A self-conscious woman juggles adjusting to her new role as an aristocrat's wife and avoiding being intimidated by his first wife's spectral presence.A self-conscious woman juggles adjusting to her new role as an aristocrat's wife and avoiding being intimidated by his first wife's spectral presence.A self-conscious woman juggles adjusting to her new role as an aristocrat's wife and avoiding being intimidated by his first wife's spectral presence.

- Won 2 Oscars

- 7 wins & 10 nominations total

Bunny Beatty

- Maid

- (uncredited)

Billy Bevan

- Policeman

- (uncredited)

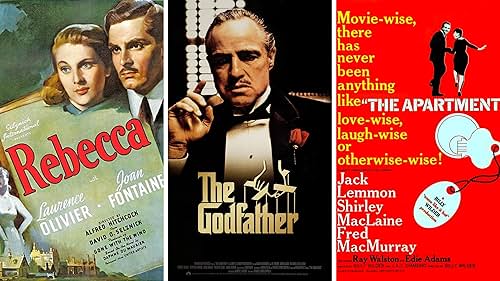

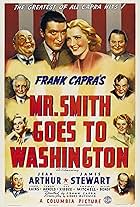

Best Picture Winners by Year

Best Picture Winners by Year

See the complete list of Best Picture winners. For fun, use the "sort order" function to rank by IMDb rating and other criteria.

Storyline

Did you know

- TriviaPer Sir Alfred Hitchcock's instructions, Dame Judith Anderson rarely blinks her eyes while playing Mrs. Danvers.

- GoofsThe oath taken by the policeman at the inquest is incorrect. He quietly adds 'So help me God' at the end. These words are not used in the UK.

- Quotes

[the new Mrs. de Winter wants to dispose of Rebecca's letters]

The Second Mrs. de Winter: I want you to get rid of all these things.

Mrs. Danvers: But these are Mrs. de Winter's things.

The Second Mrs. de Winter: *I* am Mrs. de Winter now!

- Crazy creditsThe original 1940 credits read "Selznick International presents its picturization of Daphne Du Maurier's 'Rebecca'". The credits on the re-issue version read "The Selznick Studio presents its production of Daphne Du Maurier's 'Rebecca'".

- Alternate versionsThe opening credits were re-done (with different font) for the 1950's re-release of the movie. It is these credits that have turned up on all telecasts of the film (even as recently as 2013) and all previous video releases. The Criterion release (which is now only available through outlet stores) restores all of the credits to their original form.

- ConnectionsEdited into The Last Tycoon: Pilot (2016)

- SoundtracksLove's Old Sweet Song (Just a Song at Twilight)

(1884) (uncredited)

Music by J.L. Molloy

Hummed by Joan Fontaine

Featured review

"Rebecca" was the first Hitchcock film I ever saw, and I was mesmerized by it from the start, convinced that I had to see more of the director's work. It richly deserved the Oscar it received, but it's a real puzzle that the Academy saw fit to withhold a best director award for Hitch. Would one possibly give an award to a work by Picasso and not to Picasso himself?

"Rebecca" was the first of the director's American-made films, and it shows. It's quite different from his earlier British-made films, such as "Young and Innocent" and even "The Lady Vanishes," which somehow seem more amateurish by comparison. (I know little of the British cinema of that era, but it's difficult not to conclude that Hollywood was better at producing more sophisticated efforts.) I would even judge "Rebecca" the best of his films of the early 1940s, with the possible exception of "Shadow of a Doubt." It is true, of course, that much of this film has become cliché (remember the spoofs on the old "Carol Burnette Show"!), but it still weathers the decades very well. The acting is uniformly excellent. Olivier is the hardened Maxim de Winter, untitled lord of Manderly, trying to forget the past and given to unexpected bouts of anger and coldheartedness. Fontaine is perfect as the unnamed mousy heroine, innocent yet deeply in love, still carrying with her the aura of an awkward schoolgirl. Even character actor Nigel Bruce, best known for his role in the Sherlock Holmes films, makes an appearance and plays, in effect, Nigel Bruce!

But it is Judith Anderson's role as Mrs. Danvers that viewers are likely to remember best. Her presence is as dark and foreboding as that of the deceased Rebecca herself, and Fontaine is evidently cowed by her icy stare and unnervingly formal manner. The dynamics between the two actresses are wonderful. Who could fail to empathize with Fontaine's unenviable position as, in effect, the new employer of such an intimidating personage? On the other hand, Olivier seems quite unfearful of Anderson, despite her representing so much of the past he is trying to block out. This part of the plot (even in the book) never made much sense to me and is unconvincing.

As far as I know, this film marked Hitch's first collaboration with composer Franz Waxman, whose haunting score makes it all the more memorable. Waxman's scores are perhaps less obviously cinematic than those of the incomparable Bernard Herrmann, who would score Hitch's films from 1955 to 1966. Contrast the score for "Rebecca" to Herrmann's music for "Citizen Kane" the following year, and you'll immediately hear the difference. Waxman's is more symphonic in the central European style reflective of his own birth and upbringing. Yet it is worth recalling that scoring films was still a new art at this time, and both Waxman and Herrmann were pioneers.

Finally, one has to mention the cinematography, which is magnificent. Technically "Rebecca" might have been filmed in colour, which was newly available in 1940. ("Gone with the Wind" was filmed entirely in colour the previous year, while "The Wizzard of Oz" and "The Women" had colour scenes.) But colour would have diminished its impact. The suspense and the ominous sense of impending doom could only have been communicated through the medium of black-and-white and the deft use of light and shade which it affords.

In one respect, of course, "Rebecca" is not a typical Hitchcock film. There is no fleeing innocent trying to clear his name of a crime he did not commit. Surprisingly, there isn't even a murder, although its absence was apparently imposed by the Hayes Code and is certainly foreign to Daphne du Maurier's original novel. Some have said that there is more Selznick than Hitchcock in this film, and perhaps there's something to that. Still, if the collaborative effort between the two was not exactly amiable, it was nevertheless successful.

In short, this is the first in a string of Hitchcock masterpieces.

"Rebecca" was the first of the director's American-made films, and it shows. It's quite different from his earlier British-made films, such as "Young and Innocent" and even "The Lady Vanishes," which somehow seem more amateurish by comparison. (I know little of the British cinema of that era, but it's difficult not to conclude that Hollywood was better at producing more sophisticated efforts.) I would even judge "Rebecca" the best of his films of the early 1940s, with the possible exception of "Shadow of a Doubt." It is true, of course, that much of this film has become cliché (remember the spoofs on the old "Carol Burnette Show"!), but it still weathers the decades very well. The acting is uniformly excellent. Olivier is the hardened Maxim de Winter, untitled lord of Manderly, trying to forget the past and given to unexpected bouts of anger and coldheartedness. Fontaine is perfect as the unnamed mousy heroine, innocent yet deeply in love, still carrying with her the aura of an awkward schoolgirl. Even character actor Nigel Bruce, best known for his role in the Sherlock Holmes films, makes an appearance and plays, in effect, Nigel Bruce!

But it is Judith Anderson's role as Mrs. Danvers that viewers are likely to remember best. Her presence is as dark and foreboding as that of the deceased Rebecca herself, and Fontaine is evidently cowed by her icy stare and unnervingly formal manner. The dynamics between the two actresses are wonderful. Who could fail to empathize with Fontaine's unenviable position as, in effect, the new employer of such an intimidating personage? On the other hand, Olivier seems quite unfearful of Anderson, despite her representing so much of the past he is trying to block out. This part of the plot (even in the book) never made much sense to me and is unconvincing.

As far as I know, this film marked Hitch's first collaboration with composer Franz Waxman, whose haunting score makes it all the more memorable. Waxman's scores are perhaps less obviously cinematic than those of the incomparable Bernard Herrmann, who would score Hitch's films from 1955 to 1966. Contrast the score for "Rebecca" to Herrmann's music for "Citizen Kane" the following year, and you'll immediately hear the difference. Waxman's is more symphonic in the central European style reflective of his own birth and upbringing. Yet it is worth recalling that scoring films was still a new art at this time, and both Waxman and Herrmann were pioneers.

Finally, one has to mention the cinematography, which is magnificent. Technically "Rebecca" might have been filmed in colour, which was newly available in 1940. ("Gone with the Wind" was filmed entirely in colour the previous year, while "The Wizzard of Oz" and "The Women" had colour scenes.) But colour would have diminished its impact. The suspense and the ominous sense of impending doom could only have been communicated through the medium of black-and-white and the deft use of light and shade which it affords.

In one respect, of course, "Rebecca" is not a typical Hitchcock film. There is no fleeing innocent trying to clear his name of a crime he did not commit. Surprisingly, there isn't even a murder, although its absence was apparently imposed by the Hayes Code and is certainly foreign to Daphne du Maurier's original novel. Some have said that there is more Selznick than Hitchcock in this film, and perhaps there's something to that. Still, if the collaborative effort between the two was not exactly amiable, it was nevertheless successful.

In short, this is the first in a string of Hitchcock masterpieces.

Details

Box office

- Budget

- $1,288,000 (estimated)

- Gross worldwide

- $113,328

- Runtime2 hours 10 minutes

- Color

- Aspect ratio

- 1.37 : 1

Contribute to this page

Suggest an edit or add missing content