Oceanic basin

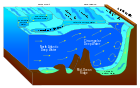

In hydrology, an oceanic basin may be anywhere on Earth that is covered by seawater, but geologically ocean basins are large geologic basins that are below sea level. Geologically, there are other undersea geomorphological features such as the continental shelves, the deep ocean trenches, and the undersea mountain ranges (for example, the mid-Atlantic ridge and the Emperor Seamounts) which are not considered to be part of the ocean basins; while hydrologically, oceanic basins include the flanking continental shelves and shallow, epeiric seas.

History

Older references (e.g., Littlehales 1930)[1] consider the oceanic basins to be the complement to the continents, with erosion dominating the latter, and the sediments so derived ending up in the ocean basins. More modern sources (e.g., Floyd 1991)[2] regard the ocean basins more as basaltic plains, than as sedimentary depositories, since most sedimentation occurs on the continental shelves and not in the geologically-defined ocean basins.[3]

Hydrologically some geologic basins are both above and below sea level, such as the Maracaibo Basin in Venezuela, although geologically it is not considered an oceanic basin because it is on the continental shelf and underlain by continental crust.

Earth is the only known planet in the solar system where hypsography is characterized by different kinds of crust, oceanic crust and continental crust.[4] Oceans cover 70% of the Earth's surface. Because oceans lie lower than continents, the former serve as sedimentary basins that collect sediment eroded from the continents, known as clastic sediments, as well as precipitation sediments. Ocean basins also serve as repositories for the skeletons of carbonate- and silica-secreting organisms such as coral reefs, diatoms, radiolarians, and foraminifera.

Geologically, an oceanic basin may be actively changing size or may be relatively, tectonically inactive, depending on whether there is a moving plate tectonic boundary associated with it. The elements of an active - and growing - oceanic basin include an elevated mid-ocean ridge, flanking abyssal hills leading down to abyssal plains. The elements of an active oceanic basin often include the oceanic trench associated with a subduction zone.

The Atlantic ocean and the Arctic ocean are good examples of active, growing oceanic basins, whereas the Mediterranean Sea is shrinking. The Pacific Ocean is also an active, shrinking oceanic basin, even though it has both spreading ridge and oceanic trenches. Perhaps the best example of an inactive oceanic basin is the Gulf of Mexico, which formed in Jurassic times and has been doing nothing but collecting sediments since then.[5] The Aleutian Basin[6] is another example of a relatively inactive oceanic basin. The Japan Basin in the Sea of Japan which formed in the Miocene, is still tectonically active although recent changes have been relatively mild.[7]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Littlehales, G. W. (1930) The configuration of the oceanic basins Graficas Reunidas, Madrid, Spain, OCLC 8506548

- ↑ Floyd, P. A. (1991) Oceanic basalts Blackie, Glasgow, Scotland, ISBN 978-0-216-92697-4

- ↑ Biju-Duval, Bernard (2002) Sedimentary geology: sedimentary basins, depositional environments, petroleum formation Editions Technip, Paris, ISBN 978-2-7108-0802-2

- ↑ Ebeling, Werner and Feistel, Rainer (2002) Physics of Self-Organization and Evolution Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, Germany, page 141, ISBN 978-3-527-40963-1

- ↑ Huerta, Audrey D. and Harry, Dennis L. (2012) "Wilson cycles, tectonic inheritance, and rifting of the North American Gulf of Mexico continental margin" Geosphere 8(2): pp. 374–385, first published on March 6, 2012, doi:10.1130/GES00725.1

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'strict' not found.

- ↑ Clift, Peter D. (2004) Continent-Ocean Interactions Within East Asian Marginal Seas American Geophysical Union, Washington, D.C., pages 102–103, ISBN 978-0-87590-414-6

Further reading

- Wright, John et al. (1998) The Ocean Basins: Their Structure and Evolution (Second edition) Open University, Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford, England, ISBN 978-0-7506-3983-5; for pay electronic version available from ScienceDirect here