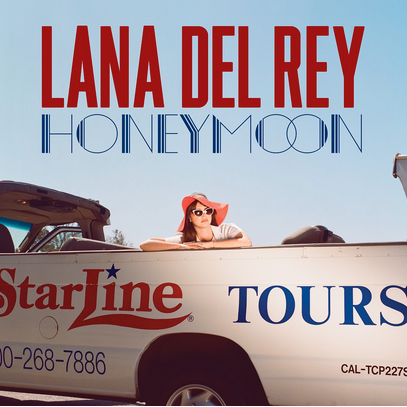

On the cover of Honeymoon, we see our star, Lana Del Rey, the idle passenger of a parked convertible Hollywood tourmobile, gazing behind her through face-obscuring shades. As an artist, she's never shied away from the obvious, but the image feels almost too on-the-nose, too apt—Lana doing The Full Lana. And yet, that's exactly what Honeymoon gives us—it is Lana Del Rey's purest album-length expression, and her most artistic one.

Accordingly, Honeymoon is a dark work, darker even than Ultraviolence, and the pall does not lift for its 60-plus minutes. It's an album about love, but "love", as Del Rey sings it, sounds like mourning. The romance here is closer to addiction—something that's sought for its ability to blot out the rest of life's miseries. On the title track, when she croons "Our honeymoon/ Say you want me too", she's dopily hopeful as Brian Wilson singing "We could be married/ And then we'll be happy." The album luxuriates in this bleak space between dream and reality, which stretches endlessly from one melancholy track to the next. It's not until "The Blackest Day", eleven songs in, that Honeymoon's static depression gives way to apocalyptic ecstasy, as she gasps "In all the wrong places/ Oh my God" in multi-tracked harmonies on the chorus. The moment is Honeymoon's emotional apex, but it still moves at the pace of a funeral march, and the release it depicts is that of embracing rock bottom.

The morose orchestral grandeur of the album feels like an arrival point, and also possibly a dead-end: the sentimentality and drama throws back to old Hollywood film scores. The setting is pitch-perfect and a million mothballed years away from the current pop landscape; it's strange, a barometer of youth culture trading in such old music. As a singer, Del Rey sounds more like the singer of her pre-Lana Lizzy Grant days here, when she was was performing torch songs in secretarial skirts at A&R showcases, looking too young to seem so haunted. Her previous two records felt like earnest stabs at finding a pop context for that voice, but they were both overwrought, and Honeymoon's arrangements feel built to rectify that.

Honeymoon acknowledges what, or rather who, we are here for. It knows that we want big, sad, fucked-up epics. It's rare to get to a chorus within the first minute, and until that point it's usually just Lana, maybe a little guitar or some cinematic strings. The programmed drums of "High by the Beach" and "Religion" wait nearly a minute to enter, and "Terrence Loves You" is even sparser. Many tracks expand sleepily past the five- or six-minute mark, which is to say that Honeymoon's languor takes our attention for granted. Which is certainly not a mistake.