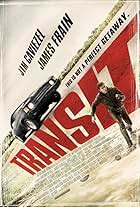

A man attempting to escape occupied France falls in love with the wife of a dead author whose identity he has assumed.A man attempting to escape occupied France falls in love with the wife of a dead author whose identity he has assumed.A man attempting to escape occupied France falls in love with the wife of a dead author whose identity he has assumed.

- Awards

- 9 wins & 26 nominations

- Director

- Writers

- All cast & crew

- Production, box office & more at IMDbPro

Storyline

Did you know

- TriviaAccording to Christian Petzold, this movie is the last chapter of his trilogy called "Love in Times of Oppressive Systems". The trilogy also includes Barbara (2012) and Phoenix (2014).

- Quotes

Georg: A man had died. He was to register in hell. He waited in front of a large door. He waited a day, two. He waited weeks. Months. Then years. Finally a man walked past him. The man waiting addressed him: Perhaps you can help me, I'm supposed to register in hell. The other man looks him up and down, says: But sir, this here is hell.

- ConnectionsFollows Barbara (2012)

- SoundtracksKarneval der Tiere - Der Kuckuck

Composed by Camille Saint-Saëns

Performed by Franz Rogowski (uncredited)

(c) copyright control

Recorded by Stefan Will

Featured review

Transit is based on Anna Seghers's 1942 novel of the same name about a German concentration camp survivor seeking passage from Vichy Marseilles to North Africa, as the Nazis move ever closer to the city. However, rather than a 1:1 adaptation, the film is built upon a fascinating structural conceit - although it tells the same story as Segher's novel, it is set in the here and now. At least, some elements are set in the here and now. In fact, only part of the film's milieu is modern. So, although such things as cars, ships, weaponry, and police uniforms are all contemporary, there are no mobile phones, no computers, people still use typewriters and send letters, and the clothes worn by the characters are the same as would have been worn at the time. In essence, this means that the film is set neither entirely in 1942 nor entirely in 2019, but in a strange kind of temporal halfway-house, borrowing elements from each. There's a fairly obvious reason that writer/director Christian Petzold employs this strategy, and it has to be said, it works exceptionally well, with the film's thematic focus symbiotically intertwined with its aesthetic to a highly unusual degree. Petzold doesn't so much suggest that history is repeating itself, as postulate that there's no difference between then and now. Unfortunately, aside from this daring aesthetic gambit, not much else worked for me, with the plot somnolent and the characters void of any relatable emotion.

The film tells the story of Georg (Franz Rogowski) a young man on the run from the "fascists". In Paris, he's entrusted with delivering some papers to George Weidel, a communist author currently in the city. However, when Georg goes to Weidel's hotel room, he finds the writer has committed suicide. Taking an unpublished manuscript, two letters from Weidel to his wife Marie, and Weidel's transit visa for passage to Mexico, Georg stows away on a train heading for Marseilles, one of the few European ports not yet under fascist control. Upon arriving, Georg visits the wife of a friend who died, Melissa (Maryam Zaree), to give her the bad news. However, she's deaf, and he has to explain the death through her young son, Driss (Lilien Batman), with whom he quickly forms a bond. Meanwhile, when he goes to the Mexican consulate to return Weidel's belongings, he is mistaken for Weidel himself, and he realises he has a chance to escape Europe, with Weidel booked on a ship sailing in a few days. As Georg awaits passage, he has several encounters with a mysterious woman, who, it is soon revealed is none other than Marie Weidel (Paula Beer), who is waiting for word from her husband. Not telling her that Weidel is dead, Georg finds himself falling for her.

Shot on location in Paris and Marseilles, everything from street signs to cars (including a few electric ones) to the front of buildings is modern, whilst Hans Fromm's crisp digital photography hasn't been aged in any way whatsoever. In terms of cultural signifiers, Petzold keeps it vague, although there is a reference to Dawn of the Dead (1978), with the closing credits featuring "Road to Nowhere" (1982). However, for everything that seems to locate the film in the 21st century, there's something to locate it in the 1940s, whether it be the absence of mobile phones, computers, and the internet, or the ubiquity of typewriters and letters. Along the same lines, Petzold keeps the politics generalised, with no mention of Nazis, concentration camps, or the Holocaust. Instead, the film makes reference to archetypal "fascists", never-defined "camps", and systemic "cleansing".

The combination of liminal elements of modernity and period-specific history sets up a temporal/cognitive dissonance which forces the audience to move beyond the abstract notion that what once happened could happen again. Instead, we are made to recognise that the difference between past and present is a semantic distinction only, and that that which once happened never really stopped happening. Indeed, given the resurgence of Neo-Fascism across Europe, built primarily on irrational xenophobic fears of the Other in the form of immigration, the refugee crisis is as bad today as it ever was in the 40s. The temporal dislocation also suggests both the specificity and the universality of the refugee experience - every refugee is fundamentally unique, but so too is the experience the same.

The other important aesthetic choice is the use of a very unusual voiceover narration. Introduced out of the blue as Georg begins reading Weidel's manuscript at around the 20-minute mark, there's no initial indication as to the narrator's identity or when the narration is taking place. Additionally, the narrator is unreliable, as on occasion he describes something differently to how we see it. The narration also "interacts" with the dialogue at one point - in a scene between Georg and Marie, their dialogue alternates with the VO; they get one part of a sentence and the VO completes it, or vice versa.

However, although I really liked the temporal dissonance, the experimental VO didn't work nearly as well, serving primarily to pull you out of the film as you try to answer a myriad of questions - where and when is the voice is coming from; what is its relationship to the narrative; are we hearing a character speak or someone outside the fabula; how can the narrator have access to Georg's innermost thoughts at some points but not at others; why is the voice able to accurately describe things not seen by Georg, but often inaccurately describe things which are; why does the narration seem to be ahead of the narrative at some points, and behind it at others; what is the purpose of the pseudo-break of the fourth wall by having the VO alternate with dialogue? I don't have answers to all of these questions, but I think the point of the destabilising/defamiliarising narration is to reinforce the experience of being a refugee, which is a mass of stories within stories and fragments that often contradict one another.

The film has more problems than just the VO, however. To suggest the disenfranchised nature of what it is to be a refugee, Petzold depicts Georg as a non-person; he has very little agency and is instead someone to whom things happen. In short, he's passive, less a protagonist than a witness. Passive characters can work extremely well in the right circumstances (think of Chance Gardner (Peter Sellers) in Being There (1979), or the most famous example, Hamlet), but here, passivity combines with a dearth of backstory and character development, whilst Rogowski plays the part without a hint of interiority. Easily the most successful scenes in the film are those showing his friendship with Driss because they're the only moments where he seems like a person rather than a narrative construct, they're the only parts of the film that ring emotionally true.

This friendship, however, is secondary to the love story between Georg and Marie. Except that it isn't a love story; there's no emotional realism to it whatsoever. I understand what Petzold is going for here. He doesn't want a Hollywood love story of fireworks and poetic monologues, he wants to show that the war and their status as refugees has stripped them of their identities, and they are now effectively shells. However, this in no way necessitates such a badly written relationship void of emotional truth.

What Petzold is trying to do in his characterisation of Georg is clear enough; as an archetypal refugee, Georg can't be seen to have much control over his affairs, and his time in Marseille must be static, an existence in-between more fully realised states. Petzold uses this to try to imply that to be divested of one's country is to be divested of one's identity. However, the extent of his passivity renders him completely unrealistic - he's not a person, he's a robot.

Tied to this is a lack of forward narrative momentum. Again, I understand that Petzold is trying to stay true to the experience, that the life of a refugee must necessarily involve a lot of waiting, repetition, and frustration. But again, it's the extent to which the film goes to suggest this. Yes, inertia is part of the theme insofar as the film depicts people suffering from crippling inertia, but it doesn't necessarily follow that the film needs to be so unrelentingly dull.

Easily the most egregious problem is one that arises from a combination of these issues - it's impossible to care about any of the characters. Think of films as varied as The Boat Is Full (1981), Le Havre (2011), or The Other Side of Hope (2017). All depict refugees, and all ring true emotionally, because they're populated by characters about whom we come to care. This is precisely what Transit is lacking. There is no pathos, with none of the characters coming across as anything but a cipher, a representative archetype onto which Petzold can project his thematic concerns. With little in the way of psychological verisimilitude or interiority, they simply never come alive as real people.

An intellectual film rather than an emotional one, Transit is cold and distant. And this coldness and distance has a cumulative effect, with the film eventually outlasting my patience. The temporal dissonance works extremely well, but it's really all the film has going for it. Petzold says some interesting things regarding the experience of refugees in the 21st century vis-à-vis refugees of World War II, and the mirror he holds up to our society isn't especially flattering. If only we could care about someone on screen. Anyone.

The film tells the story of Georg (Franz Rogowski) a young man on the run from the "fascists". In Paris, he's entrusted with delivering some papers to George Weidel, a communist author currently in the city. However, when Georg goes to Weidel's hotel room, he finds the writer has committed suicide. Taking an unpublished manuscript, two letters from Weidel to his wife Marie, and Weidel's transit visa for passage to Mexico, Georg stows away on a train heading for Marseilles, one of the few European ports not yet under fascist control. Upon arriving, Georg visits the wife of a friend who died, Melissa (Maryam Zaree), to give her the bad news. However, she's deaf, and he has to explain the death through her young son, Driss (Lilien Batman), with whom he quickly forms a bond. Meanwhile, when he goes to the Mexican consulate to return Weidel's belongings, he is mistaken for Weidel himself, and he realises he has a chance to escape Europe, with Weidel booked on a ship sailing in a few days. As Georg awaits passage, he has several encounters with a mysterious woman, who, it is soon revealed is none other than Marie Weidel (Paula Beer), who is waiting for word from her husband. Not telling her that Weidel is dead, Georg finds himself falling for her.

Shot on location in Paris and Marseilles, everything from street signs to cars (including a few electric ones) to the front of buildings is modern, whilst Hans Fromm's crisp digital photography hasn't been aged in any way whatsoever. In terms of cultural signifiers, Petzold keeps it vague, although there is a reference to Dawn of the Dead (1978), with the closing credits featuring "Road to Nowhere" (1982). However, for everything that seems to locate the film in the 21st century, there's something to locate it in the 1940s, whether it be the absence of mobile phones, computers, and the internet, or the ubiquity of typewriters and letters. Along the same lines, Petzold keeps the politics generalised, with no mention of Nazis, concentration camps, or the Holocaust. Instead, the film makes reference to archetypal "fascists", never-defined "camps", and systemic "cleansing".

The combination of liminal elements of modernity and period-specific history sets up a temporal/cognitive dissonance which forces the audience to move beyond the abstract notion that what once happened could happen again. Instead, we are made to recognise that the difference between past and present is a semantic distinction only, and that that which once happened never really stopped happening. Indeed, given the resurgence of Neo-Fascism across Europe, built primarily on irrational xenophobic fears of the Other in the form of immigration, the refugee crisis is as bad today as it ever was in the 40s. The temporal dislocation also suggests both the specificity and the universality of the refugee experience - every refugee is fundamentally unique, but so too is the experience the same.

The other important aesthetic choice is the use of a very unusual voiceover narration. Introduced out of the blue as Georg begins reading Weidel's manuscript at around the 20-minute mark, there's no initial indication as to the narrator's identity or when the narration is taking place. Additionally, the narrator is unreliable, as on occasion he describes something differently to how we see it. The narration also "interacts" with the dialogue at one point - in a scene between Georg and Marie, their dialogue alternates with the VO; they get one part of a sentence and the VO completes it, or vice versa.

However, although I really liked the temporal dissonance, the experimental VO didn't work nearly as well, serving primarily to pull you out of the film as you try to answer a myriad of questions - where and when is the voice is coming from; what is its relationship to the narrative; are we hearing a character speak or someone outside the fabula; how can the narrator have access to Georg's innermost thoughts at some points but not at others; why is the voice able to accurately describe things not seen by Georg, but often inaccurately describe things which are; why does the narration seem to be ahead of the narrative at some points, and behind it at others; what is the purpose of the pseudo-break of the fourth wall by having the VO alternate with dialogue? I don't have answers to all of these questions, but I think the point of the destabilising/defamiliarising narration is to reinforce the experience of being a refugee, which is a mass of stories within stories and fragments that often contradict one another.

The film has more problems than just the VO, however. To suggest the disenfranchised nature of what it is to be a refugee, Petzold depicts Georg as a non-person; he has very little agency and is instead someone to whom things happen. In short, he's passive, less a protagonist than a witness. Passive characters can work extremely well in the right circumstances (think of Chance Gardner (Peter Sellers) in Being There (1979), or the most famous example, Hamlet), but here, passivity combines with a dearth of backstory and character development, whilst Rogowski plays the part without a hint of interiority. Easily the most successful scenes in the film are those showing his friendship with Driss because they're the only moments where he seems like a person rather than a narrative construct, they're the only parts of the film that ring emotionally true.

This friendship, however, is secondary to the love story between Georg and Marie. Except that it isn't a love story; there's no emotional realism to it whatsoever. I understand what Petzold is going for here. He doesn't want a Hollywood love story of fireworks and poetic monologues, he wants to show that the war and their status as refugees has stripped them of their identities, and they are now effectively shells. However, this in no way necessitates such a badly written relationship void of emotional truth.

What Petzold is trying to do in his characterisation of Georg is clear enough; as an archetypal refugee, Georg can't be seen to have much control over his affairs, and his time in Marseille must be static, an existence in-between more fully realised states. Petzold uses this to try to imply that to be divested of one's country is to be divested of one's identity. However, the extent of his passivity renders him completely unrealistic - he's not a person, he's a robot.

Tied to this is a lack of forward narrative momentum. Again, I understand that Petzold is trying to stay true to the experience, that the life of a refugee must necessarily involve a lot of waiting, repetition, and frustration. But again, it's the extent to which the film goes to suggest this. Yes, inertia is part of the theme insofar as the film depicts people suffering from crippling inertia, but it doesn't necessarily follow that the film needs to be so unrelentingly dull.

Easily the most egregious problem is one that arises from a combination of these issues - it's impossible to care about any of the characters. Think of films as varied as The Boat Is Full (1981), Le Havre (2011), or The Other Side of Hope (2017). All depict refugees, and all ring true emotionally, because they're populated by characters about whom we come to care. This is precisely what Transit is lacking. There is no pathos, with none of the characters coming across as anything but a cipher, a representative archetype onto which Petzold can project his thematic concerns. With little in the way of psychological verisimilitude or interiority, they simply never come alive as real people.

An intellectual film rather than an emotional one, Transit is cold and distant. And this coldness and distance has a cumulative effect, with the film eventually outlasting my patience. The temporal dissonance works extremely well, but it's really all the film has going for it. Petzold says some interesting things regarding the experience of refugees in the 21st century vis-à-vis refugees of World War II, and the mirror he holds up to our society isn't especially flattering. If only we could care about someone on screen. Anyone.

- How long is Transit?Powered by Alexa

Details

- Release date

- Countries of origin

- Official sites

- Languages

- Also known as

- Транзит

- Filming locations

- Production companies

- See more company credits at IMDbPro

Box office

- Gross US & Canada

- $815,290

- Opening weekend US & Canada

- $31,931

- Mar 3, 2019

- Gross worldwide

- $1,012,747

- Runtime1 hour 41 minutes

- Color

- Aspect ratio

- 2.39 : 1

Contribute to this page

Suggest an edit or add missing content