The American media and public have spent a fair bit of the past months being fascinated and appalled by various remarks from the Rev. Jeremiah Wright, of Chicago. Those months have also seen a fairly warm critical reception for Erykah Badu’s terrific new album—one whose notions and ideologies sometimes come from the same nexus as Wright’s. Badu’s theology is different, of course: more personal, more scattered, less Christian, laced with Five-Percenter notions. And Badu salutes Farrakhan explicitly, rather than just nodding politely across the South Side. But there’s an odd echo in her wording on that one: “I salute you, Farrakhan/Because you are me.” Less than a month after this record’s release, Wright’s most notable acquaintance was describing the reverend as someone who “contains within him the contradictions—the good and the bad—of the community…. I can no more disown him than I can disown the Black community.” He is me? Until he hits the press club, anyway.

New Amerykah is the first in a series of pointedly social records from Badu, and “you are me”—or maybe we are we—could be its motto, or possibly its intended effect. I don’t bring up politics for nothing. That attitude, and a lot of the record's concerns, have their roots in the same era that animates Rev. Wright—those Civil Rights and post–Civil Rights moments when African-Americans were left with some strange, heavy tasks: sorting out how to have a cultural identity as part of a nation that had, up until very recently, been a dedicated adversary, and sorting out how to clean up the wreckage that had accumulated in the meantime. A lot of the critical love for New Amerykah seems rooted in a love for the music of that period—a time in which popular Black artists made records filled not only with visionary, avant-garde sounds, but with a social expansiveness, a fire and ambition to say something important to and for a community. Reviews put this record in a line with those artists: Sly Stone, Marvin Gaye, Miles Davis, Stevie Wonder, Funkadelic; you could tie it even more easily to a lot of smart-guy late-’80s hip-hop digging into the same ideas. Nobody who’s been paying attention will be surprised at the thought of that mantle being picked up by a woman.

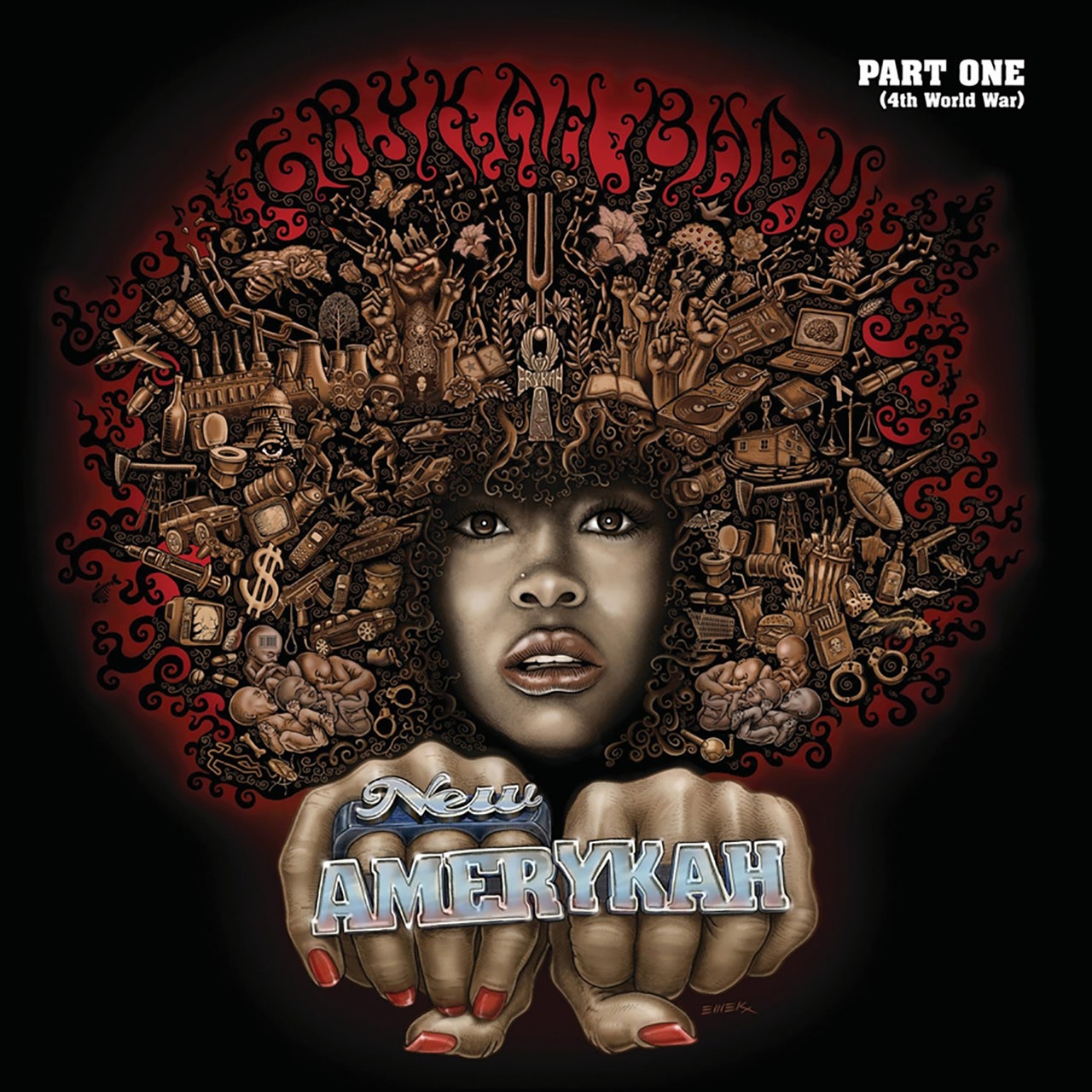

This album doesn’t just have the personal and social ambitions of those old records—plenty of charmless “nu-soul” records aspire to that—but some of the sonic ones, too. Big tracks aside, it’s an awfully static record, which gives it the kind of high-art “difficulty” that we critics have been known to like. The beats, by hip-hop producers like Madlib, 9th Wonder, and Shafiq Husayn, trail sneakily by, leaving Badu—without the aid of verses, choruses, or much structure at all—to scribble all over them in her perfect/imperfect voice. (One track, “My People,” is mostly just a repeated mantra; the rest of Badu’s vocal scribbling is buried far back in the mix, like an incidental decoration.) These things should pose problems; one of the chief wonders of New Amerykah is that they don’t. Instead, they allow for a sense of intimacy and freedom. At the end of one already-great track, there’s an offhand doodle that’s one of the most amazing pieces of music I’ve heard all year: It’s just Badu, with some chatter in the background, singing her mother’s history in unison with a muted trumpet. But you can hear the two musicians working happily to stay in unison, all through a complex jazz run, even trying to match their vibratos; you can imagine the takes where they miss it and laugh a little. It makes a little joke, and it closes on a terrific line about her mother’s resilience—“Even though it was hard, you would never ever know it”—and in the end I can't think of a nobler use for recording equipment.