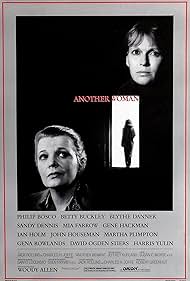

Facing a mid-life crisis, 50-year-old college dean Marion Post takes a sabbatical and rents an apartment next to a psychiatrist's office to write a new book, then is drawn to the plight of a... Read allFacing a mid-life crisis, 50-year-old college dean Marion Post takes a sabbatical and rents an apartment next to a psychiatrist's office to write a new book, then is drawn to the plight of a pregnant woman seeking that doctor's help.Facing a mid-life crisis, 50-year-old college dean Marion Post takes a sabbatical and rents an apartment next to a psychiatrist's office to write a new book, then is drawn to the plight of a pregnant woman seeking that doctor's help.

- Awards

- 1 win & 3 nominations

- Director

- Writer

- All cast & crew

- Production, box office & more at IMDbPro

Storyline

Did you know

- TriviaWoody Allen is not known for complimenting his actors, saying that the fact that he casts them is proof that he considers them great. However, he has said that the scenes between Gena Rowlands and Gene Hackman, particularly in the flashback of the party, were "electrifying."

- GoofsWhilst it is true that the tune of Gymnopédie No. 1 is played at the beginning of the film, it is not the piano version but rather the orchestral version orchestrated by Debussy. For some unknown reason, Debussy changed the numbers of the Gymnopédies: thus the orchestral version of Gymnopédie No. 3 bears the tune of Gymnopédie No. 1!

- SoundtracksGymnopédie No 1

Music by Erik Satie

Performed by Orchestre de la Société des Concerts du Conservatoire

Conducted by Louis Auriacombe

Courtesy of EMI Pathé-Marconi/Capitol Records Special Markets

Featured review

If there is a moral to Woody Allen's ANOTHER WOMAN, it is that we should live our lives with passion, spontaneity and optimism. Ironically, these are the very elements that are noticeable missing from the film. ANOTHER WOMAN seems to be selling products it doesn't have in stock, let alone on display.

ANOTHER WOMAN is an immaculate movie; sensitively acted, concisely written and lovingly filmed. But like so many of Allen's "serious" films, it is cold and strangely impersonal. It is Woody standing back and looking at someone else's life, composing a precise picture, but with a hands-off, leave-no-fingerprints approach. It is one of those films that is so easy to admire, but very difficult to embrace. It desperately wants to touch you, but refuses to come within touching distance. The film's central character is described thus: "She's just a little judgmental. You know, she sorta stands above people and evaluates them." That is how Allen approaches his characters here, like they're specimens.

There is, of course, two Woody Allens: the comedy genius and the always aspiring dramatist. Most of his comedies are pretty good, but the best are those that let the serious Woody sneak into the film and give the material backbone, as in ANNIE HALL, MANHATTAN, STARDUST MEMORIES and DECONSTRUCTING HARRY. He allows the serious Woody to make cameo appearances in his comedies, but when he sets his sites on meaningful drama, the funny Woody is barred from the set. It is as though Allen is afraid that so much as a smile will break the mood and make people forget just how serious his intentions are. He so easily mocks intellectual thought in his comedies, that he seems to have no faith in his ability to "be serious" and mean it. As such his serious comedies are alive and filled with insight, while his serious dramas are filled with pretense. How seriously can one take a line like "I shouldn't have seduced you. Intellectually, that is."? I mean, who the heck talks like that? In his comedies, such dialogue shows how pretentious the characters are; in his dramas, it seems meant to show just how sincere the characters are.

And words are an important element of ANOTHER WOMAN. Allen's dialogue and narration is eloquent and sophisticated, but stiff and formal. Even when discussing their deepest feelings or expressing anger or reliving joyous moments in their lives, all the characters speak as though they are discussing the terms of their life insurance policies. There is a solemn emptiness to the tone of the film; even at the end, when Marion tries to make amends for past failings, she seems to be negotiating a contract, not saying "Let's start again." Such pompous droning seems designed to reflect the tone of the characters' lives; but the end result is monotonous and deadening, rather than being poetic and compelling.

The film does have a clever conceit: the always marvelous Gena Rowlands plays Marion Post, a professor of philosophy, who sublets an apartment to serve as an office where she can write her latest book. A quirk in the ventilation system allows her to inadvertently eavesdrop on the conversations going on next door. The next apartment is the office of a psychiatrist, who counts among his patients a young pregnant woman, played by Mia Farrow. The young woman discusses at length her sorrowful life and suicidal impulses. Because she identifies with the younger woman's feelings of loneliness and alienation, Marion becomes obsessed with eavesdropping on the sessions and uses the situation as a springboard for reevaluating her own life.

It is significant that just as Allen tells the story from a sterile distance, Marion reviews her life only indirectly, though voice-overs, flashbacks, dreams and even symbolic stage productions. Even her psychoanalysis is conducted through a surrogate, Farrow's character, who is rather obviously named Hope. Much of the interaction with other characters occurs in Marion's mind. And rather predictably, Marion's journey of self discovery is, well, rather predictable. She discovers -- as protagonists in this sort of film always discover -- that her successful career and her well-ordered life are a facade hiding her empty relationships and assorted personal failures. Her life of satisfied accomplishment is meaningless and the trust, love and respect she believes she shares with others are delusions. It's like IT'S A WONDERFUL LIFE in reverse: Just as the angel Clarence acts as George Bailey's conscience to show him how valuable his life has been, Hope acts as Marion's conscience to reveal how empty her life as become.

ANOTHER WOMAN has a counterpart in Allen's 2003 film, ANYTHING ELSE; another film with an obvious doppelganger. The former is about a woman who encounters her younger alter ego and reevaluates her past choices, while the latter is about a young man whose encounters with his older alter ego (played by Woody Allen) effects the choices that will shape his future. The same basic story is approached from opposite directions.

It's dangerous to speculate, but it seems that Allen made ANOTHER WOMAN during a time in his life when he was hugely admired for his accomplishments and he was deeply involved in a relationship with Mia Farrow and her extended family. Certainly Farrow's playing a pregnant woman and Marion's second thoughts over placing career over personal relationships seem to suggest a parallel. By contrast, ANYTHING ELSE, made a decade and a half later, finds Allen's character playing a mentor at a time when he is apparently happily married to a much younger woman, and where his status as a filmmaker is more iconic than in vogue. As such, his surrogate changes from being the central figure to the sadder but wiser voice of experience.

Both films are steeped in regret, but make an effort to end in an upbeat fashion. But while ANOTHER WOMAN is an accomplished, polished work striving for a cool perfection, it is not persuasive in its attempt to inspire us with optimism. ANYTHING ELSE is rambling and unfocused and, well, sloppy, but its optimism is honest and funny. ANOTHER WOMAN is about getting another chance, but there is no reason to believe that anything will really change in Marion's tight, introspective little life.

ANOTHER WOMAN is an immaculate movie; sensitively acted, concisely written and lovingly filmed. But like so many of Allen's "serious" films, it is cold and strangely impersonal. It is Woody standing back and looking at someone else's life, composing a precise picture, but with a hands-off, leave-no-fingerprints approach. It is one of those films that is so easy to admire, but very difficult to embrace. It desperately wants to touch you, but refuses to come within touching distance. The film's central character is described thus: "She's just a little judgmental. You know, she sorta stands above people and evaluates them." That is how Allen approaches his characters here, like they're specimens.

There is, of course, two Woody Allens: the comedy genius and the always aspiring dramatist. Most of his comedies are pretty good, but the best are those that let the serious Woody sneak into the film and give the material backbone, as in ANNIE HALL, MANHATTAN, STARDUST MEMORIES and DECONSTRUCTING HARRY. He allows the serious Woody to make cameo appearances in his comedies, but when he sets his sites on meaningful drama, the funny Woody is barred from the set. It is as though Allen is afraid that so much as a smile will break the mood and make people forget just how serious his intentions are. He so easily mocks intellectual thought in his comedies, that he seems to have no faith in his ability to "be serious" and mean it. As such his serious comedies are alive and filled with insight, while his serious dramas are filled with pretense. How seriously can one take a line like "I shouldn't have seduced you. Intellectually, that is."? I mean, who the heck talks like that? In his comedies, such dialogue shows how pretentious the characters are; in his dramas, it seems meant to show just how sincere the characters are.

And words are an important element of ANOTHER WOMAN. Allen's dialogue and narration is eloquent and sophisticated, but stiff and formal. Even when discussing their deepest feelings or expressing anger or reliving joyous moments in their lives, all the characters speak as though they are discussing the terms of their life insurance policies. There is a solemn emptiness to the tone of the film; even at the end, when Marion tries to make amends for past failings, she seems to be negotiating a contract, not saying "Let's start again." Such pompous droning seems designed to reflect the tone of the characters' lives; but the end result is monotonous and deadening, rather than being poetic and compelling.

The film does have a clever conceit: the always marvelous Gena Rowlands plays Marion Post, a professor of philosophy, who sublets an apartment to serve as an office where she can write her latest book. A quirk in the ventilation system allows her to inadvertently eavesdrop on the conversations going on next door. The next apartment is the office of a psychiatrist, who counts among his patients a young pregnant woman, played by Mia Farrow. The young woman discusses at length her sorrowful life and suicidal impulses. Because she identifies with the younger woman's feelings of loneliness and alienation, Marion becomes obsessed with eavesdropping on the sessions and uses the situation as a springboard for reevaluating her own life.

It is significant that just as Allen tells the story from a sterile distance, Marion reviews her life only indirectly, though voice-overs, flashbacks, dreams and even symbolic stage productions. Even her psychoanalysis is conducted through a surrogate, Farrow's character, who is rather obviously named Hope. Much of the interaction with other characters occurs in Marion's mind. And rather predictably, Marion's journey of self discovery is, well, rather predictable. She discovers -- as protagonists in this sort of film always discover -- that her successful career and her well-ordered life are a facade hiding her empty relationships and assorted personal failures. Her life of satisfied accomplishment is meaningless and the trust, love and respect she believes she shares with others are delusions. It's like IT'S A WONDERFUL LIFE in reverse: Just as the angel Clarence acts as George Bailey's conscience to show him how valuable his life has been, Hope acts as Marion's conscience to reveal how empty her life as become.

ANOTHER WOMAN has a counterpart in Allen's 2003 film, ANYTHING ELSE; another film with an obvious doppelganger. The former is about a woman who encounters her younger alter ego and reevaluates her past choices, while the latter is about a young man whose encounters with his older alter ego (played by Woody Allen) effects the choices that will shape his future. The same basic story is approached from opposite directions.

It's dangerous to speculate, but it seems that Allen made ANOTHER WOMAN during a time in his life when he was hugely admired for his accomplishments and he was deeply involved in a relationship with Mia Farrow and her extended family. Certainly Farrow's playing a pregnant woman and Marion's second thoughts over placing career over personal relationships seem to suggest a parallel. By contrast, ANYTHING ELSE, made a decade and a half later, finds Allen's character playing a mentor at a time when he is apparently happily married to a much younger woman, and where his status as a filmmaker is more iconic than in vogue. As such, his surrogate changes from being the central figure to the sadder but wiser voice of experience.

Both films are steeped in regret, but make an effort to end in an upbeat fashion. But while ANOTHER WOMAN is an accomplished, polished work striving for a cool perfection, it is not persuasive in its attempt to inspire us with optimism. ANYTHING ELSE is rambling and unfocused and, well, sloppy, but its optimism is honest and funny. ANOTHER WOMAN is about getting another chance, but there is no reason to believe that anything will really change in Marion's tight, introspective little life.

- How long is Another Woman?Powered by Alexa

Details

Box office

- Budget

- $10,000,000 (estimated)

- Gross US & Canada

- $1,562,749

- Opening weekend US & Canada

- $75,196

- Oct 16, 1988

- Gross worldwide

- $1,562,749

Contribute to this page

Suggest an edit or add missing content