Hanukkah: Difference between revisions

BethNaught (talk | contribs) Reverted 1 edit by Jordandlee (talk): That spelling is acknowledged, but the article is called "Hanukkah" so we should use that. If you want to change that, file a move request. (TW) |

Jordandlee (talk | contribs) A menorah and Hanukia are two entirely different things (look it up before changing if you don't believe me). Also, 'sundown' is the proper term. Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

{{Infobox holiday |

{{Infobox holiday |

||

|image = Hanukia.jpg |

|image = Hanukia.jpg |

||

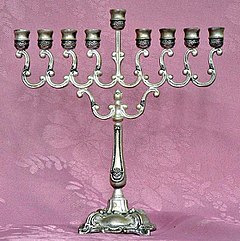

|caption = A |

|caption = A Hanukia |

||

|holiday_name = Hanukkah |

|holiday_name = Hanukkah |

||

|official_name = {{lang-he-n|חֲנֻכָּה}} or {{lang|he|חנוכה}}<br /> English translation: "Establishing" or "Dedication" (of the [[Temple in Jerusalem]]) |

|official_name = {{lang-he-n|חֲנֻכָּה}} or {{lang|he|חנוכה}}<br /> English translation: "Establishing" or "Dedication" (of the [[Temple in Jerusalem]]) |

||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

|significance = The [[Maccabees]] successfully rebelled against [[Antiochus IV Epiphanes]]. According to the [[Talmud]], a late text, the Temple was purified and the wicks of the menorah miraculously burned for eight days, even though there was only enough sacred oil for one day's lighting. |

|significance = The [[Maccabees]] successfully rebelled against [[Antiochus IV Epiphanes]]. According to the [[Talmud]], a late text, the Temple was purified and the wicks of the menorah miraculously burned for eight days, even though there was only enough sacred oil for one day's lighting. |

||

|relatedto = [[Purim]], as a [[rabbi]]nically decreed holiday. |

|relatedto = [[Purim]], as a [[rabbi]]nically decreed holiday. |

||

|date2014 = |

|date2014 = Sundown, 16 December to sundown, 24 December |

||

|date2015 = |

|date2015 = Sundown, 6 December to sundown, 14 December |

||

|date2016 = |

|date2016 = Sundown, 24 December to sundown, 1 January |

||

}} |

}} |

||

Revision as of 18:14, 29 November 2015

| Hanukkah | |

|---|---|

A Hanukia | |

| Official name | Template:Lang-he-n or חנוכה English translation: "Establishing" or "Dedication" (of the Temple in Jerusalem) |

| Observed by | Jews |

| Type | Jewish |

| Significance | The Maccabees successfully rebelled against Antiochus IV Epiphanes. According to the Talmud, a late text, the Temple was purified and the wicks of the menorah miraculously burned for eight days, even though there was only enough sacred oil for one day's lighting. |

| Celebrations | Lighting candles each night. Singing special songs, such as Ma'oz Tzur. Reciting Hallel prayer. Eating foods fried in oil, such as latkes and sufganiyot, and dairy foods. Playing the dreidel game, and giving Hanukkah gelt |

| Begins | 25 Kislev |

| Ends | 2 Tevet or 3 Tevet |

| Date | 25 Kislev, 26 Kislev, 27 Kislev, 28 Kislev, 29 Kislev, 30 Kislev, 1 Tevet, 2 Tevet, 3 Tevet |

| Related to | Purim, as a rabbinically decreed holiday. |

Hanukkah (/ˈhɑːnəkə/ HAH-nə-kə; Template:Lang-he-n khanuká, Tiberian: khanuká, usually spelled חנוכה, pronounced [χanuˈka] in Modern Hebrew, [ˈχanukə] or [ˈχanikə] in Yiddish; a transliteration also romanized as Chanukah or Ḥanukah), also known as the Festival of Lights and Feast of Dedication, is an eight-day Jewish holiday commemorating the rededication of the Holy Temple (the Second Temple) in Jerusalem at the time of the Maccabean Revolt against the Seleucid Empire of the 2nd century BC. Hanukkah is observed for eight nights and days, starting on the 25th day of Kislev according to the Hebrew calendar, which may occur at any time from late November to late December in the Gregorian calendar.

The festival is observed by the kindling of the lights of a unique candelabrum, the nine-branched menorah or hanukiah, one additional light on each night of the holiday, progressing to eight on the final night. The typical menorah consists of eight branches with an additional visually distinct branch. The extra light, with which the others are lit, is called a shamash (Template:Lang-he, "attendant")[1] and is given a distinct location, usually above or below the rest.

Other Hanukkah festivities include playing dreidel and eating oil based foods such as doughnuts and latkes.

Hanukkah became more widely celebrated beginning from the 1970s, when Rabbi Menachem M. Schneerson called for public awareness and observance of the festival and encouraged the lighting of public menorahs.[2][3][4][5] Diane Ashton attributed the popularization of Hanukkah by some of the American Jewish community as a way to adapt to American life, because they could celebrate Hannukkah which occurs at around the same time as Christmas.[6]

Etymology

The name "Hanukkah" derives from the Hebrew verb "חנך", meaning "to dedicate". On Hanukkah, the Maccabean Jews regained control of Jerusalem and rededicated the Temple.[7][8] Many homiletical explanations have been given for the name:[9]

- The name can be broken down into חנו כ"ה, "[they] rested [on the] twenty-fifth", referring to the fact that the Jews ceased fighting on the 25th day of Kislev, the day on which the holiday begins.[10]

- חנוכה (Hanukkah) is also the Hebrew acronym for ח נרות והלכה כבית הלל — "Eight candles, and the halakha is like the House of Hillel". This is a reference to the disagreement between two rabbinical schools of thought — the House of Hillel and the House of Shammai — on the proper order in which to light the Hanukkah flames. Shammai opined that eight candles should be lit on the first night, seven on the second night, and so on down to one on the last night (because the miracle was greatest on the first day). Hillel argued in favor of starting with one candle and lighting an additional one every night, up to eight on the eighth night (because the miracle grew in greatness each day). Jewish law adopted the position of Hillel.[11]

Historical sources

Maccabees, Mishna and Talmud

The story of Hanukkah is preserved in the books of the First and Second Maccabees, which describe in detail the re-dedication of the Temple in Jerusalem and the lighting of the menorah. These books are not part of the Tanakh (Hebrew Bible) which came from the Palestinian canon; however, they were part of the Alexandrian canon which is also called the Septuagint. Both books are included in the Old Testament used by the Catholic and Orthodox Churches,[12] since those churches consider the books deuterocanonical. They are not included in the Old Testament books in most Protestant Bibles, since most Protestants consider the books apocryphal. Multiple references to Hanukkah are also made in the Mishna (Bikkurim 1:6, Rosh HaShanah 1:3, Taanit 2:10, Megillah 3:4 and 3:6, Moed Katan 3:9, and Bava Kama 6:6), though specific laws are not described. The miracle of the one-day supply of oil miraculously lasting eight days is first described in the Talmud, committed to writing about 600 years after the events described in the books of Maccabees.[13]

Rav Nissim Gaon postulates in his Hakdamah Le'mafteach Hatalmud that information on the holiday was so commonplace that the Mishna felt no need to explain it. A modern-day scholar Reuvein Margolies[14] suggests that as the Mishnah was redacted after the Bar Kochba revolt, its editors were reluctant to include explicit discussion of a holiday celebrating another relatively recent revolt against a foreign ruler, for fear of antagonizing the Romans.

The Gemara (Talmud), in tractate Shabbat, page 21b, focuses on Shabbat candles and moves to Hanukkah candles and says that after the forces of Antiochus IV had been driven from the Temple, the Maccabees discovered that almost all of the ritual olive oil had been profaned. They found only a single container that was still sealed by the High Priest, with enough oil to keep the menorah in the Temple lit for a single day. They used this, yet it burned for eight days (the time it took to have new oil pressed and made ready).[15]

The Talmud presents three options:[16]

- The law requires only one light each night per household,

- A better practice is to light one light each night for each member of the household

- The most preferred practice is to vary the number of lights each night.

In Sephardic families, the head of the household lights the candles, while in Ashkenazic families, all family members light.[citation needed]

Except in times of danger, the lights were to be placed outside one's door, on the opposite side of the Mezuza, or in the window closest to the street. Rashi, in a note to Shabbat 21b, says their purpose is to publicize the miracle. The blessings for Hanukkah lights are discussed in tractate Succah, p. 46a.

Narrative of Josephus

The Jewish historian Titus Flavius Josephus narrates in his book, Jewish Antiquities XII, how the victorious Judas Maccabeus ordered lavish yearly eight-day festivities after rededicating the Temple in Jerusalem that had been profaned by Antiochus IV Epiphanes. Josephus does not say the festival was called Hanukkah but rather the "Festival of Lights":

- "Now Judas celebrated the festival of the restoration of the sacrifices of the temple for eight days, and omitted no sort of pleasures thereon; but he feasted them upon very rich and splendid sacrifices; and he honored God, and delighted them by hymns and psalms. Nay, they were so very glad at the revival of their customs, when, after a long time of intermission, they unexpectedly had regained the freedom of their worship, that they made it a law for their posterity, that they should keep a festival, on account of the restoration of their temple worship, for eight days. And from that time to this we celebrate this festival, and call it Lights. I suppose the reason was, because this liberty beyond our hopes appeared to us; and that thence was the name given to that festival. Judas also rebuilt the walls round about the city, and reared towers of great height against the incursions of enemies, and set guards therein. He also fortified the city Bethsura, that it might serve as a citadel against any distresses that might come from our enemies."[17]

Other ancient sources

The story of Hanukkah is alluded to in the book of 1 Maccabees and 2 Maccabees. The eight-day rededication of the temple is described in 1 Maccabees 4:36 et seq, though the name of the festival and the miracle of the lights do not appear here. A story similar in character, and obviously older in date, is the one alluded to in 2 Maccabees 1:18 et seq according to which the relighting of the altar fire by Nehemiah was due to a miracle which occurred on the 25th of Kislev, and which appears to be given as the reason for the selection of the same date for the rededication of the altar by Judah Maccabee.

Another source is the Megillat Antiochus. This work (also known as "Megillat Benei Ḥashmonai", "Megillat Hanukkah" or "Megillat Yevanit") is in both Aramaic and Hebrew; the Hebrew version is a literal translation from the Aramaic original. Recent scholarship dates it to somewhere between the 2nd and 5th Centuries, probably in the 2nd century,[18] with the Hebrew dating to the 7th century.[19] It was published for the first time in Mantua in 1557. Saadia Gaon, who translated it into Arabic in the 9th century, ascribed it to the elders of the School of Shammai and the School of Hillel.[20] The Hebrew text with an English translation can be found in the Siddur of Philip Birnbaum.

The Scroll of Antiochus concludes with the following words:

...After this, the sons of Israel went up to the Temple and rebuilt its gates and purified the Temple from the dead bodies and from the defilement. And they sought after pure olive oil to light the lamps therewith, but could not find any, except one bowl that was sealed with the signet ring of the High Priest from the days of Samuel the prophet and they knew that it was pure. There was in it [enough oil] to light [the lamps therewith] for one day, but the God of heaven whose name dwells there put therein his blessing and they were able to light from it eight days. Therefore, the sons of Ḥashmonai made this covenant and took upon themselves a solemn vow, they and the sons of Israel, all of them, to publish amongst the sons of Israel, [to the end] that they might observe these eight days of joy and honour, as the days of the feasts written in [the book of] the Law; [even] to light in them so as to make known to those who come after them that their God wrought for them salvation from heaven. In them, it is not permitted to mourn, neither to decree a fast [on those days], and anyone who has a vow to perform, let him perform it.

Original language (Aramaic):

בָּתַר דְּנָּא עָלוּ בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל לְבֵית מַקְדְּשָׁא וּבְנוֹ תַּרְעַיָּא וְדַכִּיאוּ בֵּית מַקְדְּשָׁא מִן קְטִילַיָּא וּמִן סְאוֹבֲתָא. וּבעוֹ מִשְׁחָא דְּזֵיתָא דָּכְיָא לְאַדְלָקָא בּוֹצִנַיָּא וְלָא אַשְׁכַּחוּ אֵלָא צְלוֹחִית חֲדָא דַּהֲוָת חֲתִימָא בְּעִזְקָת כָּהֲנָא רַבָּא מִיּוֹמֵי שְׁמוּאֵל נְבִיָּא וִיַדְעוּ דְּהִיא דָּכְיָא. בְּאַדְלָקוּת יוֹמָא חֲדָא הֲוָה בַּהּ וַאֲלָה שְׁמַיָּא דִּי שַׁכֵין שְׁמֵיהּ תַּמָּן יְהַב בַּהּ בִּרְכְּתָא וְאַדְלִיקוּ מִנַּהּ תְּמָנְיָא יוֹמִין. עַל כֵּן קַיִּימוּ בְּנֵי חַשְׁמוּנַּאי הָדֵין קְיָימָא וַאֲסַרוּ הָדֵין אֲסָּרָא אִנּוּן וּבְנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל כּוּלְּהוֹן. לְהוֹדָעָא לִבְנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל לְמֶעֲבַד הָדֵין תְּמָנְיָא יוֹמִין חַדְוָא וִיקָר כְּיּוֹמֵי מוֹעֲדַיָּא דִּכְתִיבִין בְּאוֹרָיְתָא לְאַדְלָקָא בְּהוֹן לְהוֹדָעָא לְמַן דְּיֵּיתֵי מִבַּתְרֵיהוֹן אֲרֵי עֲבַד לְהוֹן אֱלָהֲהוֹן פּוּרְקָנָא מִן שְׁמַיָּא. בְּהוֹן לָא לְמִסְפַּד וְלָא לְמִגְזַר צוֹמָא וְכָל דִּיהֵי עֲלוֹהִי נִדְרָא יְשַׁלְּמִנֵּיהּ[21]

In the Christian Greek Scriptures, it is stated that Jesus was at the Jerusalem Temple during "the Feast of Dedication and it was winter", in John 10:22–23. The Greek term that is used is "the renewals" (Greek ta engkainia τὰ ἐγκαίνια).[22] Josephus refers to the festival as "lights."[23]

Story

Background

Judea was part of the Ptolemaic Kingdom of Egypt until 200 BC when King Antiochus III the Great of Syria defeated King Ptolemy V Epiphanes of Egypt at the Battle of Panium. Judea then became part of the Seleucid Empire of Syria. King Antiochus III the Great wanting to conciliate his new Jewish subjects guaranteed their right to "live according to their ancestral customs" and to continue to practice their religion in the Temple of Jerusalem. However, in 175 BC, Antiochus IV Epiphanes, the son of Antiochus III, invaded Judea, ostensibly at the request of the sons of Tobias.[24] The Tobiads, who led the Hellenizing Jewish faction in Jerusalem, were expelled to Syria around 170 BC when the high priest Onias and his pro-Egyptian faction wrested control from them. The exiled Tobiads lobbied Antiochus IV Epiphanes to recapture Jerusalem. As the ancient Jewish historian Flavius Josephus tells us:

The king being thereto disposed beforehand, complied with them, and came upon the Jews with a great army, and took their city by force, and slew a great multitude of those that favored Ptolemy, and sent out his soldiers to plunder them without mercy. He also spoiled the temple, and put a stop to the constant practice of offering a daily sacrifice of expiation for three years and six months.

Traditional view

When the Second Temple in Jerusalem was looted and services stopped, Judaism was outlawed. In 167 BC Antiochus ordered an altar to Zeus erected in the Temple. He banned brit milah (circumcision) and ordered pigs to be sacrificed at the altar of the temple .[25]

Antiochus's actions provoked a large-scale revolt. Mattathias (Mattityahu), a Jewish priest, and his five sons Jochanan, Simeon, Eleazar, Jonathan, and Judah led a rebellion against Antiochus starting with Mattathias killing in his unbridled zeal first a Jew who wants to comply with Antiochus's order to sacrifice to Zeus and then the Greek official who is to enforce the government's behest (1 Mac. 2, 24-25[26]). Judah became known as Yehuda HaMakabi ("Judah the Hammer"). By 166 BC Mattathias had died, and Judah took his place as leader. By 165 BC the Jewish revolt against the Seleucid monarchy was successful. The Temple was liberated and rededicated. The festival of Hanukkah was instituted to celebrate this event.[27] Judah ordered the Temple to be cleansed, a new altar to be built in place of the polluted one and new holy vessels to be made. According to the Talmud, unadulterated and undefiled pure olive oil with the seal of the kohen gadol (high priest) was needed for the menorah in the Temple, which was required to burn throughout the night every night. The story goes that one flask was found with only enough oil to burn for one day, yet it burned for eight days, the time needed to prepare a fresh supply of kosher oil for the menorah. An eight-day festival was declared by the Jewish sages to commemorate this miracle.

The version of the story in 1 Maccabees states that an eight-day celebration of songs and sacrifices was proclaimed upon re-dedication of the altar, and makes no specific mention of the miracle of the oil.[28]

Academic sources

Some modern scholars argue that the king was intervening in an internal civil war between the Maccabean Jews and the Hellenized Jews in Jerusalem.[29][30][31][32]

These competed violently over who would be the High Priest, with traditionalists with Hebrew/Aramaic names like Onias contesting with Hellenizing High Priests with Greek names like Jason and Menelaus.[33] In particular Jason's Hellenistic reforms would prove to be a decisive factor leading to eventual conflict within the ranks of Judaism.[34] Other authors point to possible socioeconomic reasons in addition to the religious reasons behind the civil war.[35]

What began in many respects as a civil war escalated when the Hellenistic kingdom of Syria sided with the Hellenizing Jews in their conflict with the traditionalists.[36] As the conflict escalated, Antiochus took the side of the Hellenizers by prohibiting the religious practices the traditionalists had rallied around. This may explain why the king, in a total departure from Seleucid practice in all other places and times, banned a traditional religion.[37]

The miracle of the oil is widely regarded as a legend and its authenticity has been questioned since the Middle Ages.[38] However, by virtue of the famous question Rabbi Yosef Karo posed concerning why Hanukah is celebrated for eight days when the miracle was only for seven days (since there was enough oil for one day), it was clear that he believed it was a historical event, and this belief has been adopted by most of Orthodox Judaism, inasmuch as Rabbi Karo's Shulchan Aruch is a main Code of Jewish Law.

Characters and heroes

- Matisyahu the High Priest, also referred to as Mattathias and Mattathias ben Johanan. Matisyahu was a Jewish High Priest, who together with his five sons, played a central role in the story of Hanukkah.

- Judah the Maccabee, also referred to as Judas Maccabeus and Y'hudhah HaMakabi. Judah was the eldest son of Matisyahu and is acclaimed as one of the greatest warriors in Jewish history alongside Joshua, Gideon, and David.

- Eleazar the Maccabee, also referred to as Eleazar Avaran, Eleazar Maccabeus and Eleazar Hachorani/Choran.

- Simon the Maccabee, also referred to as Simon Maccabeus and Simon Thassi.

- Johanan the Maccabee, also referred to as Johanan Maccabeus and John Gaddi.

- Jonathan the Maccabee, also referred to as Jonathan Apphus.

- Antiochus IV Epiphanes.

- Judith. Acclaimed for her heroism in the assassination of Holofernes.

- Hannah and her seven sons. Arrested, tortured and killed one by one, by Antiochus IV Epiphanes for refusing to bow to an idol.

Rituals

Hanukkah is celebrated with a series of rituals that are performed every day throughout the 8-day holiday, some are family-based and others communal. There are special additions to the daily prayer service, and a section is added to the blessing after meals.

Hanukkah is not a "Sabbath-like" holiday, and there is no obligation to refrain from activities that are forbidden on the Sabbath, as specified in the Shulkhan Arukh.[39] Adherents go to work as usual, but may leave early in order to be home to kindle the lights at nightfall. There is no religious reason for schools to be closed, although, in Israel, schools close from the second day for the whole week of Hanukkah. Many families exchange gifts each night, such as books or games and "Hanukkah Gelt" is often given to children. Fried foods (such as latkes potato pancakes, jelly doughnuts sufganiyot and Sephardic Bimuelos) are eaten to commemorate the importance of oil during the celebration of Hanukkah. Some also have a custom to eat dairy products to remember Judith and how she overcame Holofernes by feeding him cheese, which made him thirsty, and giving him wine to drink. When Holofernes became very drunk, Judith cut off his head.

Kindling the Hanukkah lights

Each night, throughout the 8 day holiday, a candle or oil-based light, is lit. As a universally practiced "beautification" (hiddur mitzvah) of the mitzvah, the number of lights lit is increased by one each night.[40] An extra light called a shamash, meaning "attendant" or "sexton,"[1] is also lit each night, and is given a distinct location, usually higher, lower, or to the side of the others. While linguistically incorrect, the word shamus (Yiddish slang for "police" or "private investigator") has often been used as a reference to the extra candle.

The purpose of the extra light is to adhere to the prohibition, specified in the Talmud (Tracate Shabbat 21b–23a), against using the Hanukkah lights for anything other than publicizing and meditating on the Hanukkah miracle. This differs from Sabbath candles which are meant to be used for illumination and lighting. Hence, if one were to need extra illumination on Hanukkah, the shamash candle would be available, and one would avoid using the prohibited lights. Some, especially Ashkenazim, light the shamash candle first and then use it to light the others.[41] So altogether, including the shamash, two lights are lit on the first night, three on the second and so on, ending with nine on the last night, for a total of 44 (36, excluding the shamash). It is Sephardic custom not to light the shamash first and use it to light the rest. Instead, the shamash candle is the last to be lit, and a different candle or a match is used to light all the candles. Some Hasidic Jews follow this Sephardic custom as well.

The lights can be candles or oil lamps.[41] Electric lights are sometimes used and are acceptable in places where open flame is not permitted, such as a hospital room, or for the very elderly and infirm, however those who permit reciting a blessing over electric lamps only allow it if it is incandescent and battery operated (an incandescent flashlight would be acceptable for this purpose), however a blessing may not be recited over a plug-in menorah or lamp. Most Jewish homes have a special candelabrum referred to as either a Chanukiah (the Sephardi and Israeli term), or a menorah (the traditional Ashkenazi name); Many families use an oil lamp (traditionally filled with olive oil) for Hanukkah. Like the candle Chanukiah, it has eight wicks to light plus the additional shamash light. Since the 1970s the worldwide Chabad Hasidic movement has initiated public menorah lightings in open public places in many countries.[42]

The reason for the Hanukkah lights is not for the "lighting of the house within", but rather for the "illumination of the house without," so that passersby should see it and be reminded of the holiday's miracle (i.e. the triumph of the few over the many and of the pure over the impure). Accordingly, lamps are set up at a prominent window or near the door leading to the street. It is customary amongst some Ashkenazi Jews to have a separate menorah for each family member (customs vary), whereas most Sephardi Jews light one for the whole household. Only when there was danger of antisemitic persecution were lamps supposed to be hidden from public view, as was the case in Persia under the rule of the Zoroastrians, or in parts of Europe before and during World War II. However, most Hasidic groups light lamps near an inside doorway, not necessarily in public view. According to this tradition, the lamps are placed on the opposite side from the mezuzah, so that when one passes through the door s/he is surrounded by the holiness of mitzvot (the commandments).

Generally women are exempt in Jewish law from time-bound positive commandments, although the Talmud requires that women engage in the mitzvah of lighting Hanukkah candles “for they too were involved in the miracle.”[43] In practice, only the male members of Orthodox households are obliged to light the menorah. In practice, some Sephardi households involve everyone in the candle lighting, with the head of the household lighting the first candle each night, the wife the second candle, and the children, eldest first, lighting the subsequent candles.

The Menorah is also lit in synagogue between Minchah and Maariv prayers, with the blessings, to publicize the miracle. However, it also must be lit at home, and even the one who recited the blessings in the synagogue must recite the blessings again at home. For this reason, some congregations, particularly in certain Hasidic communities, have a custom to throw things, such as towels, at whoever lights the menorah in synagogue, to show that he must light again at home. But when a Rebbe lights in the synagogue before eating a meal there with the congregation, no towels are thrown. Some people disagree with the custom of throwing towels, as they see it as disrespectful to the synagogue, but it was the practice among many Hasidic masters.

The Menorah is also lit in the day time in synagogue during the Shacharith prayers, but no blessings are recited, and towels are not thrown.

Candle-lighting time

Hanukkah lights should usually burn for at least half an hour after it gets dark. The custom of the Vilna Gaon observed by many residents of Jerusalem as the custom of the city, is to light at sundown, although most Hasidim light later, even in Jerusalem. Many Hasidic Rebbes light much later to fulfill the obligation of publicizing the miracle by the presence of their Hasidim when they kindle the lights.[citation needed]

Inexpensive small wax candles sold for Hanukkah burn for approximately half an hour, so on most days this requirement can be safely ignored.

Friday night presents a problem, however. Since candles may not be lit on Shabbat itself, the candles must be lit before sunset. However, they must remain lit through the lighting of the Shabbat candles. In keeping with the above-stated prohibition, the Hanukkah menorah is lit first, followed by the special candles which signify the beginning of Shabbat.

Blessings over the candles

Typically three blessings (brachot; singular: brachah) are recited during this eight-day festival when lighting the candles:

On the first night of Hanukkah, Jews recite all three blessings; on all subsequent nights, they recite only the first two.[44]

The blessings are said before or after the candles are lit depending on tradition. On the first night of Hanukkah one light (candle or oil) is lit on the right side of the menorah, on the following night a second light is placed to the left of the first but it is lit first, and so on, proceeding from placing candles right to left but lighting them from left to right over the eight nights.

For the full text of the blessings, see List of Jewish prayers and blessings: Hanukkah.

Hanerot Halalu

After the lights are kindled the hymn Hanerot Halalu is recited. There are several different versions; the version presented here is recited in many Ashkenazic communities:[45]

| Hebrew | Transliteration | English |

|---|---|---|

הנרות הללו שאנו מדליקין על הנסים ועל הנפלאות ועל התשועות ועל המלחמות שעשית לאבותינו בימים ההם, בזמן הזה על ידי כהניך הקדושים. וכל שמונת ימי חנוכה הנרות הללו קודש הם, ואין לנו רשות להשתמש בהם אלא להאיר אותם בלבד כדי להודות ולהלל לשמך הגדול על נסיך ועל נפלאותיך ועל ישועותיך.

|

Hanneirot hallalu she'anu madlikin 'al hannissim ve'al hanniflaot 'al hatteshu'ot ve'al hammilchamot she'asita laavoteinu bayyamim haheim, (u)bazzeman hazeh 'al yedei kohanekha hakkedoshim. Vekhol-shemonat yemei Hanukkah hanneirot hallalu kodesh heim, ve-ein lanu reshut lehishtammesh baheim ella lir'otam bilvad kedei lehodot ul'halleil leshimcha haggadol 'al nissekha ve'al nifleotekha ve'al yeshu'otekha. | We kindle these lights for the miracles and the wonders, for the redemption and the battles that you made for our forefathers, in those days at this season, through your holy priests. During all eight days of Hanukkah these lights are sacred, and we are not permitted to make ordinary use of them except for to look at them in order to express thanks and praise to Your great Name for Your miracles, Your wonders and Your salvations. |

Maoz Tzur

In the Ashkenazi tradition, each night after the lighting of the candles, the hymn Ma'oz Tzur is sung. The song contains six stanzas. The first and last deal with general themes of divine salvation, and the middle four deal with events of persecution in Jewish history, and praises God for survival despite these tragedies (the exodus from Egypt, the Babylonian captivity, the miracle of the holiday of Purim, the Hasmonean victory), and a longing for the days when Judea will finally triumph over Rome.

The song was composed in the thirteenth century by a poet only known through the acrostic found in the first letters of the original five stanzas of the song: Mordechai.. The familiar tune is most probably a derivation of a German Protestant church hymn or a popular folk song.[46]

Other customs

After lighting the candles and Ma'oz Tzur, singing other Hanukkah songs is customary in many Jewish homes. Some Hasidic and Sephardi Jews recite Psalms, such as Psalms 30, Psalms 67, and Psalms 91. In North America and in Israel it is common to exchange presents or give children presents at this time. In addition, many families encourage their children to give tzedakah (charity) in lieu of presents for themselves.

Special additions to daily prayers

An addition is made to the "hoda'ah" (thanksgiving) benediction in the Amidah (thrice-daily prayers), called Al ha-Nissim ("On/about the Miracles").[47] This addition refers to the victory achieved over the Syrians by the Hasmonean Mattathias and his sons.

"We thank You also for the miraculous deeds and for the redemption and for the mighty deeds and the saving acts wrought by You, as well as for the wars which You waged for our ancestors in ancient days at this season. In the days of the Hasmonean Mattathias, son of Johanan the high priest, and his sons, when the iniquitous Greco-Syrian kingdom rose up against Your people Israel, to make them forget Your Torah and to turn them away from the ordinances of Your will, then You in your abundant mercy rose up for them in the time of their trouble, pled their cause, executed judgment, avenged their wrong, and delivered the strong into the hands of the weak, the many into the hands of few, the impure into the hands of the pure, the wicked into the hands of the righteous, and insolent ones into the hands of those occupied with Your Torah. Both unto Yourself did you make a great and holy name in Thy world, and unto Your people did You achieve a great deliverance and redemption. Whereupon your children entered the sanctuary of Your house, cleansed Your temple, purified Your sanctuary, kindled lights in Your holy courts, and appointed these eight days of Hanukkah in order to give thanks and praises unto Your holy name."

Translation of Al ha-Nissim

The same prayer is added to the grace after meals. In addition, the Hallel (praise) (Psalms 113 - Psalms 118) are sung during each morning service and the Tachanun penitential prayers are omitted.

The Torah is read every day in the shacharit morning services in synagogue, on the first day beginning from Numbers 6:22 (according to some customs, Numbers 7:1), and the last day ending with Numbers 8:4. Since Hanukkah lasts eight days it includes at least one, and sometimes two, Jewish Sabbaths (Saturdays). The weekly Torah portion for the first Sabbath is almost always Miketz, telling of Joseph's dream and his enslavement in Egypt. The Haftarah reading for the first Sabbath Hanukkah is Zechariah 2:14 – Zechariah 4:7. When there is a second Sabbath on Hanukkah, the Haftarah reading is from 1Kings 7:40 - 1Kings 7:50.

The Hanukkah menorah is also kindled daily in the synagogue, at night with the blessings and in the morning without the blessings.

The menorah is not lit during Shabbat, but rather prior to the beginning of Shabbat as described above and not at all during the day. During the Middle Ages "Megillat Antiochus" was read in the Italian synagogues on Hanukkah just as the Book of Esther is read on Purim. It still forms part of the liturgy of the Yemenite Jews.[19]

Zot Hanukkah

The last day of Hanukkah is known as Zot Hanukkah, from the verse read on this day in the synagogue Numbers 7:84, Zot Hanukkat Hamizbe'ach: "This was the dedication of the altar"). According to the teachings of Kabbalah and Hasidism, this day is the final "seal" of the High Holiday season of Yom Kippur, and is considered a time to repent out of love for God. In this spirit, many Hasidic Jews wish each other Gmar chatimah tovah ("may you be sealed totally for good"), a traditional greeting for the Yom Kippur season. It is taught in Hasidic and Kabbalistic literature that this day is particularly auspicious for the fulfillment of prayers.

Other related laws and customs

It is customary for women not to work for at least the first half hour of the candles' burning, and some have the custom not to work for the entire time of burning. It is also forbidden to fast or to eulogize during Hanukkah.[48]

Customs

Music

A large number of songs have been written on Hanukkah themes, perhaps more so than for any other Jewish holiday. Some of the best known are "Maoz Tzur" (Rock of Ages), "Latke'le Latke'le" (Yiddish song about cooking Latkes), "Hanukkiah Li Yesh" ("I Have a Hanukkah Menorah"), "Ocho Kandelikas" ("Eight Little Candles"), "Kad Katan" ("A Small Jug"), "S'vivon Sov Sov Sov" ("Dreidel, Spin and Spin"), Haneirot Halolu" ("These Candles which we light"), "Mi Yimalel" ("Who can Retell") and "Ner Li, Ner Li" ("I have a Candle"). The most well known in English-speaking countries include "Dreidel, Dreidel, Dreidel" and "Chanukah, Oh Chanukah".

Among the Rebbes of the Nadvorna Hasidic dynasty, it is customary for the Rebbes to play violin after the menorah is lit.

Penina Moise's Hannukah Hymn published in the 1842 Hymns Written for the Use of Hebrew Congregations was instrumental in the beginning of Americanization of Hanukkah.[6][49][50]

Foods

There is a custom of eating foods fried or baked in oil (preferably olive oil) to commemorate the miracle of a small flask of oil keeping the flame that was in the temple alight for eight days. Traditional foods include potato pancakes, known as latkes in Yiddish, especially among Ashkenazi families. Sephardi, Polish and Israeli families eat jam-filled doughnuts (Template:Lang-yi pontshkes), bimuelos (fritters) and sufganiyot which are deep-fried in oil. Hungarian Jews eat cheese pancakes known as "cheese latkes".

Bakeries in Israel have popularized many new types of fillings for sufganiyot besides the traditional strawberry jelly filling, including chocolate cream, vanilla cream, caramel, cappuccino and others.[51] In recent years, downsized, "mini" sufganiyot containing half the calories of the regular, 400-to-600-calorie version, have become popular.[52]

Rabbinic literature also records a tradition of eating cheese and other dairy products during Hanukkah.[53] This custom, as mentioned above, commemorates the heroism of Judith during the Babylonian captivity of the Jews and reminds us that women also played an important role in the events of Hanukkah.[54]

Dreidel

The dreidel, or sevivon in Hebrew, is a four-sided spinning top that children play with during Hanukkah. Each side is imprinted with a Hebrew letter. These letters are an abbreviation for the Hebrew words נס גדול היה שם (Nes Gadol Haya Sham, "A great miracle happened there"), referring to the miracle of the oil that took place in the Beit Hamikdash.

On dreidels sold in Israel, the fourth side is inscribed with the letter פ (Pe), rendering the acronym נס גדול היה פה (Nes Gadol Haya Po, "A great miracle happened here"), referring to the fact that the miracle occurred in the land of Israel, although this is a relatively recent innovation. Stores in Haredi neighborhoods sell the traditional Shin dreidels as well, because they understand "there" to refer to the Temple and not the entire Land of Israel, and because the Hasidic Masters ascribe significance to the traditional letters.

Some Jewish commentators ascribe symbolic significance to the markings on the dreidel. One commentary, for example, connects the four letters with the four exiles to which the nation of Israel was historically subject: Babylonia, Persia, Greece, and Rome.[55]

After lighting the Hanukkah menorah, it is customary in many homes to play the dreidel game: Each player starts out with 10 or 15 coins (real or of chocolate), nuts, raisins, candies or other markers, and places one marker in the "pot." The first player spins the dreidel, and depending on which side the dreidel falls on, either wins a marker from the pot or gives up part of his stash. The code (based on a Yiddish version of the game) is as follows:

- Nun–nisht, "nothing"–nothing happens and the next player spins

- Gimel–gants, "all"–the player takes the entire pot

- Hey–halb, "half"–the player takes half of the pot. If there are an odd number of markers, usually the player takes the extra one too.

- Shin–shtel ayn, "put in"–the player puts one marker in the pot

Another version differs:

- Nun–nem, "take"–the player takes one from the pot

- Gimel–gib, "give"–the player puts one in the pot

- Hey–halb, "half"–the player takes half of the pot

- Shin–shtil, "still" (as in "stillness")–nothing happens and the next player spins

The game may last until one person has won everything.

Tradition has it that the reason the dreidel game is played is to commemorate a game devised by the Jews to camouflage the fact that they were studying Torah, which was outlawed by the Seleucids. The Jews would gather in caves to study, posting a lookout to alert the group to the presence of Seleucid soldiers. If soldiers were spotted, the Jews would hide their scrolls and spin tops, so the Seleucids thought they were gambling, not learning.[56]

The historical context may be from the time of the Bar-Kohba war, 132-135 C.E. when the penalty for teaching Torah was death, so decreed by Rome. Others trace the dreidel itself to the children's top game Teetotum.[57] However, the dreidel game as we know it arose among the Ashkenazim. It is not a Sephardi tradition, though, of course, just like the singing of Maos Tzur, it has been adopted by other, non-Ashkenazi families.

- Dreidel gelt (dreidel money): The Eastern European game of dreidel (including the letters nun, gimmel, hey, shin) is like the German equivalent of the totum game: N = Nichts = nothing; G = Ganz = all; H = Halb = half; and S = Stell ein = put in. In German, the spinning top was called a "torrel" or "trundl," and in Yiddish it was called a "dreidel," a "fargl," a "varfl" [= something thrown], "shtel ein" [= put in], and "gor, gorin" [= all]. When Hebrew was revived as a spoken language, the dreidel was called, among other names, a sevivon, which is the one that caught on.

Some Hasidic Rebbes may play the dreidel game at their Tish, and often spiritual significance is attributed to this practice.

Some Hasidic children play with regular spinning tops on Hanukah, and also call them by the Yiddish name "dreidel".

Gelt

Chanukkah gelt (Yiddish for "money") known as dmei Hanukkah in Israel, is often distributed to children during the festival of Hanukkah. The giving of Hanukkah gelt also adds to the holiday excitement. The amount is usually in small coins, although grandparents or relatives may give larger sums. The tradition of giving Chanukah gelt dates back to a long-standing East European custom of children presenting their teachers with a small sum of money at this time of year as a token of gratitude. A number of additional reasons are given for this custom.[58]

- The Talmud states that the Hanukkah lights are sacred and may not be used for any other purpose. The Talmud cites that one may not count money by the candlelight. Giving out Hanukkah gelt — and not counting it near the menorah — is a way to remember and exercise this rule.[59]

- When discussing what a poor man is to do if he does not have enough money to purchase both Hanukkah candles and kiddush wine, the Talmud states that Hanukkah lights take precedence because they serve to publicize the miracle. The custom of giving Hanukkah gelt enabled the poor to get the money they needed for candles without feeling shame.[60]

- According to Magen Avraham (Abraham Abele Gombiner 1635–1682), poor yeshiva students would also receive a gift of money from their Jewish benefactors on Hanukkah.[61]

- According to Maimonides, the Greeks invaded the possessions of Israel in the same spirit in which they defiled the oil in the Holy Temple. They did not destroy the oil; they defiled it. They did not rob the Jewish people; they attempted to infuse their possessions with Greek ideals, so that they be used for egotistical and ungodly purposes, rather than for holy pursuits. Hanukkah gelt celebrates the freedom and mandate to channel material wealth toward spiritual ends.[62]

- In Hebrew, the words "Hanukkah" (dedication) and "hinnukh" (education) come from the same root.[63] Appropriately, during Hanukkah it is customary to give gelt to children as a reward for Torah study.[59]

In time, money was also given to children to keep for themselves. In the 1920s, American chocolatiers picked up on the gift/coin concept by creating chocolate gelt.[63]

Today, many Hasidic Rebbes also distribute coins to those who visit them during Hanukkah. Hasidic Jews consider this to be a segulah (merit / good luck) for success.

Symbolic importance

This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2014) |

Many people define major Jewish holidays as those that feature traditional holiday meals, kiddush, holiday candle-lighting, etc., and when all forms of work are forbidden. Only biblical holidays fit these criteria, and Chanukah was instituted some two centuries after the Bible was completed and canonized. Nevertheless, though Chanukah is of rabbinic origin, it is traditionally celebrated in a major and very public fashion. The requirement to position the menorah, or Hanukiah, at the door or window symbolizes the desire to give the Chanukah miracle a high profile.[64]

The classical rabbis downplayed the military and nationalistic dimensions of Hanukkah, and some even interpreted the emphasis upon the story of the miracle oil as a diversion away from the struggle with empires that had led to the disastrous downfall of Jerusalem to the Romans.[citation needed]

Some Jewish historians suggest a different explanation for the rabbinic reluctance to laud the militarism. First, the rabbis wrote after Hasmonean leaders had led Judea into Rome’s grip and so may not have wanted to offer the family much praise. Second, they clearly wanted to promote a sense of dependence on God, urging Jews to look toward the divine for protection. They likely feared inciting Jews to another revolt that might end in disaster, like the 135 C.E. experience.[65]

With the advent of Zionism and the state of Israel, however, these themes were reconsidered. In modern Israel, the national and military aspects of Hanukkah became, once again, more dominant.[citation needed]

In North America especially, Hanukkah gained increased importance with many Jewish families in the latter part of the 20th century, including among large numbers of secular Jews, who wanted a Jewish alternative to the Christmas celebrations that often overlap with Hanukkah.[citation needed] Though it was traditional among Ashkenazi Jews to give "gelt" or money to children during Hanukkah, in many families this has been supplemented with other gifts, so that Jewish children can enjoy gifts just as their Christmas-celebrating peers do.[citation needed]

While Hanukkah is a relatively minor Jewish holiday, as indicated by the lack of religious restrictions on work other than a few minutes after lighting the candles, in North America, Hanukkah in the 21st century has taken a place equal to Passover as a symbol of Jewish identity.[citation needed] Both the Israeli and North American versions of Hanukkah emphasize resistance, focusing on some combination of national liberation and religious freedom as the defining meaning of the holiday.[citation needed]

Judith and Holofernes

The eating of dairy foods, especially cheese, on Hanukkah is a minor custom that has its roots in the story of Judith. The deuterocanonical book of Judith (Yehudit or Yehudis in Hebrew), which is not part of the Tanakh, records that Holofernes, an Assyrian general, had surrounded the village of Bethulia as part of his campaign to conquer Judea.

After intense fighting, the water supply of the Jews was cut off and the situation became desperate. Judith, a pious widow, told the city leaders that she had a plan to save the city. Judith went to the Assyrian camps and pretended to surrender. She met Holofernes, who was smitten by her beauty. She went back to his tent with him, where she plied him with cheese and wine. When he fell into a drunken sleep, Judith beheaded him and escaped from the camp, taking the severed head with her (the beheading of Holofernes by Judith has historically been a popular theme in art).

When Holofernes' soldiers found his corpse, they were overcome with fear; the Jews, on the other hand, were emboldened, and launched a successful counterattack. The town was saved, and the Assyrians defeated.[66]

Alternative spellings

In Hebrew, the word Hanukkah is written Template:Hebrew or חנוכה (Ḥănukkāh). It is most commonly transliterated to English as Chanukah or Hanukkah, the former because the sound represented by "CH" ([χ], similar to the Scottish pronunciation of "loch") does not exist in the English language. Furthermore, the letter "ḥet" (ח), which is the first letter in the Hebrew spelling, is pronounced differently in modern Hebrew (voiceless uvular fricative) than in classical Hebrew (voiceless pharyngeal fricative [ħ]), and neither of those sounds is unambiguously representable in English spelling. Moreover, the 'kaf' consonant is geminate in classical (but not modern) Hebrew. Adapting the classical Hebrew pronunciation with the geminate and pharyngeal Ḥeth can lead to the spelling "Hanukkah"; while adapting the modern Hebrew pronunciation with no gemination and uvular Ḥeth leads to the spelling "Chanukah". It has also been spelled as "Hannukah".

Historic timeline

- 198 BCE: Armies of the Seleucid King Antiochus III (Antiochus the Great) oust Ptolemy V from Judea and Samaria.

- 175 BCE: Antiochus IV (Epiphanes) ascends the Seleucid throne.

- 168 BCE: Under the reign of Antiochus IV, the second Temple is looted, Jews are massacred, and Judaism is outlawed.

- 167 BCE: Antiochus orders an altar to Zeus erected in the Temple. Mattathias, and his five sons John, Simon, Eleazar, Jonathan, and Judah lead a rebellion against Antiochus. Judah becomes known as Judah Maccabee ("Judah the Hammer").

- 166 BCE: Mattathias dies, and Judah takes his place as leader. The Hasmonean Jewish Kingdom begins; It lasts until 63 BCE

- 165 BCE: The Jewish revolt against the Seleucid monarchy is successful in recapturing the Temple, which is liberated and rededicated (Hanukkah).

- 142 BCE: Re-establishment of the Second Jewish Commonwealth. The Seleucids recognize Jewish autonomy. The Seleucid kings have a formal overlordship, which the Hasmoneans acknowledged. This inaugurates a period of population growth, and religious, cultural and social development. This included the conquest of the areas now covered by Transjordan, Samaria, Galilee, and Idumea (also known as Edom), and the forced conversion of Idumeans to the Jewish religion, including circumcision.[67]

- 139 BCE: The Roman Senate recognizes Jewish autonomy.

- 134 BCE: Antiochus VII Sidetes besieges Jerusalem. The Jews under John Hyrcanus become Seleucid vassals, but retain religious autonomy.[68]

- 129 BCE: Antiochus VII dies.[69] The Hasmonean Jewish Kingdom throws off Syrian rule completely

- 96 BCE: An eight-year civil war begins.

- 83 BCE: Consolidation of the Kingdom in territory east of the Jordan River.

- 63 BCE: The Hasmonean Jewish Kingdom comes to an end because of rivalry between the brothers Aristobulus II and Hyrcanus II, both of whom appeal to the Roman Republic to intervene and settle the power struggle on their behalf. The Roman general Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (Pompey the Great) is dispatched to the area. 12 thousand Jews are massacred as Romans enter Jerusalem. The Priests of the Temple are struck down at the Altar. Rome annexes Judea.

Battles of the Maccabean revolt

Key battles between the Maccabees and the Seleucid Syrian-Greeks:

- Battle of Adasa (Judas Maccabeus leads the Jews to victory against the forces of Nicanor.)

- Battle of Beth Horon (Judas Maccabeus defeats the forces of Seron.)

- Battle of Beth-zechariah (Elazar the Maccabee is killed in battle. Lysias has success in battle against the Maccabess, but allows them temporary freedom of worship.)

- Battle of Beth Zur (Judas Maccabeus defeats the army of Lysias, recapturing Jerusalem.)

- Dathema (A Jewish fortress saved by Judas Maccabeus.)

- Battle of Elasa (Judas Maccabeus dies in battle against the army of King Demetrius and Bacchides. He is succeeded by Jonathan Maccabaeus and Simon Maccabaeus who continue to lead the Jews in battle.)

- Battle of Emmaus (Judas Maccabeus fights the forces of Lysias and Georgias).

- Battle of Wadi Haramia.

Dates

The dates of Hanukkah are determined by the Hebrew calendar. Hanukkah begins at the 25th day of Kislev, and concludes on the 2nd or 3rd day of Tevet (Kislev can have 29 or 30 days). The Jewish day begins at sunset, whereas the Gregorian calendar begins the day at midnight. Hanukkah begins at sunset of the date listed.

- 27 November 2013

- 16 December 2014

- 6 December 2015

- 24 December 2016

- 12 December 2017

- 2 December 2018

- 22 December 2019

- 10 December 2020

In 2013, on 28 November, the American holiday of Thanksgiving fell during Hanukkah for only the third time since Thanksgiving was declared a national holiday by President Abraham Lincoln. The last time was 1899; and due to the Gregorian and Jewish calendars being slightly out of sync with each other, it will not happen again in the foreseeable future.[70] This convergence prompted the creation of the portmanteau neologism Thanksgivukkah.[71][72][73]

Hanukkah in the White House

The United States has a history of recognizing and celebrating Hanukkah in a number of ways.

The earliest Hanukkah link with the White House occurred in 1951, when Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion presented United States President Harry Truman with a Hanukkah Menorah. In 1979 president Jimmy Carter took part in the first public Hanukkah candle-lighting ceremony of the National Menorah held across the White House lawn. In 1989, President George H.W. Bush displayed a menorah in the White House. In 1993, President Bill Clinton invited a group of schoolchildren to the Oval Office for a small ceremony.[74]

The United States Postal Service has released several Hanukkah themed postage stamps. In 1996 the United States Postal Service (USPS) issued a 32 cent Hanukkah stamp as a joint issue with Israel.[75] In 2004 after 8 years of reissuing the menorah design, the USPS issued a dreidel design for the Hanukkah stamp. The dreidel design was used through 2008. In 2009 a Hanukkah stamp was issued with a design featured a photograph of a menorah with nine lit candles.

In 2001, President George W. Bush held an official Hanukkah reception in the White House in conjunction with the candle-lighting ceremony, and since then this ceremony has become an annual tradition attended by Jewish leaders from around the country. In 2008, George Bush linked the occasion to the 1951 gift by using that menorah for the ceremony, with a grandson of Ben-Gurion and a grandson of Truman lighting the candles.

In December 2014, two Hanukkah celebrations were held at the White House. The White House commissioned a menorah made by students at the Max Rayne school in Israel and invited two of its students to join U.S. President Barack Obama and First Lady Michelle Obama as they welcomed over 500 guests to the celebration. The students' school in Israel had been subjected to arson by extremists.[76] President Obama said these "students teach us an important lesson for this time in our history. The light of hope must outlast the fires of hate. That’s what the Hanukkah story teaches us. It’s what our young people can teach us— that one act of faith can make a miracle, that love is stronger than hate, that peace can triumph over conflict.”[77] Rabbi Angela Warnick Buchdahl, in leading prayers at the ceremony commented on the how special the scene was, asking the President if he believed America's founding fathers could possibly have pictured that a female Asian-American rabbi would one day be at the White House leading Jewish prayers in front of the African-American president.[78]

Green Hanukkah

Some Jews in North America and Israel have taken up environmental concerns in relation to Hanukkah's "miracle of the oil", emphasizing reflection on energy conservation and energy independence. An example of this is the Coalition on the Environment and Jewish Life's renewable energy campaign.[79][80][81]

Gallery

An entire room of Paris's Museum of Jewish Art and History is dedicated to Hanukkah, through an exceptional collection of Hanukkiyot, in a variety of shapes and designs, origins and periods. This panorama stands as a metaphor for the great diversity of Jewish customs throughout the world.

-

France, 14th century

-

France, 16th century

-

Germany, 17th century

-

Italy, 18th century

-

Poland, 18th century

-

France, 19th century

-

Europe, 19th century

-

Yemen, 20th century

-

Tunisia, 20th century

-

Israel, 20th century

See also

References

- ^ a b Gateway To The Holy Land: "Hanukkah." Retrieved on 3 September 2010

- ^ Joshua Eli Plaut, A Kosher Christmas: 'Tis the Season to be Jewish. Rutgers University Press, 2012. Page 167.

- ^ Jonathan D. Sarna, How Hanukkah Came To The White House. Forward, 2 December 2009.

- ^ Joseph Telushkin, Rebbe: The Life and Teachings of Menachem M. Schneerson, the Most Influential Rabbi in Modern History. HarperCollins, 2014. Page 269.

- ^ Menachem Posner, 40 Years Later: How the Chanukah Menorah Made It's Way to the Public sphere. 1 December 2014.

- ^ a b Ashton, Dianne (2013). Hanukkah in America: A History. NYU Press. p. 42–46. ISBN 9781479858958.

Throughout the nineteenth century some Jews tried various ways to adapt Judaism to American life. As they began looking for images to help understand and explain what a proper response to American Challenges might be, Hanukkah became ripe for reinvention. In Charleston, South Carolina, one group of Jews made Hanukkah into a time for serious religious reflexion that responded to their evangelical Protestant milieu...[Moise's] poem gave Hanukkah a place in the emerging religious style of American culture that was dominated by the language of individualism and personal conscience derived from both Protestantism and the Enlightenment. However, neither the Talmud nor the Shulchan Aruch identifies Hanukkah as a special occasion to ask for the forgiveness of sins.

- ^ "BBC - Schools - Religion - Judaism".

- ^ Being Jewish: The Spiritual and Cultural Practice of Judaism Today, By Ari L. Goldman, Simon and Schuster, pg141

- ^ Scherman, Nosson. "Origin of the Name Chanukah". Torah.org.

- ^ Ran Shabbat 9b (Template:PDFLink)

- ^ Orthodox Union, The Lights of Chanukah – Laws and Customs. 9 April 2014.

- ^ http://www.orthodoxchristian.info/pages/old_testament.html

- ^ Dolanksy, Shawna (23 December 2011). "The Truth(s) About Hanukkah". Huffington Post.

- ^ Yesod Hamishna Va'arichatah pp. 25–28 (Template:PDFLink)

- ^ "Jewishvirtuallibrary.org". Jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 25 December 2011.

- ^ Atenebris Adsole (25 December 2002). "Babylonian Talmud: Shabbath 21".

- ^ Perseus.tufts.edu, Jewish Antiquities xii. 7, § 7, #323

- ^ Zvieli, Benjamin. "The Scroll of Antiochus". Retrieved 28 January 2007.

- ^ a b "The Scroll Of The Hasmoneans". Archived from the original on 18 March 2007.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 28 May 2007 suggested (help) - ^ Saadia Gaon, Introduction to Sefer Ha-Iggaron (ed. Abraham Firkovich), Odessa 1868 (Hebrew); See also The Scroll of Antiochus and The Unknown Chanukah Megillah

- ^ Hubarah, Yosef. "Sefer Ha-Tiklāl (Tiklal Qadmonim)". Jerusalem 1964, pp. 75b–79b, s.v. מגלת בני חשמונאי (Hebrew).

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ This is the first reference to the Feast of Dedication by this name (ta egkainia, ta enkainia [a typical “festive plural”]) in Jewish literature (Hengel 1999: 317). "

- ^ Mercer Dictionary of the Bible ed. Watson E. Mills, Roger Aubrey Bullard – 1990 -"Hence Hanukkah also is called the Feast of Lights, an alternate title Josephus confirms with this rationale: "And from that time to this we celebrate this festival, and call it 'Lights.' I suppose the reason was, because this liberty beyond our hopes appeared to us; and that thence was the name given to that festival." (per The works of Flavius Josephus translated by William Whiston)

- ^ Old.perseus.tufts.edu Jewish War i. 31

- ^ Old.perseus.tufts.edu, Jewish War i. 34

- ^ http://www.earlyjewishwritings.com/text/1maccabees.html

- ^ "1 Macc. iv. 59". Archived from the original on 27 June 2004.

- ^ "1 Macc. iv. 36". Archived from the original on 16 January 2008.

- ^ Telushkin, Joseph (1991). Jewish Literacy: The Most Important Things to Know about the Jewish Religion, Its People, and Its History. W. Morrow. p. 114. ISBN 0-688-08506-7.

- ^ Johnston, Sarah Iles (2004). Religions of the Ancient World: A Guide. Harvard University Press. p. 186. ISBN 0-674-01517-7.

- ^ Greenberg, Irving (1993). The Jewish Way: Living the Holidays. Simon & Schuster. p. 29. ISBN 0-671-87303-2.

- ^ Schultz, Joseph P. (1981). Judaism and the Gentile Faiths: Comparative Studies in Religion. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. p. 155. ISBN 0-8386-1707-7.

Modern scholarship on the other hand considers the Maccabean revolt less as an uprising against foreign oppression than as a civil war between the orthodox and reformist parties in the Jewish camp

- ^ Gundry, Robert H. (2003). A Survey of the New Testament. Zondervan. p. 9. ISBN 0-310-23825-0.

- ^ Grabbe, Lester L. (2000). Judaic Religion in the Second Temple Period: Belief and Practice from the Exile to Yavneh. Routledge. p. 59. ISBN 0-415-21250-2.

- ^ Freedman, David Noel; Allen C. Myers; Astrid B. Beck (2000). Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 837. ISBN 0-8028-2400-5.

- ^ Wood, Leon James (1986). A Survey of Israel's History. Zondervan. p. 357. ISBN 0-310-34770-X.

- ^ Tcherikover, Victor (1999) [1959]. Hellenistic Civilization and the Jews. Baker Academic. ISBN 0-8010-4785-4.

- ^ Skolnik, Berenbaum,, Fred, Michael (2007). Encyclopaedia Judaica, Volume 9. Granite Hill Publishers, pg 332.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Shulkhan Arukh Orach Chayim 670:1

- ^ Shulkhan Arukh Orach Chayim 671:2

- ^ a b Shulkhan Arukh Orach Chayim 673:1

- ^ "JTA NEWS".

- ^ Babylonian Talmud: Shabbat 23a

- ^ Shulkhan Arukh Orach Chayim 676:1–2

- ^ Shulkhan Arukh Orach Chayim 676:4

- ^ [1]

- ^ Shulkhan Arukh Orach Chayim 682:1

- ^ "The Laws of Chanukah". Ohr Somayach.

- ^ The Post and Courier, Celebrating Hanukkah, Adam Parker, Dec 18 2011

- ^ Ashton, Dianne. "Quick to the Party: The Americanization of Hanukkah and Southern Jewry". Southern Jewish History. 12: 1–38.

- ^ Gur, Jana, The Book of New Israeli Food: A Culinary Journey, pp. 238–243, Schocken (2008) ISBN 0-8052-1224-8

- ^ Minsberg, Tali and Lidman, Melanie. Love Me Dough. Jerusalem Post, 10 December 2009. Retrieved 17 December 2009.

- ^ Benyamina Soloveitchik, Why All the Oil and Cheese?.

- ^ Yehudit: The Woman Who Saved the Day.

- ^ Yaakov, Rabbi. "Ohr Somayach :: Chanukah :: The Secret of the Dreidel". Ohr.org.il. Retrieved 25 December 2011.

- ^ Otzar Kol Minhagei Yeshurun 19:4

- ^ "parshablog: Why we should ban playing dreidel, pt ii". Parsha.blogspot.com. 28 December 2008. Retrieved 6 July 2013.

- ^ Why the Gelt? Reasons for giving Chanukah gifts

- ^ a b Likutei Levi Yitzchak, Igrot, p. 358.

- ^ Magen Avraham, preface to Orach Chaim 670.

- ^ The Biblical and Historical Background of Jewish Customs and Ceremonies by Abraham P. Bloch. Published by KTAV Publishing House, Inc., 1980. Pp. 277.

- ^ Likutei Sichot, vol. 10, p. 291.

- ^ a b "Deconstructing Chocolate Gelt". Forward.com. Retrieved 25 December 2011.

- ^ Is Hanukkah a major Jewish Holiday?

- ^ Dianne Ashton, Hanukkah in America: A History, New York: New York University Press, 2013; pg. 29.

- ^ Mishna Berurah 670:2:10

- ^ Josephus, Ant. xiii, 9:1., via

- ^ Smith, Mahlon H. "Antiochus VII Sidetes".

- ^ Ginzburg, Louis (1901). "Antiochus VII., Sidetes". Jewish Encyclopedia.

- ^ Hoffman, Joel (24 November 2013). "Why Hanukkah and Thanksgiving Will Never Again Coincide". Huffington Post. Retrieved 2 December 2013.

- ^ Amy Spiro (17 November 2013). "Thanksgivukka: Please pass the turkey-stuffed doughnuts". Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 22 November 2013.

- ^ Christine Byrne (2 October 2013). "How To Celebrate Thanksgivukkah, The Best Holiday Of All Time". Buzzfeed. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- ^ Stu Bykofsky (22 October 2012). "Thanks for Thanukkah!". Philly.com. Retrieved 11 October 2013.

- ^ "How Hanukkah Came to the White House". The Jewish Daily Forward. 2 December 2009.

- ^ "Israeli-American Hanukkah Stamp". Mfa.gov.il. 22 October 1996. Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- ^ "'Jerusalem school hit by arson creates menorah used at White House Hanukka event' (19 Dec 2014) jerusalem Post" http://www.jpost.com/International/Jerusalem-school-hit-by-arson-attack-creates-menorah-for-White-House-Hanukka-event

- ^ "Arab-Jewish school's menorah lights up White House Hanukkah party | The Times of Israel" http://www.timesofisrael.com/hand-in-hand-schools-menorah-lights-up-white-house-hanukkah-party/

- ^ "jane Eisner 'A Most Inspiring Hanukkah at the White House' (18 Dec 2014) The Jewish Daily Forward" http://blogs.forward.com/forward-thinking/211168/a-most-inspiring-hanukkah-at-the-white-house/?

- ^ "Shalom Center on Hannukah and the environment". Theshalomcenter.org. 16 November 2007. Retrieved 25 December 2011.

- ^ Hoffman, Gil (4 December 2007). "Jerusalem Post: Green Hanukkia' campaign sparks ire". Fr.jpost.com. Retrieved 25 December 2011.

- ^ Dobb, Rabbi Fred Scherlinder (6 July 2011). "CFL Hannukah Installation ceremony". Coalition on Environment and Jewish Life (COEJL). Retrieved 28 November 2013.

Further reading

- Ashton, Dianne (2013). Hanukkah in America: A History. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-0739-5.