By Hugh F. Rankin in 1960

More than any other, Blackbeard can be called North Carolina’s own pirate, although he was not a native of the colony and cannot be considered a credit to the Tar Heel State.

As with most pirates, his origin is obscure, though his name was said to have been Edward Drummond. He began his career as an honest seaman, sailing out of his home port of Bristol, England. But, after he became a pirate, he began calling himself Edward Teach. Yet it was as Blackbeard that he was, and still is, known, and under this name, the people of his generation knew him.

Perhaps Edward’s piratical tendencies were the result of his early environment. His hometown, Bristol, turned out more pirates in the 17th and 18th centuries than any other English port. As a young lad, he went to sea as a merchant seaman, and his first taste of adventure came in Queen Anne’s War, which lasted from 1701 to 1713. Towards the war’s latter stages, he served on a privateer, sailing out of Kingston in Jamaica to prey on French shipments.

The routine of peace following the excitement of warfare created a restlessness in the young man who was beginning to call himself Edward Teach. He signed on as a member of the pirate crew of Captain Benjamin Hornigold, sailing out of New Providence in the Bahamas. He soon distinguished himself by his strength, courage, and devil-may-care attitude. He sailed with Hornigold to engage in a plundering expedition off the coast of North America. The hunting was good, and several rich prizes were taken. After careening their ship in Virginia, the pirates sailed on the return voyage to the islands.

A merchantman flying the French flag was sighted, overhauled, and taken on the way. She was engaged in trade between the French Island of Martinique and the African coast. Well-built and fast, Teach saw the means of realizing his ambitions in this ship. He suggested to Captain Hornigold that he had demonstrated such energy and leadership as to prove he could command his own vessel. He asked Hornigold to make him captain of this prize. His request was granted, and Edward Teach was on his way to becoming a legend in the annals of piracy.

Both ships were made for New Providence. They found the town buzzing with the news of the King’s proclamation offering clemency to pirates who would promise to reform. Hornigold, now a wealthy person, has decided to accept. You might say he went far beyond the terms of the proclamation. Until his death, Hornigold devoted his energies to aiding the new governor, Woodes Rogers, in capturing other pirates.

Teach had no such ideas. He re-christened his new command the Queen Anne’s Revenge. And before long, 40 cannons thrust their ugly muzzles through the gun ports. Such firepower allowed him to attack the largest and best-armed merchant ships. It was not too long before he could prove his ship’s strength. The Great Allan, a large merchantman laden with valuable cargo, was taken near the Island of St. Vincent. After the valuables were transferred to the Queen Anne’s Revenge and the prisoners put ashore, the Great Allan was put to the torch. Edward Teach had begun his career as a pirate captain in a grand style.

The capture of this ship also allowed Teach’s crew to demonstrate their fighting ability. The news of the fate of the Great Allan spread. The Scarborough, a 30‑gun British warship, was put out to sea in search of the Queen Anne’s Revenge. Sighting the quarry, the man-of‑war closed in for the kill. Teach was ready and quite willing to trade shots with the navy vessel. The two ships exchanged broadside after broadside. After an extremely bloody battle lasting for several hours, the battleship pulled away and limped toward the nearest port in Barbados. The news that Teach had bested a warship of the Royal Navy in combat only made his name more feared than ever.

Teach was not the name that was so feared, however, for it was around this time that the pirate became better known as “Blackbeard.” It was good business for a pirate to cultivate such a name and make it as fearsome as possible. An evil reputation was a great aid in persuading prospective victims to surrender quickly with minimal resistance. With this in mind, he deliberately attempted to emphasize the evil side of his character. He was a tall man and of a powerful physique. His long, bushy, pitch-black beard gave him his name. Before any action, he would plait this beard into little pig‑tails, which he tied up with colored ribbons. Some of these braids were twisted back over his ears. And just before doing battle, he would secure several of the long, slow-burning matches used to touch off the cannon. These he would tuck under his hat, lighted, allowing them to dangle around his face, the curling wisps of smoke adding to the frightfulness of his appearance. In the belt strapped around his waist were pistols, daggers, and his cutlass. Across his hairy chest, he wore a bandoleer, or sling, in which were fixed three braces of pistols, all six of which were primed, cocked, and ready for instant firing. Indeed, Blackbeard, in his battle dress, was a most awesome sight. To the sailors of the day, he was feared almost as much as the Devil himself, and many were sure that they were kin.

Blackbeard’s reputation as an invincible terror of the seas increased considerably with his defeat of the warship. The very fact that he had dared to do battle with a warship made him a person to be much feared. After this encounter, he sailed for the Bay of Honduras, where he met Stede Bonnet. And it was the result of this meeting that Bonnet had, for several months, remained a virtual prisoner aboard the Queen Anne’s Revenge, with Blackbeard trying to comfort him by pointing out that he could now “live easy and at his pleasure,” and subsequently would not be “obliged to perform duty, but follow his own inclinations.”

The two ships, both named Revenge, sailed northward to Turniffe Island to fill their water casks. A sloop was sighted even as they lay at anchor, beating her way into the island for the same purpose. Quickly slipping his cable, Lieutenant Richards hoisted the black flag and soon overhauled the stranger. The sloop, the Adventure of Jamaica, surrendered without resistance. Her master was David Herriot, who accepted an invitation to join the pirates with the rest of his crew. Israel Hands (sometimes called Hezikiah or Basilica Hands) was placed in command of the Blackbeard and was now in command of a regular fleet of pirate ships.

After filling the water casks, they sailed again for the Bay of Honduras. Luck was with them. A Boston ship, the Protestant Caesar, and four sloops were lying at anchor. The very sight of the “Jolly Roger” (pirate flag) so frightened the crews of these vessels that they scrambled over the sides into boats and fled to the safety of the shore. The cargoes were quickly plundered. And, because the people of Boston had lately hanged several pirates, the Protestant Caesar and one of the sloops were burned.

Blackbeard’s little squadron began to haunt the sea lanes between the mainland and West Indian Islands from this time on. Several times, they were put into Cuba and sold their booty in Havana. Although these buccaneers roamed far out to sea, North Carolina became their headquarters. They used several hideouts, for continually returning to the same spot was too dangerous. Legend says that one of their retreats was up the Chowan River as far as Holiday’s Island. Probably the favorite refuge, however, was Ocracoke Inlet. Tradition indicates that a house known as “Blackbeard’s Castle” used to stand in the village, and an inlet not too far from today’s village of Ocracoke was known as “Teach’s Hole” (known today as Springer’s Point.) Here, supposedly, Blackbeard came to careen his ships.

One of the best hunting grounds in the Atlantic at this time was off the port of Charleston, South Carolina. This Port was the busiest and most important in the southern colonies. Because of the happy prospect of taking richly-laden merchant vessels, Blackbeard’s flotilla began to hover outside the entrance to the harbor, ready to pounce upon the first unwary victim that shoved its bowsprit into the open sea. One ship was taken, then another, and still another. They carried rich cargo. One ship carried 14 slaves, while another held over £6,000 in gold. Before the South Carolinians realized what was happening outside the harbor, eight or nine ships had been quickly taken. Within Charleston, all was confusion. Trade came to a standstill. Eight ships lay tied to the piers, not daring to hoist their sails.

Blackbeard chose this moment to display not only his colossal nerve but his contempt for all landlubbers in general. His medicine chest was low. Charleston was near, and the apothecary shops of that city held the drugs he needed. And he held all the trump cards. Among the prisoners taken from the captured vessels was Samuel Wragg, a Governor Johnson’s Council member. Such an important person made an excellent hostage. Lieutenant Richards of the Revenge was selected to make a demand upon the town for the medicines necessary to fill the pirate chest. In a small boat, Richards arrogantly steered into the harbor. Another man named Marks, also a captured passenger, was sent along to verify the capture of the ships and the holding of the hostages.

To Governor Johnson, Richards delivered an insolent message from Blackbeard. Unless declared the pirate captain, the town made up the necessary list of medicines, and the hostages would be killed and their heads delivered to the governor. Not only this, warned the report, but if the pirate’s demands were not fulfilled, Blackbeard threatened “to burn the ships that lay before the town and beat it about our ears.” Two days were allowed to fill the medicine chest.

The governor called his Council into an emergency session. While the demands were being debated, Richards and his companions strutted boldly about the streets of Charleston. The governor and the Council had no wish to give in to the pirates, but there was nothing else they could do. There was no warship in the harbor to protect Charleston, and the pirates could have sailed in and sacked the town with practically no opposition. Sadly, and perhaps a little embarrassed, they filled Blackbeard’s medicine chest with supplies costing between £300 and £400.

Still holding Marks hostage, Richards and his pirates returned for their ships. A sudden storm upset their boat and forced them back to shore. When they finally were able to beat their way back, the two-day deadline had expired, but Blackbeard had not yet carried out his threat to kill the hostages. The captain kept his word and released the prisoners until they had been plucked clean. All their money was taken, including Samuel Wragg’s £6,000. The better-dressed of the prisoners were stripped of their finery and sent, half-naked, back to shore. Blackbeard’s infamous crew then set their sails and gaily made for North Carolina. Behind them, they left an angry and mortified Charleston. The people of Charleston neither forgave nor forgot, as Stede Bonnet and his crew, much to their sorrow, were to discover.

Incidents such as these furnished the excitement on which Blackbeard thrived. There were days when life was dull, and the pirate captain had to find his thrills, thrills that were usually tinged with cruelty and touched by terror. Perhaps such a display was necessary to maintain discipline and keep down the frequent plots to remove him from his position of authority.

There was, for instance, one night when Teach was drinking in his cabin with Israel Hands and another member of the crew. Suddenly, without warning, Blackbeard drew two pistols, cocked them, and pointed them beneath the table. He blew out the candle. The other pirate, wiser to the ways of his captain than Hands, scurried from the cabin. Crossing his hands beneath the table, Blackbeard fired both pistols. Israel Hands received the full charge of one of the weapons in his knee, an injury that left him lame for the rest of his life. When other crew members asked the captain why he would intentionally injure a friend, he explained, “If he did not shoot one or two of them now and then, they’d forget who he was.”

He always tried to demonstrate to his men that he was superior to them in every way. Upon one occasion, they were becalmed on a flat and glassy sea. Not a whisper of a breeze wrinkled the limp sails hanging from the yardarms. The men were irritable and spoiling for a fight. The pirates broke open the rum barrels for the lack of some better amusement. Suddenly, Blackbeard, “a little flushed with drink,” leaped to his feet and shouted to his men, “Come, let us make a Hell of our own, and try how long we can bear it.” Three of the more daring crew members accepted the challenge and followed him down into the vessel’s hold. They seated themselves on the rocks used to ballast the ship. The captain shouted directions for several sulfur pots to be brought down and lighted. The hatches were closed tight. The dark hold was soon filled with swirling clouds of choking fumes. The gasping sailors cried for fresh air. Only then were the hatches thrown open, the captain “not a little pleased that he had held out the longest.” One of the sailors jokingly said, “Why, Captain, you look as if you were coming straight from the gallows.” “My lad,” roared Teach, “that’s a brilliant idea. The next time, we shall play at gallows and see who can swing longest on the string without being throttled.” No record of anyone wanting to play this game with their leader exists.

Such was the nature of the man who had humiliated the citizens of Charleston. This was the man who seemed to be continually searching for excitement. But now, a strange mood seems to have descended over the once savage beast. Now, he appeared to crave the quiet life ashore. Even so, his admirable intentions were shot through with greed and treachery.

Upon their return from Charleston, the pirate fleet had sailed into Topsail Inlet. On the pretense of careening his ships to scrape the hulls, Teach ran two of the vessels aground. And suddenly, with great generosity, he placed Major Stede Bonnet in command of the Revenge again. Then, he confided in Bonnet about his future plans. He had learned, said Blackbeard, that the king had extended his offer of pardon to all pirates who would voluntarily come in and take the oath. He declared that he planned to do this and urged the major to do the same. Bonnet left for Bath almost immediately.

Almost before he was out of sight, Blackbeard loaded all of the booty on the ship Adventure and slipped out to sea with 40 crew members. Some of the sailors who were left behind made their way overland to Philadelphia and New York. Others, fearing the wrath of their captain, hid onshore. Seventeen others who objected to Blackbeard’s methods were stranded on a lonely sandbank without food and water some 13 miles from the mainland. Bonnet later rescued this group. Scattering the crew meant a larger share of the spoils for the selected 40 men who remained with their captain.

Blackbeard outwitted Bonnet. He knew full well that the major would attempt a pursuit as soon as he discovered this treachery. He dropped hints that he was sailing for Ocracoke Inlet and then set a course for the town of Bath. Bonnet had hardly left this town before Blackbeard appeared offshore. Swaggering up to the house of Governor Charles Eden, he surrendered himself and 20 of his men, all of whom were granted the king’s pardon. The pirate seems to have been no stranger to the governor, for already there were stories that he had been paying the governor for protection.

Governor Eden arrived in the colony in 1714 and was to remain chief executive for the next eight years. Before long, it was whispered around Bath that any pirate was safe in North Carolina waters so long as he shared his loot with the governor. As one contemporary writer said, “These Proceedings show that Governors are but Men.” Tobias Knight, the governor’s secretary, member of the Council, and acting chief justice was also reported to have his finger in the pie. Others welcomed the pirate. Blackbeard himself boasted that he could be invited into any home in North Carolina.

Romance then entered the life of this arch-pirate. He bought himself a fine home, and his lavish display of fine silks, jewels, and gold dazzled the eyes of one 16-year‑old lass so that she readily consented to become his wife. The governor attended the wedding, while some reports say he performed the ceremony. Unknown to his bride, this was the pirate captain’s 14th wife. Gossip around Bath murmured that no less than 12 Mrs. Teaches were still alive in various West Indies ports. The newest Mrs. Teach, however, soon had to regret her trip to the altar. Her new husband treated her little better than a member of his crew. In fact, he behaved towards her so shamefully and with such brutality that even the former members of his crew began to protest.

Blackbeard’s life ashore was one of merrymaking and dissipation for the next few months. He made friends with the neighboring planters by bestowing upon them gifts of rum and sugar. Entertainments in his home were on a lavish scale. A pirate’s treasure would not last very long under such a strain. As his fortune thinned, so did his disposition. The former jovial host now grew sullen. Neighbors who had been guests in his home a short time earlier were now robbed when the opportunity presented itself. Ships making their way up the river were sometimes plundered and robbed. Yet, no one dared identify Teach as the culprit.

The rewards of this small-time piracy were meager. Greater riches could be found in the ocean. A call was sent out to old members of his crew to rejoin him. The eight‑gun sloop Adventure was prepared to go to sea. The respectable Mr. Teach answered that he was planning a trading expedition to the West Indies to those who asked. The pirate bridegroom then slipped down the river to the open sea, where the hunting was good. Within a few weeks, he dropped anchor again at Bath, with a large French ship as a prize, richly laden with sugar, cocoa, spices, and other merchandise.

Blackbeard’s report bordered on the ridiculous. He reported to the governor that he had found this French ship drifting at sea without sign of any human being on board. The truth was far different. He had captured two vessels flying the French flag, but the cargo of one was not worth plundering. Both crews had been placed on this prize and allowed to go their way. The ship with the richer cargo was brought back to Bath.

Governor Eden convened a Vice-Admiralty Court. Tobias Knight sat as the judge. The French vessel was then condemned as a legitimate prize, and the pirates were given permission to sell the cargo. They could have also sold the ship, but this was risky; someone might recognize it and tell the true story. The pirate captain thereupon announced that the prize was too leaky to be seaworthy, and, with the Governor’s permission, she was towed upriver from Bath and set afire. When the flames consumed everything above the waterline, the portion of the hull still afloat was sunk to conceal all remaining evidence. It was rumored around the community that the Governor had received 60 hogsheads of sugar and Tobias Knight 20 as their share of the loot.

Back to sea went the pirate, navigating up and down the coast, attacking any unwary ship that crossed his path. Frequently, he turned into one of the many rivers along the coast, sometimes to hide and sometimes to provision his sloop. Supplies were secured from one of the many plantations lining the stream’s banks. If he wanted to appear as an honest seaman, a fair trade would be made for the provisions. Otherwise, the pirates took what they wanted by force if necessary.

The Adventure cruised as far north as Pennsylvania, and on several occasions, Blackbeard and his crew boldly walked the streets of Philadelphia. This was too much for the people of that city, and Governor William Keith issued a warrant for the pirate’s arrest. By this time, however, Blackbeard had sailed southward again to the healthier environment of North Carolina.

Despite the governor’s friendship, even this colony was no longer the safe haven it had once been. Human endurance had been pushed to the limit by the insolence and insults of the pirates. Every captain who took their ship out of port was gambling on their ability to slip by the buccaneers. Something had to be done. When help came, it came from the neighboring Colony of Virginia rather than from North Carolina. Because of the valuable cargo carried in and out of Chesapeake Bay, Virginia had long been plagued by pirates. In 1717, Governor Alexander Spotswood of that province reported that sea traffic was practically at a standstill because pirates were almost constantly patrolling the ocean off the Virginia Capes. During one six‑week period, no ship dared to leave the safety of Virginia shores. Spotswood was no Eden. His activities in suppressing the buccaneers were just as vigorous as Eden’s were lax.

So, the people of North Carolina turned to the governor of Virginia rather than Eden. The colony’s “Trading People” transmitted several pleas for help to their neighbor to the north. Witnesses who signed statements or affidavits indicating the close relations between Governor Eden of North Carolina and the pirates were found.

Even with these accusations, certain legal obstacles must first be cleared away. Because Teach had accepted the king’s pardon, he was supposedly no longer a pirate. Evidence had to be secured proving he had committed other acts of piracy after accepting the pardon and taking the oath. This evidence was found in Virginia. A man named William Howard, who had served as quartermaster under Teach, was captured in the colony. Charged with serving with “one Edward Teach and other wicked and desolate persons . . .” he was brought to trial not having the “Fear of God before his eyes nor Regarding the Allegiance due to his Majesty nor the just Obedience he owed to the Laws of the Land… ” Howard broke down under questioning, and it was from his testimony that it was learned that Blackbeard and his crew had returned to a career of piracy after accepting His Majesty’s pardon. Not only that, but they had taken at least two prizes since they had resumed the profession.

Reports began to filter in from North Carolina. Blackbeard had entered Ocracoke Inlet with his latest prize. Even more disturbing was the information that the pirate had indicated that he was planning to fortify the shore of that place and develop it into something of a pirate’s refuge or haven.

At this time, two British warships were lying at anchor in the James River. One was the Pearl under Captain Gordon; the other, the Lyme, was commanded by Captain Ellis Brand. Although these men-of‑war carried the necessary firepower to blast the pirates out of the water, they were much too large and drew too much water to navigate the shallow waters of North Carolina’s sounds and inlet. Governor Spotswood was determined to dispatch an expedition to capture Blackbeard. Yet, he wanted to keep it secret and could not request the legislature for the necessary funds. Two fast and light sloops were hired with money from his own pocket. Two pilots familiar with the shoal waters of Ocracoke were also employed.

But what about a crew? Seamen were plentiful, but it would take a trained fighting crew to capture the pirate. Captains Gordon and Brand agreed to man the sloops with sailors from the Pearl and the Lyme. Sixty men were selected. Lieutenant Robert Maynard of the Pearl was given command of the larger sloop, which was nameless in the official dispatches, while the first officer of the Lyme was in charge of the smaller vessel, the Ranger. Captain Ellis Brand was given the overall command and direction of the expedition. Governor Spotswood persuaded the legislature to offer a reward for the capture of Blackbeard and his men. Even then, he did not reveal the purpose of his expedition.

Captain Brand hurried to Bath. On November 17, 1718, the two sloops quietly weighed anchor and slipped out of Chesapeake Bay into the Atlantic Ocean. A course was set for Ocracoke Inlet.

Near dusk on November 21, the Ranger steered into the inlet with its companion sloop. Blackbeard’s Adventure was anchored in open water. Maynard dropped anchor and waited for daylight to launch an attack.

The appearance of an enemy was no surprise to the pirate. Tobias Knight had thoughtfully dispatched a letter that warned of the possibility of such an expedition. Edward Teach, the terror of the seas, worried little about what the morning might bring. He feared no one. Unlike Maynard, who spent the night preparing for the next day’s struggle, Blackbeard spent most of the night carousing in his cabin with the captain of a nearby merchant vessel.

Lieutenant Maynard attacked with the sun. Small boats were put overboard. These were to explore the interval between the ships and take soundings. Maynard would take no risk of running aground. As these rowboats came within range of the Adventure, they were greeted with a round of shots. They scurried back to the protection of the sloops. Maynard ordered the smaller of his ships to slip in close to the pirates and board their ship. The larger sloop followed but soon found herself stuck hard and fast on a sandbar. Ballast was thrown overboard, and she was soon light enough to float again. By this time, the Ranger had also run aground and was now definitely out of the fight. Maynard’s sloop had to carry the fight to the enemy alone.

Blackbeard, leaping to the top of the deck cabin, shouted across the water, “You villains! And, from whence come you?”

Running up the British ensign, Maynard answered, “You may see by our colors that we are no pirates.”

The pirate captain shouted an invitation to send over a boat so that he might see who they were.

Still playing this game of words, Maynard indicated his intention of boarding the pirate sloop: “I cannot spare my boat, but I will come aboard as soon as I can with my sloop.”

Blackbeard angrily shook his empty rum cup at the sky and bellowed, “Damnation, seize my soul if I give you quarters or take any from you.”

With this, “the black Ensign with the Death’s Head” ran up to the masthead, the anchor cable cut, and sails quickly hoisted. The first pirate broadside was directed at the Ranger, whose crew was still working feverishly to re-float her from the sandbar on which she was stuck. The commanding officer and several of his seamen were instantly killed. Pulling around quickly, the next cannon blast was loosed at Maynard’s sloop. The ship was not armed with a cannon, and her men could return the fire only by popping away with muskets. The wind died down. Maynard had to get in close before the pirate cannon blasted him right out of the water. The sweeps, or heavy oars, were broken out, and the large sloop was slowly worked towards the Adventure. Another pirate broadside tore into the men at the sweeps. A number of the men were killed or badly wounded, with some reports listing as many as 21.

Maynard ordered his men below decks after a greater slaughter but instructed them to keep their pistols primed and their cutlasses ready. Only two men, a midshipman and a pilot, remained on deck, shouting information to Maynard below. Seeing his adversary’s empty deck, Blackbeard worked toward Maynard’s vessel. As the pirate craft came up alongside the sloop, homemade grenades, boxes filled with powder, small shot, and scrap iron, with fuses smoking, were tossed into Maynard’s ship. The explosion did minor damage. Through the smoke clouds, the pirates could see only a few men running about the vessel’s decks. Blackbeard called to his men that their enemies were all dead except three or four and shouted, “Let us jump on board and cut those that are alive to pieces.”

Maynard and his men burst from the hold as the pirates scrambled over the gunwales. All was confusion. Amidst the shouts, the cracking of pistol shots, the clatter of swinging sabers, and the cries of wounded men, Blackbeard and Maynard met face to face. Both fired their pistols at almost the same instant. Blackbeard missed. The ball from Maynard’s weapon plunged into the pirate’s body. It failed to stop him and hardly slowed him down. Both men began to swing their heavy swords. A mighty sweep of Blackbeard’s weapon snapped Maynard’s cutlass like a twig. The mighty arm drew back to deliver the death blow. Just in the nick of time, one of Maynard’s men stepped in and slashed the throat of the pirate. Maynard received a blow across the knuckles. Still, the powerful Blackbeard fought on. He pulled another pistol from his belt. While still in the act of cocking the weapon, he suddenly toppled over dead upon the deck. Twenty-five wounds, five of which were pistol balls, had finally sapped the life from his magnificent body. Edward Teach had died just as hard as he had lived.

With over half the Adventure’s crew killed and their leader lying motionless, the remaining pirates threw down their weapons and cried for mercy. Several made their escape by leaping over the side and swimming ashore.

Another struggle had been going on down in the hold of the Adventure. One of the crew members, a black man named Caesar, had been ordered to station himself at the door leading into the powder magazine. If Maynard’s men could take the ship, Blackbeard had ordered Caesar to blow it up. A planter seized the night before and held prisoner during the fight overpowered him before he could set off the explosives.

Nine pirates lay dead, sprawled on the deck of Maynard’s sloop near their captain’s body. All nine of the survivors were wounded. Of Maynard’s crew, ten had been killed. Another 24 were wounded, one of whom later died. A search of Blackbeard’s belongings revealed several interesting items. There were several letters, including several from prominent New York merchants. There was another, which began with “My Friend” and which was signed with “T. Knight.” This communication from the governor’s secretary contained a veiled warning and indicated that Governor Eden would welcome a visit from the pirate. There was also a very revealing account book of the disposition of the loot taken by Blackbeard.

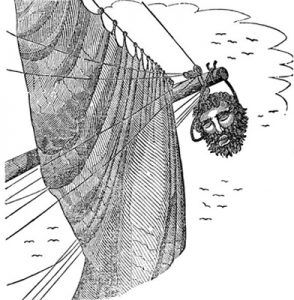

After searching the pirate’s belongings, Maynard severed Blackbeard’s head from the shattered body. This grisly trophy was then suspended beneath the bowsprit of the sloop. Sails were hoisted, and the course was steered for Bath. Here, the letter from Knight to Blackbeard was delivered to Captain Brand. The captain had already contacted Maurice Moore and Captain Jeremiah Vail, who had shown him Tobias Knight’s barn, where much of the pirate booty had been stored. When Brand accused Knight of having these goods, the secretary professed that he knew nothing of what he was talking about. He began to weaken when he was shown the pirate’s account book. When Governor Eden was shown the evidence, he could do nothing to protect his secretary and issued the necessary orders permitting a search of the barn. 140 barrels of cocoa and one cask of sugar were concealed under the hay. Knight then changed his pretense and said that he had known the loot was there, but he had merely been storing the goods there for Blackbeard, who he had thought was now a respectable tradesman. It was even suggested that some of the articles found in Knight’s barn belonged to Governor Eden. Nevertheless, all were removed and placed aboard the ships under Brand’s command.

Six other pirates, including the lame Israel Hands, were also picked up in Bath. Then, with the pirate booty on board and Blackbeard’s head still dangling from the sloop’s bowsprit, Maynard and Brand sailed back to Virginia.

This incident led to quite a dispute between the governments of North Carolina and Virginia. Governor Eden, especially after discovering that his share of the pirate goods had been taken away along with that of Knight, lodged a vigorous protest with Governor Spotswood. He justified his objections because Spotswood had exceeded his authority in the invasion of North Carolina waters. He demands that the captured pirates be returned to North Carolina for trial. Yet he had made no such demands upon Governor Johnson of South Carolina, who, in like manner, had been responsible for capturing Stede Bonnet in North Carolina waters.

The evidence showing Knight’s connections with the pirates began to grow. Israel Hands, desperately trying to save himself from the gallows, supplied much of the testimony that implicated Knight with Blackbeard. Maurice Moore, Edward Moseley, and Jeremiah Vail decided to furnish additional evidence in an attempt to destroy any likelihood of North Carolina becoming a pirate haven again. They tried to examine the records. When this was denied them, they decided to take matters into their own hands. On December 27, 1718, they broke into the home of John Lovick, deputy-secretary, at Sandy Point. To have sufficient time for a complete examination of the records, they nailed up the room and spent the next 24 hours shuffling through the papers. Governor Eden, declaring this to be an “unlawful and improper action,” sent a large posse to arrest them, which led Moseley to make the bitter observation that “the governor could find enough men to arrest peaceable citizens, but none to arrest thieves and robbers.”

Governor Eden could not afford to ignore the charges piling up against his secretary, especially after Spotswood sent him a copy of the testimony of Israel Hands. On May 27, 1719, Knight was called before the Governor’s Council to defend his past actions. His letter to Teach was entered as evidence, and the handwriting was compared with other documents prepared by the secretary. Despite this proof, Knight still denied that either he or Governor Eden had anything to do with the pirate captain. The Council, which seems to have been under the influence of the governor, pictured Knight as “a good and faithful officer,” declaring the evidence against him to be “false and malicious,” and handed down a verdict of “not guilty.”

Moseley and Moore did not get off so easily. Both were brought to trial before the General Court and found guilty. Moore received a fine of only £5, but Moseley, who had been most critical of the Governor’s actions, was the victim of more severe punishment. He was not convicted for breaking into Lovick’s house to examine the records but for speaking “scandalous words” against the governor. He had been so bold as to criticize Eden for not doing anything about Teach. His fine was set at £100, and he was forbidden to hold any public office for three years.

Meanwhile, most of Teach’s crew had met the same fate as their captain. The courts of Virginia had found them guilty of piracy. Thirteen of their number met their end swinging beneath the gallows. Only two escaped the noose. Samuel Odell, who had received over 70 wounds in the fight with Maynard’s men, was one. He proved that he had been forcibly taken from a trading vessel only the night before the battle and had been forced to join Blackbeard’s crew. The other was Israel Hands, whose lameness at his captain’s hands may have been responsible for some sympathy from the judges. He was convicted and sentenced to hang, but while still awaiting execution, received word that the King’s pardon for pirates had been extended. His request that he be allowed to take advantage of this was granted.

So ends the saga of Blackbeard, the “most ferocious pirate of them all.”

By Hugh F. Rankin, The Pirates of Colonial North Carolina, North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, 1960. Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated April 2024.

Also See:

Pirates – Renegades of the Sea

Privateers in the American Revolution

This article was excerpted from The Pirates of Colonial North Carolina, a publication of the Historical Publications Section, Division of Historical Resources, Office of Archives and History, North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources. The author, Hugh F. Rankin (1913‑1989), was a noted historian of colonial America and the American Revolution and a history professor at Tulane University from 1957 to 1983. He was the author or co-author of well over a dozen books on historical subjects and many journal articles. This booklet is in the public domain today as its copyright was not renewed. Though the context of the article has not changed, some minor editing has occurred.