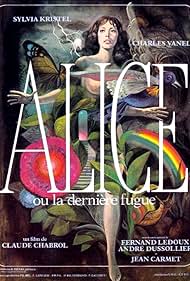

I expected a film with a protagonist named "Alice Carroll" to have something to do with Lewis Carroll's Alice books, but Claude Chabrol's "Alice or the Last Escapade" (although it seems a mistranslation to me to go from "fugue" to "escapade") reminds me more of Luis Buñuel's "The Exterminating Angel" (1962) and seems to have more in common with a different book, which this film's Alice reads in one scene, Jorge Luis Borges's "Fictions." That would explain the quasi-surrealism, labyrinth and purgatory-like entrapment and genre elements closer to horror than to the fairy tales of Carroll. Besides the one character's name, I didn't see much here beyond a checkered floor pattern or a somewhat small door and a generally strange place and characters suggesting that the film took inspiration from the Alice books. It's not an especially egregious bait-and-switch in this regard, although it's a travesty to cite Alice for a film that also reads largely as a reactionary revenge fantasy on the era's politics of second-wave feminism.

Allow me to elaborate. The picture begins with the male gaze (the concept of the "male gaze," itself, being a product of feminist film theory of the same era as this film--within a couple years, in fact, as Laura Mulvey penned her essay "Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema" in 1975), as Alice's beau is watching TV. While doing so, he calls upon Alice to listen to him complain about his day. Fed up with this male-centric gaze and storytelling, she announces that she's leaving him. He assumes she's being hysterical (a more accurate reading of the "fugue" in the title, I suspect, with all the misogynistic connotations of diagnosing women "hysterical") and warns her against leaving that night. Undeterred, Alice drives off on her own escapade, but her being a female driver in a man's movie, she soon crashes the car. A film-within-the-film of her emotional reflections is even played out on the windshield before the glass is broken--suggesting the incident has more to do with the emotional storm inside her than with the rainy weather outside.

Alice takes shelter in a mansion in what turns out to be something of a twist on the haunted, old-dark-house formula. The strange men she meets here inform her that she's trapped there and that her state of affairs is a source of amusement for them. In other words, she's found herself the subject of the male gaze, of which she cannot escape. She's confined in a film, with the mansion its theatre. This is, perhaps, most striking in a sequence that would otherwise seem to be a display of gratuitous nudity, as Alice stands seemingly alone in her room with a disembodied voice speaking to her. She tries to cover herself from an unseen gaze. Who's subjugating her with this voyeurism? We, the spectator, are.

This is such a well-constructed bit of reflexive composition centered on the cinematographic apparatus--its gaze and, thus, our gaze. It makes for a more engaging picture than the questionable ideology and trite sexism displayed would otherwise deserve.