Z-buffering

In computer graphics, z-buffering, also known as depth buffering, is the management of image depth coordinates in 3D graphics, usually done in hardware, sometimes in software. It is one solution to the visibility problem, which is the problem of deciding which elements of a rendered scene are visible, and which are hidden. The painter's algorithm is another common solution which, though less efficient, can also handle non-opaque scene elements.

When an object is rendered, the depth of a generated pixel (z coordinate) is stored in a buffer (the z-buffer or depth buffer). This buffer is usually arranged as a two-dimensional array (x-y) with one element for each screen pixel. If another object of the scene must be rendered in the same pixel, the method compares the two depths and overrides the current pixel if the object is closer to the observer. The chosen depth is then saved to the z-buffer, replacing the old one. In the end, the z-buffer will allow the method to correctly reproduce the usual depth perception: a close object hides a farther one. This is called z-culling.

The granularity of a z-buffer has a great influence on the scene quality: a 16-bit z-buffer can result in artifacts (called "z-fighting" or stitching) when two objects are very close to each other. A 24-bit or 32-bit z-buffer behaves much better, although the problem cannot be entirely eliminated without additional algorithms. An 8-bit z-buffer is almost never used since it has too little precision.

Contents

Uses

The Z-buffer is a technology used in almost all contemporary computers, laptops and mobile phones for performing 3D graphics, for example for computer games. The Z-buffer is implemented as hardware in the silicon ICs (integrated circuits) within these computers. The Z-buffer is also used (implemented as software as opposed to hardware) for producing computer-generated special effects for films.

Furthermore, Z-buffer data obtained from rendering a surface from a light's point-of-view permits the creation of shadows by the shadow mapping technique.

Developments

Even with small enough granularity, quality problems may arise when precision in the z-buffer's distance values is not spread evenly over distance. Nearer values are much more precise (and hence can display closer objects better) than values which are farther away. Generally, this is desirable, but sometimes it will cause artifacts to appear as objects become more distant. A variation on z-buffering which results in more evenly distributed precision is called w-buffering (see below).

At the start of a new scene, the z-buffer must be cleared to a defined value, usually 1.0, because this value is the upper limit (on a scale of 0 to 1) of depth, meaning that no object is present at this point through the viewing frustum.

The invention of the z-buffer concept is most often attributed to Edwin Catmull, although Wolfgang Straßer also described this idea in his 1974 Ph.D. thesis1.

On recent PC graphics cards (1999–2005), z-buffer management uses a significant chunk of the available memory bandwidth. Various methods have been employed to reduce the performance cost of z-buffering, such as lossless compression (computer resources to compress/decompress are cheaper than bandwidth) and ultra fast hardware z-clear that makes obsolete the "one frame positive, one frame negative" trick (skipping inter-frame clear altogether using signed numbers to cleverly check depths).

Z-culling

In rendering, z-culling is early pixel elimination based on depth, a method that provides an increase in performance when rendering of hidden surfaces is costly. It is a direct consequence of z-buffering, where the depth of each pixel candidate is compared to the depth of existing geometry behind which it might be hidden.

When using a z-buffer, a pixel can be culled (discarded) as soon as its depth is known, which makes it possible to skip the entire process of lighting and texturing a pixel that would not be visible anyway. Also, time-consuming pixel shaders will generally not be executed for the culled pixels. This makes z-culling a good optimization candidate in situations where fillrate, lighting, texturing or pixel shaders are the main bottlenecks.

While z-buffering allows the geometry to be unsorted, sorting polygons by increasing depth (thus using a reverse painter's algorithm) allows each screen pixel to be rendered fewer times. This can increase performance in fillrate-limited scenes with large amounts of overdraw, but if not combined with z-buffering it suffers from severe problems such as:

- polygons might occlude one another in a cycle (e.g. : triangle A occludes B, B occludes C, C occludes A), and

- there is no canonical "closest" point on a triangle (e.g.: no matter whether one sorts triangles by their centroid or closest point or furthest point, one can always find two triangles A and B such that A is "closer" but in reality B should be drawn first).

As such, a reverse painter's algorithm cannot be used as an alternative to Z-culling (without strenuous re-engineering), except as an optimization to Z-culling. For example, an optimization might be to keep polygons sorted according to x/y-location and z-depth to provide bounds, in an effort to quickly determine if two polygons might possibly have an occlusion interaction.

Mathematics

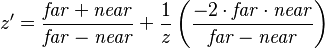

The range of depth values in camera space (see 3D projection) to be rendered is often defined between a  and

and  value of

value of  . After a perspective transformation, the new value of

. After a perspective transformation, the new value of  , or

, or  , is defined by:

, is defined by:

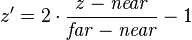

After an orthographic projection, the new value of  , or

, or  , is defined by:

, is defined by:

where  is the old value of

is the old value of  in camera space, and is sometimes called

in camera space, and is sometimes called  or

or  .

.

The resulting values of  are normalized between the values of -1 and 1, where the

are normalized between the values of -1 and 1, where the  plane is at -1 and the

plane is at -1 and the  plane is at 1. Values outside of this range correspond to points which are not in the viewing frustum, and shouldn't be rendered.

plane is at 1. Values outside of this range correspond to points which are not in the viewing frustum, and shouldn't be rendered.

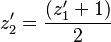

Fixed-point representation

Typically, these values are stored in the z-buffer of the hardware graphics accelerator in fixed point format. First they are normalized to a more common range which is [0,1] by substituting the appropriate conversion  into the previous formula:

into the previous formula:

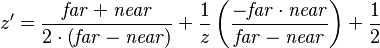

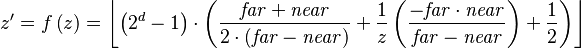

Second, the above formula is multiplied by  where d is the depth of the z-buffer (usually 16, 24 or 32 bits) and rounding the result to an integer:[1]

where d is the depth of the z-buffer (usually 16, 24 or 32 bits) and rounding the result to an integer:[1]

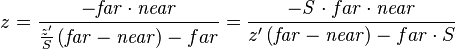

This formula can be inverted and derived in order to calculate the z-buffer resolution (the 'granularity' mentioned earlier). The inverse of the above  :

:

where

The z-buffer resolution in terms of camera space would be the incremental value resulted from the smallest change in the integer stored in the z-buffer, which is +1 or -1. Therefore this resolution can be calculated from the derivative of  as a function of

as a function of  :

:

Expressing it back in camera space terms, by substituting  by the above

by the above  :

:

~

This shows that the values of  are grouped much more densely near the

are grouped much more densely near the  plane, and much more sparsely farther away, resulting in better precision closer to the camera. The smaller the

plane, and much more sparsely farther away, resulting in better precision closer to the camera. The smaller the  ratio is, the less precision there is far away—having the

ratio is, the less precision there is far away—having the  plane set too closely is a common cause of undesirable rendering artifacts in more distant objects.[2]

plane set too closely is a common cause of undesirable rendering artifacts in more distant objects.[2]

To implement a z-buffer, the values of  are linearly interpolated across screen space between the vertices of the current polygon, and these intermediate values are generally stored in the z-buffer in fixed point format.

are linearly interpolated across screen space between the vertices of the current polygon, and these intermediate values are generally stored in the z-buffer in fixed point format.

W-buffer

To implement a w-buffer,[clarification needed] the old values of  in camera space, or

in camera space, or  , are stored in the buffer, generally in floating point format. However, these values cannot be linearly interpolated across screen space from the vertices—they usually have to be inverted[disambiguation needed], interpolated, and then inverted again. The resulting values of

, are stored in the buffer, generally in floating point format. However, these values cannot be linearly interpolated across screen space from the vertices—they usually have to be inverted[disambiguation needed], interpolated, and then inverted again. The resulting values of  , as opposed to

, as opposed to  , are spaced evenly between

, are spaced evenly between  and

and  . There are implementations of the w-buffer that avoid the inversions altogether.

. There are implementations of the w-buffer that avoid the inversions altogether.

Whether a z-buffer or w-buffer results in a better image depends on the application.

See also

- Edwin Catmull

- 3D computer graphics

- 3D scanner

- Z-fighting

- Irregular Z-buffer

- Z-order

- z-index

- Hierarchical Z-buffer

- A-buffer

- Depth map

- Atmospheric perspective

- HyperZ

References

External links

Notes

Note 1: see W.K. Giloi, J.L. Encarnação, W. Straßer. "The Giloi’s School of Computer Graphics". Computer Graphics 35 4:12–16.