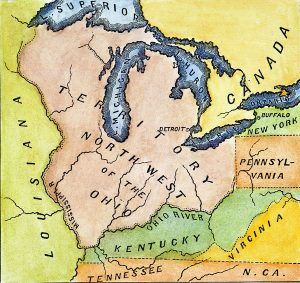

The Battle of Fallen Timbers, Ohio, on August 20, 1794, was the final battle of the Old Northwest Indian War. It was a struggle between Native American tribes affiliated with the Northwestern Confederacy and their British allies against the fledgling United States for control of the Northwest Territory.

The 1783 Treaty of Paris ended the Revolutionary War. However, it contained a provision that allowed the British to remain in the Northwest Territory until the United States resolved a land issue with Native Americans, who had been British allies. The Chippewa, Ottawa, Potawatomi, Shawnee, Delaware, Miami, and Wyandot tribes formed a federation to halt further U.S. incursions into their territory. After a stunning defeat of St. Clair’s American troops in 1791 by the Native American Federation under Chief Little Turtle, President George Washington put General Anthony Wayne, who had already established himself as one of the premier American officers in the Continental Army during the American Revolution, in charge of the Legion of the United States. The subsequent Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794 became the decisive point for resolving the U.S. jurisdiction of the Old Northwest Territory.

During the 1780s, apart from a few domestic disturbances, such as Shay’s rebellion in 1786, the primary threat to American security and to settlers attempting to establish new homesteads west of the Allegheny Mountains were Indians. With the assistance of British agents from Canada, who encouraged them to attack American settlers, some British officials hoped to establish an “independent” Indian state between the Ohio River and the Great Lakes, which would be a British puppet state. Furthermore, British troops still occupied several forts in the Northwest Territory they deemed essential to the fur trade, violating the treaty that officially ended the war with Britain.

In an attempt to crush the Indians attacking American settlers, the federal government ordered military expeditions into what is now Ohio. The first of these expeditions, led by Brigadier General Josiah Harmer, consisted of an expanded First American Regiment and 1,500 militiamen from Kentucky and Pennsylvania. Setting off from Fort Washington, near present-day Cincinnati, Ohio, Harmar’s force headed north towards the Miami Villages. Almost immediately, Harmar ran into problems, especially with supplies and integrating the militia into his force. Furthermore, while deep in Indian territory, Harmar divided his column, significantly weakening his Army. The Indians, led by Miami Chief Little Turtle, attacked Harmar’s troops on October 19 and 22, 1790, at the confluence of the St. Mary and St. Joseph Rivers and inflicted heavy casualties on Harmar’s militia and regulars. Harmar was forced to retreat to Fort Washington, and the disorderly retreat of Harmar’s expedition only served to embolden the Indian warriors.

Another expedition was organized to march into the Northwest Territory once again to deal with the threat posed to Major General Arthur St. Clair, the governor of the Northwest Territory and veteran of the Continental Army. In addition to the First American Regiment, a second infantry regiment had been raised to accompany the expedition. Kentucky militiamen and a few cavalrymen brought St. Clair’s Army up to approximately 1,400 men. St. Clair, ill and unfit to command the force, began marching his Army north from Fort Washington on September 17, 1791.

The march progressed slowly — by November, the expedition was only 90 miles from where it started. St. Clair weakened his force by detaching the First Regiment to find his overdue supply train. On November 4, Indians led by Little Turtle surprised and attacked the expedition along the upper Wabash River. In the ensuing battle, St. Clair’s force was utterly routed. The Indians slaughtered over 600 men, along with a large number of civilians accompanying the expedition. The wounded left on the battlefield were mercilessly scalped by the Indians. St. Clair ordered a full retreat, and the remaining troops limped back to Fort Washington. The defeat demonstrated that significant reforms were required if the Army was to become an effective fighting force against the Indians or any other potential enemy of the young republic.

Congress agreed to a reorganization of the Army. On March 5, 1792, Congress approved the reorganization of the Army as the Legion of the United States. The Army would be divided into four sub-legions of 1,280 men, each commanded by a brigadier general and comprised of two infantry battalions, one battalion of riflemen, one company of artillery, and one of the dragoons. This reorganization was believed to provide better tactical flexibility on the battlefield. Referring to the Army as the “Legion” also had a sentimental purpose, as the leaders of the young American republic often drew parallels to the Roman Republic.

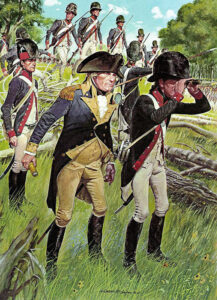

President George Washington and Secretary of War Henry Knox examined several candidates to lead the reorganized Army, including Henry “Light Horse Harry” Lee and Daniel Morgan. Still, it soon became clear there was only one obvious choice: Anthony Wayne. On the same day the Army reorganization was approved, Wayne was promoted to major general and named commanding general of the Legion of the United States.

Wayne was given significant time to train the soldiers under his command and put his stamp on the Army. For nearly two years, American delegates attempted to negotiate with the Indians, all to no avail. Once again, American troops would have to face hostile Indians. However, this time, they will be ready for the task.

Initially, Wayne began training the Legion at Fort Fayette, near the frontier town of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Like many frontier towns of the period, Pittsburgh thrived with vice, with General Wayne calling it “a frontier Gomorrah.” He, therefore, moved his troops 22 miles down the Ohio River to a place he named Legionville. At this site, Wayne implemented a rigorous training program for the Legion.

At Legionville, Wayne instilled discipline in his inexperienced troops. Secretary Knox had stated that “another conflict with raw recruits is to be avoided at all means.” He immediately provided all his officers down to the company level with copies of von Steuben’s Blue Book drill manual. He instructed them to use it until the Legion was familiar with close-order drills, hopefully preventing the troops from breaking and running on the battlefield. He instructed the men on the art of field fortifications; the troops learned to build redoubts and abatis to protect their encampments. The troops of the Legion learned to handle their muskets and use bayonets. Even more critical, Wayne stressed the importance of individual marksmanship, which the Army had neglected because of the high powder cost. To increase esprit de corps, Wayne gave each sub-legion distinctive colors for cap ornaments and uniform facings: white for the First sub-legion, red for the Second, yellow for the Third, and green for the Fourth. With the Legion trained, Wayne loaded his forces and floated them down the Ohio to Cincinnati and Fort Washington.

With his force near full strength, he marched north and established a new encampment, Fort Greene, named for Nathanael Greene. On December 25, 1793, an advance party arrived at the scene where St. Clair’s force had been massacred. They found a horrifying scene as hundreds of skeletons lay scattered about. On the site, Wayne’s forces established a new post, Fort Recovery, where some troops stayed for the winter while the rest remained encamped at Fort Greene.

On August 20, 1794, Major General Anthony Wayne led the Legion of the United States troops from their fort at Roche de Bout in the Maumee Valley of Ohio. Kentucky’s left-wing and flanking militia crossed level but poorly drained land containing dense forest and underbrush. After a five-mile march, the mounted volunteers came upon a line of 1,100 Indian warriors from a confederation of Ohio and Great Lakes Indian tribes. The militia volunteers retreated around the Legion’s front guard. The front guard returned fire while retreating but eventually fled. The warriors closely pursued the soldiers of the front guard until a light infantry skirmish line forced the Indians to seek shelter amid timbers that had been felled a few years before by a tornado. The Legion’s right wing was under heavy fire from the concealed warriors, who broke down an effort to flank them from the river. The left flank of soldiers charged, inflicting heavy casualties on the Indians and driving them from the field. Wayne’s scouts tracked them to the mouth of Swan Creek, but they were not engaged. After regrouping his troops, Wayne held his position into the afternoon. With no Indian counter-attack, Wayne set up camp on high ground overlooking the foot of the rapids, within sight of Fort Miami. In the following days, Wayne’s men returned to the battlefield to collect the wounded and gather equipment. Two officers and 15 to 17 soldiers were buried, but hard soil conditions deterred soldiers from burying more men. The entire Legion marched back through the battlefield on August 23 as they returned to Roche de Bout.

As a result of the Battle of Fallen Timbers, the Indians signed the Treaty of Greenville in 1795, which ceded strategic areas, including Detroit, Michigan, and control of most of the river crossings in the Old Northwest Territory to the United States. This essentially guaranteed U.S. domination over the Indian tribes. The 1796 Jay Treaty formally ended the British presence in the Old Northwest Territory, and troops withdrew from Fort Miami and the other forts. However, these treaties did not resolve the underlying issue. British naval power continued to dominate Lake Erie and the lower Maumee River while the Americans controlled the interior.

The War of 1812 finally settled the boundary and jurisdictional disputes. In 1813, General William Henry Harrison had Fort Meigs constructed as a winter encampment and supply base for the U.S. Army on the south bank of the Maumee River at present-day Perrysburg, Ohio. In the spring of 1813, the British landed troops and artillery at Fort Miami; while the fort was too deteriorated to be reoccupied, the British camped at the site and used it as a base of operations. The Shawnee Chief Tecumseh led the Indians who gathered to support the British. An army of British soldiers and Indians attacked Fort Meigs in April 1813, but the Americans held firm and the attackers withdrew in early May.

In July, the Indians persuaded the British to attack again, but this attack also failed. Britain’s failure to drive the Americans from the region convinced Harrison to go on the offensive. In October 1813, Harrison defeated a joint English and Indian Army at the Battle of the Thames. British occupation of the American Northwest ended as a result, and with the death of Tecumseh in the battle, hopes of building an Indian confederation ended. The Treaty of Ghent in 1815 ended the war, the British withdrew from American Territory, and Fort Meigs was abandoned.

Fort Miami

The British, with the support of the Indian Confederation, had constructed Fort Miami in the spring of 1794 to hold the Maumee Valley and stop Wayne’s advances toward Detroit. It also allowed the British to solidify Indian support against the U.S. settlers moving into the Ohio Territory. The fort consisted of four bastions surrounded by a 25-foot-deep trench lined with rows of stakes. The British also placed 14 cannons in the fort to thwart any attackers. Despite the promise from the British that the fort would offer protection to the Indians, warriors retreating to the fort were not allowed to enter and instead had to proceed to the mouth of Swan Creek. After the battle, General Wayne felt that Fort Miami was too strong to be forced, and he returned to Roche de Bout.

General ‘Mad’ Anthony Wayne was the commander of the Legion of the United States, supported by General Charles Scott’s Kentucky Militia, at the Battle of Fallen Timbers near present-day Toledo, Ohio. Wayne’s troops were victorious against a combined Native American force of Shawnee under Chief Blue Jacket, Ottawa under Egushawa, and many others. The battle was brief, lasting little more than an hour, but it scattered the confederated Native American forces. The U.S. victory ended significant hostilities in the region. The following Jay Treaty, on November 19, 1794, and the Treaty of Greenville, on August 3, 1795, forced Native Americans to leave most of modern-day Ohio, opening it to the American people in their quest for western expansion and the struggle for dominance in the Old Northwest Territory. The British presence withdrew from the southern Great Lakes region of the United States. During the Battle of Fallen Timbers, other chiefs were Tecumseh, Chief Blue Jacket, and Chief Bukongahelas. Tecumseh was one of the most famous leaders during the resistance but refused to sign the Treaty of Greenville in 1795.

A year later, ‘Mad’ Anthony Wayne died on December 15, 1796.

Today, Metroparks of the Toledo Area manage the Fallen Timbers Battlefield and Fort Miami National Historic Site. It is also an affiliated unit of the National Park Service. The national historic site consists of three separate areas:

– The Fallen Timbers Battlefield was the site of the 1794 battle between the United States military and a confederacy of American Indians backed by the British.

– The Fallen Timbers Monument was erected in 1929 to commemorate the battle.

– The site of Fort Miami, a British fort used during the 1794 campaign and again in the War of 1812.

Fallen Timbers Battlefield and Fort Miami National Historic Site in Ohio by the National Park Service.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, August 2024.

Also See:

Frontier Skirmishes between the Pioneers & the Indians

Military Campaigns of the Indian Wars

Sources: