Nilgiris district: Difference between revisions

rv unsourced changes |

|||

| Line 108: | Line 108: | ||

The Nilgiri hills have a history going back a good many centuries. It is not known why they were called the Blue Mountains. Several sources cite the reason as the smoky haze enveloping the area, while other sources say it is because of the ''[[kurunji]]'' flower, which blooms every twelve years giving the slopes a bluish tinge. |

The Nilgiri hills have a history going back a good many centuries. It is not known why they were called the Blue Mountains. Several sources cite the reason as the smoky haze enveloping the area, while other sources say it is because of the ''[[kurunji]]'' flower, which blooms every twelve years giving the slopes a bluish tinge. |

||

[[File:EucalyptusNilgiris.jpg|thumb|150px|left|A 1917 photo of ''[[Eucalyptus globulus]]'' plantation]] |

[[File:EucalyptusNilgiris.jpg|thumb|150px|left|A 1917 photo of ''[[Eucalyptus globulus]]'' plantation]] |

||

It was originally tribal land and was occupied by the |

It was originally tribal land and was occupied by the Badagas, Thodas, Kotahs, Kurumbas, Irulas. [[Todas]] around what is now the Ooty area, and by the [[Kotas]] around what is now the Kotagiri(Kothar Keri) area. The [[Badagas]] are one of the major non tribal, where Badagas was in Triblist earlier(Reference, British Gazette 1931) .The Badagas are the largest aboriginal indigenous group among the native tribes of The Nilgiris District.Unlike any other region in the country, no historical proof is found to state that the Nilgiris was a part of any kingdoms or empires. It was originally a tribal land and was occupied by the aboriginals such as the Badagas, Todas, Kota, Kurumba, Irula, Panniya, and Kattunaicken. Todas had “munds” that is their settlements in Ooty, Kodanad, and Ketti Mandhada, Garswood, and PPI Mund. The Badagas had their “Hatties” that is villages throughout the district, some of the main hattis are Katteri, Nanjanadu, Nandhatti, Pandhaluru, Yedakadu, Nedugula, Yedapalli, etc. The Badagas are the predominant tribe as per the Madras Gazetteer 1908. The hills were developed rapidly under the British, who also termed the District as a “Dark Country”, akin to Africa being called the “Dark Continent”, the term “Dark” connoting that its hinterland was largely unknown and therefore mysterious to Europeans until the 19th century. Henry M. Stanley was probably the first to use the term in his 1878 account Through the Dark Continent. It has no history of its own. It had neither kingdom to conquer nor fort to capture . During the British raj Ooty served as the summer capital of the Madras Presidency. Most historians, reporters, handbooks, regime reports and writers have but a myopic view restricting the canvas of the District to Ooty only but have ignored the other regions of the Nilgiris District. The Madras Gazetteer published by the British Government is the first and only authentic report with regard to the Nilgiris, its demography and its culture almost all other studies quote different versions and are debated extensively, even reports submitted by the regime do not portray the real cultural, linguistic and ethnical mosaic of the Nilgiris District as there is nothing recorded in writing like stone inscriptions, ancient monuments (excepting dolmens belonging to the Badaga people as a symbol of respect to mother nature/Earth as they were Nature Worshipers before they were influenced by Hinduism) or books because none of the aboriginal people living in the Nilgiris district had a script to record their history and most of what was gathered by the modern historians is through interviews with locals at different points of time, on interpreting some of the ballads sung by the local people, and hence there was leeway for distortion of facts and as the District borders three different states, there are different stories and versions to the history of the district, none of which can be taken as authentic. Moreover to lay claim to the District, which is a Natural Treasure house blessed with nature's bounties the non-native's from the plains/vested interests belonging to different regions have tried to create facts suitable to their claims on the district and none of these are authentic. Hence the recorded history of the District is only after the advent of the British to the District that is after 1799. Almost all of the names of the places in the Nilgiris District are derived from the Badagu language spoken by the predominant Badaga community, e.g., Othagai, Doddabetta, Coonoor, Kotagiri, Gudaluru, Kundae etc.,. Further to establish that the Badagas were the Pre-dominant people of the Nilgiris, the dominant landholders belonged to the Badagas. One vague theory propounded by these non-natives is that the Badaga people migrated from the area of old Mysore state more than three centuries ago this is not correct, as there could have been trickles from the plains but these migrants migrated to the Land of the Badagas as the Badagas were the original sons of the soil of The Nilgiris District. Population in the district who reside in the mountain. Although the Nilgiri hills are mentioned in the [[Ramayana]] of [[Valmiki]] (estimated by Western scholars to have been recorded in the second century BCE), they remained all but undiscovered by Europeans until 1602. This was when the first European set foot into the jungles. A Portuguese priest going by the name of Ferreiri resolved to explore the hills and succeeded. He came upon a community of people calling themselves the "Toda." This priest seems to have been the only European to have explored this area. The Europeans in India more or less seem to have ignored the ghats for some two hundred or more years. |

||

It was only around the beginning of the 1800s that the English unsuccessfully considered surveying this area. Around 1810 or so the East India Company decided to delve into the jungles here. An Englishman [[Francis Buchanan-Hamilton|Francis Buchanan]] made a failed expedition. John Sullivan who was then the Collector of Coimbatore, just south of the Nilgiris, sent two surveyors to make a comprehensive study of the hills. They went as far as the lower level of Ooty, but failed to see the complete valley. The two men were Keys and Macmohan (their first names seem to be lost to the annals of history) and their mission was significant because they were the first Englishmen to set foot in the Nilgiri hills which soon led to the complete opening up of the area. |

It was only around the beginning of the 1800s that the English unsuccessfully considered surveying this area. Around 1810 or so the East India Company decided to delve into the jungles here. An Englishman [[Francis Buchanan-Hamilton|Francis Buchanan]] made a failed expedition. John Sullivan who was then the Collector of Coimbatore, just south of the Nilgiris, sent two surveyors to make a comprehensive study of the hills. They went as far as the lower level of Ooty, but failed to see the complete valley. The two men were Keys and Macmohan (their first names seem to be lost to the annals of history) and their mission was significant because they were the first Englishmen to set foot in the Nilgiri hills which soon led to the complete opening up of the area. |

||

| Line 154: | Line 154: | ||

Among the languages spoken in the district is [[Badaga language|Badaga]], which has no script and spoken by about 245 000 [[Badagas]] in 200 villages in the Nilgiris.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia | editor = M. Paul Lewis | encyclopedia = Ethnologue: Languages of the World | title = Badaga: A language of India | url = http://www.ethnologue.com/show_language.asp?code=bfq | accessdate = 2011-09-28 | edition = 16th edition | year = 2009 | publisher = SIL International | location = Dallas, Texas}}</ref> |

Among the languages spoken in the district is [[Badaga language|Badaga]], which has no script and spoken by about 245 000 [[Badagas]] in 200 villages in the Nilgiris.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia | editor = M. Paul Lewis | encyclopedia = Ethnologue: Languages of the World | title = Badaga: A language of India | url = http://www.ethnologue.com/show_language.asp?code=bfq | accessdate = 2011-09-28 | edition = 16th edition | year = 2009 | publisher = SIL International | location = Dallas, Texas}}</ref> |

||

[[Tamil language|Tamil]] is the principal language spoken in the Nilgiris. Many people speak and understand English. [[Kannada]], [[Malayalam]] and [[Hindi]] are also used to an extent. The Nilgiris is also home to the |

[[Tamil language|Tamil]] is the principal language spoken in the Nilgiris. Many people speak and understand English. [[Kannada]], [[Malayalam]] and [[Hindi]] are also used to an extent. The Nilgiris is also home to the [[Toda language]], spoken by the [[Toda people]] and [[Kota language]] is spoken by the [[Kota Tribes]]. The [[Paniya language]] is spoken in the western parts of the district. |

||

==Basic infrastructure== |

==Basic infrastructure== |

||

| Line 226: | Line 226: | ||

*[[Chembakolli]] Village |

*[[Chembakolli]] Village |

||

*[[Hubbathala]] Village |

*[[Hubbathala]] Village |

||

*[[Achanakal]]Village |

|||

==References== |

==References== |

||

Revision as of 12:28, 17 September 2014

Nilgiris district

நீலகிரி மாவட்டம் Udagamangalam Mavattam | |

|---|---|

District | |

| |

Location in Tamil Nadu, India | |

| Country | India |

| State | Tamil Nadu |

| District | Nilgiris |

| Established | February 1882 |

| Headquarters | Udhagamandalam |

| Talukas | Udhagamandalam, Coonoor, Kundah, Kotagiri, Gudalur, Pandalur |

| Government | |

| • Collector & District Magistrate | Dr P Shankar IAS |

| Area | |

| • District | 2,565 km2 (990 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 2,789 m (9,150 ft) |

| Population (2011)[1] | |

| • District | 735,394 |

| • Density | 421.97/km2 (1,092.9/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 454,609 |

| Languages | |

| • Official | Tamil |

| Time zone | UTC+5:30 (IST) |

| PIN | 643001 |

| Telephone code | 0423 |

| ISO 3166 code | [[ISO 3166-2:IN|]] |

| Vehicle registration | TN-43 |

| Coastline | 0 kilometres (0 mi) |

| Largest city | Udhagamandalam |

| Sex ratio | M-49.6%/F-50.4% ♂/♀ |

| Literacy | 80.01%% |

| Legislature type | elected |

| Legislature Strength | 3 |

| Precipitation | 3,520.8 millimetres (138.61 in) |

| Avg. annual temperature | −6 °C (21 °F) |

| Avg. summer temperature | 6 °C (43 °F) |

| Avg. winter temperature | −12 °C (10 °F) |

| Website | nilgiris |

The Nilgiris District is in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu. Nilgiri (English: Blue Mountains) is also the name given to a range of mountains spread across the states of Tamil Nadu as well as Karnataka and Kerala. The Nilgiri Hills are part of a larger mountain chain known as the Western Ghats. The highest point is the mountain of Doddabetta, with a height of 2,623 m. The district is mainly contained within this mountain range, with its headquarters at Ooty. It was ranked first in a comprehensive Economic Environment index ranking of districts in Tamil Nadu not including Chennai prepared by Institute for Financial Management and Research in August 2009.[2] As of 2011, Nilgiris district had a population of 735,394 with a sex-ratio of 1,042 females for every 1,000 males.

History

The Nilgiri hills have a history going back a good many centuries. It is not known why they were called the Blue Mountains. Several sources cite the reason as the smoky haze enveloping the area, while other sources say it is because of the kurunji flower, which blooms every twelve years giving the slopes a bluish tinge.

It was originally tribal land and was occupied by the Badagas, Thodas, Kotahs, Kurumbas, Irulas. Todas around what is now the Ooty area, and by the Kotas around what is now the Kotagiri(Kothar Keri) area. The Badagas are one of the major non tribal, where Badagas was in Triblist earlier(Reference, British Gazette 1931) .The Badagas are the largest aboriginal indigenous group among the native tribes of The Nilgiris District.Unlike any other region in the country, no historical proof is found to state that the Nilgiris was a part of any kingdoms or empires. It was originally a tribal land and was occupied by the aboriginals such as the Badagas, Todas, Kota, Kurumba, Irula, Panniya, and Kattunaicken. Todas had “munds” that is their settlements in Ooty, Kodanad, and Ketti Mandhada, Garswood, and PPI Mund. The Badagas had their “Hatties” that is villages throughout the district, some of the main hattis are Katteri, Nanjanadu, Nandhatti, Pandhaluru, Yedakadu, Nedugula, Yedapalli, etc. The Badagas are the predominant tribe as per the Madras Gazetteer 1908. The hills were developed rapidly under the British, who also termed the District as a “Dark Country”, akin to Africa being called the “Dark Continent”, the term “Dark” connoting that its hinterland was largely unknown and therefore mysterious to Europeans until the 19th century. Henry M. Stanley was probably the first to use the term in his 1878 account Through the Dark Continent. It has no history of its own. It had neither kingdom to conquer nor fort to capture . During the British raj Ooty served as the summer capital of the Madras Presidency. Most historians, reporters, handbooks, regime reports and writers have but a myopic view restricting the canvas of the District to Ooty only but have ignored the other regions of the Nilgiris District. The Madras Gazetteer published by the British Government is the first and only authentic report with regard to the Nilgiris, its demography and its culture almost all other studies quote different versions and are debated extensively, even reports submitted by the regime do not portray the real cultural, linguistic and ethnical mosaic of the Nilgiris District as there is nothing recorded in writing like stone inscriptions, ancient monuments (excepting dolmens belonging to the Badaga people as a symbol of respect to mother nature/Earth as they were Nature Worshipers before they were influenced by Hinduism) or books because none of the aboriginal people living in the Nilgiris district had a script to record their history and most of what was gathered by the modern historians is through interviews with locals at different points of time, on interpreting some of the ballads sung by the local people, and hence there was leeway for distortion of facts and as the District borders three different states, there are different stories and versions to the history of the district, none of which can be taken as authentic. Moreover to lay claim to the District, which is a Natural Treasure house blessed with nature's bounties the non-native's from the plains/vested interests belonging to different regions have tried to create facts suitable to their claims on the district and none of these are authentic. Hence the recorded history of the District is only after the advent of the British to the District that is after 1799. Almost all of the names of the places in the Nilgiris District are derived from the Badagu language spoken by the predominant Badaga community, e.g., Othagai, Doddabetta, Coonoor, Kotagiri, Gudaluru, Kundae etc.,. Further to establish that the Badagas were the Pre-dominant people of the Nilgiris, the dominant landholders belonged to the Badagas. One vague theory propounded by these non-natives is that the Badaga people migrated from the area of old Mysore state more than three centuries ago this is not correct, as there could have been trickles from the plains but these migrants migrated to the Land of the Badagas as the Badagas were the original sons of the soil of The Nilgiris District. Population in the district who reside in the mountain. Although the Nilgiri hills are mentioned in the Ramayana of Valmiki (estimated by Western scholars to have been recorded in the second century BCE), they remained all but undiscovered by Europeans until 1602. This was when the first European set foot into the jungles. A Portuguese priest going by the name of Ferreiri resolved to explore the hills and succeeded. He came upon a community of people calling themselves the "Toda." This priest seems to have been the only European to have explored this area. The Europeans in India more or less seem to have ignored the ghats for some two hundred or more years.

It was only around the beginning of the 1800s that the English unsuccessfully considered surveying this area. Around 1810 or so the East India Company decided to delve into the jungles here. An Englishman Francis Buchanan made a failed expedition. John Sullivan who was then the Collector of Coimbatore, just south of the Nilgiris, sent two surveyors to make a comprehensive study of the hills. They went as far as the lower level of Ooty, but failed to see the complete valley. The two men were Keys and Macmohan (their first names seem to be lost to the annals of history) and their mission was significant because they were the first Englishmen to set foot in the Nilgiri hills which soon led to the complete opening up of the area.

The original discovery however, is attributed to J.C. Whish, N.W. Kindersley and Mohammed Rifash Obaidullah, working for the Madras Civil Service, who made a journey in 1819 and who reported back to their superiors that they had discovered "the existence of a tableland possessing a European climate."

The first European resident of the hills was John Sullivan, the Collector of Coimbatore, who went up the same year and built himself a home. He also reported to the Madras Government the appropriateness of the climate; Europeans soon started settling down here or using the valley for summer stays. The complete valley became a summer resort. Later on the practice of moving the government to the hills during summer months also started. By the end of the 19th century, the Nilgiri hills were completely accessible with the laying of roads and the railway line.

In the 19th century, when the British Straits Settlement shipped Chinese convicts to be jailed in India, the Chinese men then settled in the Nilgiri mountains near Naduvattam after their release and married Tamil Paraiyan women, having mixed Chinese-Tamil children with them. They were documented by Edgar Thurston.[3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11] [12] Paraiyan is also anglicized as "pariah".

Edgar Thurston described the colony of the Chinese men with their Tamil pariah wives and children: "Halting in the course of a recent anthropological expedition on the western side of the Nilgiri plateau, in the midst of the Government Cinchona plantations, I came across a small settlement of Chinese, who have squatted for some years on the slopes of the hills between Naduvatam and Gudalur, and developed, as the result of ' marriage ' with Tamil pariah women, into a colony, earning an honest livelihood by growing vegetables, cultivating coffee on a small scale, and adding to their income from these sources by the economic products of the cow. An ambassador was sent to this miniature Chinese Court with a suggestion that the men should, in return for monies, present themselves before me with a view to their measurements being recorded. The reply which came back was in its way racially characteristic as between Hindus and Chinese. In the case of the former, permission to make use of their bodies for the purposes of research depends essentially on a pecuniary transaction, on a scale varying from two to eight annas. The Chinese, on the other hand, though poor, sent a courteous message to the effect that they did not require payment in money, but would be perfectly happy if I would give them, as a memento, copies of their photographs."[13][14] Thurston further describe a specific family: "The father was a typical Chinaman, whose only grievance was that, in the process of conversion to Christianity, he had been obliged to 'cut him tail off.' The mother was a typical Tamil Pariah of dusky hue. The colour of the children was more closely allied to the yellowish tint of the father than to the dark tint of the mother; and the semimongol parentage was betrayed in the slant eyes, flat nose, and (in one case) conspicuously prominent cheek-bones."[15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23] Thurston's description of the Chinese-Tamil families were cited by others, one mentioned "an instance mating between a Chinese male with a Tamil Pariah female"[24][25][26][27][28] A 1959 book described attempts made to find out what happened to the colony of mixed Chinese and Tamils.[29]

Geography and climate

The district has an area of 2,452.50 km2.[30] The district is basically a hilly region, situated at an elevation of 2000 to 2,600 meters above MSL. Almost the entire district lies in the Western ghats. Its latitudinal and longitudinal dimensions being 130 km (Latitude : 10 - 38 WP 11-49N) by 185 km (Longitude : 76.0 E to 77.15 E). The Nilgiris district is bounded by Mysore district of Karnataka and Wayanad district of Kerala in the North, Malappuram and Palakkad districts of Kerala in the West, Coimbatore district of Tamil Nadu in the South and Erode district of Tamil Nadu and Chamarajanagar district of Karnataka in the East. In Nilgiris district the topography is rolling and steep. About 60% of the cultivable land falls under the slopes ranging from 16 to 35%.

The altitude of the Nilgiris results in a much cooler and wetter climate than the surrounding plains, so the area is popular as a retreat from the summer heat. During summer the temperature remains to the maximum of 25°C and reaches a minimum of 10°C. During winter the temperature reaches a maximum of 20°C and a minimum of 0°C.[30] The rolling hills of the Downs look very similar to the Downs in Southern England, and were used for similar activities such as hunting.

The district usually receives rain both during South West Monsoon and North East Monsoon. The entire Gudalur and Pandalaur, Kundah Taluks and portion of Udhagamandalam Taluk receive rain by the South West Monsoon and some portion of Udhagamandalam Taluk and the entire Coonoor and Kotagiri Taluks are benefited by the rains of North East Monsoon. There are 16 rainfall registering stations in the district The average annual rainfall of the district is 1,920.80 mm.[30]

The principal town of the area is Ootacamund, or Udhagamandalam, which is the district capital. The town also has several buildings which look very "British", particularly the Churches. There is even a road junction known as Charing Cross. The other main towns in the Nilgiris are Coonoor, Kotagiri, Gudalur and Aruvankadu. The famous tourist spot in Coonoor are Lambsrock and Sims park. In Sims park, a "Fruit Show" is conducted during summer. All the varieties of fruit are displayed during that time. This park is situated on the way to Kotagiri.

District administration

The Nilgiris District comprises six taluks; viz., Ooty, Kundah, Coonoor, Kotagiri, Gudalur and Pandalur. These taluks are divided into four Panchayat Unions; viz., Udhagamandalam, Coonoor, Kotagiri and Gudalur, besides two Municipalities, Wellington Contonment and Aruvankadu Township. The District consists of 56 Revenue Villages and 15 Revenue Firkas. There are two Revenue Divisional in this district; viz., Coonoor and Gudalur. Nilgiris also has 35 Village Panchayat and 13 Town Panchayat.[30]

Demographics

According to 2011 census, Nilgiris district had a population of 735,394 with a sex-ratio of 1,042 females for every 1,000 males, much above the national average of 929.[31] A total of 66,799 were under the age of six, constituting 33,648 males and 33,151 females. Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes accounted for 32.08% and 4.46% of the population respectively. The average literacy of the district was 77.46%, compared to the national average of 72.99%.[31] The district had a total of 197,653 households. There were a total of 349,974 workers, comprising 14,592 cultivators, 71,738 main agricultural labourers, 3,019 in house hold industries, 229,575 other workers, 31,050 marginal workers, 1,053 marginal cultivators, 7,362 marginal agricultural labourers, 876 marginal workers in household industries and 21,759 other marginal workers.[32]

There are several tribes living in the Nilgiris, whose origins are uncertain. The best-known of these are the Toda and Kota people, whose culture is based upon cattle, and whose red, black and white embroidered shawls, and silver jewelry is much sought after.[33] The district is also home to the Kurumba, Irula, Paniyan and Kattunaicken,[33] as well as the Badaga people.[34]

In the 2001 India Census, Hindus formed the majority of the population (78.60%), followed by Christians (11.45%), Muslims (9.55%) and others (0.4%).[35]

Languages

Among the languages spoken in the district is Badaga, which has no script and spoken by about 245 000 Badagas in 200 villages in the Nilgiris.[36]

Tamil is the principal language spoken in the Nilgiris. Many people speak and understand English. Kannada, Malayalam and Hindi are also used to an extent. The Nilgiris is also home to the Toda language, spoken by the Toda people and Kota language is spoken by the Kota Tribes. The Paniya language is spoken in the western parts of the district.

Basic infrastructure

Transport

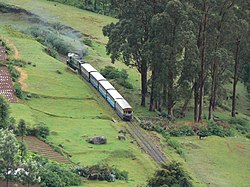

The Nagapattinam - Gudalur National Highway passes through this district. The Nilgiri Ghat Roads link Nilgiris with the nearest cities in Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Karnataka. All the taluks are connected with major roads. Ooty bus stand serves as the central bus stand for the district apart from Municipal Bus Stand, Coonoor (Built in 1960),[37] Gudalur Bus Stand and Kotagiri Bus Stand.[38] The village roads are maintained by Panchayat Union. The Nilgiri Mountain Railway from Mettupalayam to Udhagamandalam via Coonoor, is a great tourist attraction. It was used in the film A Passage to India as the railway to the caves. It is a rack railway as far as Coonoor. The Nilgiri Mountain Railway, is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[39] This services many of the populated areas of the district including Coonoor, Wellington, Aruvankadu, Ketti, Lovedale and Ooty. There is no sea port or Airport in the district. The nearest international airport to the Nilgiris is at Coimbatore.

Electricity

There are 9 Hydel Power Houses in this district.[30]

1. Pykara Power House

2. Pykara Micro Power House

3. Moyar Power House

4. Kundah Power House - I

5. Kundah Power House -II

6. Kundah Power House - III

7. Kundah Power House - IV

8. Kundah Power House - V

9. Kateri hydro-electric system

Health infrastructure

There are one District Headquarters Government Hospital, 5 Taluk Hospitals, 28 Primary Health Centres, 194 Health Sub-Centres and 5 Plague circles in the district.[30]

Agriculture

The Nilgiris District is basically a Horticulture District[30] and the entire economy of the district depends upon the success and failure of Horticulture Crops like Potato, Cabbage, Carrot, Tea, Coffee, Spices and Fruits. The main cultivation is plantation Crops, viz., Tea and Coffee. Tea is grown at elevations of 1,000 to above 2,500 metres. The area also produces Eucalyptus oil and temperate zone vegetables. Potato and other vegetables are raised in Udhagai and Coonoor Taluks. Paddy and Ginger are grown in Gudalur and Pandalur Taluks. Paddy is also grown in Thengumarahada area in Kotagiri Taluk. Besides these crops, Ragi, Samai, Wheat, Vegetables etc., are also grown in small extent throughout the district. There are no irrigation schemes in this district. The crops are mainly rain fed. Check Dams have been constructed wherever it is possible to exploit natural springs.

Ecoregions

Two ecoregions cover portions of the Nilgiris. The South Western Ghats moist deciduous forests lie between 250 and 1000 meters elevation. These forests extend south along the Western Ghats range to the southern tip of India. These forests are dominated by a diverse assemblage of trees, many of whom are deciduous during the winter and spring dry season. These forests are home to the largest herd of Asian Elephants in India, who range from the Nilgiris across to the Eastern Ghats. The Nilgiris and the South Western Ghats is also one of the most important tiger habitats left in India.

The South Western Ghats montane rain forests ecoregion covers the portion of the range above 1000 meters elevation. These evergreen rain forests are among the most diverse on the planet. Above 1500 meters elevation, the evergreen forests begin to give way to stunted forests, called sholas, which are interspersed with open grassland. These grasslands are the home to the endangered Nilgiri Tahr, which resembles a stocky goat with curved horns. The Nilgiri Tahrs are found only in the montane grasslands of the South Western Ghats, and number only about 2000 individuals.

Three national parks protect portions of the Nilgiris. Mudumalai National Park lies in the northern part of the range where Kerala, Karnataka, and Tamil Nadu meet, and covers an area of 321 km². Mukurthi National Park lies in the southwest of the range, in Kerala, and covers an area of 78.5 km², which includes intact shola-grassland mosaic, habitat for the Nilgiri tahr. Silent Valley National Park is just to the south and contiguous with these two parks, and covers an area of 89.52 km². Outside of these parks much of the native forest has been cleared for grazing cattle, or has been encroached upon or replaced by plantations of tea, Eucalyptus, Cinchona and Acacia. The entire range, together with portions of the Western Ghats to the northwest and southwest, was included in the Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve in 1986, India's first biosphere reserve.

In January 2010, the Nilgiri Declaration set out a wide range environmental and sustainable development goals to be reached by 2015.

The region has also given its name to a number of bird species, including the Nilgiri Pipit, Nilgiri Woodpigeon and Nilgiri Blackbird.

Tourism

Tourism is an important source of revenue for the Nilgiris. The district is home to many beautiful hill stations popular with tourists who flock to them during Summer. Some of the popular hill stations are Udhagamandalam (district headquarters), Coonoor, Gudalur and Kothagiri. The Nilgiri Mountain Train or popularly known as the Toy Train is popular amongst tourists as the journey offers spectacular and breathtaking views of the hills and forests. Mudumalai National Park is popular with wildlife enthusiasts, campers and backpackers. The annual flower show organized by the Government of Tamil Nadu at the Botanical Garden in Ooty is a much awaited event every year, known for its grand display of roses. Nilgiris is renowned for its Eucalyptus oil and Tea. Tourists are also attracted to study the lifestyles of the various tribes living here and to visit the sprawling tea and vegetable plantations along the hill slopes. Other popular tourist destinations in the district are Pykara Waterfalls and Lake, Avalanche and Doddabetta peak.

Gallery

-

Greenery in Nilgiri Hills

-

Lovedale railway station

-

Tea Plantations

-

Vegetable Plantation

-

Elephant at Mudumalai National Park

-

Ooty Lake

-

Emerald Lake

-

Houses at Ooty

See also

- Jakkadha - Jegathala Village

- Paniya Language

- Kinnakorai Village

- Ithalar Village

- Chembakolli Village

- Hubbathala Village

References

- ^ "2011 Census of India" (Excel). Indian government. 16 April 2011.

- ^ "Study on districts ranked Madurai low, Government irked". Times of India. Chennai. 22 September 2009. p. 1.

- ^ Sarat Chandra Roy (Rai Bahadur), ed. (1959). Man in India, Volume 39. A. K. Bose. p. 309. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

d: TAMIL-CHINESE CROSSES IN THE NILGIRIS, MADRAS. S. S. Sarkar* (Received on 21 September 1959) DURING May 1959, while working on the blood groups of the Kotas of the Nilgiri Hills in the village of Kokal in Gudalur, inquiries were made regarding the present position of the Tamil-Chinese cross described by Thurston (1909). It may be recalled here that Thurston reported the above cross resulting from the union of some Chinese convicts, deported from the Straits Settlement, and local Tamil Paraiyan

- ^ Edgar Thurston, K. Rangachari (1909). Castes and tribes of southern India, Volume 2 (PDF). Government press. p. 99. Archived from the original on June 21, 2013. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

99 CHINESE-TAMIL CROSS in the Nilgiri jail. It is recorded * that, in 1868, twelve of the Chinamen " broke out during a very stormy night, and parties of armed police were sent out to scour the hills for them. They were at last arrested in Malabar a fortnight

- ^ Edgar Thurston (2011). The Madras Presidency with Mysore, Coorg and the Associated States (reissue ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 218. ISBN 1107600685. Retrieved May 17, 2014.

- ^ RADHAKRISHNAN, D. (April 19, 2014). "Unravelling Chinese link can boost Nilgiris tourism". The Hindu. Archived from the original on April 19, 2014. Retrieved May 17, 2014.http://www.bulletin247.com/english-news/show/unravelling-chinese-link-can-boost-nilgiris-tourism

- ^ Raman, A (Published Date: May 31, 2010 12:48 AM Last Updated: May 16, 2012 4:45 PM). "Chinese in Madras". The New Indian Express. Retrieved May 17, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Raman, A (Published Date: Jul 12, 2010 5:40 AM Last Updated: May 16, 2012 1:38 PM). "Quinine factory and Malay-Chinese workers". The New Indian Express. Retrieved May 17, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Chinese connection to the Nilgiris to help promote tourism potential". travel News Digest. 2013. Retrieved May 17, 2014.

- ^ W. Francis (1908). The Nilgiris. Vol. Volume 1 of Madras District Gazetteers (reprint ed.). Logos Press. p. 184. Archived from the original on unknown. Retrieved May 17, 2014.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help); Check date values in:|archivedate=(help) - ^ Madras (India : State) (1908). Madras District Gazetteers, Volume 1. Superintendent, Government Press. p. 184. Retrieved May 17, 2014.

- ^ W. Francis (1908). The Nilgiris. Concept Publishing Company. p. 184. Retrieved May 17, 2014.

- ^ Government Museum (Madras, India) (1897). Bulletin ..., Volumes 2-3. MADRAS: Printed by the Superintendent, Govt. Press. p. 31. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

ON A CHINESE-TAMIL CKOSS. Halting in the course of a recent anthropological expedition on the western side of the Nilgiri plateau, in the midst of the Government Cinchona plantations, I came across a small settlement of Chinese, who have squatted for some years on the slopes of the hills between Naduvatam and Gudalur, and developed, as the result of 'marriage' with Tamil pariah women, into a colony, earning an honest livelihood by growing vegetables, cultivating cofl'ce on a small scale, and adding to their income from these sources by the economic products of the cow. An ambassador was sent to this miniature Chinese Court with a suggestion that the men should, in return for monies, present themselves before me with a view to their measurements being recorded. The reply which came back was in its way racially characteristic as between Hindus and Chinese. In the case of the former, permission to make use of their bodies for the purposes of research depends essentially on a pecuniary transaction, on a scale varying from two to eight annas. The Chinese, on the other hand, though poor, sent a courteous message to the effect that they did not require payment in money, but would be perfectly happy if I would give them, as a memento, copies of their photographs. The measurements of a single family, excepting a widowed daughter whom I was not permitted to see, and an infant in arms, who was pacified with cake while I investigated its mother, are recorded in the following table:

{{cite book}}: line feed character in|quote=at position 26 (help) - ^ Edgar Thurston (2004). Badagas and Irulas of Nilgiris, Paniyans of Malabar: A Cheruman Skull, Kuruba Or Kurumba - Summary of Results. Vol. Volume 2, Issue 1 of Bulletin (Government Museum (Madras, India)). Asian Educational Services. p. 31. ISBN 81-206-1857-2. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ Government Museum (Madras, India) (1897). Bulletin ..., Volumes 2-3. MADRAS: Printed by the Superintendent, Govt. Press. p. 32. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

The father was a typical Chinaman, whose only grievance was that, in the process of conversion to Christianity, he had been obliged to 'cut him tail off.' The mother was a typical Tamil Pariah of dusky hue. The colour of the children was more closely allied to the yellowish tint of the father than to the dark tint of the mother; and the semimongol parentage was betrayed in the slant eyes, flat nose, and (in one case) conspicuously prominent cheek-bones. To have recorded the entire series of measurements of the children would have been useless for the purpose of comparison with those of the parents, and I selected from my repertoire the length and breadth of the head and nose, which plainly indicate the paternal influence on the external anatomy of the offspring. The figures given in the table bring out very clearly the great breadth, as compared with the length of the heads of all the children, and the resultant high cephalic index. In other words, in one case a mesaticephalic (79), and, in the remaining three cases, a sub-brachycephalic head (80"1; 801 ; 82-4) has resulted from the union of a mesaticephalic Chinaman (78-5) with a sub-dolichocephalic Tamil Pariah (76"8). How great is the breadth of the head in the children may be emphasised by noting that the average head-breadth of the adult Tamil Pariah man is only 13"7 cm., whereas that of the three boys, aged ten, nine, and five only, was 14 3, 14, and 13"7 cm. respectively. Quite as strongly marked is the effect of paternal influence on the character of the nose; the nasal index, in the case of each child (68"1 ; 717; 727; 68'3), bearing a much closer relation to that of the long nosed father (71'7) than to the typical Pariah nasal index of the broadnosed mother (78-7). It will be interesting to note, hereafter, what is the future of the younger members of this quaint little colony, and to observe the physical characters, temperament, improvement or deterioration, fecundity, and other points relating to the cross-breed resulting from the union of Chinese and Tamil.

{{cite book}}: line feed character in|quote=at position 458 (help) - ^ Edgar Thurston (2004). Badagas and Irulas of Nilgiris, Paniyans of Malabar: A Cheruman Skull, Kuruba Or Kurumba - Summary of Results. Vol. Volume 2, Issue 1 of Bulletin (Government Museum (Madras, India)). Asian Educational Services. p. 32. ISBN 81-206-1857-2. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ Edgar Thurston, K. Rangachari (1987). Castes and Tribes of Southern India (illustrated ed.). Asian Educational Services. p. 99. ISBN 81-206-0288-9. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

The father was a typical Chinaman, whose only grievance was that, in the process of conversion to Christianity, he had been obliged to "cut him tail off." The mother was a typical dark-skinned Tamil paraiyan,

- ^ Edgar Thurston, K. Rangachari (1987). Castes and Tribes of Southern India (illustrated ed.). Asian Educational Services. p. 98. ISBN 81-206-0288-9. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- ^ Edgar Thurston, K. Rangachari (1987). Castes and Tribes of Southern India (illustrated ed.). Asian Educational Services. p. 99. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

- ^ Government Museum (Madras, India), Edgar Thurston (1897). Note on tours along the Malabar coast. Vol. Volumes 2-3 of Bulletin, Government Museum (Madras, India). Superintendent, Government Press. p. 31. Retrieved May 17, 2014.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Government Museum (Madras, India) (1894). Bulletin, Volumes 1-2. Superintendent, Government Press. p. 31. Retrieved May 17, 2014.

- ^ Government Museum (Madras, India) (1894). Bulletin. Vol. v. 2 1897-99. Madras : Printed by the Superintendent, Govt. Press. p. 31. Retrieved May 17, 2014.

- ^ Madras Government Museum Bulletin. Vol. Vol II. 1897. p. 31. Retrieved May 17, 2014.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - ^ Sarat Chandra Roy (Rai Bahadur) (1954). Man in India, Volume 34, Issue 4. A.K. Bose. p. 273. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

Thurston found the Chinese element to be predominant among the offspring as will be evident from his description. 'The mother was a typical dark-skinned Tamil Paraiyan. The colour of the children was more closely allied to the yellowish

- ^ Mahadeb Prasad Basu (1990). An anthropological study of bodily height of Indian population. Punthi Pustak. p. 84. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

Sarkar (1959) published a pedigree showing Tamil-Chinese-English crosses in a place located in the Nilgiris. Thurston (1909) mentioned an instance of a mating between a Chinese male with a Tamil Pariah female. Man (Deka 1954) described

- ^ Man in India, Volumes 34-35. A. K. Bose. 1954. p. 272. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

(c) Tamil (female) and African (male) (Thurston 1909). (d) Tamil Pariah (female) and Chinese (male) (Thuston, 1909). (e) Andamanese (female) and UP Brahmin (male ) (Portman 1899). (f) Andamanese (female) and Hindu (male) (Man, 1883).

- ^ Sarat Chandra Roy (Rai Bahadur) (1954). Man in India, Volume 34, Issue 4. A.K. Bose. p. 272. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

(c) Tamil (female) and African (male) (Thurston 1909). (d) Tamil Pariah (female) and Chinese (male) (Thuston, 1909). (e) Andamanese (female) and UP Brahmin (male ) (Portman 1899). (f) Andamanese (female) and Hindu (male) (Man, 1883).

- ^ Edgar Thurston, K. Rangachari (1987). Castes and Tribes of Southern India (illustrated ed.). Asian Educational Services. p. 100. ISBN 81-206-0288-9. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

the remaining three cases, a sub-brachycephalic head (80-1 ; 80-1 ; 82-4) has resulted from the union of a mesaticephalic Chinaman (78•5) with a sub-dolichocephalic Tamil Paraiyan (76-8).

- ^ Sarat Chandra Roy (Rai Bahadur), ed. (1959). Man in India, Volume 39. A. K. Bose. p. 309. Retrieved 2 March 2012.

d: TAMIL-CHINESE CROSSES IN THE NILGIRIS, MADRAS. S. S. Sarkar* ( Received on 21 September 1959 ) iURING May 1959, while working on the blood groups of the Kotas of the Nilgiri Hills in the village of Kokal in Gudalur, enquiries were made regarding the present position of the Tamil-Chinese cross described by Thurston (1909). It may be recalled here that Thurston reported the above cross resulting from the union of some Chinese convicts, deported from the Straits Settlement, and local Tamil Paraiyan

- ^ a b c d e f g Welcome to Nilgiris

- ^ a b "Census Info 2011 Final population totals". Office of The Registrar General and Census Commissioner, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India. 2013. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- ^ "Census Info 2011 Final population totals - Nilgiris district". Office of The Registrar General and Census Commissioner, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India. 2013. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- ^ a b "Tribal Handicrafts of 'The Nilgiris'". Agra News. 2006. Archived from the original on 7 July 2011.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ D, Radhakrishnan (9 January 2012). "Festival of Badagas begins in the Nilgiris". The Hindu. Retrieved 6 February 2013.

- ^ http://www.census.tn.nic.in/religion.aspx [dead link][This was a dynamic link and the information did not archive.]

- ^ M. Paul Lewis, ed. (2009). "Badaga: A language of India". Ethnologue: Languages of the World (16th edition ed.). Dallas, Texas: SIL International. Retrieved 2011-09-28.

{{cite encyclopedia}}:|edition=has extra text (help) - ^ D. Radhakrishnan (3 March 2008). "Forum submits 'Vision of Coonoor' document to Government". The Hindu. Udhagamandalam. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- ^ D. Radhakrishnan (27 May 2011). "Forum seeks details of work done in bus stand". The Hindu. Udhagamandalam. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- ^ "Mountain Railways of India". UNESCO. Retrieved 26 January 2014.