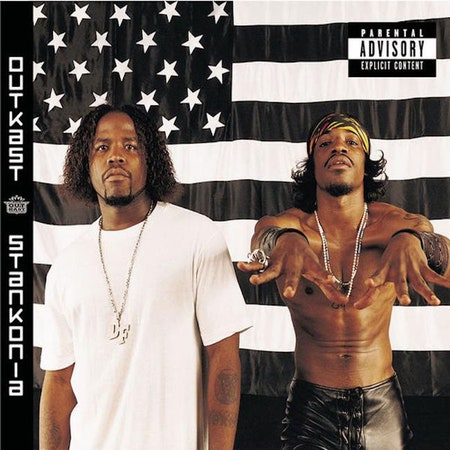

They always had chips on their shoulders, a grievance born of their distinctive authorship mixed with the civic pride of scrappy underdogs. They were André “3000” Benjamin and Antwan “Big Boi” Patton, but they went by an increasing array of colorful names—like Possum Aloysius Jenkins and Daddy Fat Sax—which seemed to exist only to expand minds and expectations while capturing the ideas that emanated from their craniums. They had emerged from southwest Atlanta with styles that were unforeseen, but quickly copied—the Kangol hats they wore in the video for “Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik” were soon seen atop the domes of Sean “Diddy” Combs and the Notorious B.I.G. after having been out of vogue for years. On the intro to Stankonia—their fourth album, a thrill-pushing auricular splattering of mindfunks and ideascapes—they mimicked those copying them by playfully reinterpreting the Atlanta “bounce” that had been spreading as the distraction of babies. Big Boi exhaled smoke and lamented, “Niggas ain’t even from the A-Town.”

Identity and location—and defining and observing the two on their own terms—have always been key with OutKast. All of their albums began with a disembodied intro track as a prelude, followed by a State of the OutKast declaration that proved that, as André would famously go on to say at the 1995 Source Awards, “the South got something to say.” Tellingly, André confessed, “I gots a lot of shit up on my mind,” on “Myintrotoletuknow” from their 1994 debut Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik. Their voices spat out harsh rhymes and stretched out melodic moments, but they also spoke about things widely and deeply, respecting and commenting on everything going on hip-hop, largely by ignoring everything going on in hip-hop. Their sonic brashness and directness had Public Enemy’s Chuck D in its DNA, their fashion had antecedents in the Grandmaster Flash & the Furious Five meeting Afrika Bambaataa’s Soul Sonic Force, the subversive whimsy of De La Soul and A Tribe Called Quest were their forebears, giving the group a musical intensity and breadth incomparable to any other major hip-hop act before or since. Those are weighty statements, but OutKast was OutKast—singular, inimitable, and unpredictable.

Their debut was an album bursting with the funk descended from the Isley Brothers, Isaac Hayes, and Curtis Mayfield in a way that was smoother than Dr. Dre’s G-funk stylings, more organic than Puff Daddy’s wholesale sampling of ’80s R&B, and more fluid and adventurous than hometown icon Jermaine Dupri’s sleek soul and pop arrangements. It was the music of Southern hip-hop, the “country rap tunes” pioneered by the late Pimp C, outfitted to a weary worldview that was cautious and specific about local dealings and paranoid about the greater world, but ultimately hopeful on universal levels—or, at least as hopeful as “Crumblin’ Erb” while “niggas killin’ niggas” can be.