Bayes factor

Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'strict' not found.

In statistics, the use of Bayes factors is a Bayesian alternative to classical hypothesis testing.[1][2] Bayesian model comparison is a method of model selection based on Bayes factors.

Definition

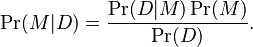

The posterior probability Pr(M|D) of a model M given data D is given by Bayes' theorem:

The key data-dependent term Pr(D|M) is a likelihood, and represents the probability that some data are produced under the assumption of this model, M; evaluating it correctly is the key to Bayesian model comparison.

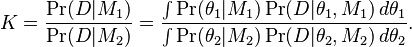

Given a model selection problem in which we have to choose between two models, on the basis of observed data D, the plausibility of the two different models M1 and M2, parametrised by model parameter vectors  and

and  is assessed by the Bayes factor K given by

is assessed by the Bayes factor K given by

If instead of the Bayes factor integral, the likelihood corresponding to the maximum likelihood estimate of the parameter for each model is used, then the test becomes a classical likelihood-ratio test.[citation needed] Unlike a likelihood-ratio test, this Bayesian model comparison does not depend on any single set of parameters, as it integrates over all parameters in each model (with respect to the respective priors). However, an advantage of the use of Bayes factors is that it automatically, and quite naturally, includes a penalty for including too much model structure.[3] It thus guards against overfitting. For models where an explicit version of the likelihood is not available or too costly to evaluate numerically, approximate Bayesian computation can be used for model selection in a Bayesian framework,[4] with the caveat that approximate-Bayesian estimates of Bayes factors are often biased.[5]

Other approaches are:

- to treat model comparison as a decision problem, computing the expected value or cost of each model choice;

- to use minimum message length (MML).

Interpretation

A value of K > 1 means that M1 is more strongly supported by the data under consideration than M2. Note that classical hypothesis testing gives one hypothesis (or model) preferred status (the 'null hypothesis'), and only considers evidence against it. Harold Jeffreys gave a scale for interpretation of K:[6]

-

K dHart bits Strength of evidence < 100 < 0 negative (supports M2) 100 to 101/2 0 to 5 0 to 1.6 barely worth mentioning 101/2 to 101 5 to 10 1.6 to 3.3 substantial 101 to 103/2 10 to 15 3.3 to 5.0 strong 103/2 to 102 15 to 20 5.0 to 6.6 very strong > 102 > 20 > 6.6 decisive

The second column gives the corresponding weights of evidence in decihartleys (also known as decibans); bits are added in the third column for clarity. According to I. J. Good a change in a weight of evidence of 1 deciban or 1/3 of a bit (i.e. a change in an odds ratio from evens to about 5:4) is about as finely as humans can reasonably perceive their degree of belief in a hypothesis in everyday use.[7]

An alternative table, widely cited, is provided by Kass and Raftery (1995):[3]

-

2 ln K K Strength of evidence 0 to 2 1 to 3 not worth more than a bare mention 2 to 6 3 to 20 positive 6 to 10 20 to 150 strong >10 >150 very strong

The use of Bayes factors or classical hypothesis testing takes place in the context of inference rather than decision-making under uncertainty. That is, we merely wish to find out which hypothesis is true, rather than actually making a decision on the basis of this information. Frequentist statistics draws a strong distinction between these two because classical hypothesis tests are not coherent in the Bayesian sense. Bayesian procedures, including Bayes factors, are coherent, so there is no need to draw such a distinction. Inference is then simply regarded as a special case of decision-making under uncertainty in which the resulting action is to report a value. For decision-making, Bayesian statisticians might use a Bayes factor combined with a prior distribution and a loss function associated with making the wrong choice. In an inference context the loss function would take the form of a scoring rule. Use of a logarithmic score function for example, leads to the expected utility taking the form of the Kullback–Leibler divergence.

Example

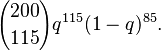

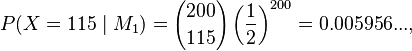

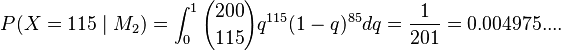

Suppose we have a random variable that produces either a success or a failure. We want to compare a model M1 where the probability of success is q = ½, and another model M2 where q is unknown and we take a prior distribution for q that is uniform on [0,1]. We take a sample of 200, and find 115 successes and 85 failures. The likelihood can be calculated according to the binomial distribution:

Thus we have

but

The ratio is then 1.197..., which is "barely worth mentioning" even if it points very slightly towards M1.

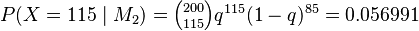

This is not the same as a classical likelihood-ratio test, which would have found the maximum likelihood estimate for q, namely 115⁄200 = 0.575, whence  (rather than averaging over all possible q). That gives a likelihood ratio of 0.1045, and so pointing towards M2.

(rather than averaging over all possible q). That gives a likelihood ratio of 0.1045, and so pointing towards M2.

The modern method of relative likelihood takes into account the number of free parameters in the models, unlike the classical likelihood ratio. The relative likelihood method could be applied as follows. Model M1 has 0 parameters, and so its AIC value is 2·0 − 2·ln(0.005956) = 10.2467. Model M2 has 1 parameter, and so its AIC value is 2·1 − 2·ln(0.056991) = 7.7297. Hence M1 is about exp((7.7297 − 10.2467)/2) = 0.284 times as probable as M2 to minimize the information loss. Thus M2 is slightly preferred, but M1 cannot be excluded.

A frequentist hypothesis test of M1 (here considered as a null hypothesis) would have produced a very different result. Such a test says that M1 should be rejected at the 5% significance level, since the probability of getting 115 or more successes from a sample of 200 if q = ½ is 0.0200, and as a two-tailed test of getting a figure as extreme as or more extreme than 115 is 0.0400. Note that 115 is more than two standard deviations away from 100.

M2 is a more complex model than M1 because it has a free parameter which allows it to model the data more closely. The ability of Bayes factors to take this into account is a reason why Bayesian inference has been put forward as a theoretical justification for and generalisation of Occam's razor, reducing Type I errors.[8]

See also

- Akaike information criterion

- Approximate Bayesian Computation

- Bayesian information criterion

- Deviance information criterion

- Lindley's paradox

- Minimum message length

- Model selection

- Statistical ratios

Notes

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'strict' not found.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'strict' not found.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'strict' not found.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'strict' not found.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'strict' not found.

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'strict' not found. p. 432

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'strict' not found.

- ↑ Sharpening Ockham's Razor On a Bayesian Strop

References

- Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'strict' not found.

- Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'strict' not found.

- Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'strict' not found.

- Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'strict' not found.

- Jaynes, E. T. (1994), Probability Theory: the logic of science, chapter 24.

- Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'strict' not found.

- Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'strict' not found.

External links

- BayesFactor —an R package for computing Bayes factors in common research designs

- Bayes Factor Calculators —web-based version of much of the BayesFactor package