Venetian Lagoon: Difference between revisions

Citation bot (talk | contribs) Alter: template type. Add: pmid, pages, s2cid, doi. Formatted dashes. | You can use this bot yourself. Report bugs here. | Suggested by AManWithNoPlan | All pages linked from cached copy of User:AManWithNoPlan/sandbox2 | via #UCB_webform_linked 3125/3332 |

No edit summary Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

||

| (29 intermediate revisions by 23 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Enclosed bay in which the city of Venice is situated}} |

|||

{{Use dmy dates|date=October 2020}} |

{{Use dmy dates|date=October 2020}} |

||

{{Infobox body of water |

{{Infobox body of water |

||

| Line 36: | Line 37: | ||

| frozen = |

| frozen = |

||

| islands = |

| islands = |

||

| cities = [[Venice]], [[Campagna Lupia]], [[Cavallino-Treporti]], [[Chioggia]], [[Codevigo]], [[Jesolo]], [[Mira]], [[Musile di Piave]], [[Quarto d'Altino]], [[San Donà di Piave]] |

| cities = [[Venice]], [[Campagna Lupia]], [[Cavallino-Treporti]], [[Chioggia]], [[Codevigo]], [[Jesolo]], [[Mira, Veneto|Mira]], [[Musile di Piave]], [[Quarto d'Altino]], [[San Donà di Piave]] |

||

<!-- *** Website *** --> |

<!-- *** Website *** --> |

||

| website = |

| website = |

||

| Line 45: | Line 46: | ||

| designation1_offname = Laguna di Venezia: Valle Averto |

| designation1_offname = Laguna di Venezia: Valle Averto |

||

| designation1_date = 11 April 1989 |

| designation1_date = 11 April 1989 |

||

| designation1_number = 423<ref>{{Cite web|title=Laguna di Venezia: Valle Averto|website=[[Ramsar Convention|Ramsar]] Sites Information Service|url=https://rsis.ramsar.org/ris/423| |

| designation1_number = 423<ref>{{Cite web|title=Laguna di Venezia: Valle Averto|website=[[Ramsar Convention|Ramsar]] Sites Information Service|url=https://rsis.ramsar.org/ris/423|access-date=25 April 2018}}</ref>}} |

||

}} |

}} |

||

The '''Venetian Lagoon''' ({{lang-it|Laguna di Venezia}}; {{lang-vec|Łaguna de Venesia}}) is an enclosed bay of the [[Adriatic Sea]], in northern Italy, in which the city of [[Venice]] is situated. Its name in the [[Italian language|Italian]] and [[Venetian language |

The '''Venetian Lagoon''' ({{lang-it|Laguna di Venezia}}; {{lang-vec|Łaguna de Venesia}}) is an enclosed bay of the [[Adriatic Sea]], in [[northern Italy]], in which the city of [[Venice]] is situated. Its name in the [[Italian language|Italian]] and [[Venetian language]]s, ''{{lang|vec|Laguna Veneta}}'' (cognate of Latin ''{{lang|la|lacus}}'' {{gloss|lake}}), has provided the English name for an enclosed, shallow [[embayment]] of salt water: a [[lagoon]]. |

||

==Location== |

==Location== |

||

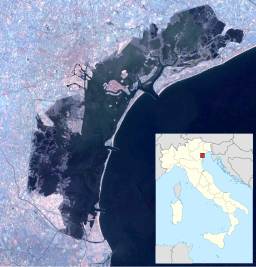

[[File:Venice Lagoon December 9 2001.jpg|thumb|left|The Venetian Lagoon]] |

[[File:Venice Lagoon December 9 2001.jpg|thumb|left|The Venetian Lagoon]] |

||

[[File:TorcelloLagune.jpg|thumb|left|The island of [[Torcello]] seen from the Lagoon at low tide]] |

[[File:TorcelloLagune.jpg|thumb|left|The island of [[Torcello]] seen from the Lagoon at low tide]] |

||

The Venetian Lagoon stretches from the [[River Sile]] in the north to the [[Brenta (river)|Brenta]] in the south, with a surface area of around {{convert|550|km2|sqmi|0|abbr=off}}. It is around 8% land, including Venice itself and many smaller islands. About 11% is permanently covered by open water, or [[canal]], as the network of dredged channels are called, while around 80% consists of [[mud flat]]s, tidal shallows and [[salt marsh]]es. The |

The Venetian Lagoon stretches from the [[River Sile]] in the north to the [[Brenta (river)|Brenta]] in the south, with a surface area of around {{convert|550|km2|sqmi|0|abbr=off}}. It is around 8% land, including Venice itself and many smaller islands. About 11% is permanently covered by open water, or [[canal]]s, as the network of dredged channels are called, while around 80% consists of [[mud flat]]s, tidal shallows and [[salt marsh]]es. The Lagoon is the largest [[wetland]] in the [[Mediterranean Basin]].<ref>{{cite news |author-link = Sylvia Poggioli |last = Poggioli |first = Sylvia |date = 7 January 2008 |url = https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=17855145 |title = MOSE Project Aims to Part Venice Floods |work = Morning Edition |type = Radio program |publisher = [[NPR]] }}</ref> |

||

It is connected to the [[Adriatic Sea]] by three [[inlet]]s: [[Lido di Venezia|Lido]], [[Malamocco]] and [[Chioggia]]. |

It is connected to the [[Adriatic Sea]] by three [[inlet]]s: [[Lido di Venezia|Lido]], [[Malamocco]] and [[Chioggia]]. Situated at one end of a largely enclosed sea, the lagoon is subject to large variations in its water level.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://earth.esa.int/web/earth-watching/landsat-25-years/landsat-5-showcase/cities/-/article/venice-italy-1985-2003-|title=Venice, Italy (1985–2003) - 25 Years of Landsat 5 - Landsat 5 showcase - Earth Watching|website=earth.esa.int|access-date=2019-02-01}}</ref> The most extreme are the [[spring tide]]s known as the ''{{lang|it|[[Acqua Alta|acqua alta]]}}'' (Italian for "high water"), which regularly flood much of Venice. |

||

The nearby [[Marano lagoon|Marano-Grado Lagoon]], with a surface area of around {{convert|160|km2|sqmi|0|abbr=off}}, is the northernmost lagoon in the Adriatic Sea and is |

The nearby [[Marano lagoon|Marano-Grado Lagoon]], with a surface area of around {{convert|160|km2|sqmi|0|abbr=off}}, is the northernmost lagoon in the Adriatic Sea and is sometimes called the "twin sister of the Venice lagoon". |

||

==Development== |

==Development== |

||

The Lagoon of Venice is the most important survivor of a system of [[Estuary|estuarine]] lagoons that in Roman times extended from [[Ravenna]] north to [[Trieste]]. In the sixth |

The Lagoon of Venice is the most important survivor of a system of [[Estuary|estuarine]] lagoons that in Roman times extended from [[Ravenna]] north to [[Trieste]]. In the fifth and sixth centuries, the Lagoon gave security to Romanised people fleeing invaders (mostly the [[Huns]] and the [[Lombards]]). Later, it provided naturally protected conditions for the growth of the [[Venetian Republic]] and its [[Thalassocracy|maritime empire]]. It still provides a base for a [[seaport]], the [[Venetian Arsenal]], and for [[fishing]], as well as a limited amount of [[hunting]] and the newer industry of [[fish farming]]. |

||

The Lagoon was formed about six to seven thousand years ago, when the marine transgression following the [[Ice Age]] flooded the upper Adriatic coastal plain.{{#tag:ref|This geological history follows {{harvp|Brambati|Carbognin|Quaia|Teatini|2003}}.<ref>{{cite journal |first1 = Antonio |last1 = Brambati |first2 = Laura |last2 = Carbognin |first3 = Tullio |last3 = Quaia |first4 = Pietro |last4 = Teatini |first5 = Luigi |last5 = Tosi |name-list-style = amp |year = 2003 |title = The Lagoon of Venice: Geological Setting, Evolution and Land Subsidence |journal = [[Episodes (journal)|Episodes]] |volume = 26 |issue = 3 |pages = 264–268 |doi = 10.18814/epiiugs/2003/v26i3/020 |url = http://www.episodes.co.in/www/backissues/263/19Brambati.pdf | |

The Lagoon was formed about six to seven thousand years ago, when the [[marine transgression]] following the [[Last Glacial Period|Ice Age]] flooded the upper Adriatic coastal plain.{{#tag:ref|This geological history follows {{harvp|Brambati|Carbognin|Quaia|Teatini|2003}}.<ref>{{cite journal |first1 = Antonio |last1 = Brambati |first2 = Laura |last2 = Carbognin |first3 = Tullio |last3 = Quaia |first4 = Pietro |last4 = Teatini |first5 = Luigi |last5 = Tosi |name-list-style = amp |year = 2003 |title = The Lagoon of Venice: Geological Setting, Evolution and Land Subsidence |journal = [[Episodes (journal)|Episodes]] |volume = 26 |issue = 3 |pages = 264–268 |doi = 10.18814/epiiugs/2003/v26i3/020 |url = http://www.episodes.co.in/www/backissues/263/19Brambati.pdf |doi-access = free }}</ref> |group=lower-alpha}} Deposition of river sediments compensated for the sinking coastal plain, and coastwise drift from the mouth of the [[Po River|Po]] tended to form sandbars that closed tidal inlets. |

||

[[File:2001-NASA-Satellitenaufnahme Venedig.jpg|thumb|Venetian lagoon from above]]{{clear}}The present aspect of the Lagoon is |

[[File:2001-NASA-Satellitenaufnahme Venedig.jpg|thumb|Venetian lagoon from above]]{{clear}}The present aspect of the Lagoon is the result of human intervention. In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, Venetian hydraulic projects designed to prevent the lagoon from turning into a marsh reversed the natural evolution of the Lagoon. Pumping of [[aquifer]]s since the nineteenth century has increased [[subsidence]]. Many of the Lagoon's islands had originally been marshy, but a gradual drainage programme rendered them habitable. Many of the smaller islands are entirely artificial, while some areas around the seaport of the [[Mestre]] are also reclaimed islands. The remaining islands—-including those of the coastal strip ([[Lido di Venezia|Lido]], [[Pellestrina]] and [[Treporti]])—-are essentially [[dune]]s. |

||

Venice Lagoon |

Venice Lagoon has been inhabited from the most ancient times, but it was only during and after the [[fall of the Western Roman Empire]] that people coming from the [[Veneto|Venetian mainland]] settled in numbers large enough to found the city of [[Venice]]. Today, the main cities inside the lagoon are Venice (at the centre of it) and [[Chioggia]] (at the southern inlet); [[Lido di Venezia]] and [[Pellestrina]] are inhabited as well, but they are considered part of Venice. However, most of the inhabitants of Venice, as well as its economic core (its airport and harbor), are on the western border of the lagoon, around the former towns of [[Mestre]] and [[Marghera]]. There are also two towns at the northern end of the lagoon: [[Jesolo]] (a famous sea resort) and [[Cavallino-Treporti]]. |

||

==Ecosystem== |

==Ecosystem== |

||

[[File:Food web of the Venice lagoon.png|thumb|upright=1| {{center|[[Food web]] diagram of the Venetian Lagoon<ref>Heymans, J.J., Coll, M., Libralato, S., Morissette, L. and Christensen, V. (2014). "Global patterns in ecological indicators of marine food webs: a modelling approach". ''PLOS ONE'', '''9'''(4). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0095845.</ref><ref>Pranovi, F., Libralato, S., Raicevich, S., Granzotto, A., Pastres, R. and Giovanardi, O. (2003). "Mechanical clam dredging in Venice lagoon: ecosystem effects evaluated with a trophic mass-balance model". ''Marine Biology'', '''143'''(2): 393–403. doi:10.1007/s00227-003-1072-1.</ref>}}]] |

[[File:Food web of the Venice lagoon.png|thumb|upright=1| {{center|[[Food web]] diagram of the Venetian Lagoon<ref>Heymans, J.J., Coll, M., Libralato, S., Morissette, L. and Christensen, V. (2014). "Global patterns in ecological indicators of marine food webs: a modelling approach". ''PLOS ONE'', '''9'''(4). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0095845.</ref><ref>Pranovi, F., Libralato, S., Raicevich, S., Granzotto, A., Pastres, R. and Giovanardi, O. (2003). "Mechanical clam dredging in Venice lagoon: ecosystem effects evaluated with a trophic mass-balance model". ''Marine Biology'', '''143'''(2): 393–403. doi:10.1007/s00227-003-1072-1.</ref>}}]] |

||

[[Bottlenose dolphin]]s occasionally enter the lagoon, possibly for feeding.<ref>{{Cite web| last1 = Ferretti | first1 = Sabrina | last2 = Bearzi | first2 = Giovanni | title = Rare Report of a Bottlenose Dolphin Foraging in the Venice Lagoon, Italy | url = http://www.adriawatch.provincia.rimini.it/documenti/CETACEI/Ferretti_Bearzi.pdf | publisher = [[Tethys Research Institute]] | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20150402155709/http://www.adriawatch.provincia.rimini.it/documenti/CETACEI/Ferretti_Bearzi.pdf | archive-date = 2 April 2015 | url-status = dead | access-date = 15 March 2015}}</ref> |

|||

The level of pollution in the lagoon has long been a concern<ref>{{Cite journal | last1 = Grancini | first1 = Gianfranco | last2 = Cescon | first2 = Bruno | name-list-style = amp | year = 1971 | title = Observations of Dispersal Processes of Pollutants in Venice Lagoon and in the Po River Coastal Area | journal = Liège Colloquium on Ocean Hydrodynamics | volume = 2 | pages = 99–110 | publisher = Société Royale des Sciences de Liège }}</ref><ref>{{Cite book | editor1-last = Lasserre | editor1-first = Pierre | editor2-last = Marzollo | editor2-first = Angelo | year = 2000 | title = The Venice Lagoon Ecosystem: Inputs and Interactions Between Land and Sea | series = Man and the Biosphere Series | volume = 25 | location = Paris | publisher = Parthenon | isbn = 978-92-3-103595-1 }}</ref> The large [[phytoplankton]] and [[macroalgae]] blooms |

The level of pollution in the lagoon has long been a concern<ref>{{Cite journal | last1 = Grancini | first1 = Gianfranco | last2 = Cescon | first2 = Bruno | name-list-style = amp | year = 1971 | title = Observations of Dispersal Processes of Pollutants in Venice Lagoon and in the Po River Coastal Area | journal = Liège Colloquium on Ocean Hydrodynamics | volume = 2 | pages = 99–110 | publisher = Société Royale des Sciences de Liège }}</ref><ref>{{Cite book | editor1-last = Lasserre | editor1-first = Pierre | editor2-last = Marzollo | editor2-first = Angelo | year = 2000 | title = The Venice Lagoon Ecosystem: Inputs and Interactions Between Land and Sea | series = Man and the Biosphere Series | volume = 25 | location = Paris | publisher = Parthenon | isbn = 978-92-3-103595-1 }}</ref> The large [[phytoplankton]] and [[macroalgae]] blooms in the late 1980s proved particularly devastating.<ref>{{Cite journal | last1 = Sfriso | first1 = A. | last2 = Pavoni | first2 = B. | last3 = Marcomini | first3 = A. | last4 = Orio | first4 = A. A. | name-list-style = amp | year = 1992 | title = Macroalgae, Nutrient Cycles, and Pollutants in the Lagoon of Venice | journal = Estuaries | volume = 15 | issue = 4 | pages = 517–528 | jstor = 1352394 | doi = 10.2307/1352394 | s2cid = 84000695 }}</ref><ref name="Pranovi">{{Cite journal | last1 = Pranovi | first1 = Fabio | last2 = Da Ponte | first2 = Filippo | last3 = Torricelli | first3 = Patrizia | name-list-style = amp | year = 2007 | title = Application of Biotic Indices and Relationship with Structural and Functional Features of Macrobenthic Community in the Lagoon of Venice: An Example over a Long Time Series of Data | journal = Marine Pollution Bulletin | volume = 54 | issue = 10 | pages = 1607–1618 | doi = 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2007.06.010 | pmid = 17698152 | bibcode = 2007MarPB..54.1607P | url = https://arca.unive.it/retrieve/handle/10278/3815/19079/Pranovi%20et%20al_07_MPB.pdf | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20151225024059/https://arca.unive.it/retrieve/handle/10278/3815/19079/Pranovi%20et%20al_07_MPB.pdf | archive-date = 25 December 2015 | url-status = live }}</ref> Researchers have identified the lagoon as one of the primary areas where non-indigenous species are introduced into the [[Mediterranean Sea]].<ref>{{Cite journal | last1 = Occhipinti-Ambrogi | first1 = Anna | last2 = Savini | first2 = Dario | name-list-style = amp | year = 2003 | title = Biological Invasions as a Component of Global Change in Stressed Marine Ecosystems | journal = Marine Pollution Bulletin | volume = 46 | issue = 5 | pages = 542–551 | doi = 10.1016/S0025-326X(02)00363-6 | pmid = 12735951 | bibcode = 2003MarPB..46..542O | url = https://www.researchgate.net/publication/10769699 }} |

||

</ref><ref> |

</ref><ref> |

||

{{Cite journal |

{{Cite journal |

||

| Line 84: | Line 85: | ||

| volume = 17 | issue = 10 | pages = 2943–2962 |

| volume = 17 | issue = 10 | pages = 2943–2962 |

||

| doi = 10.1007/s10530-015-0922-3 |

| doi = 10.1007/s10530-015-0922-3 |

||

| bibcode = 2015BiInv..17.2943M |

|||

| hdl = 10278/3661477 |

| hdl = 10278/3661477 |

||

| s2cid = 17434132 |

| s2cid = 17434132 |

||

| url = https://iris.unive.it/bitstream/10278/3661477/3/Biological%20Invasions.pdf |

| url = https://iris.unive.it/bitstream/10278/3661477/3/Biological%20Invasions.pdf |

||

| hdl-access = free |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

</ref> |

</ref> |

||

[[File:2020-10-20 Lazzaretto Nuovo05.jpg|thumb|alt=Orange-brown grasses bend in the wind on Lazzaretto Nuovo. |Grasses on Lazzaretto Nuovo]] |

|||

Cruise ships crossing the Venetian Lagoon have contributed to air pollution, surface-water pollution, decreased water quality, erosion, and loss of landscape.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://ejatlas.org/conflict/cruise-ships-in-venetian-lagoon|title=Cruise Ships impacting Venetian Lagoon, Italy {{!}} EJAtlas|last=EJOLT|website=[[Environmental Justice Atlas]]|language=en|access-date=2020-04-20}}</ref> |

|||

From 1987 to 2003, the Venice Lagoon was |

From 1987 to 2003, the Venice Lagoon was harmed by a reduction in nutrient inputs and by macroalgal biomasses caused by [[global climate change|climate change]], and by changes in the concentration and distribution of [[nitrogen]], organic [[phosphorus]] and [[organic carbon]] in the upper sediments. At the same time, however, the [[seagrass]]es started a natural process of recolonization, helping to partially restore the pristine conditions of the marine ecosystem.<ref>{{cite journal | title = Natural Recovery and Planned Intervention in Coastal Wetlands: Venice Lagoon (Northern Adriatic Sea, Italy) as a Case Study | doi = 10.1155/2014/968618 | journal = The Scientific World Journal | year = 2014 | volume = 2014 | issue = Article ID 968618 | author = Sonia Ceoldo |author2= Nicola Pellegrino | author3 =Adriano Sfriso | pages = 1–15 | pmid = 25126611 | pmc = 4122138 | oclc = 8255474034 |issn = 1537-744X | doi-access = free }}</ref> |

||

==Islands== |

==Islands== |

||

| Line 108: | Line 112: | ||

*[[Mazzorbo]] 0.52 km{{sup|2}} |

*[[Mazzorbo]] 0.52 km{{sup|2}} |

||

*[[Torcello]] 0.44 km{{sup|2}} |

*[[Torcello]] 0.44 km{{sup|2}} |

||

*[[Sant'Elena]] 0.34 km{{sup|2}} |

*[[Sant'Elena (island)|Sant'Elena]] 0.34 km{{sup|2}} |

||

*[[La Certosa]] 0.24 km{{sup|2}} |

*[[La Certosa]] 0.24 km{{sup|2}} |

||

*[[Burano]] 0.21 km{{sup|2}} |

*[[Burano]] 0.21 km{{sup|2}} |

||

| Line 132: | Line 136: | ||

*[[San Pietro di Castello (island)|San Pietro di Castello]] |

*[[San Pietro di Castello (island)|San Pietro di Castello]] |

||

*[[San Servolo]] |

*[[San Servolo]] |

||

*[[Santo Spirito ( |

*[[Santo Spirito (island)|Santo Spirito]] |

||

*[[Sottomarina]] |

*[[Sottomarina]] |

||

*[[Vignole]] |

*[[Vignole]] |

||

| Line 164: | Line 168: | ||

{{Portal bar|Geography|Islands|Italy}} |

{{Portal bar|Geography|Islands|Italy}} |

||

{{Authority control}} |

{{Authority control}} |

||

[[Category:Venetian Lagoon| ]] |

[[Category:Venetian Lagoon| ]] |

||

[[Category:Geography of Venice]] |

[[Category:Geography of Venice]] |

||

Revision as of 00:14, 15 September 2024

| Venetian Lagoon | |

|---|---|

Aerial view of the Venetian Lagoon, showing many of the islands including Venice itself, center rear, with the bridge to the mainland | |

| Location | Venice, Veneto, Italy |

| Coordinates | 45°24′47″N 12°17′50″E / 45.41306°N 12.29722°E |

| Primary outflows | Adriatic Sea |

| Basin countries | Italy |

| Surface area | 550 square kilometres (210 sq mi) |

| Average depth | 10.5 metres (34 ft) |

| Max. depth | 21.5 metres (71 ft) |

| Surface elevation | 3 m (9.8 ft) |

| Settlements | Venice, Campagna Lupia, Cavallino-Treporti, Chioggia, Codevigo, Jesolo, Mira, Musile di Piave, Quarto d'Altino, San Donà di Piave |

| Official name | Laguna di Venezia: Valle Averto |

| Designated | 11 April 1989 |

| Reference no. | 423[1] |

The Venetian Lagoon (Italian: Laguna di Venezia; Template:Lang-vec) is an enclosed bay of the Adriatic Sea, in northern Italy, in which the city of Venice is situated. Its name in the Italian and Venetian languages, Laguna Veneta (cognate of Latin lacus 'lake'), has provided the English name for an enclosed, shallow embayment of salt water: a lagoon.

Location

The Venetian Lagoon stretches from the River Sile in the north to the Brenta in the south, with a surface area of around 550 square kilometres (212 square miles). It is around 8% land, including Venice itself and many smaller islands. About 11% is permanently covered by open water, or canals, as the network of dredged channels are called, while around 80% consists of mud flats, tidal shallows and salt marshes. The Lagoon is the largest wetland in the Mediterranean Basin.[2]

It is connected to the Adriatic Sea by three inlets: Lido, Malamocco and Chioggia. Situated at one end of a largely enclosed sea, the lagoon is subject to large variations in its water level.[3] The most extreme are the spring tides known as the acqua alta (Italian for "high water"), which regularly flood much of Venice.

The nearby Marano-Grado Lagoon, with a surface area of around 160 square kilometres (62 square miles), is the northernmost lagoon in the Adriatic Sea and is sometimes called the "twin sister of the Venice lagoon".

Development

The Lagoon of Venice is the most important survivor of a system of estuarine lagoons that in Roman times extended from Ravenna north to Trieste. In the fifth and sixth centuries, the Lagoon gave security to Romanised people fleeing invaders (mostly the Huns and the Lombards). Later, it provided naturally protected conditions for the growth of the Venetian Republic and its maritime empire. It still provides a base for a seaport, the Venetian Arsenal, and for fishing, as well as a limited amount of hunting and the newer industry of fish farming.

The Lagoon was formed about six to seven thousand years ago, when the marine transgression following the Ice Age flooded the upper Adriatic coastal plain.[a] Deposition of river sediments compensated for the sinking coastal plain, and coastwise drift from the mouth of the Po tended to form sandbars that closed tidal inlets.

The present aspect of the Lagoon is the result of human intervention. In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, Venetian hydraulic projects designed to prevent the lagoon from turning into a marsh reversed the natural evolution of the Lagoon. Pumping of aquifers since the nineteenth century has increased subsidence. Many of the Lagoon's islands had originally been marshy, but a gradual drainage programme rendered them habitable. Many of the smaller islands are entirely artificial, while some areas around the seaport of the Mestre are also reclaimed islands. The remaining islands—-including those of the coastal strip (Lido, Pellestrina and Treporti)—-are essentially dunes.

Venice Lagoon has been inhabited from the most ancient times, but it was only during and after the fall of the Western Roman Empire that people coming from the Venetian mainland settled in numbers large enough to found the city of Venice. Today, the main cities inside the lagoon are Venice (at the centre of it) and Chioggia (at the southern inlet); Lido di Venezia and Pellestrina are inhabited as well, but they are considered part of Venice. However, most of the inhabitants of Venice, as well as its economic core (its airport and harbor), are on the western border of the lagoon, around the former towns of Mestre and Marghera. There are also two towns at the northern end of the lagoon: Jesolo (a famous sea resort) and Cavallino-Treporti.

Ecosystem

Bottlenose dolphins occasionally enter the lagoon, possibly for feeding.[7]

The level of pollution in the lagoon has long been a concern[8][9] The large phytoplankton and macroalgae blooms in the late 1980s proved particularly devastating.[10][11] Researchers have identified the lagoon as one of the primary areas where non-indigenous species are introduced into the Mediterranean Sea.[12][13]

Cruise ships crossing the Venetian Lagoon have contributed to air pollution, surface-water pollution, decreased water quality, erosion, and loss of landscape.[14]

From 1987 to 2003, the Venice Lagoon was harmed by a reduction in nutrient inputs and by macroalgal biomasses caused by climate change, and by changes in the concentration and distribution of nitrogen, organic phosphorus and organic carbon in the upper sediments. At the same time, however, the seagrasses started a natural process of recolonization, helping to partially restore the pristine conditions of the marine ecosystem.[15]

Islands

The Venice Lagoon is mostly included in the Metropolitan City of Venice, but the south-western area is part of the Province of Padua.

The largest islands or archipelagos by area, excluding coastal reclaimed land and the coastal barrier beaches:

- Venice 5.17 km2

- Sant'Erasmo 3.26 km2

- Murano 1.17 km2

- Chioggia 0.67 km2

- Giudecca 0.59 km2

- Mazzorbo 0.52 km2

- Torcello 0.44 km2

- Sant'Elena 0.34 km2

- La Certosa 0.24 km2

- Burano 0.21 km2

- Tronchetto 0.18 km2

- Sacca Fisola 0.18 km2

- San Michele 0.16 km2

- Sacca Sessola 0.16 km2

- Santa Cristina 0.13 km2

Other inhabited islands include:

- Cavallino

- Lazzaretto Nuovo

- Lazzaretto Vecchio

- Lido

- Pellestrina

- Poveglia

- San Clemente

- San Francesco del Deserto

- San Giorgio in Alga

- San Giorgio Maggiore

- San Lazzaro degli Armeni

- Santa Maria della Grazia

- San Pietro di Castello

- San Servolo

- Santo Spirito

- Sottomarina

- Vignole

See also

Notes

- ^ This geological history follows Brambati et al. (2003).[4]

References

- ^ "Laguna di Venezia: Valle Averto". Ramsar Sites Information Service. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- ^ Poggioli, Sylvia (7 January 2008). "MOSE Project Aims to Part Venice Floods". Morning Edition (Radio program). NPR.

- ^ "Venice, Italy (1985–2003) - 25 Years of Landsat 5 - Landsat 5 showcase - Earth Watching". earth.esa.int. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- ^ Brambati, Antonio; Carbognin, Laura; Quaia, Tullio; Teatini, Pietro & Tosi, Luigi (2003). "The Lagoon of Venice: Geological Setting, Evolution and Land Subsidence" (PDF). Episodes. 26 (3): 264–268. doi:10.18814/epiiugs/2003/v26i3/020.

- ^ Heymans, J.J., Coll, M., Libralato, S., Morissette, L. and Christensen, V. (2014). "Global patterns in ecological indicators of marine food webs: a modelling approach". PLOS ONE, 9(4). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0095845.

- ^ Pranovi, F., Libralato, S., Raicevich, S., Granzotto, A., Pastres, R. and Giovanardi, O. (2003). "Mechanical clam dredging in Venice lagoon: ecosystem effects evaluated with a trophic mass-balance model". Marine Biology, 143(2): 393–403. doi:10.1007/s00227-003-1072-1.

- ^ Ferretti, Sabrina; Bearzi, Giovanni. "Rare Report of a Bottlenose Dolphin Foraging in the Venice Lagoon, Italy" (PDF). Tethys Research Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- ^ Grancini, Gianfranco & Cescon, Bruno (1971). "Observations of Dispersal Processes of Pollutants in Venice Lagoon and in the Po River Coastal Area". Liège Colloquium on Ocean Hydrodynamics. 2. Société Royale des Sciences de Liège: 99–110.

- ^ Lasserre, Pierre; Marzollo, Angelo, eds. (2000). The Venice Lagoon Ecosystem: Inputs and Interactions Between Land and Sea. Man and the Biosphere Series. Vol. 25. Paris: Parthenon. ISBN 978-92-3-103595-1.

- ^ Sfriso, A.; Pavoni, B.; Marcomini, A. & Orio, A. A. (1992). "Macroalgae, Nutrient Cycles, and Pollutants in the Lagoon of Venice". Estuaries. 15 (4): 517–528. doi:10.2307/1352394. JSTOR 1352394. S2CID 84000695.

- ^ Pranovi, Fabio; Da Ponte, Filippo & Torricelli, Patrizia (2007). "Application of Biotic Indices and Relationship with Structural and Functional Features of Macrobenthic Community in the Lagoon of Venice: An Example over a Long Time Series of Data" (PDF). Marine Pollution Bulletin. 54 (10): 1607–1618. Bibcode:2007MarPB..54.1607P. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2007.06.010. PMID 17698152. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 December 2015.

- ^ Occhipinti-Ambrogi, Anna & Savini, Dario (2003). "Biological Invasions as a Component of Global Change in Stressed Marine Ecosystems". Marine Pollution Bulletin. 46 (5): 542–551. Bibcode:2003MarPB..46..542O. doi:10.1016/S0025-326X(02)00363-6. PMID 12735951.

- ^ Marchini, Agnese; Ferrario, Jasmine; Sfriso, Adriano & Occhipinti-Ambrogi, Anna (2015). "Current Status and Trends of Biological Invasions in the Lagoon of Venice, a Hotspot of Marine NIS Introductions in the Mediterranean Sea" (PDF). Biological Invasions. 17 (10): 2943–2962. Bibcode:2015BiInv..17.2943M. doi:10.1007/s10530-015-0922-3. hdl:10278/3661477. S2CID 17434132.

- ^ EJOLT. "Cruise Ships impacting Venetian Lagoon, Italy | EJAtlas". Environmental Justice Atlas. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- ^ Sonia Ceoldo; Nicola Pellegrino; Adriano Sfriso (2014). "Natural Recovery and Planned Intervention in Coastal Wetlands: Venice Lagoon (Northern Adriatic Sea, Italy) as a Case Study". The Scientific World Journal. 2014 (Article ID 968618): 1–15. doi:10.1155/2014/968618. ISSN 1537-744X. OCLC 8255474034. PMC 4122138. PMID 25126611.

Further reading

- Brown, Horatio (1884). Life on the Lagoons. Additional editions printed in 1900, 1904, & 1909; paperback in 2008.

External links

- Atlas of the Lagoon - 103 thematic maps and associated explanations grouped in five sections: Geosphere, Biosphere, Anthroposphere, Protected Environments and Integrated Analysis

- SIL – Sistema Informativo della Laguna di Venezia

- Lagoon of Venice information

- Satellite image from Google Maps

- MILVa – Interactive Map of Venice Lagoon

- Comune di Venezia, Servizio Mobilità Acquea, Thematic cartography of Venice Lagoon

- Photo gallery by Enrico Martino about Venice's lagoon small islands, night life