Constructing Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason

Kenneth R. WESTPHAL

Department of Philosophy

Boðaziçi Üniversitesi, Ýstanbul

Wo Zusammengesetztheit ist, da ist Argument und Funktion, und wo diese

sind, sind bereits alle logischen Konstanten. – Wittgenstein, Tractatus §5.471

1

INTRODUCTION.

(4.09.2019)

Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason is as radically innovative and incisive as it is baffling in outline and

often in detail. It grew in stages, as Kant developed three successive, ever more adequate accounts of our human capacity to think, each successively responding to key problems or gaps

Kant found in its predecessor, starting from his own pre-Critical views. The two very different

published editions (1781, 1787) both belong to the third, final stage of Kant’s theory (Melnick

1989). Understandably, Kant re-worked his various working manuscripts, and then his first published edition. Unfortunately for us, his readers, he had not the occasion to revise the whole into

one entirely consistent and orderly text – in part because he grew to realize he had inaugurated

an entirely new, comprehensive approach to philosophy. This he called the ‘Critical Philosophy’,

presented in the three Critiques: the Critique of Pure Reason, the Critique of Practical Reason and the

Critique of Judgment, together with his Critical a priori first principles for theoretical and for practical philosophy, presented in the Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals, the Metaphysics of Morals,

the Metaphysical First Principles of Natural Science, and perhaps also in the Religion within the Limits of

Reason Alone.

Kant insisted – rightly, I believe – that reason is architectonic, and hence systematic, and he did

indeed develop his Critical philosophy systematically, thoroughly and integrally. This holds not

only of his Critical system of philosophy, but also each main work, including the Critique of Pure

Reason. Much discussion of Kant’s philosophy, especially Anglophone discussion, has focussed

on Kant’s unique transcendental idealism. Much more important is that, and how, Kant’s Critical

system of philosophy develops a systematic and comprehensive critique of rational judgment

and justification across the domain of our rational inquiries, also demarcating purported domains

in which we can only pretend to know (Westphal 2018a, §§2–3).

Here I reconstruct how Kant constructed his Critique of Pure Reason. I begin with Kant’s initial

clues (§2). There are two. One is Johann Nicolas Tetens’ innovation, to require demonstrating

the genuine cognitive use of a concept or principle by ‘realising’ it in this sense: demonstratively

indicating at least one relevant instance of that concept or principle (§2.1). The second is Kant’s

methodological challenge, to figure out how to identify credibly and accurately by philosophical

reflection the structure and functioning of sub-personal cognitive processes (§2.2). These are functions and conditions which must be satisfied, if we are to be at all self-conscious in the most ba1

‘Wherever there is compositeness, argument and function are present, and where these are present, we already

have all the logical constants’. This Tractarian statement is here given a very non-Tractarian use.

© 2019 Kenneth R. WESTPHAL; ALL rights reserved.

1

Work in progress; comments & critique welcome!

�sic ways we are. Kant departs radically from both rationalism and empiricism in this regard. I

then consider briefly why Kant holds that we have any a priori concepts (§3), taking up one of his

examples: the general concept of ‘cause’. Then Kant’s issues about perceptual synthesis are specified by four problems of sensory ‘binding’, as it is now known (§4). These issues are fundamental to sensory-perceptual discrimination and identification. One of Kant’s central tasks is to figure out what is required for such identification and discrimination to be at all possible for us.

What functions of sensory-perceptual syntheses must there be? Which such functions can or do

we exercise? Kant’s clue, of course, is Aristotle’s logic, which is now known to be both complete

and ever so empirically useful (§5). I elucidate these points by recounting the Square of Categorical Oppositions (§5.1) and briefly indicate how Aristotle’s syllogistic logic is cognitively fundamental, because it is the kind of logic of judgment and inference required to identify, develop,

assess and use classifications and taxonomies (§5.2). Aristotle’s logic provides Kant’s clue to the

twelve fundamental formal aspects of judging, identified and reconstructed by Michael Wolff

(§6). I then consider, briefly, how Kant uses his Table of twelve formal aspects judging to identify twelve fundamental concepts, the Categories – plus two more: the concepts of space and of

time (§7). The functions Kant assigns to these concepts and their roles in guiding sub-personal

sensory-perceptual synthesis and in enabling explicit, self-conscious cognitive judgments are diagrammed for clarity in an Appendix: ‘Kant’s Cognitive Architecture’ (§13). Next I introduce

Kant’s semantics of singular, specifically cognitive reference (§8), which is required for experience

or knowledge in any non-formal domain, such as that of spatio-temporal particulars (§8.1). After

stating (what I call) Kant’s Thesis of Singular Cognitive Reference (§8.2), I specify a set of five

cognitively quite distinct activities and achievements, crucial to both empirical knowledge and to

epistemology (§8.3).

Having made these preparations, I recount Kant’s constructive strategy in the Critique of Pure Reason (§9), beginning with his (express) methodological constructivism (§9.1) and the four (generic)

steps involved in the constructivist strategy (§9.2). One important point is Kant’s indication of

the two-fold use of the Categories, in sub-personal sensory-perceptual synthesis, and also in any

explicit judgments we make about whatever we perceive or experience (§9.3). I then review

briefly Kant’s lead question (§9.4), his most basic inventory of our cognitive capacities (§9.5) and

his main constructive epistemological (or transcendental) question (§9.6). Answering that question requires addressing five Critical sub-issues (§9.7). With Kant’s agenda thus stated and summarised, I then synopsise the structure of Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason (§10), focussing on his ‘Analytic of Concepts’ and ‘Analytic of Principles’. For clear conspectus, this structure and its use of

Kant’s inventory of basic formal features of our cognitive capacities is tabulated (§14). I then

conclude briefly, indicating the aims and scope of this reconstruction of Kant’s construction of

the Critique of Pure Reason (§11). (An Appendix begins with §12, containing two diagrams of the

Aristotelian Square of Logical Oppositions.)

2

KANT’S INITIAL CLUES.

Hume awoke Kant from his ‘dogmatic slumbers’ (Prol. 4:260) by making clear that our mere possession of concepts does not and cannot suffice to use those concepts in any genuine, legitimate

cognitive judgments.

2.1 Hume’s negative point was sharpened by Tetens (1777; cf. GS 28:57), who introduced this

technical terminology to mark a key issue:

© 2019 Kenneth R. WESTPHAL; ALL rights reserved.

2

Work in progress; comments & critique welcome!

�Tetens: To ‘realise’ a concept or principle is to demonstrate – to point out, to hand over, to ostend

– at least one proper instance of that concept or principle.

However poorly Tetens may have fared with that innovation (GS 28:57), this task is exactly

Kant’s undertaking in the Critique of Pure Reason: To specify that, and how, a priori concepts and

principles can be ‘realised’ by identifying and ostending proper instances of them, and to distinguish those legitimate cognitive uses from other concepts, principles or illicit usage which cannot

be so realised. About this latter group Kant then inquires whether or how they may indirectly

serve legitimate cognitive or moral aims.

Most concepts are classificatory: they classify features or characteristics of particular individuals,

and in that way also those individuals which have or lack those features or characteristics. In this

regard, concepts are inherently general; they may be general in the extreme, such as ‘particular

individual’, ‘event’, ‘relation’, ‘feature’; or they may be very specific, such as ‘Prussian blue spot

on the dusty periwinkle blue petal of a globe thistle’ or ‘Streptomyces lavendulae avirens’ (NRRL B16576).2 Yet regardless of how specific a concept or classification may be, in principle it admits

of further speciation or sub-division; there are no infimae species (A655–6/B683–4).

Regarding empirical concepts, no matter how thoroughly we may describe or specify spatio-temporal particulars, of whatever kind or scale, whether there be no such particulars, only one or

perhaps several is an entirely distinct issue. In principle and in practice, conceptual specificity

does not suffice for unique designation of any one spatio-temporal individual. This point Kant

makes against Leibniz in the ‘Amphiboly of the Concepts of Reflection’, by appeal to two drops

of rain, as qualitatively identical as one may wish in size, shape or chemical composition, which

nevertheless are distinct, particular individuals insofar as they occupy distinct regions of space

(A263–4/ B319–20).

To ‘realise’ any empirical concept one must locate and identify at least one representative example. That is an empirical, not a philosophical, task; no other kind of justification or ‘deduction’ of

empirical concepts is possible, nor is any other required (A84–5/B116–7). The philosophical

problem concerns a priori concepts: Can they be ‘realised’? Can we identify and localise relevant,

proper instance of any a priori concept? If so, of which a priori concepts, which instances, and

how so?

Insofar as we may conceive and construct objects of pure reason, as in mathematics or axiomatics, the conceptual specification and construction of that object suffices for its unique, particular

identity, identification and individuation (A263–4/B319–20). Concerning the divine, the world as

a whole or the infinite divisibility of matter, we consider concepts or principles which purport to

be about particulars which (or whom) we do not construct conceptually, nor intuitively; neither

can we locate or localise these purported individual empirically. In principle, these concepts and

their associated principles cannot be ‘realised’ on theoretical grounds.

2.2 Philosophical Reflections on Sub-Personal Cognitive Processes? The problem confronting Kant’s task

2

For many such examples, see Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, 2nd ed. (Springer, 2001–2012), 5 vols. The

indicated code is used by the USDA’s Mycotoxin Prevention and Applied Microbiology Research Unit, at the

National Center for Agricultural Utilization Research in Peoria, Illinois (USA); now using the acronym ‘ARS’

(Agricultural Research Service), no longer ‘NRRL’ (Norther Regional Research Laboratory). Above I said ‘most’

concepts are classificatory so as avoid quibbles about whether, e.g., logical constants, proper names, or our

understanding of either, count as ‘concepts’.

© 2019 Kenneth R. WESTPHAL; ALL rights reserved.

3

Work in progress; comments & critique welcome!

�of ‘realising’ our most basic a priori cognitive concepts, the categories, is this:

That which is presupposed in any and all knowledge of objects cannot itself be known as an

object. (KdrV A402)3

This problem also gives Kant’s clue: To determine whether, and if so how, our most basic a priori cognitive concepts are necessary for us to be able to experience, discriminate, identify or

know any particular object (or event) at all.

3

CONCEPTS A PRIORI?

It may seem that Kant too quickly and confidently presumes there are a priori concepts, and that

we, of all finite creatures, have some. However, Kant is as incisive as he is brief about the key

point. Regarding his account of the concept of causality Kant acknowledges that

It might seem indeed as if this were in contradiction to all that has been said on the procedure

of the human understanding, it having been supposed that only by perception and comparison

of many events repeatedly and uniformly following preceding appearances are we led to the

discovery of a rule according to which certain events always follow certain appearances, and

that thus only are we enabled to form for ourselves the concept of cause. If this were so, that

concept would be empirical only, and the rule which it supplies, that everything that happens

must have a cause, would be as contingent as the experience on which it is based. The universality and necessity of that rule would then be fictitious only and devoid of any true and universal validity; it would not be a priori, but founded on induction only. (KdrV A195–6/B240–1)

The view Kant contradicts is standard empiricist doctrine, classically formulated by Hume’s concept empiricism and his view that our beliefs about causal relations are based on customary associations. The empiricist view is that we develop a concept of causality from observing particular

causal relations. Note that two principles are required by this (alleged) process. Observing particular causal relations involves using the principle that for the same kind of event there is the

same kind of cause. This may be called the ‘particular’ causal principle. The ‘general’ causal principle is that for each event there is some cause or other. This principle specifies the general concept of causality. According to standard empiricist doctrine, we obtain this general concept and

general principle of causality on the basis of experiences which witness (apparent) instances of

the particular causal principle.

Kant agrees with Hume that knowledge of particular kinds of causal relations, i.e., knowledge of

instances of the particular causal principle, must be based on repeated experiences with events

and their causes. Kant denies, however, that such experiences can generate the general concept

or principle of causality. Indeed, he argues that we cannot experience or identify particular kinds

of causal relations without presupposing and using the general concept and principle of causality!

To understand why, follow Beck (1978, 121–9) back to Hume’s study (T 1.4.2.20).

Hume begins his account with the alleged obvious facts of experience, that we experience sensory ‘impressions’, fleeting appearances, each of which is exactly what it appears to be and nothing more. Hume finds that our belief in ‘the continued existence of body depends upon the coherence and constancy of certain impressions’. However, he recognises that impressions are not

nearly coherent nor constant enough to generate such a belief. Our experience and memory tell

us nothing about unobserved objects, and we frequently experience only events which we regard

3

Translations are my own; they diverge from published translations mostly stylistically.

© 2019 Kenneth R. WESTPHAL; ALL rights reserved.

4

Work in progress; comments & critique welcome!

�as effects of causes we have not witnessed, such as the knocking on the door being caused by

someone on the other side of the door, whom we do not otherwise perceive as s/he knocks.

These difficulties required Hume to distinguish between the existence of objects and the existence of perceptions, despite the (alleged) fact that this distinction ‘has no primary recommendation either to reason or the imagination’ (T 1.4.2.47). Nevertheless, this distinction is required by

… reflection on general rules [which] keeps us from augmenting our belief upon every increase in

the force and vivacity of our ideas. … ‘Tis thus the understanding corrects the appearances of

the senses, and [e.g.] makes us imagine, that an object at twenty foot distance seems even to the

eye as large as one of the same dimensions at ten. (T 1.3.10.12).

In brief, the general concept and principle of causality is used in generating and correcting our

experiences of particular causal relations. The problem is that on purely statistical grounds, as

Hume recognised, we much more often experience either a cause or an effect in isolation, but

not both in relation. Each time we witness only one but not both members of a (putative) causeeffect pair, this would (by customary empiricist habituation) weaken any belief in that putative

cause-effect relation. This problem in data collection and consequent habit formation is so pervasive we would never be prompted to suppose that each event has some cause(s). Consequently, on Hume’s empiricist account of concept acquisition by association, we never should

develop the concept of cause at all – not even the bare Humean idea of ‘cause’ as 1:1 correlation

of paired event types.

This is a prime instance of Hume’s acumen and allegiance to common sense overriding the absurdities of his own abstruse philosophical reasoning. He believes as much as the vulgar in persisting physical objects; yet when he cannot justify this belief by means of his principles, he distorts his principles to fit. Kant, very much to his credit, distinguishes the two principles of causality, and recognises that the real problem is not one of correcting our experiences of causal

relations, but rather is one Hume never imagined, the problem of distinguishing events and objects within the uniformly successive apprehensions (sensory intake) of experience.

This issue regarding the general concept of causality is not isolated; it is fundamental: Hume’s

problem with personal identity is matched by problems with the identity of any physical object

and its very concept (‘body’, in Hume’s parlance), and with the concepts of ‘space’, ‘spaces’,

‘time’, ‘times’ and ‘word’ – in distinction to flatus vocii or mere noisy utterances. All of these key

concepts, their acquisition and their use Hume can only assign to our ‘imagination’, but of our

imagination Hume can provide no specifically empiricist account; that account is exhausted by his

inventory of sensory impressions and ideas (the two species of ‘perceptions’), the copy principle

and the three (purported) laws of psychological association. Unlike his followers, in the Treatise

Hume identifies why and how those empiricist principles are insufficient (Westphal 2013a, cf.

Turnbull 1959).

Now, to prove that (e.g.) the concept of causality is not only a priori, but to give some definite

sense of its legitimate cognitive use and to show that and how it is a condition for the possibility

of any integrated self-conscious human experience, is a transcendental task, executed in Kant’s

Transcendental Analytic, culminating in the Analogies of Experience. Understanding how so requires considering what Kant calls perceptual syntheses, which are far more basic than Hume’s

purported ‘customary associations’ of sensory impressions or ideas; they are known today in

© 2019 Kenneth R. WESTPHAL; ALL rights reserved.

5

Work in progress; comments & critique welcome!

�neuro-physiology of perception as ‘the’ binding problem(s).

4

SENSORY BINDING PROBLEMS – i.e.: FORMS of PERCEPTUAL SYNTHESIS:

Amongst the host of problems now called ‘the’ binding problem are these issues regarding sensory-perceptual synthesis and, ultimately, attention and judgment:

1.

Amongst all concurrent sensations, how are any specific sensations distinguished and

grouped together as sensations of any one particular?

2.

Amongst all succeeding sensations, how are any specific sensations distinguished and

grouped together as sensations of that same particular?

3.

Amongst all concurrently perceived sensible qualities or features, how are any specific qualities or features distinguished, grouped together and identified (recognised) as qualities or

features of any one particular?

4.

Amongst all succeeding perceived sensible qualities or features, how are any specific qualities or features distinguished, grouped together and identified (recognised) as qualities or

features of that same particular?

These issue arise because sensations do not, as it were, bind themselves together (clump) to

form percepts, nor do percepts bind themselves together (clump) to form perceptual episodes.

These issues arise within each sensory mode, and they arise across our sensory modes. They arise

sub-personally at a (merely) sensory level, so that we may also be apperceptively (self-consciously) aware of our merely apparent surroundings. They also arise at this apperceptive level of

our noticing, recognising or identifying individuals and events in our surroundings, exhibiting

whatever features, relations or changes they do.

These points about sensory-perceptual integration hold independently of Hume’s (official) sensory atomism, and they hold independently of the error of regarding sensations as themselves

objects of our self-conscious awareness, which typically they are not. Kant is thoroughly non- and

anti-Cartesian in these, as in many other regards (Westphal 2007): He recognises that our explicitly self-conscious experience is only possible for us on the basis of a rich host of sub-personal

cognitive processing, which Kant assigns to the ‘transcendental power of imagination’, including

his account of the three-fold synthesis of perception (cf. below, §9.3). Though he omitted most

of that account in the second edition, he did not rescind the account (Westphal 2004, §§22, 23).

Kant examines issues of ‘origins’, ‘sources’ or ‘processes’ involved in various aspects of human

cognition, though always in order to properly pose issues of cognitive content and validity, i.e.:

justification. His first readers – and not only they – were not so subtle and were confused by

Kant’s complex text.

The key point for now is that these binding problems pose the question, neglected by Hume,

but pursued by Kant: How can we distinguish and identify persisting individuals and concurrent

events within our surroundings amidst the continual influx of new sensory stimulation(s)? Kant’s

answer begins at the opposite pole, with his clue to our most fundamental concepts, the categories, rooted in our most basic formal aspects of judging. These most basic concepts must be

such as to guide sufficiently accurate and reliable sensory integration so that we can become

aware of anything so much as appearing to occur before, during or after anything else appearing

(to us) to occur.

© 2019 Kenneth R. WESTPHAL; ALL rights reserved.

6

Work in progress; comments & critique welcome!

�5

ARISTOTLE’S LOGIC: COMPLETE & EVER SO USEFUL.

For good reason, we now know, Kant regarded Aristotle’s logic as profoundly important, not

only for logic, but also for understanding and assessing cognitive judgments. The set of logical

oppositions represented in the traditional Square of Opposition suffices to specify the logical use

of ‘none’, ‘some’, ‘all’, ‘not’; affirmation, negation, disjunction, conjunction; and for hypothetical

and disjunctive as well as categorical syllogisms. Using these logical constants and quantifiers,

together with pairs of sentences or propositions, it is easy to generate Aristotle’s paradigmatic

syllogisms, including both modus ponens ponendo and modus tolens tolendo, i.e., disjunctive syllogism

plus negation elimination (Patzig 1969; Kneale & Kneale 1971, 72–3; Parsons 2017). The validity

of conversion of terms is also a straight-forward corollary of the logical relations represented by

this square. Taken together, Aristotle’s syllogistic logic is in the technical sense complete, because

every valid argument which can be expressed in his logical system can be deduced within his system of deduction, thus ‘every semantically valid argument is deducible’ (Corcoran 1974).4

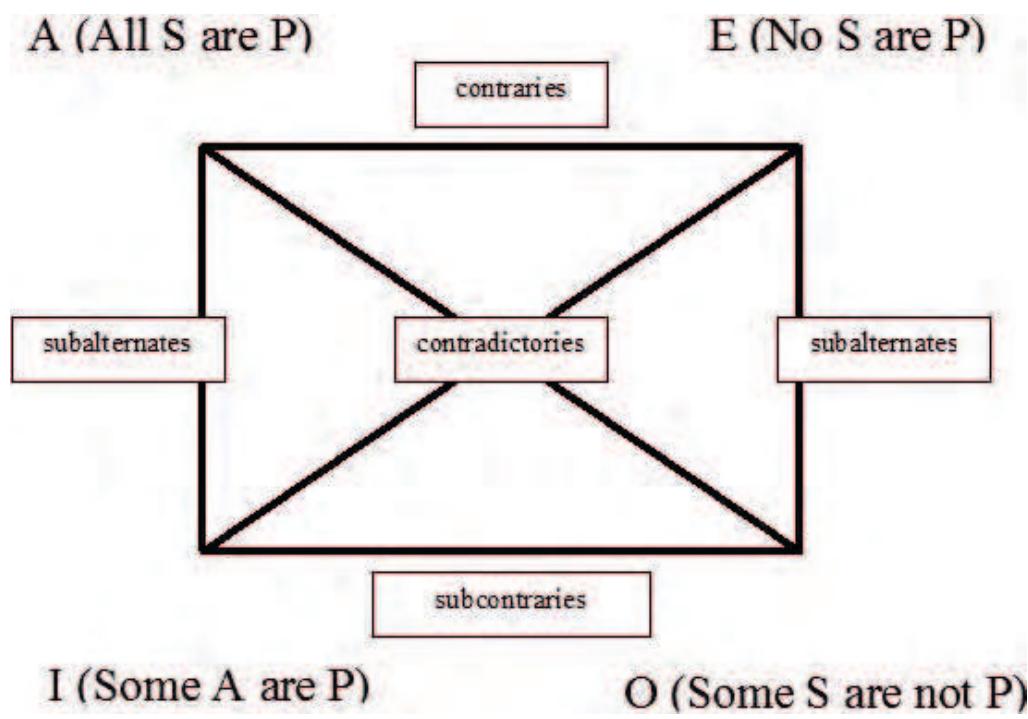

5.1 The Square of Categorical Oppositions:

5.2 Cognitive Use: Taxa & Classification. Aristotle’s logic has been rehabilitated by logicians,

though it is a very general and not an especially ‘strong’ logic. Epistemologically, however, its

very generality is crucial, also because it suffices to formulate genus/species reasoning and classification, which are fundamental to human experience, perception and empirical knowledge. Indeed, Kant was right to regard Aristotle’s logic as fully ‘general logic’ (A53–4/B77–8). The additional ‘strength’ of other formal systems of interest to technical logicians is all gained by additional semantic or existence postulates (or both), all of which are non-formal. All such ‘stronger’

logistic systems are less general; they are specific logics designed for specific domains, such as

Frege’s specifically mathematical logic (Wolff 2009b). It is important yet not surprising that Aristotle’s logic comports very well with contemporary ‘mental files’ or ‘mental models’ approaches

in cognitive sciences (Lopez-Astorga 2016, 2017). Indeed, Kant’s cognitive architecture and theory has much to offer contemporary cognitive science, which has yet to avail itself fully of

Kant’s Critical resources (Brook 1994, 2016).

4

A modern diagram of the traditional Aristotelian square of opposition is presented in Parsons (2017), §1; a

mediaeval diagram in Reisch (1504), 2.3.5 (1535, 153); Frege (1879) derives and displays it in „Begriffschrift“, §12.

It can be presented perspicuously using Venn diagrams. (Some examples are below, §12.)

© 2019 Kenneth R. WESTPHAL; ALL rights reserved.

7

Work in progress; comments & critique welcome!

�6

FORMAL ASPECTS OF JUDGING.

With great acuity, Michael Wolff (2009a, 2017) has identified, reconstructed and corroborated

Kant’s grounds for holding that his table of twelve formal aspects of judgment is complete, and

that Kant is correct that this basic Aristotelian logic is both fundamental and general. These

functional aspects typically work together in any actual judgment. As in Kant’s example, ‘This

body is metal’ (A69/B94), sensory perceptions are subsumed under the concept ‘body’ as

designating this perceived particular, now made subject of the predicative judgment that it is metal. Once identified as a metal body, one may infer other characteristics it has, based on one’s

conceptual repertoire of metallurgy (however commonsense or technical) and more generally of

bodies – such as their divisibility, and in the case of many metals, their malleability, their conductivity (of heat, sound or electricity) or their susceptibility to oxidation (rust). Kant’s ‘qualitative’

use of a concept in judging is non-predicative and referred directly to the perceived particular(s),

identifying it (or them) as subject(s) of one’s judgment. His ‘quantitative’ use of a concept is

predicative, ascribing some feature to that (or to those) particular(s) one has identified, indicated

and designated by the first (mediating) use of a concept. Kant’s ‘relative’ or relational use of a

concept in judgment is only mediately related to the object(s) judged, but is non-predicative; it is

cognitively significant insofar as it affords further inferences (subsumptions) regarding that (or

those) particular(s). Kant’s ‘modality’ pervades each of these aspects of judging, regarding both

how one ascribes features to, or denies them of, those particulars one judges, and one’s use of

evidence for, or one’s confidence in those ascriptions. (Their accuracy or justifiedness are further

issues not directly relevant to these formal aspects of judging.) Kant does not treat negation

truth-functionally, which affords him a distinction between denials of predications to some particulars within some sphere or range of relevant features; it makes sense to say of some bodies

(and some fluids) that they are colourless rather coloured in one or another way. It is quite a

cognitively distinct judgment (A71–3/B96–8) to deny that numbers can be coloured or colourless

(an ‘infinite’ negative judgment), whereas numerals may be. However dispensable singular or infinite judgments may be to syllogistic logic, they are crucial to cognition (and so to epistemology).

With regard to quantity, judgmental use of a concept may be universal, particular (some) or singular (individual); with regard to quality, judgmental use of a concept may be affirmative, negative or infinite; with regard relation, judgmental use of concepts or (sub-)judgments may be categorical, hypothetical or disjunctive; with regard to modality, judgmental use of concepts may be

problematic (tentative), assertoric or apodictic. These remarks are merely summary; Kant’s evidence for these theses is intricate and requires the care Wolff devotes to it. My sole concern is to

use these brief indications to suggest, in the next section, how Kant can use these clues about

formal aspects of judgments to devise a counterpart table of fundamental concepts, the categories.

7

FROM ASPECTS OF JUDGING TO JUDGING PARTICULARS: TWELVE CATEGORIES, PLUS TWO:

THE CONCEPTS OF SPACE & OF TIME.

Kant’s advance from his twelve of aspects of judgment to his twelve categories is expressly a

step away from general logic to a special logic, which he calls ‘transcendental logic’. It concerns

the kinds of judgment, including classification, differentiation and conditionalisation required to

identify, distinguish, track and classify sensed individuals in our surroundings. To do so requires

not only the twelve categories, but also the two key concepts from the Transcendental Aesthetic,

the concepts of ‘space’ and of ‘time’, each of which is required to identify any region of space

© 2019 Kenneth R. WESTPHAL; ALL rights reserved.

8

Work in progress; comments & critique welcome!

�and any period of time in which various individuals are perceived, how they are arranged, whether or how they change (either qualitatively or locally), and quite literally how and where we

stand with regard to them, when- and wherever we do so. Kant’s strategy is to begin with formal

functions exercised in judging, to consider how these functions indicate our most fundamental

concepts by which we can characterise, classify and individuate anything we might sense and

identify whatsoever. His entire ‘Analytic of Concepts’ and ‘Analytic of Principles’ are devoted to

gradually, carefully specifying our most basic, general concepts so as to be able to ‘realise’ them in

Tetens’ sense by identifying actual spatio-temporal, perceptible, causally active, interacting particulars (of whatever kinds or scale), which instantiate our basic conceptual categories. Accordingly,

his first step, so as first to identify the categories, is to consider how those twelve functions of

judgment can be specified so as to identify the most general concepts which can be in principle

brought to bear upon an on-going, incoming spatio-temporal manifold of sensory intake, which

always and by default fills our sensory field, so to speak, edge to edge (A77–8/B103). The categories Kant identifies must afford solutions to the sensory binding problems noted above (§4).

The most direct role for the categories in this regard is to guide – to structure – various forms of

sensory synthesis by which alone perception is humanly possible (A78–9/B104). Kant contends

that the very same functions which integrate or unify representations (including concepts and

logical relations) within judgments, also function to integrate or unify representations within any

empirical intuition (A78–9/B104–5). An empirical intuition integrates some plurality of sensations and contributes to localising their source within our (in principle, perceptible) surroundings. Likewise, a plurality of empirical intuitions are integrated into any one momentary percept (or

image, Bild; A120–1) of any one particular in our environs. And yet again, some plurality of percepts is likewise integrated through some period of time and within some region of space so as

to afford any one, continuing perceptual episode during which we perceive any one individual.5

These syntheses or integrative functions not only identify some one particular, they also must

differentiate that particular from others. This is part of why disjunctive judgments which are ‘infinite’ in form have an important cognitive role: perceptual judgments are discriminatory, distinguishing one particular from others, and distinguishing any of its manifest, observed changes from

causally possible alternatives to the manifest changes perceived particulars may exhibit.

Kant does not think the categories taken in their full generality suffice for these specific

cognitive-perceptual functions. His first claim is only that the same logical functions in judgment,

when taken in connection with an otherwise unspecified, incoming sensory manifold, suffice to

identify our most basic concepts, which again likewise fall into four groups of three categories

each. The quantitative categories are unity, plurality and totality; the qualitative categories are reality, negation and limitation (the counterpart to infinite judgments); the relational categories are

inherence and subsistence (or persistence, we might say), cause and effect and ‘community’ or

causal interaction; the modal categories are (im)possibility, (non)existence and necessity/contingency (A80/B106).

Having provisionally identified our most fundamental concepts, the categories, and suggested

that they can function by guiding (sufficiently) effective, reliable sensory-perceptual syntheses required to solve the binding problems noted above (§4), Kant embarks on his ‘Transcendental

Deduction’ of these pure categories of the understanding, which aims to show that these con5

Kant’s cognitive architecture is diagrammed in Westphal (2020*), §9; the diagram is included below for easy

reference (§13).

© 2019 Kenneth R. WESTPHAL; ALL rights reserved.

9

Work in progress; comments & critique welcome!

�cepts can, and can only, play the cognitive roles he here anticipates. This is not to claim that

these cognitive roles are fully fledged, that is, quite literally: fully specified; they are not! Central

to Kant’s aim in the Transcendental Deduction is that our most basic, a priori concepts may be

used to think whatever we like, so long as we avoid contradiction (Bxvi, n., cf. A220/B268), but

they can be used to know only insofar as we bring them to bear upon identifying and properly (if

approximately) characterising particular, sensed individuals. Setting aside mathematics, we human

beings are only able to identify and characterise specific, particular individuals by localising them

within space and time in our surroundings. Kant further argues that, as human beings, we are

only able to be aware of ourselves as being aware of anything so much as appearing to occur before, during or after anything else appears to occur, insofar as we identify and individuate, at least

approximately, some individual(s) we perceive in our surroundings. Only particulars substantial

enough for us to be able to identify, individuate and track them through some identifiable period

of time within some identifiable region of space are such that we can at all distinguish those particular from our perceptually experiencing them, and do so as we perceptually experience them.

This alone enables us to distinguish between our own bodily-perceptual comportment and the

particulars surrounding us which we perceive. These are strong claims, which anticipate much

which remains to be discussed.

Before continuing, note that Kant’s ‘deductions’ of the categories are in this regard complementary (B159): his ‘metaphysical’ deduction identifies the categories and their four main groups (‘titles’) by coördinating them with his Table of Judgments. His ‘transcendental’ deduction identifies the fundamental, i.e. categorial status of these concepts by identifying how they form the

necessary, sufficient minimum concepts required to integrate the merely logical self-referential

thought, ‘I think’ with any object-regarding thought about any particular which can be sensorily

presented to any self-conscious human being (B165). Kant expressly limits his transcendental

deduction to proving that the categories are in this regard necessary and sufficient. How they suffice is expressly the topic of Kant’s examination of the transcendental power of judgment in the

‘Analytic of Principles’ (B167). Before turning to Kant’s examination of these principles, consider first Kant’s insight regarding singular, specifically cognitive reference.

8

KANT’S SEMANTICS OF SINGULAR, SPECIFICALLY COGNITIVE REFERENCE.

8.1 Knowing Particulars. Recall (from §2.1) Kant’s clue from Tetens (1777), that any cognitively

legitimate use of a concept must ‘realise’ that concept by indicating at least one actual, relevant

instance of it. In exactly this regard Kant states in the Critique of Judgment:

…. all the categories, … can have no significance for theoretical cognition [i.e., empirical knowledge of particulars] at all if they are not applied to objects of possible experience. (KdU 5:484)

By ‘objects of possible experience’ Kant here means (at the least) that we properly use the categories in connection with objects we can experience, through which we can identify them. Kant

expressly argues that our categories only have cognitive significance insofar as they are referred

to particular objects, which requires of us human beings that our sensory intake presents particular objects to us. This cognitive significance accrues to the categories only insofar as they are

‘realised’ in and through human sensibility, which thus also restricts their cognitive significance to

the spatio-temporal domain of particulars which alone we can sense (A147/B187). In exactly this

regard, Kant anticipates Gareth Evans’ point regarding predication, not as a grammatical form,

but as a proto-cognitive act of ascribing characteristics to some (putative, localised, circum© 2019 Kenneth R. WESTPHAL; ALL rights reserved.

10

Work in progress; comments & critique welcome!

�scribed) individual, or to some aspect of one. Contra Quine, Evans concludes that:

… the line tracing the area of [ascriptive] relevance delimits that area in relation to which one or

the other, but not both, of a pair of contradictory predicates may be chosen. And that is what it

is for a line to be a boundary, marking something off from other things. (Evans 1975, CP

(1985), 36, cf. 34–7)

Evans’ point Kant makes at the end of the Transcendental Deduction by considering the example of coming to perceive a house we happen to intuit (sense) empirically:

If I thus e.g. apprehend the manifold of empirical intuition of a house and thus come to perceive

it, this is based upon the necessary unity of space and outward sensory intuition generally, and I

draw, as it were, its figure in accord with this synthetic unity of this manifold within space.

Even this very same synthetic unity, however, if I abstract from the form of space, … is the

synthesis of the homogenous in an intuition as such, i.e., the category of quantity, with which

that synthesis in apprehension (i.e., the perception) must fully accord. (KdrV B162)

Kant thus argues – and not only here – for what may be called his Thesis of Singular Cognitive

Reference. (This designation is my own.) It concerns the cognitive, and hence also the epistemological significance of identifying by locating those individuals to which we ascribe any features, by which alone we can know them and can claim to have knowledge of them. Kant’s Thesis distinguishes, repeatedly and emphatically, between the classificatory content (intension) of

concepts, and their further, specifically cognitive significance which they have and can have only

when Someone refers those concepts to particular(s) S/he has localised within space and time,

regardless of the kind, scale or quantity of these designated particulars, and regardless of whether

unaided sensory perception or instrumentally extended detection is required. Kant’s thesis may

be stated thus:

8.2 Kant’s Thesis of Singular Cognitive Reference:

Terms or phrases have ‘meaning’, and concepts have classificatory content (intension), as predicates of possible judgments, although in non-formal, substantive domains, no statement or proposition has specifically cognitive significance unless and until it is incorporated into a candidate

cognitive judgment which is referred to some actual particular(s) localised (at least putatively) by

the presumptive judge (a cognisant subject, S) within space and time. Cognitive significance, so

defined, is required for cognitive status (even as merely putative knowledge) in any non-formal,

substantive domain.

8.3 The Implications of that Thesis for Knowledge & Epistemology. Kant’s Thesis of Singular Cognitive

Reference, together with the three basic aspects of knowledge, i.e., belief, truth and justification,

justify these cognitive (hence also epistemological) distinctions between:

1.

Thinking some definite thought, or entertaining some definite proposition, statement or belief.

2.

Ascribing what one thinks, believes or judges to some localised, indicated (ostended) particular(s).

3.

Ascribing accurately or truly what one thinks, believes or judges to those indicated particular(s).

4.

Justifiedly ascribing accurately or truly what one thinks, believes or judges to those indicated

particular(s) (where the relevant justification is cognitive).

© 2019 Kenneth R. WESTPHAL; ALL rights reserved.

11

Work in progress; comments & critique welcome!

�5.

Ascribing accurately or truly what one thinks, believes or judges to those indicated particular(s) with sufficient cognitive justification to constitute knowledge.

Each of these (proto-)cognitive activities or achievements allows significant latitude to be specified to

domain-specific kinds of inquiries, evidence, judgments, explanations or precision. Only the last (5.)

counts as knowledge; (4.) may include a broad range of reasonable belief. Note, however, that mere

logical possibilities only meet the first (1.) requirement. Hence they have neither any truth-value nor

any justificatory status. Hence they lack altogether even proto-cognitive standing. Thus they do not

and cannot serve to ‘defeat’ or undermine the justification or the accuracy of any otherwise adequately justified, sufficiently accurate judgment. Justificatory infallibilism is thus strictly and in principle irrelevant to the non-formal domain of empirical knowledge (and also morals).

9

KANT’S CONSTRUCTIVE STRATEGY IN THE CRITIQUE OF PURE REASON.

9.1 Kant’s Methodological Constructivism. Kant’s method is expressly constructivist (A707/B735;

O’Neill 1992). Constructivist method is a method for identifying and justifying concepts or principles; it is consistent with realism about particulars within the domain(s) of those concepts or

principles.

9.2 The Constructivist Strategy has four steps:

Within some specified domain,

1.

Identify a preferred domain of basic elements;

2.

Identify and sort relevant, prevalent elements within this domain;

3.

Use the most salient and prevalent such elements to construct satisfactory principles or accounts of the initial domain, by using

4.

Preferred principles of construction.

In §10 I exhibit how Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason uses exactly this constructivist strategy. To prepare for that, I review and highlight some main points from the preceding sections about Kant’s

basic elements and problems to be addressed and resolved. These pertain to how Kant posed

and addressed fundamental cognitive/epistemological questions about how can we identify any

domain whatsoever, its members and relevant principles?

9.3 The Two-Fold use of the Categories: sub-personal perceptual synthesis, explicit judgments. Kant

expressly indicates a dual, ‘two-fold use’ of the Categories, first in ‘figurative synthesis’, second in

explicit cognitive judgments:

The same function which provides unity to diverse representations in a judgment, also provides

the mere synthesis of diverse representations in an intuition. Thus the same understanding, indeed through the same action, by which it in concepts through analytical unity produces the logical form of a judgment, also provides through synthetic unity of the manifold in intuition as

such within its representations a transcendental content, according to which they are called pure

concepts of the understanding, which pertain a priori to objects, which cannot be achieved by

general logic. (KdrV A79/B104–5; underscoring added, as also just below – KRW)

… the POWER OF IMAGINATION is a capacity to determine sensibility a priori, and its synthesis

of intuitions according to the categories must be the transcendental synthesis of imagination,

which is an effect of the understanding upon sensibility and [is] its first application (and as such

the ground of all others) to objects of those intuitions possible for us. As figurative, this [imagi© 2019 Kenneth R. WESTPHAL; ALL rights reserved.

12

Work in progress; comments & critique welcome!

�nation] is distinct to the intellectual synthesis merely by understanding, altogether without imagination. Insofar as the imagination is spontaneity, occasionally I call it the productive imagination and thus distinguish it from the reproductive [imagination], the synthesis by which is subject only to empirical laws, namely, those of association …. (KdrV B152)

… the synthesis of apprehension, which is empirical, must necessarily accord with the synthesis

of apperception, which is intellectual and is contained entirely a priori in the category. It is one

and the same spontaneity, which there under the name of IMAGINATION, here [under the name]

of understanding, introduces connection in the manifold of intuition. (KdrV B162n.)

Kant thus uses his account of formal aspects of logical judgment, the Categories, the two concepts of ‘space’ and of ‘time’, and an unspecified, continuing sensory intake (manifold) to try to

specify necessary and sufficient sub-personal cognitive functions and functioning required for us

to be able to be aware of ourselves as being aware of any putative objects distinct to ourselves

and our sensory-perceptual experiencing them. His lead question may be stated in these terms.

9.4 Kant’s Lead Question:

How is it possible, what conditions must be satisfied, such that we finite cognisant human beings

can integrate sensory intake over time – and through space – so as to distinguish between whatever we may perceive, experience or know in our environs from our perceiving, experiencing or

knowing it (or them)? (Guyer 1989)6

9.5 Kant’s most Basic Inventory:

1.

Two forms of sensory receptivity: We homo sapiens sapiens can only respond to spatial & temporal stimuli.

2.

Two a priori concepts for locatability and discriminability: the concepts of ‘space’ & ‘time’;

3.

Twelve formal aspects of judging: the Table of Judgments. (Wolff 2009b, 2017)

4.

The logical subject of any judging: the ‘I think’ which can (and must be able to) accompany

any of my (one’s own) self-conscious states or episodes.

5.

An unspecified sensory manifold.

9.6 Kant’s Constructive Epistemological (Transcendental ) Question: How can those abstract formal aspects of our cognitive capacities be specified so as to make possible for us any self-conscious experiential episode in which anything appears to us to occur before, during or

after anything else appears to us to occur?

9.7 That question can only be answered by resolving these five issues:

1.

Within the ever-successive, continuing intake of current sensory stimulation (sensory manifold), how can we discriminate which particulars (distinct to ourselves) are located where

and when, and what changes they undergo?

2.

We can only be self-conscious (apperceptive) by distinguishing from ourselves some particulars in our surroundings, so as to identify ourselves as perceptive in being perceptually aware

of those particulars.7

6

Here I restate Guyer’s point, rather than quote directly.

More specifically, we can only apperceive ourselves as being aware of so little as some apparent changes appearing

to occur before, during or after other apparent changes. (This is one way to restate the first premiss of Kant’s

7

© 2019 Kenneth R. WESTPHAL; ALL rights reserved.

13

Work in progress; comments & critique welcome!

�3.

We can only perceive our surroundings if we can and do discriminate those changes within

the sensory content of our experience which are due to our own perceptual(-motor) behaviour from those changes within the sensory content of our experience which are due to relatively stable perceptible particulars and their locations, behaviour and (causal) interactions.

4.

Each of these cognitive achievements (1.–3) requires that we can and do (sub-personally)

solve the perceptual binding problems (§4) = perceptual synthesis, effected by productive

transcendental imagination (§9.3).

5.

Each of these cognitive achievements (1.–3.) also requires that we can and do satisfy the requirements for singular cognitive reference, and make reliably – if implicitly and approximately – the kinds of cognitive distinctions involved in Kant’s Thesis of Singular Cognitive

Reference (§8).

How extensive or precise our knowledge may be is entirely an empirical matter. The central

synthetic principle Kant justifies a priori is that we human beings can only be aware of ourselves

as being aware of some events appearing to occur before, during or after other apparent events,

if in fact we perceive and identify at least some spatio-temporal, causally structured particulars

distinct to ourselves within our surroundings.

10 THE STRUCTURE OF KANT’S CRITIQUE OF PURE REASON.

These remarks on the structure of Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason should be considered together

with the chart below, ‘Kant’s Inventory of Basic Formal Features of our Cognitive Capacities’

(§14).8 The chart focusses on Kant’s ‘Analytic of Concepts’ and ‘Analytic of Principles’; it takes

for granted that we are sensitive (receptive) only to spatio-temporal sensory stimulation, and that

we have two a priori concepts, those of ‘time’ and of ‘space’, which we can arbitrarily delimit

(specify, determine) so as to identify and distinguish various regions of space and periods of

time, so as to identify various particulars we experience and those occasions on which and regions in which we experience them.

The Chart begins with Kant’s twelve formal functions exercised in judgment. These functions,

considered in connection with our otherwise unspecified spatio-temporal manifold of on-going

sensory intake, enables Kant to identify our most fundamental concepts, the Categories, listed in

the second column from the left. Kant’s ‘Schematism’ of the Categories is the first chapter of his

‘Analytic of Principles’. It only considers what further specification the Categories require in order to be brought to bear upon, and thus to be able to be referred to, temporal phenomena.

Kant noted in his margin that the Schematism also requires considering the further specification

the Categories require in order to be brought to bear upon, and thus to be able to be referred to,

spatial phenomena. As noted above (§8), Kant concludes the B-edition Deduction with an

example of perceiving a house, including identifying its spatial form and size using the Category

of quantity. Kant’s treatment of these schemata is, by design, highly abstract: this chapter only

concerns what further semantic specificity (intension) must be supplied to the Categories so that

‘Refutation of Idealism’; likewise it is the minimum necessary interpretation of Kant’s claim that the analytic unity

of apperception is only humanly possible on the basis of our achieving at least some humanly recognisable synthetic

unity of apperception, which itself requires our achieving at least some humanly recognisable synthetic unity of

perception of particulars other than ourselves.

8

In this connection readers may also wish to consider the outline formatting of Kant’s Table of Contents to KdrV

in Pluhar’s (1996, viii–xvi) translation.

© 2019 Kenneth R. WESTPHAL; ALL rights reserved.

14

Work in progress; comments & critique welcome!

�they can in principle be referred to spatial and to temporal phenomena in general. Still further

semantic specification (classificatory specificity, intension) must be supplied to be able to refer

the Categories to any particular (specific, individual) spatio-temporal phenomenon. So far as this

semantic specificity can be identified by philosophical (transcendental) reflection, Kant does so

in ‘The Principles of the Understanding’. These are listed in the final, right-hand column of §14.

Kant’s ‘Axioms of Intuition’ directly recall his example of perceiving a house, which requires that

we can and do identify and discriminate particular individuals within specifiable, delimited regions of space during specifiable, delimited periods of time. This holds both regarding the

spatio-temporal region occupied by any particular (of whatever kind or scale), and the spatiotemporal region which provides and enables us to identify the occasion on and context within

which we identify those particulars, and our relation(s) to them. The ‘Anticipations of Perception’ concern a constraint upon our perceptual capacities, that any particular we can experience,

perceive or identify must exhibit some perceptible features exhibiting some sufficient intensity

within some sufficiently extended spatial region that we can respond to it by sensing it at all.

Kant fully expects that particulars satisfy such conditions for their human perceptibility due to

their (i.e.: our) material constitution, by which the causal interactions which undergird and enable

our sensory-perceptual processed can occur and be registered by us (cf. Edwards 2000). Those

two sets of principles Kant calls ‘mathematical’, in contrast to the ‘dynamic’ principles: the ‘Analogies of Experience’ and the ‘Postulates of Empirical Thinking’.

The ‘Analogies of Experience’ are indeed crucial to Kant’s whole Critical epistemology, for they

concern three fundamental causal principles by which we can identify and discriminate relatively

stable physical particulars, their locations, our location with respect to them, and the various

changes they undergo or produce (events), as well as the various changes we make in our own

bodily-perceptual comportment. One central point about these three principles was identified by

Paul Guyer (1987; cf. Westphal 2017a): we can only use these three principles conjointly, because

causal judgments are discriminatory; we can only identify any particular persisting insofar as we can

also identify that and how we alter our own position and attitude (literally) toward it, and insofar

as we can identify that persisting particular through whatever spatial changes currently transpire,

including distinguishing between merely local motions (rotations) from translational motions

(changes of location), so that we can distinguish between those features of any particular which

themselves persist, though they may pass from our view by various relative motions (rotations),

and those of its features which may currently undergo change. Our capacity and our exercise of

our capacity to discriminate between those changes within our sensory-perceptual experience

which are due to what is in, and what changes in, our surroundings, from those changes within our

sensory-perceptual experience which are due to our own bodily, motor-perceptual activity, requires that there are perceptible particulars, events and processes which we can identify and discriminate, however approximately. Yes, on the basis of his transcendental reflections upon the

very possibility of self-conscious human experience, Kant was aware of what is now known as

sensory re-afference, by which organisms monitor their own bodily changes, so as to compensate for it, so as to be able to perceive its surroundings, rather than merely to register changing

sensory stimulations (Brembs 2011). Kant stresses that it is our choice whether to view a house

top to bottom or vice-versa, left to right or vice-versa (A192–3/B237–8), or whether to look first to

the night horizon, then to the rising moon, then back to the horizon, or vice versa (B256–7). Kant

likewise stresses that some changes occur, and are perceived to occur (if we pay attention), regardless of our own bodily comportment: No matter when or how frequently we look at it, or

© 2019 Kenneth R. WESTPHAL; ALL rights reserved.

15

Work in progress; comments & critique welcome!

�look away, the ship sails further in whatever direction it is headed (until the captain decides, or

weather requires, otherwise) (A192/B237); water freezes as ambient temperature drops, regardless of our mere perceptual-motor observation (B162–3); and similarly in other cases – such as

the porter arriving at Hume’s door, bearing him a letter from London, via the local post office,

and thence via the avenues and walk-ways of the porter’s route to Hume’s apartment building,

then up the stairs Hume too uses, though he witnesses none of these as he hears and unfailingly

recognises the knock at the door (T 1.4.2.20). Hume’s empiricism cannot account for Hume’s

entirely commonsense and correct observations and judgments about his own immediate neighbourhood and abode.

I remark only briefly on Kant’s ‘Postulates of Empirical Thinking’, mostly to stress that they are

expressly transcendental principles (A219–20/B266–7), and so provide neither Kant’s account of

causal modalities, which are central to the Analogies of Experience, nor do they provide his full

account of cognitive modalities, especially as regards cognitive justification. This is wise on his

part: As noted in connection with his Thesis of Singular Cognitive Reference (§8), each of the

five distinct activities or achievements there identified allows considerable latitude to tailor them

to specific domains and kinds of inquiry; how and how best to do so is central to legal procedures, technical diagnostics, engineering and the various special sciences.

One core point throughout Kant’s ‘Dialectic’ may be put briefly. ‘Ideas of Reason’ are concepts

of complete totalities; they are each logically consistent, and synthetic, insofar as they are nonformal. (Logically consistent propositions formed with these concepts have logically consistent

negations.) Yet as (putative) totalities, we can ‘realise’ none of them in any referentially determinate, specific way by ostending their purported, proper instance(s). Hence they can only be used

to think, but not to know; they suffice for and afford only the first of the five proto-cognitive

activities indicated by Kant’s Thesis of Singular Cognitive Reference (§8): thinking a logically

consistent thought. Consider an important feature of Kant’s referential, cognitive and epistemological development of Aristotelian syllogistic. For formal logic, the existence suppositions built

into syllogistic logic are either irrelevant or defective. However, for cognition – knowledge – and

for epistemological theory of knowledge, those existence suppositions are important indicators

of the referential and so the existential requirements of knowing something, anything, about some

particular (of whatever kind or scale): localising that (or those) particular(s), so that one’s belief,

claim or judgment has any truth value (or value as an approximation), and has such a value which

Someone can assess. In this connection alone – this topical, and ostensive, referential connection:

Gegenstandsbeziehung – do the cognitively and epistemologically indispensable issues of cognitive

justification arise, and can they be assessed.

Here again Kant’s non-truth functional treatment of negation is cognitively and epistemologically significant: By example in the Dialectic and expressly in the ‘Discipline of Pure Reason’

(A789– 94/B817–22), Kant proscribes apagogic, indirect proof by disjunctive syllogism in any

case in which we cannot localise the required, claimed individual(s) purportedly in dispute. ‘Everything sleeps either restfully or fitfully’ – not so: not green ideas, nor anything inorganic. ‘Necessarily, the soul is either simple or compound’. So simple this issue is not: ‘simple’ and ‘compound’ are mutually exclusive, but to what aspects, features or individuals does either quasi-quantitative designation pertain, and how so? Until we answer this question definitely by realising either concept (term) by localising at least one relevant individual instance, we literally do not

know what we are thinking, talking or arguing about. The contrast between ‘simple’ and ‘com© 2019 Kenneth R. WESTPHAL; ALL rights reserved.

16

Work in progress; comments & critique welcome!

�pound’ is equivocal: A particular may be neither ‘compound’ (composed of parts) nor ‘simple’,

insofar as it is one, unitary, indivisible, and yet has a variety of aspects (not parts). This is the

breaking point of Hume’s account of abstract general ideas, of distinctions of reason and also of

concept empiricism (Westphal 2013). The logical law of bivalence holds de dicto, that is, with regard to propositions: only one of two logically contradictory propositions can be true. The logical law of excluded middle holds de re : nothing, no res, can both have and lack a feature or characteristic at the same time and in the same respect. These principles, and their domains of use,

must not be confused. Neither colour nor transparency pertain to numbers, though they do pertain to numerals (if we count black, white and shades of grey as ‘colours’). Only with regard to

objects of pure reason, Kant emphasises here again, does their purely conceptual specification suffice to construct their sole proper instances – in mathematics (A7115–9/B743–7). Without such

construction or ostensive demonstration of that uniquely specified individual, the concepts involved are mere thoughts, which may have no instances, several or perhaps by sheer luck and

happenstance only one.9 Until those concepts can be shown to be referentially, existentially nonempty, they are not even candidates for knowledge. Otherwise, such purported demonstrations

or disputes are merely argumentae ad ignorantiam.10

Kant’s own transcendental proofs regarding a series of specific formal and material (sensory)

conditions, which must be satisfied if any of us is to achieve apperception, turn on demonstrating that these conditions are necessary to any humanly possible apperceptive experience (A786–

9/B814–7). Here I have only sought to present Kant’s points of departure and constructive strategy for developing and assessing such proofs, though also to show how plausible they are by

exhibiting how much more fundamental they are than those issues or strategies familiar from

empiricism, rationalism, much of contemporary linguistic philosophy or most of contemporary

‘naturalised’ epistemology. The appeal to, and the search for, some sufficiently robust sense of

‘broad logical necessity’ has been inconclusive because the notion is too vague, or even self-contradictory: logical necessity holds within purely axiomatic systems; the desired ‘breadth’ comes

only with further, non-formal, hence substantive semantic and existence postulates, none of

which can be defined, justified or assessed purely formally. The relevant alternative concept is

‘synthetic necessary truth’, but few analytic philosophers have been bold enough to take this

concept seriously; see Toulmin (1949), Sellars (1978).11

9

Cf. Kant’s observation that the impossibility of a two-sided, rectilinear, planar enclosed figure is not a strictly logical

impossibility (A220–1/B267–8). As for Quine’s favourite example of a definite description, ‘the shortest spy’,

however grammatically definite it is, it may be logically (quantitatively) equivocal: ‘the shortest spy’ may be a

congenital twin, triplet or even quintuplet, all of whom are identical in stature and vocation. Specificity of

description (intension) does not suffice, of itself, for uniqueness of referent (deixis).

10

As for global perceptual scepticism, see Westphal (2004), §63. Very briefly, global perceptual scepticism requires

infallibilism about cognitive justification; Kant’s Thesis of Singular Cognitive Reference shows that, in principle,

infallibilism is irrelevant to any and all non-formal domains. The purportedly ‘global’ character of such scepticism

renders it an entirely transcendent, merely conceptual construct: As Kant expressly notes, the whole of perceptual

experience is not itself an object of perception (A483–4/B511–2). No wonder neither logic nor sensory evidence

can address global perceptual scepticism, but the mere logical consistency of the idea of global perceptual

scepticism only satisfies the first of the five proto-cognitive achievements distinguished by Kant’s Thesis of

Singular Cognitive Reference, and its mere logical consistency cannot bring so-called ‘global sceptical hypotheses’

into the non-formal domain of genuine empirical cognition (whether knowledge, guesswork or error).

11

C.I. Lewis (1929) argued for a host of synthetic a priori concepts and principles, but shied away from any that

would be necessary. For discussion of Lewis (1929) and of Sellars (1978), see Westphal (2010). The most fundamental synthetic necessary truths cannot be mere conventions; see Parrini (2009), (2010); Westphal (2017c).

© 2019 Kenneth R. WESTPHAL; ALL rights reserved.

17

Work in progress; comments & critique welcome!

�11 A BRIEF CONCLUDING WORD.

This overview aims only to clarity Kant’s key problems, resources, strategies and theses. Exactly

how and how well he justifies any of these points requires further, separate examination. Such

examination may, I hope, be more focussed, constructive and cogent – whether pro or contra – by

having Kant’s issues, aims and strategies in clearer view. Readers will have noticed my careful selection of themes and theses on which to focus. I have deliberately prescinded from Kant’s transcendental idealism, in large part to exhibit what, and how very much Kant achieves without appeal to his idealism12 – and yes, because I have argued elsewhere that he fails to justify that idealism, and further: he did not need that idealism to achieve his most important results, results

which deserve far better regard than they generally have had, especially amongst epistemologists.13

12

Without appealing at all to transcendental idealism, Kant soundly diagnoses the spurious debate about ‘freedom’

versus ‘determinism’ (of action), showing that it, too, is an argumentum ad ignorantiam, though this topic requires more

extensive discussion; see Westphal (2017b), (2020).

13

My first opportunity to draft these thoughts was by kind invitation of Porto’s 3I Seminar 2017–18: Imaginations,

Images, Imaginaries, sponsored by their research group: Aesthetics, Politics & Knowledge, organised by Alberto

Romele, Paulo Tunhas, Luca Possati & Armando Malheiro; sponsored by FCT Instituto de Filosofia da

Universidade do Porto (FIL/00502). I thank them for their generous invitation and lively discussion! Work on

this research is supported in part by the Boðaziçi Üniversitesi Research Fund (BAP; grant code: 18B02P3).

© 2019 Kenneth R. WESTPHAL; ALL rights reserved.

18

Work in progress; comments & critique welcome!

�APPENDIX.

12 THE LOGICAL SQUARE OF OPPOSITION.

12.1 A modern diagram of Aristotle’s Square:

12.2 Reisch (1504), 2.3.5 (1535, 153):

12.3 Gottlob Frege (1879), „Begriffschrift“, §12:

© 2019 Kenneth R. WESTPHAL; ALL rights reserved.

19

12.4 A recent version using Venn diagrams:

Work in progress; comments & critique welcome!

�13 KANT’S COGNITIVE ARCHITECTURE.

Thing in itself

?

{ (Considered in transcendental reflection on human sensibility,

|

or in moral reflection on human agency; B160 & note.)

?

|

Space & Time as forms of human intuiting.

The integration of our experiences

?

{ via intellectual synthesis by Transcendental

of spatio-temporal particulars is

f

Things as such

f

Sensations !

f

Power of Imagination; B160 & note)

guided, i.e., regulated, by immanent

use of Ideas of Reason (B670–96)

Space & Time as formal intuitions

f

! sensory !

(momentary/synchronic)

[ Percepts ] !

spatio-

!

intuitions

e

Affinity (associability)

of the sensory manifold

f

(diachronic)

! apperceptive experiences of

(‘Bild’: A120–1)

temporal objects & events.

wxe

=

3-fold per- / ceptual syn-

thesis (B103–5, A97–104)

e

e

(used by Transcendental Power of Imagination)

2-fold use of Categories

A

(Only these 2 Aspects

can be apperceived.)

:

Cognitive Judgments

(Principles)

wax

e

Ad

The CATE / GORIES

Transcendental Power of Judgment brings our Forms of

Judgment to bear upon our Forms of Sensory Intuiting,

(A79/B105–6, B152, 162 note)

Space & Time.

e

(used by Understanding)

{ Schematism*

(*Each Category is

further specified

by transcendental

imagination to link

to time (& space),

LOGICAL FORMS OF JUDGMENT

and so to spatio(acquired ‘originally’: KdrV B167,

temporal objects

Ak 17:492, 18:8, 18:12, cf. 7:222–3)

& events.)

Notes:

1. ! Arows indicate processes, roughly information processing channels. Their exact significance depends

upon their context (location, Verortung, transcendental topic) within Kant’s analysis.

} Braces link (comments) to particular features of the diagram.

2. Kant’s Transcendental Idealism only appears in the upper left corner, suggesting how it can be elided from

his positive account of our cognitive capacities.

{3. This diagram is from K.R. Westphal (2020*), ‘Kant’s Analytic of Principles’, M. Timmons & S. Baiasu,

eds., Kant (London: Routledge; chapter 8), §9. Used by permission for ease of reference and review purposes

(only).}

© 2019 Kenneth R. WESTPHAL; ALL rights reserved.

20

Work in progress; comments & critique welcome!

�14 KANT’S INVENTORY OF BASIC FORMAL FEATURES OF OUR COGNITIVE CAPACITIES

This inventory is discussed above, §§9.4–9.7, 10. Along with the concepts and principles indicated below, Kant appeals to:

two basic concepts of ‘time’ and of ‘space’,

an unspecified manifold of continuing sensory intake,

& his Thesis of Singular Cognitive Reference (above, §8).

JUDGMENTS

CATEGORIES

(A70/B95)

Quantity

Universal

Particular

Singular

(A80/B106)

Quantity

Unity

Plurality

Totality

Quality

Quality

Affirmative

Reality

Negative

Negation

Infinite

Limitation

SCHEMATISM of the Categories

(A145/B184–5)

PRINCIPLES of the UNDERSTANDING

(cf. A142–5/B182–4, A161/B200)

Schema of Magnitude:

= time-series (sequence)

{. spatial region; figure, size}

Axioms of Intuition

Extensive Magnitude

(A162/B202)

Any particular we can identify occupies some identifiable region of

space during some identifiable period of time.

Schema of Quality:

= time-content (duration)

{. spatial occupation; density}

Anticipations of Perception

Intensive Magnitude

(A166/B207)

Any perceptible quality has some degree of intensity.

Any bit of matter filling any space has some degree of active force or

causal power (cf. A172–5, 214/B214–6, 261).

Relation

Relation

Schema of Relation:

Analogies of Experience

Categorical

Inherence & Subsistence

= time order

Permanence of the Real in Time

Hypothetical

Cause & Effect

{. spatial order(s), array, locations}

Necessary Succession

Disjunctive

Community (causal reciprocity)

Reciprocal Causality

Modality

Modality

Problematic

Possibility – Impossibility

Assertoric

Existence – Non-Existence

Apodeictic

Necessity – Contingency

Schema of Modality:

= time-scope

{. spatial persistence}

Postulates of Empirical Thinking

Possibility:

Actuality:

Necessity:

(A215/B262)

Substance persists through changes of its states.

Changes of state of any 1 substance are (causally) regular.

Causal action of any spatio-temporal substance is causal interaction

between two (or more) of them.

(A218/B265–6)

Accord with conditions of temporal orderability {& spatial locatability}

Existence at some time {& location}

Existence at all times {in some location or other}

�References

Beck, Lewis White, 1978. ‘A Prussian Hume and a Scottish Kant’, in idem., Essays on Kant and Hume (New

Haven, Yale University Press), 111–129.

Brembs, Björn, 2011. ‘Towards a Scientifc Concept of Free Will as a Biological Trait: Spontaneous Actions and Decision-Making in Invertebrates’. Proceedings of the Royal Society: Biological Sciences 278:930–

939; DOI: 10.1098/rspb. 2010.2325.

Brook, Andrew, 1994. Kant and the Mind. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

———, 2016. ‘Kant’s View of the Mind and Consciousness of Self’. In: E.N. Zalta, ed., The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy; URL: <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2016/entries/kant-mind/> .

Corcoran, John, 1974. ‘Aristotle’s Natural Deduction System’. In: J. Corcoran, ed., Ancient Logic and its

Modern Interpretations (Dordrecht, Reidel), 85–132.

Edwards, B. Jeffrey, 2000. Substance, Force, and the Possibility of Knowledge. Berkeley, CA, University of California Press.

Evans, Gareth, 1975. ‘Identity and Predication’. Rpt. in: idem. (1985), Collected Papers (Oxford, Oxford University Press), 25–48.

Frege, Gottlob, 1879. Begriffschrift, eine der arithmetischen nachgebildete Formelsprache des reinen Denkens. Halle an

der Saale, Nebert.

———, 1967. ‘Begriffsschrift, a formula language, modeled upon that of arithmetic, for pure thought’, S.

Bauer-Mengelberg, tr. In: J. van Heijenoort, ed., From Frege to Gödel, A source book in mathematical logic,

1879–1931 (Cambridge, Mass., Harvard University Press), 5–82.

Guyer, Paul, 1987. Kant and the Claims of Knowledge. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

———, 1989. ‘Psychology and the Transcendental Deduction’. In: E. Förster, ed., Kant’s Transcendental

Deductions (Stanford, Stanford University Press), 47–68.

Hume, David., 1739–40. A Treatise of Human Nature. Critical ed., D.F. Norton & M.J. Norton (Oxford:

Oxford University Press: 2000).

———, 1748. An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding. Critical ed., T. Beauchamp (Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1999).

Kant, Immanuel, 1781. Critik der reinen Vernunft, 1st ed. Riga, Hartknoch; rpt. in: idem. (1998a), (2009).

———, 1787. Critik der reinen Vernunft, 2nd rev. ed. Riga, Hartknoch; rpt. in: idem. (1998a), (2009).

———, 1790. Kritik der Urteilskraft, GS 5:171–485; Critique of Judgment, cited as ‘KdU’.

———, 1902–. Kants Gesammelte Schriften. Könniglich Preussische, now Berlin-Brandenburgische Akademie der Wissenschaften. Berlin, Reimer, now deGruyter; cited as ‘GS’ by vol.:page numbers.

———, 1995–2016. P. Guyer & A. Wood, eds.-in-chief, The Cambridge Edition of the Works of Immanuel Kant in Translation, 16 vols. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

———, 1996. Critique of Pure Reason: Unified Edition. W. Pluhar, ed. & tr. Cambridge, Mass., Hackett Publishing Co.

———, 1998a. J. Timmermann, ed., Kritik der reinen Vernunft. Hamburg, Meiner.

———, 1998b. P. Guyer & A. Wood, trs., Critique of Pure Reason. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.