Bharti Lalwani

Bharti Lalwani is a critic who takes a special interest in Southeast Asian art. She focuses on the region's histories, politics, religious traditions, and hybrid identities that value a pluralist and universal outlook. With respect to the local, Bharti sharpens her global perspective by connecting art practices that operate outside of nationalist narratives and divisions.

Bharti contributes to various art journals and publications. She has a Masters in Contemporary Art from Sotheby's Institute (Singapore) and a Bachelors in Fine Art from Central Saint Martins (London). In 2015, AICA Austria selected her as the founding Critic-in-Residence at Kunsthaus Wien (Vienna). In 2014, she was nominated Forbes Art Writer of the Year (India). The same year, she was the only contender to be nominated from three Southeast Asian countries (Thailand, Singapore and the Philippines) for the 'Prudential Eye Award: Best Writing on Asian Contemporary Art' and was short-listed among top the five. She is also a perfumer working with artists to create fragrances that could be incorporated into their art installations.

Hailing from Nigeria, she has lived in Lagos, London, Singapore and India. She considers herself a cosmopolitan who belongs everywhere and nowhere.

Various reports on art fairs, biennales and Private Museums by Bharti can be accessed on Asia-Europe Foundation's portal www.culture360.asef.org

Bharti contributes to various art journals and publications. She has a Masters in Contemporary Art from Sotheby's Institute (Singapore) and a Bachelors in Fine Art from Central Saint Martins (London). In 2015, AICA Austria selected her as the founding Critic-in-Residence at Kunsthaus Wien (Vienna). In 2014, she was nominated Forbes Art Writer of the Year (India). The same year, she was the only contender to be nominated from three Southeast Asian countries (Thailand, Singapore and the Philippines) for the 'Prudential Eye Award: Best Writing on Asian Contemporary Art' and was short-listed among top the five. She is also a perfumer working with artists to create fragrances that could be incorporated into their art installations.

Hailing from Nigeria, she has lived in Lagos, London, Singapore and India. She considers herself a cosmopolitan who belongs everywhere and nowhere.

Various reports on art fairs, biennales and Private Museums by Bharti can be accessed on Asia-Europe Foundation's portal www.culture360.asef.org

less

Related Authors

Claire Bishop

Graduate Center of the City University of New York

Remo Caponi

University of Cologne

Armando Marques-Guedes

UNL - New University of Lisbon

Michael W Charney

SOAS University of London

Martin O'Neill

University of York

Renata Holod

University of Pennsylvania

Alexander Nagel

New York University

Olga Palagia

National & Kapodistrian University of Athens

Manuel Parada López de Corselas

Universidad Complutense de Madrid

Thongchai Winichakul ธงชัย วินิจจะกูล

University of Wisconsin-Madison

InterestsView All (9)

Uploads

Papers by Bharti Lalwani

https://www.asiavillenews.com/search/bharti%20lalwani

When I moved to India early 2013, one of the first Indian artists I met were Ranbir and his wife Rashmi Kaleka. Their practice consistently communicated something intangible – While Rashmi has recorded and archived the sing-song call of street vendors and hawkers over a decade not unlike an anthropologist, Ranbir’s multi dimensional artworks transport the viewer to a different time and place through sensorial cues such as sound, stills and other cinematic elements. But some of his key works such as ‘MAN WITH BHUTTA’ (1999) – was inspired by the smell of corn toasted on an open charcoal flame on the streets during the monsoons. When I started creating perfumes, Ranbir and I had extensive conversations on how to express a series of memories through scent – A fleeting olfactive sensation so powerful as to pull the individual through time and space to a specific moment in history and memory.

https://litrahbperfumery.com/memories-of-kaleka/

religion—were tackled head-on at two events in New York: the exhibition

“Lucid Dreams and Distant Visions: South Asian Art in the Diaspora” at Asia

Society Museum, and the two-day conference “Fatal Love: Where Are We

Now?” at the Asia Society Museum and Queens Museum.

Nineteen South-Asian-American artists explored the narratives of

recent immigrants, second-generation Americans and transnational artists

working in and around South Asia and America in “Lucid Dreams and

Distant Visions.” The exhibition was a microcosm of what defines the

American experience. Here, numerous artworks examined the notion

of home through intertwined personal and political histories within the

framework of systemically biased and oppressive structures of authority.

Artist-activist Jaishri Abichandani, who conceived of “Lucid Dreams

and Distant Visions,” co-curated this exhibition with Tan Boon Hui (vice

president for Global Arts and Cultural Programs and director of Asia

Society Museum) and Lawrence-Minh Davis (curator at Smithsonian

Asian Pacific American Center [APAC]). <<

>>Exhibition-catalogues are significant. However big the show, once taken down, it is primarily the catalogue, that speaks for the exhibition-artworks’ relationship with each other and the larger field. When the field is young and undecided, the catalogue, embodying the curator’s vision and position, matters more. This critic’s own knowledge of Southeast Asian art is grounded in the scholarship built through multiple-essay catalogues of historically relevant shows. A number of these were produced by Japan’s institutions, particularly with the opening of the Fukuoka Art Museum in 1979. Take for instance the principal text from the catalogue of one such regional exhibition, ‘Art in Southeast Asia 1997: Glimpses into the Future’, produced by The Japan Foundation Asia Centre in ‘97. Curator Junichi Shioda’s essay ‘Glimpses into the Future of Southeast Asian Art: A Vision of what Art should be’, constructed and cross-examined the idea of a regional canon, independent from Euramerican modernism, through the socially-rooted practices of artists from five Southeast Asian countries. Two other academic essays in this exhibition-catalogue further provided analyses of art in Southeast Asia and contemporary art in Indonesia.

Around the same time, a similarly vital exhibition ‘Contemporary Art in Asia: Traditions/Tensions’ was curated by Thai scholar Apinan Poshyananda. This exhibition’s catalogue included seven essays that built the discourse around the politically charged practices of various Southeast Asian artists among others from Asia. Such exhibition-catalogues sought intellectual contributions from field-scholars who connect socio-economic complexities, and ground artistic practices in their respective historical, cultural and political contexts. Such catalogue-essays, written two decades ago or today, are important to establishing the canon around Southeast Asian art because scholarly analyses of exhibition artworks, and their comparison with other pieces, permit the discerning of larger currents and parallels that give shape to the field. That artists from Southeast Asia have been potent voices for social change and reformation is established through scholars’ analyses of artworks presented in writing for exhibition-catalogues, past and present.<<

With an audience that was welcoming and curious, I had an invaluable opportunity to share my learnings on the history and art of Southeast Asia (SEA) - not as a presumed expert on the region but as a student, a specialist critic, still grasping at the diversity of SEA countries. Previous editions of TAKE on art magazine have given me great editorial freedom to review exhibitions and biennales from this part of the world which, in my view, is often overlooked in the international sphere save for the discussions on global art markets. Speaking in Baroda not only permitted the possibility to share what I have learnt but to also have my views tested, challenged and discussed within a safe but intellectually rigorous space in the presence of stalwarts from the Indian art scene.

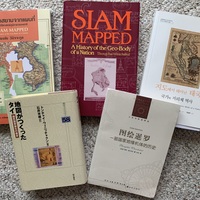

Understanding art from any particular region requires for its entangled historical, socio-political, religious and cultural narratives to be contextualized in a manner that allows regional and international audiences to access its coded references and significance. Since my move to Singapore in 2008, I naturally encountered art that emerged from specific local circumstances. As an Indian hailing from Nigeria, I was evidently not a native of the region and I certainly did not come close to speaking any of the languages. Therefore, writing about regional art competently required considerable reading on my part that would enable me to transcend an artwork's obvious formal imperatives. I familiarized myself with regional history and the cultural, economic and political shifts of various countries, their anti-imperialist struggles and burgeoning nationalist ideologies that indeed many Southeast Asian artists critique.

In order to access what these artists were saying and how they were saying it, I oriented myself with Southeast Asian art through numerous exhibitions at institutions, galleries and young biennales across the region alongside conversations with artists and curators who kindled a sincere appreciation of the region's hybrid cosmopolitanism and historically inclusive, syncretic outlook, contemporary artists' agency and their voice for the dispossessed. Having written about various artworks beyond their specific 'local context' over some six years, I stand convinced that themes tackled by SEA artists would find common ground with Indian viewers unfamiliar with the region. And so I set about convincing the astute Baroda audience of Southeast Asian contemporary art's universal appeal. But first, contextualisation was key. I began by giving the audience a gist of crucial events from mid 20th century that shaped the political orientation of Burma, Vietnam, Cambodia, Philippines, Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia and Thailand. [...]

AICA-Kunsthaus Wien Critic Residency is an audacious initiative proposed by AICA President Sabine Vogel to nurture not a curator or an artist but an Art Critic who served no commercial interests.

regionally comprehensive curated exhibition (at the time of writing) to show at an institution outside of

Asia. Roving Eye is also the third in a trilogy of SE Asian contemporary art exhibitions curated chiefly by

Lenzi and based on her nearly two decades worth of research and scholarship: 'Negotiating Home, History,

Nation: Two Decades of Contemporary Art in Southeast Asia, 1991-2011' and 'Concept, Context,

Contestation: Art and the Collective in Southeast Asia'.

Both exhibitions were curated in collaboration with Southeast Asian curators and deliberately sited within

regional institutions so establishing SEA scholarship and art historical canon in Singapore in 2011 and

Bangkok in 2013, respectively. The art was naturally legible to audiences in Southeast Asia. Where

Negotiating Home, History, Nation (NHHN) was an ambitious exhibition charting the region's art practices

over two decades, Concept, Context, Contestation (CCC) further teased out SEA artists' conceptualist bent

examined within the ambit of Southeast Asian history. This was not to deny or refute external artistic

influences (predominantly from the West) but to explore locally-rooted discourses that shaped practices

and defined traits central to the region's art. Generalizing about Southeast Asia could be dangerous

ofcourse and as such the region cannot be viewed as a monolith wherein diverse contexts are uncritically

lumped. This, Lenzi has been cautious of. In her various essays over nearly 20 years, she has cogently

factored in Southeast Asian countries' shared political awakening in the latter half of the 20th century and

its implications on regional art history.

And herein lay the potential risk of taking Southeast Asian art out into the world for a European and

predominantly Turkish audience through The Roving Eye. As argued by the premise of previous exhibitions,

if much of Southeast Asian contemporary art erupted from its volatile socio-political circumstances, would

such art be legible to an audience unfamiliar with Southeast Asia?

ushered in sweeping transformations along with opportunities to strengthen international cultural ties and

foster inter-regional artistic exchanges. As Myanmar heralds an ostensibly new era for freedom of

expression, artistically testing its limits is the recent exhibition 'Building Histories' at Goethe Villa in Yangon.

https://www.asiavillenews.com/search/bharti%20lalwani

When I moved to India early 2013, one of the first Indian artists I met were Ranbir and his wife Rashmi Kaleka. Their practice consistently communicated something intangible – While Rashmi has recorded and archived the sing-song call of street vendors and hawkers over a decade not unlike an anthropologist, Ranbir’s multi dimensional artworks transport the viewer to a different time and place through sensorial cues such as sound, stills and other cinematic elements. But some of his key works such as ‘MAN WITH BHUTTA’ (1999) – was inspired by the smell of corn toasted on an open charcoal flame on the streets during the monsoons. When I started creating perfumes, Ranbir and I had extensive conversations on how to express a series of memories through scent – A fleeting olfactive sensation so powerful as to pull the individual through time and space to a specific moment in history and memory.

https://litrahbperfumery.com/memories-of-kaleka/

religion—were tackled head-on at two events in New York: the exhibition

“Lucid Dreams and Distant Visions: South Asian Art in the Diaspora” at Asia

Society Museum, and the two-day conference “Fatal Love: Where Are We

Now?” at the Asia Society Museum and Queens Museum.

Nineteen South-Asian-American artists explored the narratives of

recent immigrants, second-generation Americans and transnational artists

working in and around South Asia and America in “Lucid Dreams and

Distant Visions.” The exhibition was a microcosm of what defines the

American experience. Here, numerous artworks examined the notion

of home through intertwined personal and political histories within the

framework of systemically biased and oppressive structures of authority.

Artist-activist Jaishri Abichandani, who conceived of “Lucid Dreams

and Distant Visions,” co-curated this exhibition with Tan Boon Hui (vice

president for Global Arts and Cultural Programs and director of Asia

Society Museum) and Lawrence-Minh Davis (curator at Smithsonian

Asian Pacific American Center [APAC]). <<

>>Exhibition-catalogues are significant. However big the show, once taken down, it is primarily the catalogue, that speaks for the exhibition-artworks’ relationship with each other and the larger field. When the field is young and undecided, the catalogue, embodying the curator’s vision and position, matters more. This critic’s own knowledge of Southeast Asian art is grounded in the scholarship built through multiple-essay catalogues of historically relevant shows. A number of these were produced by Japan’s institutions, particularly with the opening of the Fukuoka Art Museum in 1979. Take for instance the principal text from the catalogue of one such regional exhibition, ‘Art in Southeast Asia 1997: Glimpses into the Future’, produced by The Japan Foundation Asia Centre in ‘97. Curator Junichi Shioda’s essay ‘Glimpses into the Future of Southeast Asian Art: A Vision of what Art should be’, constructed and cross-examined the idea of a regional canon, independent from Euramerican modernism, through the socially-rooted practices of artists from five Southeast Asian countries. Two other academic essays in this exhibition-catalogue further provided analyses of art in Southeast Asia and contemporary art in Indonesia.

Around the same time, a similarly vital exhibition ‘Contemporary Art in Asia: Traditions/Tensions’ was curated by Thai scholar Apinan Poshyananda. This exhibition’s catalogue included seven essays that built the discourse around the politically charged practices of various Southeast Asian artists among others from Asia. Such exhibition-catalogues sought intellectual contributions from field-scholars who connect socio-economic complexities, and ground artistic practices in their respective historical, cultural and political contexts. Such catalogue-essays, written two decades ago or today, are important to establishing the canon around Southeast Asian art because scholarly analyses of exhibition artworks, and their comparison with other pieces, permit the discerning of larger currents and parallels that give shape to the field. That artists from Southeast Asia have been potent voices for social change and reformation is established through scholars’ analyses of artworks presented in writing for exhibition-catalogues, past and present.<<

With an audience that was welcoming and curious, I had an invaluable opportunity to share my learnings on the history and art of Southeast Asia (SEA) - not as a presumed expert on the region but as a student, a specialist critic, still grasping at the diversity of SEA countries. Previous editions of TAKE on art magazine have given me great editorial freedom to review exhibitions and biennales from this part of the world which, in my view, is often overlooked in the international sphere save for the discussions on global art markets. Speaking in Baroda not only permitted the possibility to share what I have learnt but to also have my views tested, challenged and discussed within a safe but intellectually rigorous space in the presence of stalwarts from the Indian art scene.

Understanding art from any particular region requires for its entangled historical, socio-political, religious and cultural narratives to be contextualized in a manner that allows regional and international audiences to access its coded references and significance. Since my move to Singapore in 2008, I naturally encountered art that emerged from specific local circumstances. As an Indian hailing from Nigeria, I was evidently not a native of the region and I certainly did not come close to speaking any of the languages. Therefore, writing about regional art competently required considerable reading on my part that would enable me to transcend an artwork's obvious formal imperatives. I familiarized myself with regional history and the cultural, economic and political shifts of various countries, their anti-imperialist struggles and burgeoning nationalist ideologies that indeed many Southeast Asian artists critique.

In order to access what these artists were saying and how they were saying it, I oriented myself with Southeast Asian art through numerous exhibitions at institutions, galleries and young biennales across the region alongside conversations with artists and curators who kindled a sincere appreciation of the region's hybrid cosmopolitanism and historically inclusive, syncretic outlook, contemporary artists' agency and their voice for the dispossessed. Having written about various artworks beyond their specific 'local context' over some six years, I stand convinced that themes tackled by SEA artists would find common ground with Indian viewers unfamiliar with the region. And so I set about convincing the astute Baroda audience of Southeast Asian contemporary art's universal appeal. But first, contextualisation was key. I began by giving the audience a gist of crucial events from mid 20th century that shaped the political orientation of Burma, Vietnam, Cambodia, Philippines, Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia and Thailand. [...]

AICA-Kunsthaus Wien Critic Residency is an audacious initiative proposed by AICA President Sabine Vogel to nurture not a curator or an artist but an Art Critic who served no commercial interests.

regionally comprehensive curated exhibition (at the time of writing) to show at an institution outside of

Asia. Roving Eye is also the third in a trilogy of SE Asian contemporary art exhibitions curated chiefly by

Lenzi and based on her nearly two decades worth of research and scholarship: 'Negotiating Home, History,

Nation: Two Decades of Contemporary Art in Southeast Asia, 1991-2011' and 'Concept, Context,

Contestation: Art and the Collective in Southeast Asia'.

Both exhibitions were curated in collaboration with Southeast Asian curators and deliberately sited within

regional institutions so establishing SEA scholarship and art historical canon in Singapore in 2011 and

Bangkok in 2013, respectively. The art was naturally legible to audiences in Southeast Asia. Where

Negotiating Home, History, Nation (NHHN) was an ambitious exhibition charting the region's art practices

over two decades, Concept, Context, Contestation (CCC) further teased out SEA artists' conceptualist bent

examined within the ambit of Southeast Asian history. This was not to deny or refute external artistic

influences (predominantly from the West) but to explore locally-rooted discourses that shaped practices

and defined traits central to the region's art. Generalizing about Southeast Asia could be dangerous

ofcourse and as such the region cannot be viewed as a monolith wherein diverse contexts are uncritically

lumped. This, Lenzi has been cautious of. In her various essays over nearly 20 years, she has cogently

factored in Southeast Asian countries' shared political awakening in the latter half of the 20th century and

its implications on regional art history.

And herein lay the potential risk of taking Southeast Asian art out into the world for a European and

predominantly Turkish audience through The Roving Eye. As argued by the premise of previous exhibitions,

if much of Southeast Asian contemporary art erupted from its volatile socio-political circumstances, would

such art be legible to an audience unfamiliar with Southeast Asia?

ushered in sweeping transformations along with opportunities to strengthen international cultural ties and

foster inter-regional artistic exchanges. As Myanmar heralds an ostensibly new era for freedom of

expression, artistically testing its limits is the recent exhibition 'Building Histories' at Goethe Villa in Yangon.

[...]The last forty years have been a fraught period of oppression where vestiges of colonialism still remain bolted firmly in place. Naturally, artists as citizens of newly independent nations, conscious of their emancipation and right to self-determination were part of the collective critique on authoritarian structures. Therefore, what conceptual tactics did artists deploy to communicate an array of abstract ideas, realities and dissent to cope within a world that was perpetually dismantling, collapsing and building itself back up again? What was the genesis of such conceptual thinking and how such 'local' art might be distinctly 'Southeast Asian' in character, but 'global' in its reading? These were some of the questions this exhibition attempted to answer, particularly in its lead curatorial essay.[...]