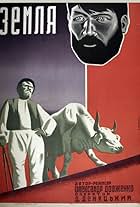

An abstract depiction of the childhood of Aleksandr Dovzhenko.An abstract depiction of the childhood of Aleksandr Dovzhenko.An abstract depiction of the childhood of Aleksandr Dovzhenko.

Vladimir Goncharov

- Sashko

- (as Vova Goncharov)

Evgeniy Bondarenko

- Mykola - otets

- (as Ye. Bondarenko)

Zinaida Kirienko

- Odarka - maty

- (as Z. Kiriyenko)

Boris Andreyev

- Platon Poltorak

- (as B. Andreyev)

Ivan Pereverzev

- Nachalnik stroitelstva

- (as I. Pereverzev)

Grigoriy Zaslavets

- Savka

- (as G. Zaslavets)

Anatoli Yushko

- Drobot

- (as A. Yushko)

Vyacheslav Voronin

- Boris Troyanda

- (as V. Voronin)

Ivan Zhevago

- otets Kirill

- (as I. Zhevago)

Boris Yurchenko

- Dyak Luka

- (as B. Yurchenko)

Vladimir Perepelyuk

- Bandurist

- (as V. Perepelyuk)

Mikhail Gladysh

- Makar - zhandarm

- (as M. Gladysh)

- Director

- Writer

- All cast & crew

- Production, box office & more at IMDbPro

Storyline

Did you know

- TriviaHailed by Jean-Luc Godard as the best movie of 1965.

- ConnectionsFeatured in Women Make Film: A New Road Movie Through Cinema (2018)

Featured review

A memoir film-Solntseva's adaptation of her late husband Aleksandr Dovzhenko's autobiographical sketch for a personal film-the film, as befits its title, is more a kind of eruptive ode to place which, like the river itself, flows, eddies, occasionally bursts its banks; in which the rhapsodic exceeding of linearity, memories as they come to mind, sensations, sketches, truncates and transcends narrow biographical cliches. The film takes place in three time frames, three worlds, all centred around the river. There's the murky, smoke-and-fire-filled landscapes of wartime Ukraine, in which even daytime seems to be nocturnally shadowed, and in which night's own shadows are relentlessly punctured and punctuated, not by stars or night birds, but by explosions, and a haranguing monologue by the ferryman who accuse the fleeing Ukranian soldiers of abandoning their land, of capitulation to the Nazis. Then, brought to life from Aleksander's memories, deep in the heart of wartime, those sequences from which the film is most remembered-the ecstatic memories of a childhood marked by poverty, by a relentless engagement-half battle, half love affair-with the natural forces of the river, of the tending of the harvest, the crop-sunflowers, apples, blossoms-rendered in a symphony of scythes, flowers, floods. Finally, an epilogue set in a giant dam-building project, poised, like the film as a whole, between a rapturous paean to natural forces-particular that of the titular review, filmed in glowing sunsets and hazy long shots-and a techno-futurist proclamation of taming those forces (with a somewhat clunky definition of dialectics-as 'the transition from past to future'-shoehorned into a conversation between engineers). Across these three periods, Alekander at times seems to be, as he claims at one point, an artist, at others a soldier, at others an inventor or engineer. All three, it's suggested, are roles in which the imagination is central, in which the sometimes ruthless demands of practicality must never overwhelm the demands and desires of memory, of relationship to place, of an imbricated geological understanding based, not on domination, but on a kind of give and take. The film is explicitly both constructed on a (literal) journey from infancy to maturity, mapped onto Ukraine's progress towards an enlightened Soviet future named as Communism; yet implicitly, deep within its form, it insists that temporality, within this poetic sensibility, is more porous. Breaking off from his wartime memoir-writing in self-critical awareness, Aleksander notes the presence of the three editors inside his head, one behind his left ear, one behind his right, one in front, and wonders if his recollection of seeing a lion on the riverbank during a night-time boat ride was mere fantasy, and that writing on lions diverts from the realism he seeks to convey; yet the mangy horses his family owned cause too much shame to be suitable subjects, and in any case, a lion did escape from the circus one year, heading for the river, Aleksander supposes, because it was fed up of the eternal round of exploitation in the circus. While Aleksander's chosen mode of expression lies in words, and despite the ever-present voiceover-and the insistent over-production of meaning in the bombastic musical score-the film's most memorable moments are visual, in excess of a single or singular message (and thus more properly dialectical than any clunky Stalinist reduction of philosophical method to ideological trope). The infant Aleksandr rushing through fields of giant sunflowers, blossoms, shaking apples from tree, having visions of lions, visions of talking horses bemoaning their exploitation by the humans who take out their own frustrations on them, the camera moving and diving on a child's or a god's eye-level, sweeps of landscape, details rushing forward to meet the camera as an active agent of perception motivated by the excitements of the moment and the longer sweep of history. The film is set up as one about teaching and learning-as Godard said in 1965, "(this is a film) about which I don't know what to say critically, which give me the feeling of having a lot to learn"-yet what it teaches, and what we might learn from it, emerges as much from the relentless horizontal spread, the bursts of brighter-than-life colour or murkier-than-life night, the exaggerations, distortions and reflections that, presented visually, can't be captured in verbal argument. As well as a hymn to the river, one might say that Solntseva's film is a hymn to film itself.

Details

- Release date

- Country of origin

- Language

- Also known as

- The Enchanted Desna

- Production company

- See more company credits at IMDbPro

- Runtime1 hour 21 minutes

- Color

- Sound mix

- Aspect ratio

- 2.20 : 1

Contribute to this page

Suggest an edit or add missing content