by James Harvey McClintock

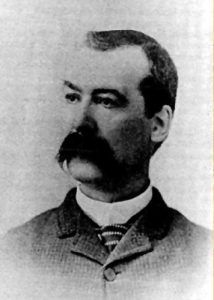

Captain Burton Mossman of the Arizona Rangers

The organization of the Arizona Rangers was on the recommendation of Governor Murphy to the Legislature in 1901. The first Captain appointed was Burton C. Mossman, a Northern Arizona cattleman, who proceeded with an organization of a company that, at first, consisted of only 12 men, with Dayton Graham of Cochise County as the first lieutenant.

Mossman made his organization wholly non-political, and men were sought for enlistment on account of their records as efficient officers, good shots and good frontiersmen, well acquainted with the country. In some cases, men were enlisted whose previous records would not have entitled them to distinguished consideration in a Sunday school but who had a reputation for courage and endurance. Such men usually gave a very good account of themselves.

According to Mossman: “I have never known a body of men to take a more intense interest in their work. They were very proud of the organization, proud of the record that they were making, and there was great emulation among the men to make good.”

Every section of the territory had its representatives so that wherever the command might be called, there would be some ranger familiar with the country, water holes, trails, etc. During the first twelve months after organization, 125 arrests were made of actual criminals, who were sent to the penitentiary or back to other states to answer for the crime. The deterrent effect of these many captures was great, serving to drive from the territory a large percentage of its criminal population.

Organized in August, the rangers proved effective from the first. In November, two of its members, Carlos Tafolla and Dean Hamblin, reinforced by four Saint Johns cattlemen, chased the Jack Smith band of outlaws into the Black River country south of Springerville. The outlaws were headed for Mexico with a band of stolen horses and were surprised while in camp.

Horse Thieves

After the apparent surrender, they dodged behind trees and opened fire. Tafolla and a cattleman named Maxwell were killed, and two outlaws were wounded. The latter escaped in the darkness on foot, leaving their camp outfit and horses behind. Captain Mossman, with three more rangers, were soon on the trail but the gang stealing fresh horses managed to escape in the snows of the New Mexican mountains. Tafolla’s widow was pensioned by the Legislature.

Captain Mossman early established amicable relations with the Mexican authorities, and an agreement was entered into with Lt. Col. Kosterlitsky of the Mexican Rurales that either should have the privilege of chasing outlaws across the border and they should work in unison with the definite objective of ridding the Southwest of the “rustler” element.

In 1903 the force embraced 26 officers. Six years after the organization, a report was made that the rangers had made 4,000 arrests, of which 25% had been for serious felonies. The best work was against horse and cattle thieves.

Special value was found in the fact that the Rangers were independent of politics and were not controlled by considerations that often tied the hands of local peace officers. This very feature, however, led to occasional trouble with disagreeing sheriffs.

After Governor Brodie assumed office, a change was made in the leadership of the Arizona Rangers to the position appointed T.H. Rynning, who had been a lieutenant of Rough Riders. Under him, the organization did splendid work, especially in the labor troubles in Bisbee and Morenci. At the latter point, one episode most worthy of mention was when a band of several hundred rioters, coming over the divide from Chase Creek, encountered a few rangers commanded by Sergeant Jack Foster. Foster was hailed, and a demand was made upon him for his guns. The sergeant, remembering his experience in the Rough Riders, deployed his men along the crest of a ridge and laconically answered:” If you want the guns, come and get them.” The rioters decided to move on, and Foster saved his rifle and self-respect.

The history of the rangers, under whatever leadership, was one of devotion and rare courage, well worthy of a separate volume. Some of it is told in this work, but much is left unchronicled. There is the story of how Ranger Frank Wheeler, with Deputy Sheriff John Cameron, killed Herrick and Bentley, former convicts wanted for horse stealing, in the course of a battle in the rocks after the fugitives had been tracked for five days. There might be mentioned, as typical, the encounter in Benson of Captain Harry Wheeler with a desperado named Tracy, wherein the latter died with four bullet holes in his body, and Wheeler received wounds that disabled him for months. There was the case of Willis Wood, an outlaw of the worst type, who was taken by [Thomas] Rynning from a roomful of the prisoner’s friends.

Rynning resigned to become superintendent of the territorial prison during its reconstruction at Florence, and on March 21, 1907, was succeeded by his lieutenant, Harry Wheeler, later sheriff of Cochise County. Wheeler was notably successful in handling difficult border conditions. But politics finally caused the disbandment of the rangers*.

Written by James Harvey McClintock in 1913, compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated November 2022.

*Note: As McClintock’s writing of the Arizona Rangers occurred in 1913, he couldn’t have known that the Rangers would be revived in 1957 by a group of several original Arizona Rangers.

The present-day Arizona Rangers are an unpaid, all-volunteer, law enforcement support and assistance civilian auxiliary. They work co-operatively at the request of and under established law enforcement officials and officers’ direction, control, and supervision. They also provide youth support and community service and work to preserve the tradition, honor, and history of the original Arizona Rangers.

Notes and Author: James Harvey McClintock was born in Sacramento in 1864 and moved to Arizona at the age of 15, working for his brother at the Salt River Herald (later known as the Arizona Republic). When McClintock was 22, he began to attend the Territorial Normal School in Tempe, where he earned a teaching certificate. Later, he would serve as Theodore Roosevelt’s right-hand man in the Rough Riders during the Spanish-American War and become an Arizona State Representative. Between 1913 and 1916, McClintock published a three-volume history of Arizona called Arizona: The Youngest State (now in the public domain,) in which this article appeared. McClintock continued living in Arizona until his poor health forced him to return to California, where he died on May 10, 1934, at 70.

The article is not verbatim, as spelling errors and minor grammatical changes have been made.

Also See: