Press, 2011).

External links

edit- City of Reno official website Archived May 11, 2012, at the Wayback Machine