Change Your Image

Benedict_Cumberbatch

Lists

An error has ocurred. Please try again Aluísio's 5 Favorite Female Performances

Aluísio's 5 Favorite Female Performances

Reviews

Once Upon a Time in... Hollywood (2019)

On Quentin Tarantino's "Revenge Fantasy" extravaganza

"Once Upon a Time in... Hollywood" is Quentin Tarantino's 9th feature film (his penultimate, if he really decides to retire after his 10th film, as he's said before). From countless references to a myriad of films (pastiche or homage, depending on how you look at it) to excessive shots of female feet and an ultraviolent climax, it seems like just your typical Tarantino film. It is. But that's not necessarily a good thing.

The only Tarantino film I truly love is Pulp Fiction, though I find things to admire in all of them. I've always admired him more as a fellow film buff than as a filmmaker. He's undeniably talented, but extremely self-indulgent. Still, he's one of the few living filmmakers (Paul Thomas Anderson - a much superior filmmaker - is another one) that give us a true film event with every new work they release. They both make one film every few years, but while Anderson manages to always surprise us with the complexity and maturity of his work, Tarantino has been stuck with the simplistic "revenge fantasy" genre that he redefined with Inglourious Basterds (2009) and Django Unchained (2012).

I can't really express my disappointment with Once Upon a Time in... Hollywood without giving away spoilers. I won't bother with plot details and a synopsis, since I'm assuming you've seen the film if you're reading this. Just like Basterds ended with Nazis getting killed and Django gave slaves a chance to get revenge on their "masters," OUATIH ends with the Manson followers that murdered Sharon Tate and her friends in 1969... getting killed by Brad Pitt and Leonardo DiCaprio. In Tarantino's overlong, meandering and superficial "love letter" to Los Angeles and movies, Sharon Tate gets to live.

At the same time that I think we did NOT need another sensationalist movie depicting the Manson murders in graphic detail - and we all wish Tate had had a happy ending - I also find the "revenge fantasy" genre, when focusing on such tragic events (Holocaust, slavery, and the senseless murdering of innocents), to be simplistic and somewhat disrespectful. It is indeed easy to give the audience bloody satisfaction in seeing members of the Manson clan dying in a most grotesque way. It's also borderline idiotic. Tarantino can do whatever he wants with his films; as one should. But the 56 year-old filmmaker that he is now isn't any more mature than the 28 year-old that made Reservoir Dogs. His work is entertaining, and for some it's even cathartic; but it's too shallow for its own good. There's more to the art of filmmaking than rewriting history in straight lines, just like I believe there are superior films that Tarantino could give us if he tried a bit harder.

Love, Simon (2018)

The queer John Hughes teen comedy that Hollywood had never given us, thus far...

I needed something sweet, hopeful and romantic tonight, so I went to see Love, Simon. I loved every second of it.

Its simplicity is its biggest asset. Yes, it's a fairy tale, and obviously it doesn't represent the much harsher reality of many queer people (don't we all wish we were as privileged as Simon; that we had such loving, accepting parents and friends to come out!), but we have many other tragic films (some of them, outstanding) to reflect on that.

Love, Simon is simply the queer John Hughes feel-good movie that Hollywood had never given us, thus far. You'd have to search video stores for hidden (independent) gems like Beautiful Thing (1996) or Get Real (1998) in order to find feel-good gay-themed films. Nick Robinson is brilliant as Simon, and the soundtrack is delightful. It may have taken many years for Hollywood to give us such a treat, but hey, it's a start!

Thank you, Greg Berlanti. Those who are whining about your work can (and should) make their own movies. Representation doesn't come in one single package, so be the change you want to see. And go see this film in the theater. It's important, and above all, you will have a great time.

Love, Aluísio.

Song to Song (2017)

When a brilliant auteur goes down

First off, I must say I am not a Terrence Malick hater. On the contrary: I used to worship the man. I even took an entire course in film school dedicated to him, Orson Welles, and Stanley Kubrick. I think the 5 films Malick did in the first 38 years of his career ("Badlands," "Days of Heaven," "The Thin Red Line," "The New World," and "The Tree of Life") are all masterpieces. I even liked "To the Wonder," which was almost universally panned, even though it was clearly not in the same league as his previous films. After the acclaimed "The Tree of Life," Malick (now 73 years old) has been working on several projects in different stages of production. He filmed "Song to Song" immediately after "Knight of Cups" (released last year) back in 2012, and it's only being released now, as a 129-minute film, after almost five years of post-production and at least 8 editors to turn it into something remotely coherent (reportedly, the first cut was 8 hours long). Unfortunately, like "Knight of Cups," "Song to Song" feels like a parody of Malick's work: the extensive, mumbling voice-over narration by all the main characters (taken to the extreme), the stunning imagery of nature and high-end real estate, and gorgeous people literally walking in circles and acting cute (or mean) to one another. The very thin plot revolves, as you heard, around two intersecting love triangles set against the music scene in Austin, Texas. But music doesn't play a great part in this story, and it certainly could have elevated it.

As abstract as Malick's earlier films could be, they all had tangible, rich, philosophical and often universal themes. "Knight of Cups" and "Song to Song" are pure cinematic masturbation. Malick's trick is getting some of the biggest (and best-looking) film stars in the world, and his main actors (Rooney Mara, Ryan Gosling, Michael Fassbender, Natalie Portman) have faces that one can easily watch for hours. But not even these great stars can masquerade the emptiness of the film. Mara has the most screen time of them all, being the only true leading character here, while Cate Blanchett, Holly Hunter, Val Kilmer, and Berenice Marlohe are reduced to cameos. There's at least one painfully genuine moment, near the end, featuring Hunter's character, but it only lasts a few seconds; Malick's gaze isn't interested in her emotions. He'd rather show us, for the umpteenth time, Mara and Fassbender being flirty and sexy instead.

I am all about experimental cinema, but when you realize that this is the deepest sort of "experimental" project that Hollywood can put out (made by a revered auteur that movie stars almost pay to work with), you feel even more nostalgic for the daring collaborations between Tilda Swinton and the late Derek Jarman. I know people who deemed "Knight of Cups" a "masterpiece" and will probably say the same about "Song to Song." I try to be respectful of other people's opinions, but I really don't think we're seeing this film through the same lens. I still admire and respect Malick; I just liked his work more when he had something to say. Right now, I see him as someone who can afford to make gorgeous-looking home movies just for his pleasure, but he's a much more interesting artist when he expands his canvas into something we can truly care about.

Le bonheur (1965)

Deceptively simple, brilliantly subversive masterpiece from the legendary Agnes Varda

I have admired the work of the magnificent Agnes Varda ("Cleo from 5 to 7," "Vagabond," "The Gleaners and I," etc.) for years, yet I had never seen "Le Bonheur" (aka 'Happiness,' 1965) until now. It's one of her masterpieces, a perverse 79-minute fairy tale in reverse that is deceptively simple and brilliantly subversive.

Varda's inquisitive camera follows a happily married, attractive young couple with two kids (played by Jean-Claude Drouot, his actual wife Claire Drouot, and their own children Olivier and Sandrine). Everyone is perfectly happy and joyful, until François (Jean-Claude) meets another pretty blonde, Emilie (played by Marie-France Boyer), and decides that he loves her too. His wife Therese (Claire) is oblivious of the secret love affair, but it isn't long until François confesses to her that he's also in love with someone else. He hasn't fallen out of love with Therese; he has simply come to the conclusion that happiness works by addition, not subtraction. What happens next is what Varda explains as "taking apart the clichés" - and does she succeed at that!

I went into "Le Bonheur" expecting a clever, non-judgmental, very French take on polygamy and societal perceptions about love and happiness. What I got was a visually stunning (Varda's work on the color schemes and the cinematography by Claude Beausoleil and Jean Rabier are a feast for the eyes), morally ambiguous, and subtly perverse film that gets under your skin. In "Vagabond," which Varda directed twenty years after "Le Bonheur," one character says to the protagonist, Mona Bergeron (Sandrine Bonnaire): "You chose total freedom and you got total loneliness." François has his own idea of total freedom; a possessive, egotistical kind masquerading as loving and compassionate. Somehow, he defeats loneliness by choosing happiness over grief. The road to his happiness is another discussion altogether, and it's up for the viewer to decide whether or not there's any integrity behind his actions.

There's no doubt for me that Varda was a true visionary, and I'm so glad that, at 87, she's still working and sharing her brilliance with us. "Le Bonheur," in its apparent simplicity, is more complex and multi-layered than 90% of the films released in our day and age. 50 years after its initial release, it hasn't lost its panache, and still inspires new acolytes, like myself. The Criterion DVD edition, released a few years ago, has some great bonus features, such as recent interviews with Varda and the cast (including the Drouots, still married after 5 decades and claiming that the film helped their relationship!). 10/10.

Gravity (2013)

A technical wonder, a visual stunner

James Cameron has called Alfonso Cuaron's GRAVITY "the greatest space film ever made." I want to believe he means... "after 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY," although that should be a given, right? Nonetheless, Cuaron's follow-up to his brilliant CHILDREN OF MEN (2006) is another landmark in the sci-fi genre. The premise is simple, but the execution is what makes it a work of art. Dr. Ryan Stone (Sandra Bullock), a biomedical engineer from Illinois, and astronaut Matt Kowalski (George Clooney), must find a way to survive after an accident leaves them lost in space. The universal themes of survival and resistance (in space!) give room for Cuaron and his troupe to create some of the most beautiful visual effects you'll ever see.

As of 10/04/2013, I have seen only 3 films that have used 3D technology to really complement storytelling: Wim Wenders' PINA (2011), Martin Scorsese's HUGO (2011), and GRAVITY. However, even though GRAVITY is just as impressive technically as the aforementioned titles, it is my least favorite of the three because of its lead actors. Clooney is just being Clooney, and although this is the best Bullock has ever been, that hardly means much to me as I think she's a very bland actress. That soulless stare remains there, and I can't help but wonder what someone like Jessica Chastain could have done with this role. In Sandra's defense, I can also say she doesn't compromise the overall quality of the film too much, but she is my major complain about it (there's even an obvious "Oscar scene" written just for her).

GRAVITY may just fall short of masterpiece level, but it's still a fascinating film for its technical achievements. If the Academy does not recognize the work of cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki this time, they never will. Go see it in 3D as it's supposed to be seen, and enjoy the ride.

Don Jon (2013)

Solid directorial debut by the most likable American actor of his generation, Joseph Gordon-Levitt

"Don Jon" (formerly known as "Don Jon's Addiction") is the feature directorial debut of the talented and ridiculously charismatic Joseph Gordon-Levitt. He also wrote the script and plays the title character, a young man from New Jersey who's developed: a) an unhealthy addiction to porn; and b) such unrealistic expectations about sex and love (and sex) that not even a "10" like Barbara (a hilarious Scarlett Johansson, in what is easily her best work since "Vicky Cristina Barcelona") can satisfy him in real life.

"Don Jon" reminded me of a great, half-forgotten French film: Bertrand Blier's "Too Beautiful for You" (1989). In that film, a wealthy car dealer (Gerard Depardieu) who has everything – including a beautiful wife (Carole Bouquet) – falls for his plain, slightly overweight secretary (Josiane Balasko). "Don Jon" is also like Blier's film in the sense that Jon finds his "10," yet he's still unsatisfied. Both films are very different in tone, aesthetics, and geography, but they delicately touch in the realm of our own emotional misconceptions and immaturity. We live in a world where our ever-growing concern about self-image, and the belief that we must abide by unattainable beauty standards in order to find a decent match, have grown so out-of-hand that all we ever do is find obstacles to getting to know anyone who doesn't meet our own ridiculous requirements. We are always waiting for the illusory perfection. Levitt sharply illustrates this issue by way of porn addiction; it might be crude for some, but he manages not to fall into excessive vulgarity or toilet humor.

Also featuring the always wonderful Julianne Moore in an important role, plus Glenne Headly (I've missed her on the big screen), Tony Danza, and Brie Larson as Jon's parents and sister, respectively; "Don Jon" is worth the visit. Here's hoping for more JGL directorial efforts!

The Master (2012)

"I am a writer, a doctor, a nuclear physicist, a theoretical philosopher, but above all, I am a man, just like you"

Paul Thomas Anderson has grown as perhaps the greatest American auteur of his generation. At 42, this is his 6th film (following 1996's "Hard Eight", 1997's "Boogie Nights", 1999's "Magnolia" - my all-time favorite -, 2002's "Punch-Drunk Love", and 2007's "There Will Be Blood"). Like the late master Kubrick and the aging master Terrence Malick (who, coincidentally, just debuted his 6th film, "To the Wonder", at the latest Venice Film Festival where PTA won the Silver Lion for Best Director), he isn't the most prolific of filmmakers; but his perfectionist creations, cerebral yet strikingly cinematic and emotional, always leave an indelible mark (polarizing audiences but usually earning critical acclaim). "The Master" is no exception. Shot on 70mm film, it is not so much of an "outside" epic as you'd imagine - although every single image is stunning and perfectly composed (courtesy of cinematographer Mihai Malaimare Jr., who replaced Robert Elswit, Anderson's usual collaborator). It closely resembles "There Will Be Blood" in tone and content, but it stands on its own (Jonny Greenwood is once again responsible for the score).

Freddie Quell (Joaquin Phoenix) is a troubled and troubling drifter who becomes the right-hand man of Lancaster Dodd (actor extraordinaire Philip Seymour Hoffman), "the master" of a cult named The Cause in post-WWII America. Their strange, ambiguous relationship is the center of the film. "The Master" is a thought-provoking indictment of cult fanaticism and lies sold as religion, which has caused controversy and concern among Scientologists even before its release. By not mentioning real names, Anderson is capable of broadening the scope of his story and making it richer - and subtler - than a straightforward "Scientology flick" would have been. Like his previous films, there's more than meets the eye at a single viewing, and his attention to detail pays off (there's also a visual homage to Jonathan Demme's "Melvin and Howard", another favorite of Anderson's, in a motorcycle racing scene). Hoffman is as good as ever, and Amy Adams is highly effective (slowly depriving herself of cutesy mannerisms) as his wife. David Lynch's golden girl Laura Dern has a small role as well. But this is Joaquin Phoenix's hour, all the way. River Phoenix's younger brother has become a fascinating actor himself since Gus Van Sant's dark comedy "To Die For" (1995), and, after his much publicized "retirement from acting" and music career hoax in 2009, he managed to come back with a performance for the ages, which shall culminate in Oscar gold. As for Anderson, it is unsure whether the Academy will finally recognize him as he deserves. His films may still be too outlandish for the Academy's taste (he's announced his next project will be an adaptation of Thomas Pynchon's crime novel "Inherent Vice", a seemingly less ambitious project he hopes to make in less than five years). Regardless of Oscar numbers, we can rest assured that in a world where PTA gets to make such personal and original work and find his audience, there is still hope, and room, for intelligent filmmaking.

Senna (2010)

An Emotional Race

I was born and raised in Brazil. Although I'm not a big sports fan (not even soccer!), something I always get made fun of for, I remember vividly the 1st of May, 1994, the day Ayrton Senna died; even though I was only 6 years old. He was indeed a national hero, whether you cared for Formula One or not.

This is a solid, often fascinating documentary about a man's passion; in Senna's case, racing for the win. He won the F1 World Championship three times. His tragic death brings to mind the protagonists of Darren Aronofsky's two latest films: Randy "The Ram" (Mickey Rourke) in "The Wrestler" (2008), and Nina Sayers (an Oscar-winning Natalie Portman) in "Black Swan" (2010).

Still, I wouldn't call this a story about the search for "perfection." Senna's main appeal is its emotional journey. Brazil is a land of so many paradoxes, and so are its people. At the same time we can laugh at our own adversities (poverty, bad politics, crime history, etc.) by seeing the best of everything; Brazilians tend to inherently suffer from low self-esteem and disguised hopelessness which is only defeated at moments of national heroism, often in sports (Pele in soccer, for instance). I'm not saying Senna was a martyr of any sort. I believe he deserved to be called a national hero because of his talent, passion, and the way he entertained and made an entire nation proud. I never personally cared for Formula One, but I still remember the (sometimes annoying, but always nostalgic) friction noise of the racing cars we all saw on TV every Sunday morning. And the victory song that Brazilians will always associate with Senna. This film brings both elements (alongside some great footage) to introduce all these facets of Senna to a larger audience; and for others, like me, to celebrate the life of a true national hero.

Weekend (2011)

Perfect chemistry

I watched this film after a friend highly recommended it. The gay film festivals and critics' awards and nominations it's been getting are much deserved.

Russell (Tom Cullen), a young gay man in Nottingham, UK, picks up Glen (Chris New) at a nightclub. They have a one-night stand but realize they share much more than animal attraction. They spend a weekend together trying to figure out whether or not they can turn this into something "concrete".

"Weekend" is part of the 'brief encounter' subgenre I am a big fan of. It's a 'talkie' for excellence; if you love films like "Lost In Translation", "Before Sunrise" and "Before Sunset", you'll probably be smitten by this as well. A naturalistic approach to filmmaking - especially to such a dialogue-driven narrative like this - is very hard to pull off; but writer/director/editor Andrew Haigh knows how to create sparks. Special kudos go to the excellent protagonists, Tom Cullen and Chris New, whose on-screen chemistry is palpable, moving, and simply a pleasure to watch. This is a weekend you shouldn't sleep through.

Melancholia (2011)

Shiny happy people holding hands...

Lars von Trier is the only director with two films in my all-time top 10 list: "Breaking the Waves" (1996) and "Dogville" (2003). The same way "Dogville" remains the most psychologically disturbing film I've ever seen, Trier's "antichrist" (2009) is easily the most sickening cinematic experience I've ever had. Lars is polarizing even among his most ardent fans. I would never watch antichrist again, for it feels like it was made just for shock value - something I despise.

But the first true thing about Lars is this: you will love or hate his films, but you shall never be indifferent to them. And that to me is, in and of itself, an important quality. With his latest effort, "Melancholia", Trier more than redeems himself from "antichrist", making one of his greatest and most unforgettable films.

"Melancholia" is, like most of von Trier's work, divided into chapters; in this case, just two. The first half is "Justine" (Kirsten Dunst, magnificent), a beautiful but clinically depressed young woman on her wedding day with the sweet, gentle (perhaps, too gentle), and handsome Michael (Alexander Skarsgard). Trying her best to look happy ("I smile, I smile, and I smile"), Justine fails to please most around her, especially her sister Claire (Charlotte Gainsbourg, always fascinating) and her prick of a husband, John (Kiefer Sutherland); not to mention Michael himself. Other smaller but essential characters are Claire's son (Cameron Spurr), Justine and Claire's parents (the wonderfully bitter - as always - Charlotte Rampling, and John Hurt), Justine's boss (Stellan Skarsgard), his clueless nephew (Brady Corbet), and Trier's perennial friend and collaborator Udo Kier as the wedding planner (and the closest to a comic relief here).

The second half, "Claire", focuses on Gainsbourg's character's unraveling at the idea that Melancholia - "a planet hiding behind the sun" - might collide with Earth. As Claire and John - the shiny happy people we all strive to be - face despair, the morbidly sad Justine becomes more and more... peaceful. Von Trier has publicly declared his struggles with depression in the past, and he builds his film on the fascinating concept that depressives tend to feel more at home at times of intense distress (and possible catastrophe), while the "normal" people have a harder time facing or even considering tragedy. As someone who's been struggling with depression/bipolarity for years, I can personally relate to this.

Whether or not you're familiar with depression, "Melancholia" is a hypnotic piece of cinema - from the breathtaking images (by Portuguese cinematographer Manuel Alberto Claro), to the formidable performances, and the beautiful soundtrack (pieces from Wagner's opera "Tristan & Isolde" are the main theme). Von Trier's work, in my opinion, speaks for itself. He is, above all, a provocateur. He may fail miserably at his attempts at humor and be socially awkward, but I do not believe he is a bad guy - let alone a Nazi (regardless of his infamous remarks at this year's Cannes). One does not need to be a great man in order to be a great artist (in this case, filmmaker); but I do believe a sense of humanity must be inherent in the work of any great artist, and humanity is something I see dissected, questioned, and exquisitely represented in von Trier's oeuvre. And, if the world is indeed going to end in 2012 (which I don't believe, but you never know): as long as it ends the way von Trier predicts, I'm okay with it. See this film at all costs.

The Tree of Life (2011)

On Malick's "Tree of Life"

Last Wednesday, I watched Terrence Malick's fifth feature (in a career that began almost four decades ago), "The Tree of Life", for the second time. I saw it for the first time on opening night at a local theater this past summer, where I brought two friends (who brought two friends of theirs) with me, and we were all fascinated by it. There were definitely not more than twenty people attending the screening, and I saw at least three people walk out during the first half hour of its 139-minute runtime.

"Tree of Life" is, without a doubt, the most polarizing film of 2011. Visually and existentially speaking, it's a "literal" film. Its non-linear, absolutely unique and personal narrative (experimental and visually stunning, Malick's trademarks), however, left many viewers baffled. A movie theater owner in Connecticut even wrote an open "no refund policy" letter to warn patrons that this is an art film, and they would gain a lot from seeing it - but shouldn't get their money back if they decided not to watch it until the end.

Winner of the Palme d'Or at this year's Cannes Film Festival, I can't stop relating "The Tree of Life" to Lars von Trier's haunting, mesmerizing, and absolutely gorgeous meditation on depression and the end of the world, "Melancholia", which I also saw for the second time this past weekend and competed with Malick's film at Cannes. Although both films are different at the core topic, they are both existential, visually hypnotic pieces; somewhat experimental, and with extraordinary use of classical music. They're the two most unique cinematic experiences I've had all year so far; and I would argue, two masterworks for the ages.

Although I agree that only time can tell what films are the real classics, it is hard to deny the power of a film like "The Tree of Life", and its impact on the audience and critics. Made with an estimated $32 million budget, it made only $13 million at the American box-office. It is not a financial success by any means, yet people cannot stop talking about it. Now available on DVD, word keeps spreading out of what an astonishing film/what a massive piece of crap "The Tree of Life" is. There's no middle ground. People love it or hate it. But they're never indifferent to it (except those who walked out after twenty minutes, but I don't think they have the right to say anything about a film they didn't see; although it's arguable that this is not a sign of indifference but rather ignorance).

Malick is an auteur, a truly fascinating artist (like Von Trier, Kubrick, Bergman, Welles, Murnau, Altman, Fellini, Godard, and a few others) unafraid of taking risks, provoking and instigating us as an audience, and elevating the film experience to another level. "The Tree of Life" begins with a passage from the Book of Job: "Where were you when I laid the earth's foundation... while the morning stars sang together and all the sons of God shouted for joy?" In the Bible, Job is a man tested by God after Satan wagers Job only serves God because of His protection. When Job loses everything - family, wealth, health - he will rather curse himself than God. That was also a concept explored in the Coen Brothers' searing "A Serious Man" (2009). But "The Tree of Life" is not a black comedy, but rather a poetic testament, like Malick's films tend to be.

The main character, Jack O'Brien (played as a child by Hunter McCracken, and by Sean Penn as an adult), whose initials are, not by chance, J-O-B, is unhappy in spite of what it seems to be a very (financially) successful life. His childhood memories (growing up in 1950's Texas) are what we see for most of the film - paralleled with images of the foundation of the earth itself, from the black void to the damned dinosaurs. It's not hard to realize Jack is Malick's alter ego. Like Malick, Jack has two younger brothers, and one of them died at a fairly young age. Such loss was obviously devastating to the patriarch, a domineering Mr. O'Brien (Brad Pitt), and a loving Mrs. O'Brien (Jessica Chastain), a woman who used to believe in taking "the way of grace" through life - in other words, to never ignore traces of divine glory in the world. Except sometimes the way of nature brings such obstacles and tragedies our way that the scars won't easily heal - you want to die with the loved ones you've lost. Mr. and Mrs. O'Brien are the pillars of Jack's foundation; his brother's death and his father's severity, the crosses of a lifetime.

"The Tree of Life" provides more questions than answers. It is, after all, a meditation (and not an analysis) on the human condition. And there lies its richness. Groundbreaking as few films these days are, it's no wonder it's been compared to Kubrick's "2001: A Space Odyssey" (Malick even hired Douglas Trumbull of '2001' to design the film's visual effects - Life was Trumbull's first film since 1982's "Blade Runner"). Time will tell how this Tree will stand, but it has, right from its birth, some deep roots in film history.

J. Edgar (2011)

G-Men and Daffodils, Yesterday and Today

"Some people are so precious -- all this hoo-ha about bad role models and positive images! Of course gay people are murderers, bigamists, drug addicts and nasty people -- just as much as heterosexual people are all of these things. What it all boils down to is, we are all people, and we all have the same human desires. It just happens that some desires go this way and some desires go that way. It's sad when people are oppressed. But it's a question of rising above it. Personally, mentally and, if you have to, physically. " Jaye Davidson, famous for "The Crying Game" (1992), when inquired about the way homosexuals are perceived in the media.

Dustin Lance Black, the talented screenwriter/filmmaker who won a much deserved Academy Award for Gus Van Sant's "Milk" (2008), is responsible for another dense, non-linear, and utterly fascinating biopic of a controversial American figure, the first director of the FBI, J. Edgar Hoover (1895-1972).

Harvey Milk, the openly gay rights activist, was an American hero who deserved and needed to be rediscovered by the world, and the Black-Van Sant-Sean Penn teaming succeeded on that wonderfully. Hoover (Leonardo DiCaprio), on the other hand, was a more enigmatic - and definitely less honorable - figure who abused his power to gain fame and admiration (which made up for the emotional emptiness of his upbringing and whole life). Also, Hoover was, as many believe, a closeted homosexual who had a long-term relationship with his protégé, Clyde Tolson (played by Armie Hammer, "The Social Network"). That, obviously, is a big part of this story. But while "Milk" was about somebody who fought for civil rights, "J. Edgar" is a look into the darkness surrounding somebody who, repressed and unloved, used the politics of fear and abuse of power to make a name for himself. Black-Eastwood-DiCaprio manage to humanize Hoover's figure yet without ever trying to conceal or apologize for his despicable acts.

This brings me back to the Jaye Davidson quote with which I started this review. Gay people are no better or worse than heterosexual people. Harvey Milk was a hero, Edgar Hoover was a tragic - yet undeniably guilty - man who used his intellect for less than honorable purposes. This is a great film about a man who did some terrible things, on a large scale. In Black's own words, it's a cautionary tale. It's also a fine coverage of some important moments of American History in the 20th century. At heart, it's about choices. The young men and women out there are capable of becoming Edgars or Harveys, Anita Bryants or Rosa Parkses; it all depends on what they are taught to believe on: the value of power, or compassion.

Also starring Naomi Watts as Helen Gandy, Judi Dench as Anne-Marie Hoover, and Josh Lucas as Charles Lindbergh. 137 min.

Cidade de Deus (2002)

Cidade de Deus.

I watched "City of God" for the first time when it was initially released on DVD in Brazil (didn't get a chance to see it in theaters, but followed its gradual and glorious popularity, which started when it premiered at Cannes 2002, out of competition). Since it was officially released in the US only in 2003, it was eligible for the Oscars the following year (but no longer for Best Foreign Film, since it was the previous year's submission and it got snubbed), earning four nominations in categories no Brazilian film had ever been recognized before: director (Meirelles, co-director Lund didn't share the nod), adapted screenplay (Braulio Mantovani, based on Paulo Lins' book), editing (Daniel Rezende), and cinematography (Cesar Charlone). I saw it again in 2007, after living in the US for one year, and the impact was even bigger; just rewatched it last week, and now, more than ever, I agree with the instant classic status this hell of a film earned.

That does not mean I didn't like it the first time I saw it. I did - a lot. But, at the same time, it felt like deja vu - Brazilians like me grew up used to watching horrible stories like this on the news since we were kids, and although I was fortunate enough to have been raised in a small, peaceful town and never suffered from violence or extreme poverty as the people shown in the film did; Brazilians tend to grow callous of our country's status quo of violent third-world nation. Things are slowly changing for the better, but there's so much work that needs to be done; still, one never loses faith in their country's future.

The first paradox is the movie's title, which is the actual name of the largest 'favela' (slum) in Rio de Janeiro, a beautiful city most regarded internationally for its postcard-perfect beaches, the statue of Christ the Redeemer and the classic "Girl from Ipanema" tune. You would expect "City of God" would be a beautiful place, and although it's part of beautiful Rio, it is far from it. It is a place where hell breaks loose (has had since the 1960's, where the action starts), and the movie focuses on two boys, Buscape and Dadinho, who grow up to be, respectively, a photographer (earning his way out of the favela, not without a price), and one of the most feared drug dealers/assassins in the history of the town.

Another paradox is the frequent misconception of the movie's relevance. The non-linear narrative and stylish, frantic editing are reminiscent of Tarantino's 'Pulp Fiction', and the film was heralded as a "South American Goodfellas". These are fair comparisons, but they can also undermine the film's devastating impact and social relevance behind all the cinematic pyrotechnics involved. "City of God" may be considered a spectacle victim of the MTV fashion (which ranges from the quality of a "Trainspotting" to the stupidity of Michael Bay's extravaganzas), or a movie that uses such modern narrative conventions to tell a painfully brutal real story (that's been repeating itself for decades) in a palatable way. The polished visuals may remind you that you are seeing a movie; but the raw cruelty of seeing little kids having to choose whether to be shot in their hands or feet, just to cite one of the film's most scathing moments, won't leave your mind.

This is not just a film, but a story of chaos on earth, a human tragedy that shouldn't be ignored or forgotten. Some may see "City of God" as an 'action movie', but they will be missing its real meaning, and the power that a good film can have to make us see beyond our general scope of reality.

Scream 4 (2011)

Wes Craven, Kevin Williamson and Neve Campbell still make the difference - a fun, nostalgic, and witty sequel that doesn't f*** with the original

I'm 23 years old. 12 years ago, I watched the original "Scream" (1996) and it was the first horror movie I enjoyed. It was a landmark in the puberty years of many movie-buffs-to-be who grew up in the late 1990's (good times!). SCREAM 2 & 3 were released in 1997 and 2000, respectively, and although entertaining, didn't hold a candle to the original (which is fine, most sequels don't). "Scream 3", in particular, lacked Kevin Williamson behind the script, and not even Wes Craven could turn what Ehren Kruger wrote into gold (meaning, a good flick; it did make a lot of money, though, and Parker Posey made it hilarious at moments).

So, eleven years later, a new SCREAM movie comes out, reuniting the original director, writer and the three survivors of the franchise, heroine Sidney Prescott (my first movie crush, Neve Campbell, still naturally beautiful and always a competent actress), Dewey (David Arquette) and Gale (Courteney Cox). Die hard fans, like me, have been waiting for this for a decade, and it paid off. Actually, it works so well because it was made 11 years after the last installment. The movie is far from perfect, obviously, but stands as the best of the sequels; "Scream 2" was above the average but came way too soon, and the third one was a wasted opportunity.

The tongue-in-cheek humor works for the most part, and Williamson knows how to parody a trend that he (re)created himself, including the ridiculousness of torture porn from the likes of SAW and its annual sequels - "movies with no character development, in which you don't care who lives or dies". That is the strongest link in this franchise: we've come to care about Sidney, Dewey and Gale, making the SCREAM movies work equally as slashers and satires. Whether or not SCREAM 5 & 6 will be made, it all depends on how much money this will make; I'm satisfied with this 4th chapter, although I won't deny I will still see another one if Craven, Williamson, and Campbell are involved. That said, it was a nostalgic flick that made me feel like I'm a preteen again. It may be a "new generation with new rules", but the iPhone generation oughtta know: "The first rule of remakes: you don't f*** with the original". Bravo, Sidney!

La bête humaine (1938)

The Human Beast

"La Bete Humaine", also known as 'The Human Beast' or 'Judas Was a Woman', is the third Jean Renoir film I have had the privilege to watch, a couple years after 'The Grand Illusion' (1937, possibly his most celebrated work) and 'The Rules of the Game' (1939, probably my favorite of the bunch).

The 1930's was considered by many to be Renoir's most creative period. 'The Grand Illusion' was the poignant story of two officers of distinct social backgrounds captured during World War I, while 'The Rules of the Game' was a sharp analysis of the French bourgeoisie and their servants at a château during the onset of World War II (a premise that would inspire Robert Altman to craft his beautiful 'Gosford Park', sixty-two years later). 'La Bete Humaine', based on Emile Zola's novel of the same name, is a more intimate work; not an ensemble film, but a fascinating story of love and crime that preceded the classic film noir.

Jean Gabin, one of the greatest of all French actors, plays Jacques Lantier, a train engineer who falls for the deceitful Severine (Simone Simon), the young wife of Roubaud (Fernand Ledoux), his co-worker. As Roubaud finds out that Severine has had a long-term affair with her wealthy godfather, Grandmorin, they both plan to kill him on a train journey. An innocent passenger is convicted for the murder instead, while Lantier, the only witness to the crime, remains quiet. He begins an affair with Severine, who then tries to persuade him to kill Roubaud. Lantier, however, suffers from hereditary mental instability and unpredictable violent fits, especially when under the influence of alcohol, and things might just not go the way the femme fatale has planned.

The locomotive is one of the main characters in the film. It serves as Lantier's home, workplace, and only refuge, and also where his tragic bond with Severine begins. It's more than a visual prop and a metaphor to his state of mind/life, since it comes alive on the screen in a most unusual way - the splendid cinematography by Curt Courant only adds to it. The original novel (part of a large series by Zola, which includes 'Germinal', also adapted to the big screen) was supposed to take place in the late 1800's, but the film adaptation is a clear product of its time, and, just as Renoir's war-themed stories ('The Grand Illusion' and 'The Rules of the Game'), it represents and foreshadows a dark period for a nation's whole history and humanity (World War II was indeed about to begin).

At once, a great early film noir of sorts and a profound character study about human qualities, flaws and needs, 'La Bete Humaine' is a beautiful piece of work. Fritz Lang would remake the story as 'Human Desire' (1954), starring Glenn Ford, Gloria Grahame and Broderick Crawford; a film I have yet to see. Still, I find it hard to believe it could surpass Renoir's vision - and I consider myself a Lang fan.

Le corbeau (1943)

Here comes The Raven

I was familiar with two of Henri-Georges Clouzot's (1907-1977) most celebrated films, 'The Wages of Fear' (1953), and 'Les Diaboliques' (1955), both of which I love. Only recently I learned about and watched the controversial and equally brilliant 'Le Corbeau' (1943, aka 'The Raven').

'Le Corbeau' is an unusual film; still unsettling and thought-provoking almost seventy years after its initial release. The plot, loosely based on a true story that happened two decades earlier, basically revolves around a series of poison-pen letters written by a mysterious person who signs as 'The Raven'. The letters spread rumors in a small French village, turning the inhabitants against one another, and focus on accusing the local doctor, Remy Germain (Pierre Fresnay), of having an affair and practicing illegal abortions. Releasing such a film (produced by a German company, Continental Films) in France during World War II proved to be quite dangerous, as it was banned after the Liberation (1944), and had its director and some of its stars judged for collaboration with the Germans/banned from their profession.

By watching this film for the first time, even now in 2011, one can easily see why it caused such a stir during the War. 'Le Corbeau' is allegorical cinema at its finest; although the symbolism present in the apparently simple plot can be interpreted in a myriad of ways - there lies the richness of great art - it is not hard to see the brilliant analysis of a community's paranoia in times of war. In a way, it reminds me of Don Siegel's classic 'Invasion of the Body Snatchers' (1956) and its indictment of McCarthyism, behind the apparently cheesy sci-fi facade.

Films, like any other art form (when/whether they achieve the level of art or not is another story altogether), are products of their time. Some age well, others don't; yet they remain a relevant document of the period they represent. 'Le Corbeau' not only has aged very well, but still holds the intellectual punch it did 68 years ago. Today's relative lack of censorship has killed subtlety in film for the most part. Modern satires often rely on shock value, visual and mental masturbation in order to provoke the audience. One of the most memorable scenes in 'Le Corbeau', for me, is the one in which a little girl desperately states her wish to die after finding out (through a poison-pen letter) that she is an illegitimate child. It strikes me as a poignant and yet so disturbingly real scene that you rarely see in films today (we're not talking the seductive prose and visual feast of 'The Virgin Suicides', but a dead serious representation of a child's desperation among adults going insane); let alone back in 1943. 'Le Corbeau' was and remains a brave film; a truly original, intriguing, timeless piece of cinema, and I'm glad I've finally discovered it. Regardless of the viewer's approach - as a mystery, a satire, a peculiar melodrama - it is sure to make one think.

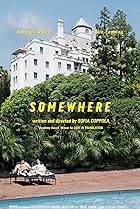

Somewhere (2010)

Everything that worked out beautifully in "Lost In Translation"...

...makes "Somewhere" an utterly forgettable, self-indulgent (in the worst sense of the term) waste of celluloid. I gotta say, first of all, I have immense respect and admiration for Sofia Coppola. The girl who showed the world she couldn't act in "The Godfather III" had a decade to find herself and prove everybody she was a sensitive, talented writer-director with 1999's "The Virgin Suicides". "Lost In Translation" (2003), which gave her the Oscar for best original screenplay (and a nomination for best director - the third female and first American woman to ever be nominated in that category), is my #3 favourite film of all time. I can watch it over and over and every frame of it can make me appreciate the beauty of life, film, human connections, and music, more. Sounds corny, doesn't it? Well, but it's true.

Sofia's follow-up to LiT, 2006's ostracized "Marie Antoinette", was, yes, sort of shallow, but I have to admit that eye candy and great music alone make it a delicious piece of cake for me. The same can't be said about her latest, "Somewhere", which won the Golden Lion for Best Film at Venice 2010 (a blasphemy, specially considering titles like "Black Swan" and "Balada Triste" were in competition). It follows a bored, kind of good-looking, shallow and womanizing movie star, Johnny Marco (Stephen Dorff) who (surprise) goes through an emotional transformation after spending some time with his 11 year-old daughter (product of a failed marriage), Cleo (Elle Fanning, a more natural actress than her older sister Dakota). We already knew that Sofia is fascinated by the ennui of the rich; but what made Bob Harris and Charlotte such wonderful characters in "Lost In Translation" was their humanity (and the chemistry between their fine performers, Bill Murray and Scarlett Johansson). Johnny Marco is not 1/5 as interesting as those two. Not every main character needs to be likable for a film to work for me, at all - I love character studies, no matter how conflicted ("The Piano Teacher") or pleasant ("Happy-Go-Lucky") the protagonist might be.

However, Marco is not someone interesting enough to spend 97 minutes with, and although Cleo seems to be a nice enough girl, she can't carry a whole film on her shoulders. They don't even share the historical curiosity of a figure like Marie Antoinette and her colorful ways. Marco is just shallow. Filthy rich. Bored. And boring. It's hard to feel bad for him, or even compelled to follow what he might become (the open ending, in that sense, is not a quality, since the movie ends when it could possibly become somewhat interesting). The soundtrack was nice enough (not memorable like those of her previous work), the cinematography is pretty enough (by Harris Savides, and not Lance Acord, this time around), but this is no 'Lost in Translation Redux', or even a film I would want to see again. It's a shame, but I am still curious to see what you do next, Sofia. I know you have it in you to amaze us! Verdict: 3/10.

P.S.: Quentin Tarantino, Sofia's ex-boyfriend who awarded "Somewhere" the Golden Lion as president of the jury at Venice last September, later wouldn't even name it one of his top 20 movies of the year (yet, he lists abominations such as "Jackass 3D", "Knight and Day"...). That can prove one of two things: 2010 was a less than great year for movies, or he finally realized the mistake he made. Well, perhaps both?

A Brief History of Time (1991)

It is a fascinating time

Errol Morris's "A Brief History of Time" manages to be, in its succinct 80 minutes, a moving biopic and a thought-provoking documentary. Based on the best-selling book of the same name by British cosmologist Stephen Hawking (1942- ), it is accessible for those who are not science experts (without being condescending), yet still have an interest in questions about the origins of the universe and, therefore, ourselves (will time ever come to an end? which came first, the chicken or the egg?; and so on).

Featuring interviews with the Hawkings (Isobel and Mary Hawkings, Stephen's mom and sister, respectively), Janet Humphrey (Stephen's aunt), several people related to the world of science (astrophysicists, professors, researchers, etc.), plus interviews and clips from lectures with Mr. Hawkings himself, we reflect on some of the most fundamental questions about our creation. The beyond reasonable, sensible and bright conclusions presented by this man whose body might be paralyzed, but whose mind is one of the greatest of all time (few would argue against this statement) make this film both a fascinating lecture (or, even better, meditation) and an inspirational life story. And with his fantastic reasoning and suavity, Hawkings ends up proving (as far as reasoning can prove, or define, the power of faith), the very existence of God. A great achievement of filmmaking, perception, philosophy, science, and perseverance. Bravo, Mr. Hawkings. Bravo, Mr. Errol Morris.

Hoop Dreams (1994)

More than just a 'basketball documentary'

I'd heard a lot about this documentary, but had never seen it. I've even read comments by few people calling it their favourite film, "even though it's a documentary" (as if that was a bad thing!). It's understandable to see why this film speaks to the hearts of so many people.

"Hoop Dreams" follows two teenaged Chicago residents, Arthur Agee and William Gates, and their dreams of becoming professional basketball players - more than that, basketball superstars a la Michael Jordan. From their first year of high school until they start college, we observe all of the expectations, efforts, joy, disappointments, and numerous obstacles that make their journey.

Will Agee and Gates manage to overcome all the obstacles and become more than most of their peers even dream to achieve? The suspense is well-built through clever editing and a good sense of rhythm, pace and storytelling (documenting is also storytelling, after all), and the film doesn't feel 170 minutes long. By the end, you realize you've watched two real people growing up and doing what they can or cannot - failing and trying again - to achieve their goals and dreams, no matter what are the odds imposed by their economical and social backgrounds. Hoop Dreams come(s) true as both a slice of life and a fascinating socio-anthropological study. Not bad for a 'basketball documentary'.

Harvard Beats Yale 29-29 (2008)

For the love of the game.

Kevin Rafferty's ("The Atomic Cafe") new documentary shows us the historical match between Yale's and Harvard's undefeated football teams, in Cambridge, back in November 1968. The Vietnam War was roaring, birth control was a brand new wonder, and these 20 year-olds were meant to give their best in the greatest match of their lives. Through contemporary interviews with the players (including Harvard graduate and Oscar-winning actor Tommy Lee Jones), now forty years older and wiser, plus the actual game's footage with instant replay, we're transported to that exhilarating moment in time - the game and the era.

Rafferty's film's best qualities - nostalgia, portrayal of an era, love of the game - should be praised; yet, it didn't always work for me. Don't get me wrong, it's a fine documentary, and I'm personally fascinated by the 1960's (it's not because I wasn't even born then that I wouldn't be interested in it!), but the main issue, with me, is the football match itself. Brazilians, myself included, just can't understand American football and its rules (I'm an even worse case since I don't even enjoy soccer; I know, shame on me!). And even though I'm not a big basketball fan either, a movie like "Hoop Dreams" managed to engage me throughout because of the humanity of its characters and the visual and narrative vigor of that long film. Not to say the players in "Harvard Beats Yale 29-29" aren't charismatic or remotely interesting; they are. But I believe being a football fan helps a lot in order to fully enjoy this film. My verdict: a fine documentary, but the thematic sport just isn't for me.

Virginia (2010)

There's nothing wrong with Virginia, but there might be a mormon boy in her closet!

I was fortunate enough to attend the world premiere of Dustin Lance Black's highly personal, unique, and heartfelt new film, "What's Wrong With Virginia", in Toronto. The film owns a quirky charm that reminds me of Tony Richardson's "The Hotel New Hampshire" (1984, based on John Irving's novel), yet with its own very personal style. Jennifer Connelly, more beautiful than ever at 39, gives her best performance since 2003's "House of Sand and Fog". She plays Virginia Nicholaus, a mentally ill single mom who's had an affair with the local Mormon (and married) Sheriff Dick Tipton (Ed Harris, great as always) for 16 years. Her teenaged son, Emmett (newcomer Harrison Gilbertson, very convincing and simply adorable) is her only real love, and their relationship is the real core of the film (Black has stated the film is loosely based on his relationship with his mom). Things get complicated when Emmett - who may or may not be the Sheriff's son - starts dating Dick's daughter, Jessie Tipton (Emma Roberts), and how that and an unwelcome 'revelation' by Virginia can ruin Dick's political goals and marriage.

Black, who won a much deserved Best Original Screenplay Oscar for Gus Van Sant's "Milk" (and gave a groundbreaking, already classic acceptance speech), is not just a terrific writer, but also a natural actor's director. He extracts great performances from his ensemble, and although this is clearly Connelly's show, other cast members deserve to be mentioned: Amy Madigan, married to Ed Harris in real life and in the film, gives a moving, understated performance that could've easily been overplayed/clichéd; she's one of our most underrated character actresses. Carrie Preston, of "True Blood" fame and the best thing about "Duplicity", plays Virginia's friend Betty with gusto, and Toby Jones ("Infamous") is great in a character that starts out as creepy to later become human and even endearing. Yeardley Smith, mostly known as the voice of Lisa Simpson, also has a small part and is one of the executive producers of the film (Christine Vachon and Gus Van Sant himself, who don't get involved with just any kind of material, are some of the others who helped bring this project to life).

"What's Wrong With Virginia" provides lots of laughs and a considerable emotional punch that almost made me sob by the end. It's humorous and outrageous, tragic yet optimistic; it made me feel a range of emotions that most films out there fall short of. Well done, again, Mr. Black! It's comforting to know real auteurs are still blossoming in the world of cinema.

Harlan County U.S.A. (1976)

'There's blood upon your contract like vinegar in your wine...

...'cause there's one man dead on the Harlan County line'.

This is a powerful Oscar-winning documentary produced and directed by Barbara Kopple ('American Dream', 'Wild Man Blues'). It focuses on the men at the Brookside Mine in Harlan, Kentucky who, in the summer of 1973, voted to join the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA). Duke Power Company and its subsidiary, Eastover Mining Company, refused to sign the contract. The miners came out on a long strike, registered by Kopple with testimonies, backstories, archival footage, and music, particularly that of Hazel Dickens during the final credits.

The film's main strength resides in the sincerity of its emotional, political and sociological core without being overtly sentimental, and Kopple's way of testifying instead of exploiting the subjects. The miners and their wives are not depicted in old hillbilly stereotypes, but rather as hard-working human beings fighting for their basic rights ('together we stand, divided we fall').

Thirty years after the release of this documentary, five miners died in an explosion at Harlan County. When the film was shot, money was the bigger issue (industry profits rose 170% in 1975, but miner's wages rose only 4%); nowadays, however, safety is an even bigger issue. You'd think things would have been largely improved since then, but that's not really the case. 'Harlan County U.S.A.' is a remarkable documentary because it testifies and proposes solutions about a public struggle that shouldn't be overlooked, yet has been for such a long time, in the "land of the free and home of the brave".

Bandit Queen (1994)

Phoolan Devi, Bandit Queen

"Bandit Queen" is a controversial and groundbreaking Indian film (co-produced by Great Britain's "Channel Four") telling the real-life story of Phoolan Devi (Seema Biswas, excellent), a low-caste woman given to a husband at age 11 who runs away from him, is constantly violated by upper-caste males, until pairing with a handsome outlaw, Vikram Mallah (Nirmal Pandey), who shows her some respect and invites her to join his gang. Devi became a mythical national figure in her own lifetime (she had just been released from an 11-year prison term when the movie came out, and was murdered in 2001), hailed as "The Bandit Queen" or "Queen of the Ravines". Although at first Devi took legal action to ban the movie's exhibition in India (and it was actually banned for some time - after all, this is no Bollywood fantasy), she eventually changed her mind (plus, Channel Four paid her $60,000...).

A lot has been said about the accuracy of everything portrayed on screen ("My life was much harder", Devi would have said after the first time she saw the movie). Just like he would do in 1998's successful "Elizabeth", Shekhar Kapur knows how to turn a larger than life, actual trajectory in a huge spectacle - but still keeping the essence of its core. Truth be told, this is one of those extraordinary sagas that if even half of what's portrayed on screen is real, it's already quite a journey. Kapur might have been a high-caste, city-bred man trying to portray the life of a brave and rebellious low-caste woman fighting for her survival - in a way that no other woman in her time had done, but that doesn't mean he doesn't know or doesn't have the right to try to depict this reality he doesn't directly belong to. How honest Kapur's original intentions were we can't know for sure, but that doesn't undermine his accomplishment here; this is a story that had to be told to a larger international audience. If a movie manages to work both as an adventurous spectacle and a tale of resurgence after national injustice and misfortunes, then it deserves to be seen. 8.5/10.

Boyz n the Hood (1991)

"Rick, it's the Nineties. Can't afford to be afraid of our own people anymore, man"

John Singleton's first and most successful film to date (and, I'm positive, his best work too) is an honest account of three black friends (played, in their teens, by Cuba Gooding Jr., Ice Cube and Morris Chestnut) growing up in a South Central LA ghetto.

Ice Cube's song "AmeriKKKa's Most Wanted" partially inspired the story, which is also partially autobiographic. Like the protagonist Tre (Gooding Jr.), Singleton lived with his mother (played by Angela Bassett in the film) for his first years, and was sent to his father's (Laurence Fishburne) when she felt the place she was living in wasn't suitable for the 10 year-old, and it was about time his dad taught him "how to be a man". The other protagonists, Ricky (Chestnut) and Doughboy (Cube) are half brothers who couldn't be more different: Ricky is their mother's favorite, the athlete pursuing a football scholarship to USC and their mom's pride and joy, while Doughboy is the overweight, overlooked 17 year-old ex-con.

"Boyz N the Hood" starts with sad statistics: "One out of every 21 black males will die of murder, most of them at each other's hands". Singleton, who was only 23 when the film was made (he became not only the youngest ever Oscar nominee for Best Director, but also the first African American to be nominated in that category; only this year another African American would be nominated, Lee Daniels of "Precious", exactly 18 years later), told a story of how the reality of one's environment and upbringing are definitely huge factors in how one's personality and life choices are shaped and/or limited; yet, it still remains one's own struggle in the end. The rebellion here is the struggle to get out of a rotten environment you alone aren't strong enough to change, without being killed by it before then. It's a struggle only those who have been there know entirely, and for those of us who are fortunate enough to have been raised in better or at least not as violent environments, we can imagine and analyze through statistics, but not with an inner understanding of what living in such reality is like - lucky us. In that sense, Singleton's film reminds me of Fernando Meirelles's masterpiece "City of God" (2002), which presents an even tougher, scarier reality in Brazilian "favelas", which, as a Brazilian myself, I can tell you it's all true (sadly). The musical score is corny and easily the weakest link in the film, and some moments seem clichéd and contrived; but you can't deny the impact and overall honesty of this brutal effort from this young director. Not as multi-layered or even ambitious as Spike Lee's "Do the Right Thing", but still a film that remains relevant in 2010. 8.5/10.

Sans toit ni loi (1985)

"You chose total freedom and you got total loneliness"

Born in 1928, Agnes Varda ("Cleo from 5 to 7"), the only female director prominent during the Nouvelle Vague and arguably the most iconic woman behind the cameras alive, brought us in 1985 a remarkable character study/road movie, "Vagabond" (or, in the original French title, "Sans Toit Ni Loi", or "Without Roof or Laws"). 18 year-old Sandrine Bonnaire plays Mona Bergeron, who's found frozen to death in a ditch at the beginning of the movie. Through a series of flashbacks and interviews with people who met Mona, we're shown how just her sheer presence, words and actions, as nihilistic as they seemed, touched, one way or another, all of those who came into contact with her.

The sequence with the philosopher/farmer, his wife, their child and Mona could be my favourite. Their conversation define both the similarities and dissidence between their perceptions. They're very different people, but equally fascinating in their own ways/ideas of what's right and good. Mona is the title and theme of the film, "without roof or laws", when every other character falls under the restrictions of roof/laws (Lydie's greedy nephew and his wife), or about one roof and their philosophy (the farmer and his wife), while Mona is the only one without either - as the philosopher tells her, "You chose total freedom and you got total loneliness". That's Mona's cross and the theme of the film, in my opinion - while her response "Champagne on the road's better!" to the question "Why did you drop out?" represents her attitude towards her own life. Whether champagne's better on the road or not is for you to decide, but one thing is for sure: this film makes you think, about others' and your own attitude towards social issues and the meaning of living in the society you're a part of. And, above all, about the free will to change your reality or conform to it. 10/10.