This essay represents a corrected version of the one that appears in the printed

volume entitled Indo-Muslim Cultures in Transition, eds. Alka Patel and Karen

miniatures

monuments

alam’s

111

Leonard. Leiden,to

Boston:

Brill. 2012. picturing

In the printedshah

publication,

somedelhi

of the figures

did not have the proper captions. This error, which was not the fault of the author or

editors, has been corrected here.

FROM MINIATURES TO MONUMENTS

PICTURING SHAH ALAM’S DELHI 17711806

Yuthika Sharma

Both my heart and Delhi are desolate

Yet I find comfort in this deserted city1

In January 1772 the reigning Mughal emperor Shah Alam II entered

Delhi with much pomp and splendor.2 In 1759 following his father’s

death, Shah Alam had ascended the masnad (throne) as the new

emperor but had stayed away from Delhi in a bid to garner support to

counter the monopoly of the minister Ghaziuddin who effectively

controlled the Mughal court under his father Alamgir II (r. 17541759). Yet, the desire to return to his ancestral home and reassert his

supremacy from the dar-al-khilafat, the traditional seat of empire at

Shahjahanabad, remained ever present. Following the Battle of Buxar

1764, Mughal geographical dominance had steadily diminished—its

major territories were now the hands of the British East India

Company.3 By the last quarter of the eighteenth century only the limits of the Mughal city of Shahjahanabad and the local environs of

Delhi constituted the bulk of Shah Alam’s political as well as geographical dominion, evoking the popular saying, “From Delhi to

Palam—the reign of Shah Alam.”

1

Mir Taqi Mir, Kulliyat, I, p. 496. As cited in Ishrat Haque, Glimpses of Mughal

Society and Culture (New Delhi: Concept Publication Company, 1992).

2

Shah Alam had fled Delhi following the occupation of the city by Ahmad Shah

Abdali in 1756-57 and moved around Patna and Varanasi. According to Jadunath

Sarkar Shah Alam II entered Delhi on 10 January 1772 but both Antoine Polier and

William Francklin suggest 25th December 1771 as the date of his return to Delhi. See

Jadunath Sarkar, Fall of the Mughal Empire (Calcutta: 1952), p. 555; A.L.H. Polier,

Shah Alam II and his court. A narrative of the transactions at the court of Delhy from

the year 1771 to the present time ... Ed. Pratul C. Gupta (1989); William Francklin,

History of the reign of Shah-Aulum (1798).

3

In 1764 after losing the battle of Buxar against the British East India Company

Shah Alam had signed a treaty handing over the diwani of Bihar, Bengal, and Orissa

to them, and moved to Allahabad where he was to remain for another seven years.

Later, Shah Alam conceded other territories in the Doab to Maratha chiefs in

exchange for a safe passage to Delhi.

�112

yuthika sharma

Against the backdrop of Shah Alam’s return to Delhi, this essay

looks at the pictorial modes of imagining Delhi and its environs from

the late eighteenth to the early nineteenth century, when the Mughal

house re-established itself in the city. It studies the enmeshed nature

of art, politics, and artistic agency manifested in the imagery of the

Qila i-Mualla (the Exalted Fort) at Delhi within Indo-European imagination, proposing that the pictorial representation of Shahjahanabad

and its environs was synonymous with the projection of later-Mughal

sovereignty. The visual stronghold of fort imagery, that referenced the

vocabulary of Mughal miniature painting as well as European topographical techniques of representation, offers a unique insight into the

constitutive role of these conventions in the development of the Delhi

school of painting under Shah Alam II and his successors. In this context, we look at the significance of works produced within a crosscultural artistic climate, under patrons such as Jean-Bapiste Gentil

(1726-1799) in Avadh and Antoine Louis Henri Polier (1741-1795) in

Delhi in the last quarter of the eighteenth century. Gentil’s commission of the Recueil des toutes sortes … (1774) and Polier’s own experience of the Mughal court at Delhi (ca. 1776) were, as we will see,

significant for building a topographical vocabulary for Shah Alam’s

imperial image through various modes of visualizing Shahjahanabad.

In this context, an early painting of the Red Fort dated to 1750 by the

Mughal court artist Nidha Mal (active 1735-75) is considered for its

repercussions on later cartographic drawings commissioned by Gentil

and Polier. Nidha Mal’s own migration from Delhi to Avadh is a significant subtext for this analysis, in the wake of successive attacks on

Delhi by the Afghan ruler Ahmad Shah Abdali (reigned 1747-1773),

and other rival political groups. As Delhi artists found reemployment

in the provincial courts, they were also absorbed into the emerging

information network of European surveys of Indian territories. The

agency of these local artists in this process of topographical translation was paramount, as they were able to re-imagine Mughal kingship

largely in terms of its architectural and geographical symbolism.

Mapping Delhi, Depicting Shahjahanabad

Delhi continued to enjoy the unique position of being an intellectual,

spiritual, and cultural center of the Mughal Empire and this was

reflected in its prominence as a regional stronghold as well as urban

�miniatures to monuments picturing shah alam’s delhi

113

center under Mughal rule.4 Eighteenth-century topographical and statistical records reiterate the delineation of Delhi both as a suba (province) and as a sarkar (division) following the initial guidelines laid out

in the A�in i-Akbari compiled by Abu’l Fazl (1551-1602) at the end of

the sixteenth century.5 As a suba, the Delhi province enjoyed revenues

from numerous divisions and sub-divisions while Delhi sarkar contained the vast historical footprint of older fortifications and cities

ruled by numerous powers for over a millennium.6 The sarkar

accounted for three mahals (sub-divisions)—the Haveli-i Qadimi (old

buildings), the Haveli-i Jadid (new buildings), and the capital city of

Dihli, referring to the Mughal city of Shahjahanabad built under Shah

Jahan (reigned 1628-1658).7 Later topographical accounts such as the

Khulasat-ut-Tawarikh by Sujan Rai Bhandari (1695) and the Chahar

Gulshan by Rai Chatirman (ca. 1720/1759) celebrate the primacy of

Delhi as an important socio-cultural locus of the Mughal Empire.8 It is

noteworthy that the Khulasat, also translated in 1728 for the Mughal

emperor Muhammad Shah (reigned 1719-1748) at Delhi, takes a

somewhat unconventional recourse into verse when describing

Shahajahanabad, assuming the format of a literary urban ethnography. This intersection between idealized and observed forms of city

description was common to the large body of Indo-Persian ethnographies of Delhi that utilized the literary tropes of shahr ashub and shahr

4

Delhi was a site of ritual significance and imperial hunts prior to the construction of Shahjahanabad. Ebba Koch, “Shah Jahan’s visits to Delhi prior to 1648”: New

evidence of ritual movement in urban Mughal India.” Mughal Architecture: Pomp

and Ceremonies, Environmental Design 1-2 (1991): 18-29.

5

The manual served as an important model for later terrestrial and revenue

records created under Aurangzeb (1658-1707) and the later Mughals. For example,

see the initial comparison offered by Jadunath Sarkar, The India of Aurangzib

(Topography, Statistics, and Roads) compared with the India of Akbar. With extracts

from the Khulasatu-t-Tawarikh and the Chahar Gulshan (Calcutta, 1901).

6

For an analysis of Delhi’s greater economic potential compared with Agra see,

K.K. Trivedi, “The Emergence of Agra as a Capital and a City: A Note on Its Spatial

and Historical Background during the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries” Journal

of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, 37, No. 2 (1994) 147-170.

7

Along with these mahals, the Western and Eastern tracts of the Jamuna were

also accounted for in early administrative tabulations for the suba. After 1648, following the construction of Shahjahanabad the nomenclature for Delhi shifted to

‘Shahjahanabad’ or ‘Jahanabad’, and by the eighteenth century, Shahjahanabad

seems to have been used to refer to the entire suba. Irfan Habib, An atlas of the

Mughal Empire (1982).

8

Khulasat-ut-Tawarikh, ed. Zafar Hasan (Delhi, 1918).

�114

yuthika sharma

ashob to comment on the vitality of the city.9 A detailed exploration of

the intersecting notions of space and territoriality in the literary and

visual realms lies outside the immediate scope of this paper. However,

it is worth noting that such literary forms that projected ideas of an

inscribed space also underwent a simultaneous process of routinization and serialization in part due to the influence of maps and census

taking practices in this period.10 Mid-century pictorial mappings of

Delhi embody the conceptual logic of statistical and literary mappings

of the city continuing to represent Delhi as the locus of imperial power

in the face of political upheaval.

Two surviving maps depicting Shahjahanabad allow us to understand the city as it would have been locally imagined, serving as

important visual documents conveying topographical information.

These maps coincide with the completion of Chahar Gulshan by Rai

Chaturman in 1759 in Delhi for the puppet emperor Shah Jahan III

(reigned 1759).11 Although much of its statistical content reflects the

conditions of the Mughal State ca.1720 the text, along with other

extant topographical manuals, would have likely provided the source

material for these two maps.12 The first of these is a set of two scrolls

approximately 0.2 by 20 meters and 0.2 by 12 meters long showing

route maps from Shahjahanabad to Kandahar datable to between

1770 and 1780 (See Color Plate 6.1). The scroll, which is compositionally centered along the central stretch of a road, traverses the main

9

For an overview of Indo-Persian urban ethnographies, see Sunil Sharma, “City

of Beauties in the Indo-Persian Poetic Landscape,” Comparative Studies of South

Asia, Africa and the Middle East 24, no. 2 (2004): 73-81.

10

Henry Scholberg, The District Gazetteers of British India: a Bibliography. (Zug,

Switzerland: Inter Documentation Co., 1970); Emmett, Robert C. “The Gazetteers of

India.” M.A. Thesis, University of Chicago, 1976. Indo-Persian urban ethnographies

also formed the basis of topographical gazetteers such as Asar- us-Sanadid produced

in 19th century Delhi. See, Sunil Sharma, “Urban Ethnography in Indo-Persian

Poetic and Historical Texts”, Manuscript, 2005; See also Carla Petievich, “Poetry of

the Declining Mughals: The Shahr Ashob,” Journal of South Asian Literature, 25,

vol.1 (1990): 99-110.

11

Sarkar’s translation of the inscription may be slightly incorrect as he names the

emperor as Shah Jahan II, but his transliteration points out that the Chahar Gulshan

was prepared as dynastic history for the emperor “who increased the splendor of the

throne in the year 1173 ah (ad 1759) with the help of the Wazir of the Empire

Ghazi-ud-din Khan alias Shahab ud-din Khan at the time of the second invasion of

Ahmed Shah Abdali.” Sarkar India of Aurangzib, xv-xvi.

12

For instance, the Khulasat would have likely formed a basis for the compilation

of base material for the Chahar Gulshan. Both texts, as Sarkar points out, were in

large part based on the A�in-i Akbari. Ibid.

�miniatures to monuments picturing shah alam’s delhi

115

outposts of cities such as Qandahar, Kabul, Lahore, and Shahjahanabad.13 The final destination of Shahjahanabad is depicted through its

main elements—the main gateways leading into the fortified city,

the nahr-i-bahisht and sarais, and a minimalist planimetric view of

the Red Fort. This convention for depicting the fort highlights its

visual emphasis in red and blue identifying the main palace structures

along the eastern length of the fort, its adjacent fortifications, the Jami

Mosque, the Faiz canal, Chandni Chowk, and the various gateways

that form the outposts of the fortified city.14 Residences are shown as

square plans comprising of rooms organized around a central courtyard while important shrines are marked by views of tombstones and

mosques are identified by their plans with the major minarets shown

in elevation. Landscape features, too, are fairly standardized with the

depiction of various types of gardens as either walled or those lying

along the main road or a river.15 The route largely conforms to the

main topographical features and roadways described in the Chahar

Gulshan, however the map is a detailed rendering of the religious, cultural, and urban centers along the route.16

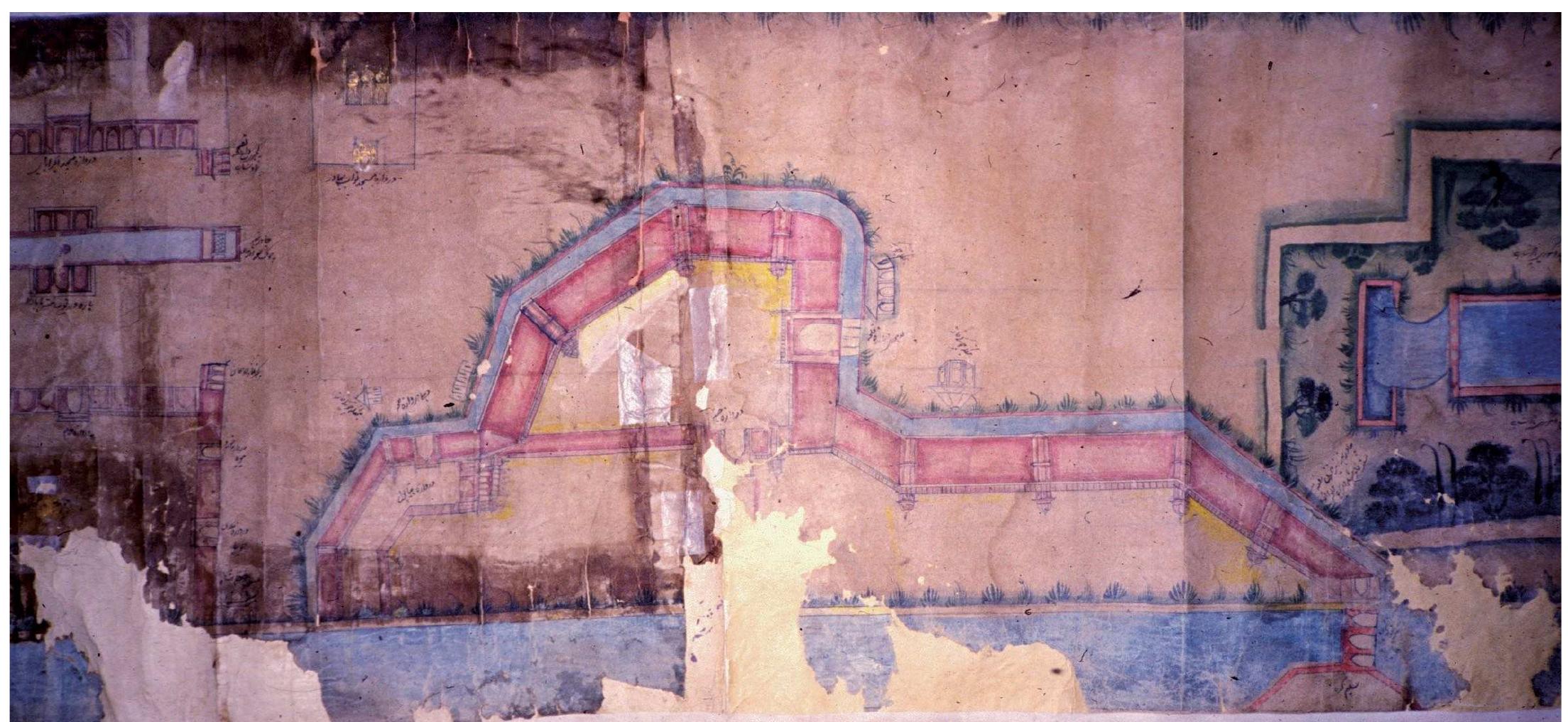

A second twelve-meter long topographical map from ca.1760, tracing the path of the monumental water-works of the nahr-i-bahisht

canal undertaken by Shah Jahan’s engineer Ali Mardan Khan, follows

the logic of the earlier route map but with greater naturalistic detail.17

(CP 6.2) The nahr-i-bahisht (Paradise Canal), as it was officially

known, was laid out at the time of the building of Shahjahanabad

in 1630 and only functioned intermittently in the mid eighteenth

century.18 The map’s distinctive topographic palette details distances,

measurements, and techniques of water harnessing along the length

of canal charting its formal transition from a sinuous watercourse to a

13

The inscription notes that the map was made by Maulvi Qulam Qadir who was

in Kandahar with Mountstuart Elphintsone in 1814. However, Susan Gole has

shown on the basis of internal evidence that the maps can be dated to the period

after the 1760s.

14

Susan Gole, Indian maps and plans: from the earliest times to the advent of

European surveys (Manohar: Delhi, 1989), 94-103.

15

See Philippa Vaughan, “The Mughal Garden At Hasan Abdal, a Unique Surviving Example of a ‘Manzil’ Bagh” South Asia Research, vol. 15(Sep 1995): 241- 265.

16

See “Roads” in Chahar Gulshan, Sarkar, India of Aurangzib, 174-175.

17

Ali Mardan Khan was largely responsible for extending the Canal from Hansi

and Hisar to the northwestern suburbs of the city that spanned a distance of seventyeight miles. Susan Gole, Indian maps and plans, 104-109.

18

Stephen Blake, Shahjahanabad, The sovereign city in Mughal India 1639-1739.

(Cambridge, 1993), 64.

�116

yuthika sharma

rectilinear waterway. The section of the map dealing with urban Delhi

follows the visual convention of a planimetric layout with buildings in

elevation. More importantly, even as the map conveys the idea of the

water-bearing canal as a technological achievement, it evokes its beneficence as a canal of Paradise that imparts heavenly fervor to Delhi’s

landscape. This beneficence is sanctioned by spiritual means too, for

we find that the shrine of the Sufi saint Bu ‘Ali Qalandar, illuminated

in gold, figures conspicuously in the very first section of the canal’s

inauguration in the village of Benawas (CP 6.3).19

Mughal mapping and survey practices also provided crucial base

material for the development of European cartography in the Indian

subcontinent in the eighteenth century.20 In addition to providing the

core information for geographic and cadastral maps prepared by missionaries and surveyors, the preparation of such surveys was highly

dependant on local informants, surveyors, and agents whose ability to

transcribe information, visually or in written form, was indispensable

to this process.21 The demand for “accurate” information by missions

of the Dutch, French, and British East India Companies had led to a

number of disparate efforts to produce cartographic information on

various regions of India since the beginning of the eighteenth

-century.22 Simultaneously, early modern European techniques of

19

The view of the shrine is not architecturally accurate nor does Bu ‘Ali’s shrine

lie in such close proximity to the canal. Nineteenth-century depictions show Bu

‘Ali’s shrine within an enclosed courtyard. Ibid.

20

For instance Jesuit missionaries such as Joseph Teiffenthaler (1710-1785) were

engaged in recording these prevailing systems of land survey and also involved in

producing topographical images and maps of regions in India. See La Géographie de

l’Indoustan, écrite en Latin, dans le pays même, par le Pere [sic] Joseph Tieffenthaler

Jésuite & Missionaire apostolique dans l’Inde. Vol. I in Jean Bernoulli, ed. Description

historique et géographique de l’Inde, 3 volumes (Berlin: Pierre Bordeaux, 1786-8). For

an overview of modern mapping in the subcontinent see Kapil Raj, Relocating Modern Science: Circulation and the Construction of Knowledge in South Asia and Europe,

1650-1900 (Palgrave Macmillan, 2007), 60-82.

21

Raj Relocating Modern Science; Raj, “Circulation and the emergence of modern

mapping, Great Britain and early colonial India, 1764-1820” in Subrahmanyam,

et al., eds. Society and Circulation: Mobile People and Itinerant Cultures in South Asia

1750-1950 (Permanent Black, 2003), 23-54.

22

Thus, missionaries and antiquarians such as Teiffenthaler and AntequilDuperron (1731-1805) relied heavily upon local scribes, guides, engineers, draftsmen

and artists for their topographical surveys. Teiffenthaler, La Géographie de

l’Indoustan; Des Recherches historiques and chronologiques sur l’Inde, & la Description du Cours du ange & du Gagra, avec une trés grande Carte, par M. Antequil Du

Perron de l’Acad. Des Insc, & B.L. & Interpréte du Roi pour les langues orientales, à

Paris’ in Bernoulli, op. cit. Vols. I and II.

�miniatures to monuments picturing shah alam’s delhi

117

mapping also filtered into mainstream Mughal artistic culture and

featured quite prominently within visual practices of the Mughal

imperial atelier. For instance, the visual projection of the terrestrial

globe in paintings for the Mughal emperors Jahangir (reigned 16051627) and later Shah Jahan was a means to reconstruct and even alter

the globe’s spatial logic in the service of fashioning the imperial Self.23

The absorption of European spatial practices into Mughal painting

at Delhi can be seen in the later work of the Mughal court artist Nidha

Mal, who was active from the second quarter of the eighteenth century. A plan of the Red Fort signed “Amal-i Nidha Mal” and inscribed

with a date of 1750, rendered in the traditional technique of gouache

and watercolor, may well be the earliest example of a cartographic

depiction of the Red Fort and its environs at Delhi by a Mughal artist

incorporating elements of European conventions (CP 6.4). The fort

plan contains multiple labels in Persian identifying key mosques, settlements, and gardens (e.g. Angur-i Bagh) outside the fort, the gateways and bastions (e.g. Dilli Darwaza and Hathia Pol), and the main

buildings and apartments of the Mughal palace within the Fort complex. Since the map is extensively repaired with gauze it is very difficult to ascertain the quality of the paper used to prepare this work.

Nidha Mal’s signature provides a guide for orienting the plan such

that the map is oriented along its East-West axis, thus giving prominence to the eastern façade of the fort that contains the royal buildings

such as the Diwan-i Am, Diwan-i Khas and the Shah Burj.

The Red Fort is shown in a square planar format with its fortifications, gateways, buildings, and vegetation in elevation. But most

noticeably the center of the fort is left empty as if to emphasize its

focus on the fortification and its immediate environs. This feature

anticipates the conventions for fort renderings in the two route maps

discussed earlier. More significantly, it recalls elements of European

engineering drawings, especially the format of an isometric perspective or perspective cavalière—that privileged a two dimensional view

23

The terrestrial globe often functioned as a cartographic artifact within early

modern Mughal painting—as an “…imperial prerogative par excellence, and joins

the ranks of such exclusive signifiers of imperial sovereignty such as the crown, the

plume or turban ornament, the precious gem, the falcon, and the ceremonial robe of

honor” situated on the “‘… the Emperor’s person as an embodiment of Empire,’ and

in this case, … the world itself.” Sumathi Ramaswamy, “Conceit of the Globe in

Mughal Visual Practice.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 49, no. 4 (2007):

751-82. John F. Richards, ed. Kingship and Authority in South Asia, (1998), 128.

�118

yuthika sharma

of the building. Military perspectives such as these were used extensively to illustrate the design of fortifications in seventeenth and eighteenth-century Europe, and can be seen in the seminal treatises by the

Frenchman Monsieur de Vauban and the Dutch engineer Menno

Baron van Coehoorn.24 The main emphasis in these illustrations was

on the frontiers of a fort that brought into prominence its bastions

and outer-works whose designs were being constantly worked upon

by fort engineers.25 The artistic convention of the military perspective

dispensed with any details of the interior of the fort, which were considered extraneous to the purpose of delineation. Thus, the blank center of the Fort complex reinforced the idea of the fort as a defensible

establishment. The sole choice of populating this landscape with

horses in stables, cannons, and soldiers in the inner forecourt of the

Delhi Gate, and the proliferation of labels identifying the outer bastions and environs of the fort further enhances the military character

of this painting.

Complementing this pragmatic rendering of the Red Fort is the

elevated view of the emperor’s palace delineated through the use of

red canopies commonly used to demarcate imperial presence in

Mughal painting. The backdrop of the eastern face of the palace

complex at the Red Fort became increasingly popular in paintings

from Muhammad Shah’s reign and is carried forward here in Nidha

Mal’s map of the Red Fort.26 Nidha Mal’s penchant for detailing

24

For instance see William Allingham’s translation of the late 17th century treatise by de Vauban titled The new method of fortification, as practised by Monsieur de

Vauban engineer-general of France. Together with a new treatise of geometry. The

fourth edition, carefully revised & corrected by the original. ... By W. Allingham, ...

(London, 1722). Also see, The new method of fortification. Translated from the original Dutch, of the late famous engineer, Minno Baron of Koehoorn, ... By Tho. Savery

gent. (London, 1705). Also see, Prost, Philippe, Les fortresses de l’Empire. Fortifications, villes de guerre et arsenaux napoléoniens, (Paris: Editions du Moniteur, 1991).

Also see, Alexis Rinckenbach, Les Villes Fleurs. Aventures et catrogrpahie des Francais aux Indes aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles. Petit Journal de l’Exposition, Port-Louis

(France): Musée de la Compagnie des Indes, (1998).

25

Horst. Remarks on a new system of fortification. Proposed by M. le Comte de

Saxe, in his memoirs on the art of war. Trans. Charles Theodore D’ Asti (Edinburgh,

1787). By the late eighteenth century, there were significant revisions in the designs

of fortifications advanced by Vauban and Coehoorn. The author puts forward M. le

Comte de Saxe’s revisions on the earlier treatises putting greater emphasis on the

development of the outer-works of fortifications, a greater scope for technical

improvement and therefore of greater defensibility.

26

This element is also seen in the work of Bhupal Singh and Hunhar. For an

overview of paintings produced in Muhammad Shah’s atelier, see Terence McInerney. “Mughal Painting during the Reign of Muhammad Shah,” in After the Great

�miniatures to monuments picturing shah alam’s delhi

119

architectural and landscape elements can be observed in his largescaled paintings for Muhammad Shah (B/W 6.5). In the first brush

drawing painted ca. 1725 Muhammad Shah and his courtiers are seen

in the midst of a verdant garden landscape rendered with botanical

clarity. The foreground and background are merged into the common

pictorial space organized along the quadripartite sections of a fourpart garden. In the second painting from the same period, the figures

of the emperor and his courtiers are positioned on a garden terrace set

against the brightly canopied structure of the Hall of Special Audience.

In keeping with the overall formality of this evening conference,

Nidha Mal has depicted the planting constrained to the two sides of

the painting, leaving the garden space fairly plain and drawing the

focus to the central figures.

In both paintings, the palace buildings with their distinctive canopies sit above eye-level and are placed above the emperor’s physical

position. The placement of the figures is more in keeping with the spatial hierarchy of a geometric picture plane rather than the conventions

of Mughal imperial court paintings, where the emperor physical

placement was usually higher than his subordinates. Nidha Mal’s

court paintings were very much in accordance with the ongoing

experimentation of Mughal artists with European volume and pictorial space while trying to balance the hierarchy of traditional ceremonial scenes. The rendering of the landscape, observed from the

eye-level of the onlooker rather than a higher viewpoint in paintings

for Muhammad Shah, forms a significant precedent for the experiments with light, spatial depth, and volume that artists in the provincial courts of Murshidabad, Patna, and Avadh began to undertake,

setting their subjects within a geometrically devised setting based on

European perspective.27 In the Fort map of 1750 painted after the

death of Muhammad Shah, Nidha Mal retains his characteristic

Mughals: Painting in Delhi and the Regional Courts in the 18th and 19th Centuries,

ed. Barbara Schmitz, MARG 53, no. 4 (2002), 12-33.

27

See Jeremiah P. Losty. “Towards a New Naturalism: Portraiture in Murshidabad and Avadh 1750-80.” MARG 53, no. 4 (2002): 34-55. Molly Aitken offers an

alternative perspective to viewing the ‘concerns of naturalism’ articulated by

J.P. Losty and Linda Leach, arguing in favor of such compositional ‘failures,’ which

attempted to balance Mughal and European spatial hieratics. Molly Emma Aitken,

“Parataxis and the Practice of Reuse: From Mughal Margins to Mir Kalan Khan”

Archives of Asian Art 59 (2009): 81-103. See also Linda Leach, Mughal and Other

Rajput Paintings from the Chester Beatty Library, vol. II (London: Scorpion Cavendish, 1995), 685.

�120

yuthika sharma

treatment of vegetation, cluster planting and palace buildings while

working with the planar vocabulary of a cartographic map.Furthermore, he employs visual correctives to guide the viewer’s eye to the

imperial buildings in the palace by aligning the Shah Burj in the Khas

Mahal with the main entrance, the Lahore Gate.

A Provincial View to Shah Alam II’s Shahjahanabad

Nidha Mal’s migration to Avadh after 1750 offers an important context for situating the re-employment of miniature painters as topographical artists in the last quarter of the eighteenth century. His move

to Avadh was recorded in a letter dated 18th September 1772 by a

clerk named Sankaraja Satyadeva to Nana Phadnavis, the Maratha

Peshwa Madho Rao Narayan’s minister at Delhi. Satyadeva, who was

ambassador to Phadnavis in Delhi stated that the paintings were hard

to obtain since the Hindu nobility had left Delhi and fine artists were

starving to death and mentions Nidha Mal’s migration to Lucknow in

this context.28 Avadh played host to the Mughal emperor Shah Alam

II for a number of years, and the emperor’s presence spurred a number of topographical commissions that provide crucial art historical

context for Shah Alam’s movements prior to his return to Delhi.

Moreover, these commissions reflect how diverse painting genres,

especially those lying outside the purview of court painting in the

provinces, engaged directly with Mughal history and imperial narrative towards the end of the eighteenth century. The province’s

European residents such as Jean-Baptiste Gentil, the official agent of

the French King Louis XVI to the court of Nawab Shuja ud-Daula

(1732-1775), and Antoine Louis Henri Polier, the Nawab’s official

engineer and architect, were individuals whose involvement with the

itinerant Mughal court under Shah Alam warrants greater examination in this respect.29

28

Satyadeva also mentions Nidha Mal’s subsequent death there. Itihasa Sangraha

Aitihasik Tipane, (1981), 1, no. 11 (September, 1908). First published in Falk and

Archer, Indian Miniatures of the India Office Library, 122. The ambassador also

reported that both of Nidha Mal’s sons were reported to be working in Lucknow but

that one of them was said to be useless and the other mediocre. See, Patricia Bahree

Baryiski “Paining in Avadh in the 18th Century”, Islam and Indian Regions, eds. A.L.

Dallapiccola and S.Z.-A. Lallemant (Stuttgart 1993), vol. 1, 351-66, vol. 2, plates.

31-40.

29

For a brief overview of Gentil’s career see Archer Company Paintings, (1992),

117-118; Jean-Marie Lafont, Chitra: Cities and monuments of eighteenth-century

India from French archives (Oxford, 2001).

�miniatures to monuments picturing shah alam’s delhi

121

Gentil is perhaps best known for his endeavor to visualize topographical information about the subcontinent from local and European manuals into a geographical atlas titled, Empire Mogol divisé en

21 soubahs ou Gouvernements tiré de differens ecrivains du païs a

Faisabad MDCCLXX (1771).30 The forty-two folios of the atlas are a

remarkable exercise in topographical representation following the

logic of older texts such as the A�in i-Akbari (1595) but blending them

with the existing state of European information on the subcontinent

in a comprehensive visual format.31 The atlas is divided into folios representing each suba, then illustrated in cadastral detail showing the

routes and connections between various towns, the cities within, and

the geographical features of the region such as mountain ranges, forests, rivers, and at times lakes and smaller water bodies.32 The remarkable addition to each map are genre and mythological scenes in

miniature that appear to function as ethnographic and cultural

vignettes, which are meant to provide a visual supplement to the cartographic views of each suba. In addition to devising a visual vocabulary for annotating architecture and landscape that provided each

suba with its distinctive characteristic, the use of delicate colors, grays,

pink, mauve, pale yellow and green, in the atlas represents the “…first

adjustments to European tastes and interests…(these) subjects which

were later to become the stock-in-trade of ‘Company’ painters were

already present in miniature form.”33

In the first folio illustrating the suba of Shahjahanabad (Chadjeanabad) Gentil provides a compelling view into the current state of

Mughal rule (B/W 6.6).34 The map of Shahjahanabad contains very

30

Susan Gole, Maps of Mughal India (1988), Introduction. Other examples of

Mughal sources that compile geographical and administrative information include

Yusuf Mirak’s Mazhar-i Shahjahani (1634) for Sind, Nainsi’s Vigat (c. 1664) for

Marwar, Ali Muhammad Khan’s Mir' at i-Ahmadi supplement (1761) for Gujarat.

Irfan Habib, Atlas of the Mughal Empire (1982).

31

It has been suggested that Gentil’s atlas largely dew upon the coastline of Jean

Baptiste Bourguignon d’Anville Carte de l’Inde made in 1752 and published in 1771.

Gole, Maps of Mughal India, Introduction.

32

Gentil’s survey of the caves, which was used by Antequil Duperron, was one of

many essential surveys to be compiled. Similarly, the view of the famous fort at the

suba of Allahabad is likely a copy of the fort provided to Gentil by Teiffenthaler.

Gole, Maps of Mughal India, Introduction; Lafont, Chitra, 9.

33

Jean-Marie Lafont has used the term ‘farenghi art’ to define this early phase of

European patronage. Lafont, Chitra, 11.

34

This practice is noticeably different from the nomenclature of the Ain, where

the sarkar (capital) of Delhi is based within the suba of Sirhind. See Abu�l Fazl, A�in-i

�122

yuthika sharma

few figures unlike the maps of other subas, where genre and mythological scenes set the context for the cartographic mappings. As if to

emphasize the Mughal emperor Shah Alam’s absence from the city,

the accompanying miniatures on the map show royal and courtly

accoutrements such as standards, parasols, howdahs, a tent, a reproduction of the peacock throne of Shah Jahan, and musical instruments—all objects constituting royal paraphernalia. However, in the

absence of the emperor’s figure they seem somewhat displaced, static,

and noticeably lacking in vigor, especially as they occur in the first

folio of the atlas. In contrast, the description of the province of Avadh

shows a vignette of Nawab Shuja-ud-Daula and Gentil on elephantback engaged in a lion hunt flanked by an army of soldiers. Using the

quintessential idea of the hunt as a means of projecting royal authority, the atlas situates Avadh as the new outpost of Mughal culture.35

The choice of illustrations showing fakirs, mythological scenes, flora,

and fauna reflects Gentil’s own interests as a manuscript collector and

these vignettes are distinctly related to the paintings he commissioned

during his stay at Avadh.36

In a second compendium commissioned by Gentil a few years later

following Shah Alam’s return to Delhi, the structure of Mughal imperial authority is consciously resurrected. In the album Recueil de toutes

sortes de Dessins sur les Usages et coutumes des Peuples de l'indoustan

ou Empire Mogol d’après plusiers peintres Indiens, Nevasilal, Mounsingue & c. au service du Nabab visir Soudjaatdaula Gouverneur general

des provinces d’ Eléabad et d’ Avad. Lequel recueil a été fait par les soins

du Sr Gentil, Colonel d’Infanterie; en 1774 à Faisabad (1774), Gentil

emphasizes Shah Alam’s recently restored status at Delhi in a more

direct fashion, dedicating the first section of the album to the activities

of the Mughal emperor and his court. In the very first illustrated folio,

the courtly accessories that appeared in the atlas to depict Shah Alam’s

absentia from Delhi were now given a proper context—forming an

array of the material accoutrements of the Mughal court shown in

Akbari, trans. H. Blochman (1927, reprint 1965); Irfan Habib, Atlas of the Mughal

Empire,10.

35

On the imperial significance of the Mughal Hunt see, Ebba Koch, Dara Shikoh

Shooting Nilgais. Hunt and Landscape in Mughal Painting (Occasional Papers, Freer

Gallery of Art, 1998).

36

In addition to mythological scenes from the Mahabharata and the Ramayana,

pictures of yogis, festivals, acrobats, birds and animals seen in this page are also reminiscent of Gentil’s own interests. See selections from Gentil’s collection in A la cour

de Grand Moghol (Paris: Bibliothèque Nationale, 1986).

�miniatures to monuments picturing shah alam’s delhi

123

session. Shah Alam is seated on a takht (throne) in the topmost row

surrounded by his main courtiers, standards, thrones, and musical

instruments. The second folio is one of the only known pictures that

celebrate Shah Alam’s accession to the throne of Delhi, referring to

the twelfth year of his reign, which was also when new coinage was

struck in celebration of this milestone.

In the Recueil, Gentil’s biography of Shah Alam is interspersed

along with the illustrated account of his own life in Shuja-ud-Daula’s

court. In 1772 Gentil had married into a family with ancestral connections with the Mughal domestic sphere. Gentil married Therese Velho,

the daughter of Lucia Mendece, the great-niece of one Juliana, who

had been entrusted with the education of the Mughal emperor

Alamgir I’s son Muhammad Muazzam, Shah Alam Bahadur Shah I

(reigned 1707-1712).37 This historical consciousness is palpable in

Gentil’s attempt to interweave the historical narrative of the Mughal

court with his own experience at Avadh. Gentil’s use of personal anecdotes detailing his interaction with the current Mughal emperor

exemplifies this. After recounting the instance of Shah Alam II’s asylum with Shuja ud-Daula, Gentil mentions the emperor’s eagerness to

meet him and also employ him, and his consequent unwillingness to

join the emperor’s service.38 (B/W 6.7) Later in the context of Shuja

ud-Daula’s efforts to annex the vacated fortress of Allahabad, Gentil

mentions Shah Alam’s departure for Delhi, which seems to offer a

turning point in the narrative.39 The Recueil is a rare instance of the

visualization of Mughal sovereignty in the late eighteenth century,

when Mughal power was politically at its weakest. It is in the Recueil

that we first recognize an attempt to visually narrate the history of

Shah Alam’s rule. The number of folios dedicated to Shah Alam’s

court and leisure activities in the Recueil point to the importance of

the emperor’s return to the Mughal capital, the sole act that reinstated

him as the Mughal sovereign in the eyes of the general public. This

event for Gentil is no doubt also the definitive moment marking Shah

Alam’s reign—he annotates a scene showing Shah Alam II hunting in

37

Juliana’s name was made out as a hereditary title passed down through six

generations and Therese was the last ‘Juliana’ in this lineage. Shah Alam I was known

to have given Juliana Dara Shikoh’s palace in Delhi, which was in her family’s possession and taken by Safdar Jang, Shuja ud-Daula’s father and then wazir of Delhi.

Jean-Marie Lafont, Chitra, 11.

38

Recueil, f.15 (a)-f.16 (a).

39

Recueil, f.20 (a).

�124

yuthika sharma

the garden at Faizabad as “Chasse dans la parc du Faisabad faite par

l’Empereur Cha alem aujourdhui regnant/ A hunt in the park at

Faizabad by the reigning Emperor Shah Alam.” (CP 6.8)

Topographical experiments in the Receuil prepared in 1774 draw

upon some of the earlier ideas of the atlas. Ranging from vignettes of

military and diplomatic encounters, leisure activities such as the hunt,

court activities, and religious, and ethnographic scenes, the Receuil

functions as a historical document while being oriented from the particular perspective of Gentil’s interests. Gentil’s dedication in the

Recueil naming the artists Nevasi Lal and Mohan Singh highlights the

intersecting realms of court patronage in Avadh under Nawab Shuja

ud-Daula and an emergent class of European patrons.40 Nevasi Lal

emerges as a figure of multiple talents—as a copyist in miniature of

oil-portraits of Shuja ud-Daula painted by the western artist Tilly

Kettle in Faizabad ca. 1771, as well as a topographer who illustrated

the Receuil and other albums for Gentil.41 Mohan Singh, who is

extolled by Gentil for his work on the Receuil, was the son of

Govardhan II who had worked at the court of Mohammad Shah at

Delhi.42 Such multiple correspondences between the miniatures in the

atlas and the Recueil point to the existence of stock sets of popular

images that were available to artists within a commercial set-up that

allowed for their easy replication and use in various contexts. For

example the drawings in Gentil’s atlas can be attributed to a number

of artists such as Sital Das, Gobind Singh and Ghulam Reza who, like

Mohan Singh, worked for the assistant to the British Resident at

Lucknow Richard Johnson between 1780-82. Sital Das’s paintings of

40

For an overview of the patronage base in Avadh during the reign of Shuja udDaula, see Natasha Eaton, “Critical cosmopolitanism” gifting and collecting art at

Lucknow, 1775-97 in Art and the British empire, ed. Barringer et al., (Manchester,

2007), 189-204.

41

Nevasi Lal’s expertise as a copyist of oil portraits is recounted in Gentil’s memoirs where he mentions how Shuja ud-Daulah was particularly taken by Nevasi Lal’s

copy of an oil portrait by Kettle, and wanted to keep it for him. Gentil’s playful

objection resulted in the Nawab giving him Kettle’s portrait in exchange of the copy.

Recounted in Mémoires sur l’indoustan ou Empire Mogol. Cited in Mildred Archer,

Company Paintings, 118. See also Archer, ‘Tilly Kettle and the Court of Oude (17721778)’ Apollo, (Feb 1972): 96-106.

42

For a discussion of Govardhan II, see McInerney, “Reign of Muhammad

Shah,” 12-33. In a folio from the ‘Iyar i-Danish from the Johnson collection, Mohan

Singh has signed the work “amal-i mohan singh valad-i govardhan”—the work of

Mohan Singh, son of Govardhan. See British Library, Add.Or J.54, 26. For Ragamala

paintings by Govardhan and other scenes see Falk and Archer, Indian Miniatures

(1981), 106, nos. 168-174.

�miniatures to monuments picturing shah alam’s delhi

125

Vedic sacrifices (Album 5) for Johnson are those that appear in the

map of Khandesh in Gentil’s atlas.43

From Avadh to Delhi: Polier and the Mughal Court of Shah Alam

As we have seen Shah Alam’s return to Delhi in 1772 offered much

artistic impetus to the visualization of the emperor’s reinstatement in

the historic seat of empire at Delhi. Where large-scale migration of

artists from Delhi to Avadh had become commonplace a few decades

earlier, the emperor’s move to Delhi attracted Avadh officials, who

brought artists along with them for a small but significant period of

time. The tenure of Antoine Louis Henri Polier, the engineer and

architect to the Avadh Nawab, is one such important instance that

raises a number of possibilities for reassessing the artistic climate of

Delhi in this period and the role of topographical imagery within it.

By 1767, Polier had gained a reputation as a fort engineer because

of his designs, improvements, and field advice for Fort William at

Calcutta and later for the fort of Chunar near Benaras. As a military

engineer Polier was involved in the commissioning of measured drawings and preliminary cartographic works, which ultimately became

part of such topographical surveys.44 For instance, Polier’s appointment as the Chief surveyor of Avadh in April 1773 was expected to

yield a detailed map of the area to be used for the Surveyor-General

James Rennell’s initial survey reports on Avadh and the northern territories.45 However, Polier’s involvement with a rival Mughal cause

involving the siege of Agra led to his discharge from Avadh and eventual departure to Shah Alam’s court at Delhi. After being chastised for

overstepping his role as a surveyor by imparting military intelligence

and strategic advice to Najaf Khan, Shah Alam’s Mir Bakshi

43

Archer IOL Report (1978), as cited by Gole, Maps of Mughal India, Introduc-

tion.

44

For example, Gentil was a close contact of both Teiffenthaler and Duperron,

and shared visual information on fortifications and towns with them.

45

After 1776, Rennell having completed his map of Bihar and Bengal extended it

up to Delhi finally publishing his map of India in 1782. Rosie Llewellyn-Jones, A very

ingenious man: Claude Martin in early colonial India (Oxford: Delhi, 1992), 55-56.

Llewellyn-Jones points out that though Polier did send the reports he had promised

Hastings and Rennell, there was ‘great room for improvement’ which was more a

‘skeleton’ rather than a finished map of Avadh. Also see, Matthew H. Edney, Mapping an Empire (Chicago, 1990).

�126

yuthika sharma

(Commander in Chief), Polier finally resigned in October 1775 and

accepted a short-term employment with Shah Alam II at Delhi.46

This phase of Polier’s career in Delhi remains to be explored for the

sum of possibilities that it offers. In February 1776, Polier wrote to the

Emperor requesting an audience:

I have been honored with a special shuqqa from you which I received

together with the letter of Nawab Majd-ud-Daula. It has been my long

standing desire to be in your service and to do something to set right

the management of the Empire and reinforce the law and order. I have

given up the Company job and have arrived in Akbarabad with the

intention to come to the court and meet you. I hope that I will soon

be honored by meeting you and by being ordered to be in your service

forever.

�Arzdasht to the Emperor, 7 Muharram, Tuesday, Akbarabad.47

Following Shuja ud-Daula’s death in 1775, Polier saw his alternative

employment with Shah Alam as a way to tackle his ambiguous status

in India. His recognition of Shah Alam’s sovereignty and status after

his ascension to the throne of Delhi in 1772 is further re-affirmed in

Polier’s biography of the emperor’s reign from 1771 through 1779.48

But as his personal correspondence shows, he was also keen to have

royal support for settling a number of outstanding property disputes

with Najaf Khan, Shah Alam’s primary aide. Well aware of the ongoing political uncertainties in the Mughal court, Polier saw himself as a

military advisor and aide to Shah Alam who would “…set right the

management of the Empire.”49 On 18 March 1776, Polier finally

gained an audience with the emperor and joined his service. Despite

his newfound employment, Polier’s letters communicate his impatience with the state of affairs in Delhi and the difficulty in securing a

diwan and other handymen to assist him.50 He was equally anxious to

46

Polier, Shah Alam II and his court. Ed. Pratul C. Gupta (1989), 7-9.

Folio 358a. Muzaffar Alam and Seema Alavi. A European Experience of the

Mughal Orient: The I�jaz-i Arsalani (Persian Letters, 1773-1779) of Antoine-Louis

Henri Polier (Oxford University Press: Delhi, 2001), 314.

48

Polier, Shah Alam II and his court.

49

The pargana of Khalilganj was assigned to Polier, which Najib Khan refused to

release to him. Polier was very anxious to recover the revenue from Khalilganj and

had solicited the help of Shah Alam to this effect. His frustration over the unresolved

matter of the jagir’s ownership is expressed throughout in his correspondence. Alam

and Alavi. European Experience.

50

“… I need a Bengali here to take care of my work at the court. Find out about

one and send him to me…This place is full of Kashmiris. However to me there is no

distinction between a Bengali and a Kashmiri. Look for someone capable of manag47

�miniatures to monuments picturing shah alam’s delhi

127

manage his household affairs and impart correct direction to painters

in his service there. Generally dissatisfied with the lack of supervision

of his painters in Avadh, Polier found it necessary to call the painters

to Delhi:

The painters are doing nothing these days. As a matter of fact, in the

absence of the masters it is difficult to get things done properly by the

servants. I therefore want these artists to be sent here.”51 “…I gather

that the artists are not doing good work after I left. Since I have been

ordered to stay here in Shahjahanabad it is necessary they join me

here.52

In this context, we are made aware of the all-important instance of

Polier directing his chef d’atelier Mihr Chand to join him in Delhi. In

a letter dated 27 March 1776, Polier asks Mihr Chand to, “… reach

here along with two other painters and one naqqash [decorator] who

should be a good person, skillful and keen to accompany you…53

Polier further instructs Mihr Chand to:

…Keep all the albums and qit�as in one box carefully so that they are

safe from the dust and do not get damaged in transit. Load them

together with the boxes for the Persian books and fix them there

(tightly). Also fix the cartage rates and arrive here with them without

delay.54

Polier’s personal correspondence confirms that Mihr Chand did

arrive in Delhi and carried with him a number of drawings and

albums. On 26 June 1776, Polier wrote to his diwan Manik Ram

acknowledging the painter’s arrival,

Mehrchand gave me your letter of 15 Rabi� II here on 6 Jumada I,

together with two chaupalas full of boxes of velvet, books and paintings, a bundle (ganth) of clothes and locked boxes (pitaris) with goods

from Faizabad…55

The arrival of Avadh artists in Delhi ca.1776 would have likely caused

a stir in the artistic circles at Delhi, however, there is no further written evidence in Polier’s correspondence to suggest that Mihr Chand

ing my work here efficiently.” 5 Safar Tuesday, Folio 368b. To Diwan Manik Ram.

Ibid., 322-23.

51

Folio 391b. Letter to Manik Ram. Ibid., 343.

52

Folio 396b, Ibid., 347.

53

Folio 373b. Letter to Mehrchand, the artist. Ibid., 326-7.

54

Folio 397b. To Mehrchand. Ibid., 348.

55

Folio 430a. Letter to Manik Ram. Ibid., 377.

�128

yuthika sharma

or any other artists from Avadh were received at the Mughal court or

commissioned to work for local patrons in Delhi. However, it is not

difficult to imagine the warm reception Mihr Chand would have

received especially since he had painted Shah Alam soon after his

accession to the throne in 1759 when the emperor was residing in the

eastern provinces. Mihr Chand’s portrait of Shah Alam titled, “Abu’l

Muzaffar Jalal al-din Shah Alam Badshah Ghazi,” (ca.1760-65) confirms in its use of the emperor’s formal titles, his regal status to the

fullest.56 The presence of the chatr (parasol), the Koran in the emperor’s hands as well as the use of the side profile reinforces the formality

of the composition.57 By 1765, a number of European collectors in

addition to Polier owned such portraits that were painted in cities

where Shah Alam had resided. (CP 6.9)58

A likely candidate for the unknown contents of Mihr Chand’s box

of paintings brought to Delhi is a set of five drawings of large-scaled

plans of Delhi currently held in the collection of the Victoria and

Albert Museum, London. Curiously enough, three of these five drawings are maps of the city of Shahjahanabad, executed on hand-scaled

paper in watercolor in a light wash, drawn on long scrolls such that all

three parts could be laid out to form a single composition. At the head

of this tripartite composition is a plan of the Red Fort followed by

two large-scaled plans of the main streets in Shahjahanabad—one

depicting Chandni Chowk (140 × 31cm) and the other, Faiz Bazaar

(135 × 31cm).59 The drawings are labeled in Persian with transliteration in English and Latin labels. The labels fall roughly into three

types—the well-known buildings such as mosques, baths and public

squares, the havelis and residences of nobles, and finally, the names of

trades carried on in various localities. The other two drawings,

56

See Museum für Islamiche Kunst, Berlin, Polier Album I.4594, fol. 32r, reproduced in Roy, “Origins of the Late Mughal Painting Tradition in Avadh” in India’s

Fabled City: The Art of Courtly Lucknow, ed. Stephen Markel (DelMonico, Prestel,

New York, 2010), 178, plate 115.

57

Losty’s suggests that Mihr Chand likely left Delhi at the same time as Shah

Alam’s departure to the east in 1758. Losty “Towards a New Naturalism”, 45. For

Mihr Chand’s employment with Polier see Malini Roy, “Some Unexpected Sources

for Paintings by the Artist Mihr Chand (fl. c. 1759-86), Son of Ganga Ram.” South

Asian Studies 26, No. 1, (March 2010): 21-29.

58

This portrait of Shah Alam II painted in Murshidabad is inscribed, “This picture given me by Hugh Acland 1764 F. T. H. (?),” See also Simon Ray Indian &

Islamic Works of Art, Cat. No. 24 (November 2009), 84-85.

59

Victoria & Albert Museum AL 1754; AL 1762; AL 1763. Archer, Company

Paintings, 132.

�miniatures to monuments picturing shah alam’s delhi

129

executed on hand-squared paper, clearly belong to another master

album of architectural drawings commissioned by Gentil in Faizabad

in 1774 titled, Palais indiens recueilles par M. Le Gentil, now held in

the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.60 The presence of the city maps with

the architectural drawings may initially indicate that the maps were

commissioned for Gentil. However, as further examination will show

Polier emerges as a more likely candidate for commissioning these

street maps of Delhi. Polier and Gentil were in the habit of sharing

drawings and paintings and often commissioned copies of a particular

work by the same artist.61 Thus it is not surprising to find drawings

from the Palais Indiens in this set.62 The three maps of Shahjahanabad

would have been an appropriate means of projecting Polier’s authority as a surveyor, fort engineer, and military strategist to Shah Alam at

Delhi and it is more likely that the maps were made for him.

It is remarkable that the three maps of Shahjahanabad are obvious

copies from a master version, one of which is the plan of the Red Fort

by Nidha Mal discussed earlier in this essay (CP 6.10). Susan Gole’s

thorough study of the V&A maps suggests that they were made

between 1751 and 1757, around the time of the raid of Delhi by

Ahmad Shah Abdali. Her analysis is based on the latest building illustrated in the map, which was the mosque of Javed Khan Nawab

Bahadur built in 1751. The maps also name important public places

such as the bath of Sa�ad ullah Khan, mosques, the Kotwali, and the

gate to the Begum’s garden.63 (B/W 6.11) It is self-evident that the

60

Two drawings, Dara Shikoh’s palace in Agra (Façade du Palais de Dara Cheka

du côte du Djemna à Agra 1774) and the plan of the Emperor’s Garden and Seraglio,

Delhi (Sérail et jardin du palais du grand Mughal à Dély) are undoubtedly contemporaneous with Palais Indiens and were probably dispersed from the original set

before Gentil compiled the album. There is also a third drawing, of the Jami Mosque

of Delhi, which is unlisted in the museum catalogue. For a fuller exposition of the

album, see Chanchal Dadlani, “The ‘Palais Indiens’ collection of 1774,” Representing

Mughal Architecture in Late-Eighteenth Century India” in Ars Orientalis, 39,

Globalizing Cultures: Art and Mobility in the Eighteenth Century (2010): 175-97.

61

On Thursday December 15, 1774 Polier wrote to one of his painters, possibly

Nevasi Lal: “The portrait of the Nawab [Shuja ud-Daulah] that you had sent for me

has been held back by Monsieur Gentil for himself. Make a similar portrait and keep

it for me. You shall be generously rewarded when I reach Faizabad if you do my

work with due care and attention.” See Folio 37a. Alam and Alavi European experience, 117.

62

For instance, the drawings are listed in Gentil’s inventory. Dadlani ‘Palais

Indiens’ collection of 1774, 175-97.

63

Susan Gole, ‘Three maps of Shahjahanabad,’ South Asian Studies, (1988):

13-27. Also see Susan Gole, ‘Plans of Indian Towns’ in Shahjahanabad/Old Delhi,

�130

yuthika sharma

dating is closer to the signed map by Nidha Mal, which also raises the

important question of not one but three paintings originally executed

successively by Nidha Mal in the 1750s forming the basis of the later

V&A set.64 The oblique reference to Nidha Mal’s death before 1772 in

Maratha correspondence, which is discussed earlier, is further evidence that the signed Red Fort map was done as a precedent to the

later copies.65 While we have no record of whether Nidha Mal worked

on any maps during the last decade of his career, his signature appears

on a number of later paintings from Avadh.66 The English inscription

“jurisdiction of Nuddha Mull,” on the earlier map from 1750 by Nidha

Mal accompanying his signature was most likely added to the painting

after it was brought into Avadh between 1760 and 1770.67 (CP 6.3)

Polier’s own experience in Delhi reveals much about his interest in

the city’s built environment. Polier occupied the haveli of wazir Safdar

Jang (father of Shuja ud-Daula) upon his arrival in Delhi, one of the

largest mansions originally part of Dara Shikoh’s haveli.68 He soon

Tradition and Colonial Change, eds. Thomas Ehlers and Eckart Krafft (Manohar,

2003), 128. Gole suggests that the street plans they seem to have been drawn at eye

level by someone walking along the centre of each street.

64

Joseph E. Schwartzberg, ‘South Asian Cartography,’ in The history of cartography. Vol.2. Book 1: Cartography in the traditional Islamic and South Asian societies,

eds. J. B. Harley and David Woodward (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992),

468-469.

65

The dating is further substantiated by the painting’s provenance. It was part of

the collection of Robert Orme and acquired by India Office after his death in 1801.

Since Orme left India for England in 1758 he must have acquired this painting

before. It is inscribed incorrectly on reverse: ‘Orme. Fort� (‘Palace) at Agra, MS�;

numbered ‘39�; and: ‘No.21, Agra fort.� See British Library Add.Or. 1790. For the life

and career of Orme, see Sinharaja Tammita Delgoda, “Nabob, Historian and Orientalist” Robert Orme: The Life and Career of an East India Company Servant (17281801) Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, Third Series 2, (November, 1992): 363-376.

The drawing is not mentioned in Hill (1916), which does pose an interesting possibility that it was added to the collection at a later date.

66

See for instance, “Two noblemen smoking a huqqa on a terrace,” Bharat Kala

Bhavan, Varanasi; “Night scene showing nobles and courtiers entertained by female

musicians,” Collection of Cynthia Polsky, New York. See also Roy, “Late Mughal

Painting Tradition,” 165-186.

67

Falk and Archer, Indian Miniatures, 121.

68

Polier writes: “At present I am living in the haveli of late Nawab Safdar Jang. I

am honored to be in the service of the Emperor. 5 Safar Tuesday (25 March 1776).

Alam and Alavi, European Experience, 324. Gentil in his emoirs noted that Safdar

Jang bought Dara Shikoh’s Palace at a modest price during the reign of Ahmad Shah.

See Mémoirs (1822), 379; Gole, ‘Plans of Indian Towns’. Stephen Blake suggests that

Safdar Jang’s Haveli was a part of a two-part division of Dara Shikoh’s Palace,

divided during the late seventeenth or early eighteenth century possibly during

Nadir Shah’s invasion. It was inhabited by Najib ud-Daula, the Afghan leader

�miniatures to monuments picturing shah alam’s delhi

131

vacated Safdar Jang’s haveli to move to Itimad ud-Daula’s (Qamar alDin Khan’s) haveli in Delhi. 69 This move allowed Polier to inhabit one

of the most prestigious havelis in the city. This was the haveli of

Muhammad Shah’s wazir Qamar al-Din Khan (wazir from 1724-48),

who was titled Itimad ud-Daulah II. Polier was struck by the irony of

his residing in this mansion, while Qamar al-Din’s surviving son was

living in a ‘wretched dwelling on the outside of this house, which, in

the time of his father, one of his servants would have disdained to live

in.�70 However, Polier’s description of it as a lackluster building in disrepair points to the contrast that he must have experienced from his

dwellings in Faizabad that he had taken pains to furnish and decorate.71 This impression of new residence in Shahjahanabad was largely

reflective of his disappointment with the city itself, which in Polier’s

opinion possessed only a few noteworthy features. The only structures

that impressed Polier were the Jami Mosque and the ‘regular’ street of

Chandni Chowk, which compared well to a French or English avenue.72 It is possible that the two street plans of Chandni Chowk and

Faiz Bazaar would have appealed to Polier precisely because they

were planned as rectilinear streets. (These, along with the square plan

of the Red Fort appear to recast the city’s layout as if derived from a

trigonometric survey, well before one was begun for Delhi in the last

decade of the eighteenth century. (B/W 6.12)73 Polier’s commissions

of aerial views of the Red Fort recasting it within a rectilinear format,

Ahmad Shah Abdali’s appointee in India between 1755-57 and then again from

1761-1770 following Abdali’s victory at Panipat. Blake, Shahjahanabad 75.

69

Safdar Jang’s mansion had been the center of much political intrigue. It was

also the site of the murder of Javed Khan, the court eunuch, in 1752.The masjid of

Nawab Bahadur built by Javed Khan in 1751 forms the anchor point for dating the

map by Susan Gole. Gole also points out that the house of Javed Khan near Delhi

Gate next to the city wall, labeled in the map, was used by the Marathas to break into

the city in 1760. As quoted in Sarkar, (1932-50) Vol. II, 253.

70

A.L.H. Polier, Miscellaneous Tracts, Extracts of Letters from Major Polier at

Delhi to Col. Ironside at Belgram, May 22, 1776, Asiatic Annual Register 2 (1800):

29-30. Blake, Shahjahanabad, 79.

71

Take for instance Polier’s detailed instructions to his handyman Oshra Gora

Mistri for furnishing and decorating his haveli in Faizabad. Folio 115a. Alam and

Alavi, European Experience, 324.

72

Polier, ‘Extracts of Letters’.

73

For a later map of Shahjahanabad that also conforms to a geometric layout see,

“Trigonometrical Survey of the Environs of Delhy or Shah Jehanabad, 1808” British

Library Asia and Pacific Collection, Cat. No. E. VII. 20, size 71 × 84 cm. Another

map titled ‘Plan of Dehly Reduced from a large Hindostanny Map of that City,

1800?’” also depicts the city wall as a square plan.

�132

yuthika sharma

privileging axial views into the palace grounds from the main entrance.

A view of the Red Fort from an album that Polier compiled for Lady

Coote, widow of General Eyre Coote (died 1783), Commander in

Chief under Warren Hastings ca.1785, shows the general life in the

Fort in isometric views. In the foreground the foreshortened figure of

Shah Alam is shown entering the Diwan-i-Khas while to the left female

figures occupy the grounds of the Rang Mahal and other buildings

alongside. In the near distance soldiers walk in ranks and people mill

about their daily tasks. The view is oriented from the eastern face of

the Red Fort, with the Shah Burj and the Naqqar Khana in virtual

alignment. (CP 6.13)74

Concluding a Journey: Bazgasht Imagery and the Red Fort

In the prelude to Shah Alam’s return to Delhi, the Mughal fortress

became the center of much discussion and political intrigue. Shah

Alam II’s ‘Royal resolution,’ to march from Allahabad towards Shahjahanabad, was a source of much consternation to the British East India

Company and their allies in Avadh and Bihar.75 As William Francklin

wrote, “…even from the moment of his settlement at Allahabad, ” he

“sighed in secret for the pleasures of the capital, and was ambitious of

re-ascending the throne of his ancestors.”76 Entreaties from the

Company’s Commander-in-Chief General Robert Barker were laid to

the wayside, as the Mughal emperor confirmed his alliance with

Maratha chiefs who had promised the deliverance of the Delhi fort to

him. For the British, this return implied a ‘hazardous undertaking’

that would have found them confronting the Marathas, who posed an

immediate threat to their own territorial ambitions.77 Moreover, the

‘movement of the royal standard towards the capital, it was feared,’

74

This drawing measuring 28.2 × 41.7 cm is executed in ink, transparent and

opaque watercolor, and gold and is mounted on to an ornamental border also in the

same medium. Achenbach Foundation for Graphic Arts, Fine Arts Museum of San

Francisco (FAMSF), 1982.2.70.9. Another copy of this view in the British Library

lacks the trellis framing the view, and indicates the production of multiple copies of

this image. See Add. Or. 948. copy of this album compiled by Polier is in the

Museum of Islamic Art, Berlin. For a discussion of the album see, J. Bautze, Interaction of Cultures: Indian and Western Painting, 1780-1910 (Virginia, 1998), 252-54.

75

December 14, 1770. Calendar of Persian Correspondence, Vol. III (Calcutta,

1919).

76

Francklin, Reign of Shah-Aulum, 26.

77

April 22, 1771 Persian Correspondence, April 22, 1771.

�miniatures to monuments picturing shah alam’s delhi

133

would leave the occupation of the Allahabad fort open to wazir Shuja

ud-Daula’s designs on it and cause further ambiguity in terms of its

ownership. 78

These discussions based on Shah Alam’s resolve to move to Delhi

form the subtext of two processional scenes painted by Avadh artists

showing instances from the return journey that the Mughal court and

household undertook from Allahabad to Delhi. In the first procession

set along the banks of a river, Shah Alam is seated on his elephant

howdah surrounded by his standard bearers and his retinue of soldiers approaching a fort to the left.79 The documentary content of the

procession scene allows us to date it to a period between 1770-1775,

perhaps documenting the movement of the Mughal court from

Allahabad to Delhi.80 A more significant painting is an all-encompassing view of Shah Alam’s procession approaching the fortifications of

Shahjahanabad, which provides an insight into the moment of the

emperor’s arrival at Delhi embodying the penultimate phase of the

‘Royal resolution�. Painted in the last quarter of the eighteenth century

the painting highlights, in both spatial and temporal terms, the symbolic importance of the royal procession’s arrival at Delhi (CP 6.14).

The unfolding of the winding movement of the royal cortege from left

to right along the banks of the river Jamuna, leading to the the eastern

face of the Red Fort at Shahjahanabad, conveys its progress over time.

In the immediate foreground the presence of the East India Company

soldiers escorting the covered palanquins and howdahs of ladies of the

royal household suggests that the painting was possibly made to highlight the Company’s role in facilitating the Mughal emperor’s move to

Delhi.81 Any signs of the emperor’s collusion with the Marathas are

conveniently omitted.

In addition to being the sole historical record of Shah Alam’s

bazgasht (return) to Delhi, this painting is also easily the most visible endorsement of topographical genre in the service of imperial

identity in the later Mughal period. On closer inspection we find that

the Fort buildings along the eastern front of the Jamuna are carefully

78

Ibid.

“The Royal Procession of Shah Alam II”, here ascribed a revised date of ca.

1776 V&A Museum IS 38-1957. Archer, Company Paintings 124, No. 91.

80

Ibid., 124.

81

Shah Alam sent a shuqqa asking General Barker for a force to accompany his

procession to Delhi, a request that was obliged. Dec 14, 1770. Persian Correspondence, Vol. III. The left to right directionality of the procession and the numbering

indicates that it would have been commissioned by a European patron.

79

�134

yuthika sharma

delineated with numbers to a form a panorama of the fort and its surroundings, with the Qutb Minar on the extreme left and the Salimgarh

Fort on the right. The royal enclosures and audience halls rendered in

three dimensions are shown within the walls of the Red Fort, with the

prominent gilded dome of the Shah Burj within the imperial apartments prominently in view of the approaching cavalcade. This panoramic view of the fort city and its environs reinforces Mughal Delhi

as the desired destination of the emperor. This view may well be one

of the earliest attempts at an architectural panorama of Delhi along

the riverfront, a view which was to achieve much popularity in the

coming decades. The intentional numbering of the buildings along the

fort wall highlights the documentary interest of the patron, which

further reinforces the importance of the Red Fort to the historic

bazgasht of Shah Alam.82

The selection of paintings discussed in this essay highlight the way

in which the architectural view of the Red Fort of Shahjahanabad

often served as a visual encapsulation of power, as the seat of the lateMughal empire. Created by Mughal painters and their descendants

who worked as mapmakers and topographers, such visuals allow us to

recast these artists as innovators of spatial frameworks within paintings in later Mughal Delhi. As the various topographical drawings

of Delhi discussed in this essay demonstrate, the projection of

Shahjahanabad as a site of imperial significance was often the result of

the “…artist’s layering of motifs from heterogeneous pictorial traditions…to legitimate the site as a locus of power both sacred and

secular.”83 In the various pictorial representations of Delhi, the artist’s

use of cartographic methods also worked to alter the logic of the city,

which is now negotiated by relative placement of buildings and figures, labeling, and by the hierarchical sizing of elements within it.

The view of Shah Alam’s return to Shahjahanabad in 1772 appears

as a ringing endorsement of the Red Fort as the seat of the laterMughals. In the painting, the Red Fort embodies the idea of Shah

82

Mildred Archer has suggested that this painting is very similar to those in the

Recueil made for Gentil in Faizabad in 1774. See Archer, Company Paintings, 124,

No. 91.

83

In a parallel scenario, Debra Diamond has shown how the representation of

new towns around Jodhpur such as Mahamandir (ca. 1803) often borrowed visual

conventions from existing devotional painting, pilgrimage maps, and town plans.

“The Cartography of Power: Mapping genres in Jodhpur Painting” in Arts of Mughal

India, ed. Rosemary Crill, et. al., 280-82 (London: Victoria & Albert Museum, 2004),

pp. 280-282.

�miniatures to monuments picturing shah alam’s delhi

135

Alam’s bazgasht, a solitary bastion of Mughal sovereignty in a fragmented political domain. By 1803, the British East India Company,

under General Gerard Lake, defeated the Maratha army at Laswari

and took over the effective administration of Delhi. Conventional wisdom has attributed to the British occupation of Delhi the renaissance

of all artistic activity. Topographical painting in Delhi, too, is primarily understood with respect to the rise of the school of Company

painters, who worked for British Residents and officials such as David

Ochterlony, William Fraser, and James Skinner.84 The piecemeal

scholarship on painters employed by the later Mughal court at Delhi

has discouraged a substantive view into the painting culture in this

period, and into the role of artists who brought together local and

European conventions of cartography. While these paintings may not

have closely adhered to either Mughal or European conventions, nevertheless they remained a means of projecting Delhi's pre-eminence as

the seat of the Mughal authority in the troubled eighteenth century.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Catherine B. Asher, Vidya Dehejia, Finbarr

Barry Flood, Susan Gole, Karen Leonard, Alka Patel, and Susan

Stronge for their reviews and comments on earlier drafts of this essay.

Bibliography

Calendar of Persian Correspondence, Vol. I, II, III. Calcutta: Superintendent Government Printing, India, 1919.

Itihasa Sangraha Aitihasik Tipane, no. 11. Satara (India), September, 1908.

Aitken, Molly Emma. “Parataxis and the Practice of Reuse: From Mughal Margins to

Mir Kalan Khan” Archives of Asian Art 59 (2009) 81-103.

Alam, Muzaffar and Seema Alavi. A European Experience of the Mughal Orient: The

I�jaz-i Arsalani (Persian Letters, 1773-1779) of Antoine-Louis Henri Polier. Oxford

University Press: Delhi, 2001.

Allingham, William. The new method of fortification, as practised by Monsieur de

Vauban engineer-general of France. Together with a new treatise of geometry. The

84

For instance, see Mildred Archer, Company Drawings in the India Office

Library (1972). The topographical school of painting is seen to have matured fullscale in 1815, fueled in part by the earlier visit of painters such as Thomas and

William Daniell (in Delhi 1788-89) and a synonymous interest in architectural conservation. See J.P. Losty, ‘The Delhi Palace in 1846: a Panoramic View by Mazhar

�Ali Khan’, in Arts of Mughal India; Studies in Honour of Robert Skelton, 286-302

(London: Victoria & Albert Museum, 2004).

�136

yuthika sharma

fourth edition, carefully revised & corrected by the original. ... By W. Allingham, ...

London, 1722.

Archer, Mildred. “Tilly Kettle and the Court of Oude (1772-1778)” Apollo, (February

1972): 96-106.

———., Company Paintings: Indian Paintings of the British Period. London: Victoria &

Albert Museum, 1992.

Bautze, Joachim. Interaction of Cultures: Indian and Western Painting, 1780-1910.

Virginia: Art Services International, 1998.

Baryiski, Patricia Bahree. “Painting in Avadh in the 18th Century.” In Islam and

Indian Regions, edited by A.L. Dallapiccola and S.Z.-A. Lallemant, Vol. I, 351-66,

Vol. 2, plates 31-40. Stuttgart, 1993.

Bernoulli, Jean, ed. Description historique et géographique de l’Inde, 3 Volumes. Berlin:

Pierre Bordeaux, 1786-8.

Bhandari, Sujan Rai. Khulasat-ut-Tawarikh, edited by Ed. Zafar Hasan. Delhi, 1918.

Blake, Stephen. Shahjahanabad: The sovereign city in Mughal India 1639-1739.

Cambridge, 1993.

Cohen, Monique, Amina Okada, Francis Richard. A la cour du Grand Moghol. Paris:

Bibliothèque Nationale, 1986.

Diamond, Debra. “The Cartography of Power: Mapping genres in Jodhpur Painting.”

In Arts of Mughal India, edited by Rosemary Crill et al., Victoria & Albert Museum,

Ahmedabad, India: Mapin, 2004.

Dadlani, Chanchal. “The ‘Palais Indiens’ collection of 1774: Representing Mughal

Architecture in Late-Eighteenth Century India” Ars Orientalis, Vol. 39, Globalizing

Cultures: Art and Mobility in the Eighteenth Century, edited by Nebahat Avcıoğlu

and Finbarr Barry Flood. (2010): 175-97.

Delgoda, Sinharaja Tammita. “ “Nabob, Historian and Orientalist” Robert Orme: The

Life and Career of an East India Company Servant (1728-1801)” Journal of the

Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland, Third Series 2, (November, 1992).

Eaton, Natasha. “Critical cosmopolitanism: gifting and collecting art at Lucknow,

1775-97” Art and the British empire, edited by Timothy Barringer et al., 189-204.

Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2007.

Edney, Matthew H. Mapping an Empire: The geographical construction of British

India. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990.

Emmett, Robert C. “The Gazetteers of India.” M.A. Thesis, University of Chicago,

1976.

Falk, Toby and Mildred Archer. Indian Miniatures in the India Office Library.

London: Sotheby Parke Bernet, 1981.

Fazl, Abu’l. Ain-i Akbari, Vol. I translated by H. Blochman. Calcutta: Asiatic Society

of Bengal, 1927, reprint 1965.

Francklin, William. History of the reign of Shah-Aulum (1798).