The area surrounding Nelson and Eldorado Canyon in Nevada was first home to the ancient Ancient Puebloan Indians and later the Paiute and Mojave tribes. Living peacefully for hundreds of years, the Indians were intruded upon in 1775 when the Spaniards arrived in the canyon in their constant quest for gold. Founding a small settlement at the mouth of the Colorado River, they called it Eldorado. However, these early Spaniards somehow missed the rich gold veins just beneath the canyon’s flanks, finding silver instead. They soon found that the silver was not in high enough quantities to justify their operations and moved on.

Seventy-five years later, in the 1850s, a new breed of prospectors began sluicing the many streams feeding into the Colorado River.

For a few years, the miners could keep their gold find a relative secret due to the area’s remoteness. However, this all changed in 1858 when the first steamboats began to make their way up the Colorado River from Yuma, Arizona. Before long, word spread, and miners began to flood the area.

By 1861, miners had discovered the Salvage Vein about five miles up from the Colorado River. The rich, vertically stacked ribbon of gold ran through a steep ridge along one side of the canyon. The miners began at the top of a high hill, cutting down into the vein. Before long, several of the miners formed the Techatticup Mine, supposedly through a series of shady dealings. The name derives from the Paiute Indian word for hungry, a term often heard by early settlers from the starving Indians inhabiting the dry hills. The Techatticup Mine was once owned by Senator George Hearst of California, father of William Randolph Hearst of publishing fame.

Before long, the Nelson District was dotted with several mines, including the Gettysburg, Duncan, Solar, Rand, Wall Street, Swabe, and Golden Empire Mines, in what was to become one of the earliest and richest mining districts in Nevada. The Techatticup Mine, along with the Gettysburg, was the first mine in Nevada to be worked by white men.

Many prospectors who found their way to the goldfield were reportedly Civil War deserters, and disagreements and gunfights over gold and women became commonplace. Greed, claim-jumping, and vigilante justice fueled the fire. Meanwhile, the Techatticup Mine was amid feuds over ownership, management, and labor disputes, soon earning it a notorious reputation. At one point, the killings in the rowdy canyon, called home to as many as 500 miners, became an almost daily event where even lawmen refused to enter.

Despite the sinister reputation of the mine, the Techatticup was to become the most successful in the area, mining millions of dollars in gold, silver, copper, and lead throughout the years. For the next 70 years, Techatticup Mine miners dug deeper into the hard rock, working with picks and shovels in chambers lit by candles.

As the gold played out in one tunnel, they would carve a new one just beneath it using blasting powder and then drag out the broken rocks to be pulverized and treated with cyanide to separate out the gold. Over the years, the miners excavated tiers of a dozen tunnels, the lowest of which could be reached by a long tunnel cut into the hillside some 500 feet below the upper entrance. The temperature remained constant in the tunnels at around 70 degrees, and it is said that some of the miners slept inside their workplaces to escape the desert heat.

The Techatticup Mine, along with dozens of others, engendered several settlements, including Nelson and Eldorado, at the river’s edge. As the ore was extracted from the many area mines, it was transported to Nelson’s Landing along the Colorado River and shipped by steamboat to Yuma, Arizona, for overland shipment to San Francisco, California. The river also served as the primary source of much-needed supplies for the camps along the canyon.

In 1864, when the area was still a part of Arizona, the territory’s first stamp mill was built near the steamboat landing. The 10-stamp, steam-driven mill then processed the ore from the area mines before shipping it to Yuma.

The lawlessness continued as factions of Northern and Southern sympathizers developed among the miners during the Civil War. The strife and bitterness split the workers into two camps, severely hindering mine and mill production. Before long, Federal troops stationed downriver had to be brought in by steamboat to break up the factions before more bloodshed occurred. The lawlessness worsened after the area became part of Nevada when the nearest law officials were in Hiko, Nevada, some 300 miles away. Finally, a military post was established in Eldorado Canyon in 1867 to protect the steamboat traffic and to keep an eye on the local Indians who were beginning to raid the canyon.

By 1883, a railhead was developed at Needles, California, and the long riverboat shipments to Yuma were rerouted to Needles, where the ore was offloaded. Eventually, better overland routes eliminated the need for steamboats.

Posse, who recovered Queho’s remains, stands at the mouth of his cave hideout. From left, Clarke Kenyon, Frank Wait, and Art Schroeder.

In addition to the canyon’s numerous rowdy miners, two of Nevada’s most famous renegade Indians lived in Eldorado Canyon, the first of which, a man named Arvote, was said to have killed five area settlers. At about the same time, a Cocopah Indian named Queho was terrorizing the area and was reportedly Nevada’s first serial killer. He was said to have murdered 23 people in the early 1900s. The last person Queho killed was Maude Douglas near the Techatticup Mine in 1919. Having already become Nevada’s Number 1 Public Enemy, the Indian was relentlessly pursued by sheriff’s posses but was never captured. What was thought to have been his remains were finally found in a cave in Eldorado Canyon in 1940.

In the early 1900s, Nelson’s Landing was one of the largest ports on the Colorado River and became even more important in the 1920s for two reasons.

The first was prohibition, enacted on January 16, 1920. Prohibition was strictly enforced on the Arizona side of the river in Mohave County, and moonshine sold for as much as $50.00 a gallon. However, in Clark County on the Nevada side, prohibition was not enforced, and homemade liquor sold for as low as $1.00 a gallon. This created a brisk trade along the river as bootleggers ran their white lightning into Arizona.

The second was the preliminary work required to build the Hoover Dam. Dozens of surveyors operated small boats from Nelson’s Landing, while many others were ferried across the river to complete their work. When the dam was completed, the area became one of the first main tourist sites as visitors were guided to the best fishing areas and taken on tours of the dam. Before long, Nelson’s Landing was a resort where boats, bait, gasoline, food, and cabins were provided.

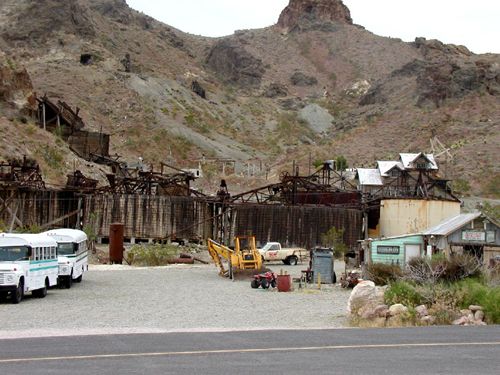

The Techatticup Mine remained active until about 1945, producing more than 2.5 million dollars worth of gold, silver, copper, and lead. After that, it sat abandoned for almost five decades. The town of Nelson dwindled quickly, leaving little more than the remains of mine works and tailings among the scorpions and rattlesnakes.

Following the completion of Davis Dam in the mid-1950s, Lake Mohave began to fill up, drowning the old stamp mill site, the steamboat landing, and the remains of the Eldorado Camp.

The Nelson District yielded over 500 million dollars in ore in its almost 100 years of mining.

A tour of Eldorado Canyon begins by accessing Nelson Road (Nevada Highway 165) from I-95 south of Boulder City. Traveling southeast, the highway gradually climbs through about 11 miles of desert hills before reaching the old mining community of Nelson, Nevada. This part of the drive will provide numerous picturesque views of desert wildflowers during the spring. Nelson is entirely surrounded by Bureau of Land Management property, where you might also see bighorn sheep and wild burros roaming among the hillsides.

One of the many buildings restored/recreated by Tony and Bobbie Werly, that now serves as a museum, by Kathy Alexander.

Today, Nelson is all but a ghost town with a population of just about twenty people. With no open businesses, the town marks its past with a few weathered sheds, small shacks with corrugated metal siding, and rusting machinery parts. Those few remaining residents live in a few modern buildings and mobile homes. On a hillside above Nelson is a small, overgrown cemetery, and though it has some fairly recent graves, they can barely be seen through the brush. Though it’s hard to imagine today, in the 1880s, Nelson and the ten-mile Eldorado Canyon was called home to more people than the entire Las Vegas valley.

As you leave Nelson, the road begins a twisting drive through the canyon, providing dramatic views of rugged rock walls and stone formations, pocked with holes and tailings from its old mining days.

Clearing the rubble from the mine tunnels, stabilizing ramps and ladders, and installing electric lights and emergency phones, the mine soon opened for guided tours. The above and below-ground guided mining tour lasts about one hour, taking visitors 500 feet into the mine. On this tour, you will receive the history of the mine, Nelson’s landing, and the area’s turbulent past. Mine tours require a minimum of four people (which can be combined with another group), and reservations are recommended.

Over the last decade, the couple has also restored and preserved several buildings at the mine site. Across from the mine sits a historic 1861 building that serves as a museum for the area and the Techatticup Mine.

Here, you will see a display of old photographs, tools, and other mining memorabilia. Tony and Bobbie also provide river tours and rent kayaks and canoes for use on the nearby Colorado River. Reservations for river tours are required.

The Techatticup Mine has been the set of two movies. The first, Breakdown, with Kurt Russell and Kathleen Quinlan, was released in 1997 and several artifacts from the movie can be seen at the site. Several years later, the movie 3000 Miles to Graceland was released in 2001, parts of which were filmed at the mine site. This movie, again with Kurt Russell, as well as an all-star cast including Kevin Costner, Courtney Cox, Christian Slater, and David Arquette, shot several scenes here, including the scene where the Lucky Strike gas station blows up. Props from the movie, including the crashed airplane, can still be seen at the site.

During the mining heydays, prospectors would build a shack in which to live, using whatever was available from Kathy Alexander.

You will come to the infamous Techatticup Mine within just a few miles. After being abandoned for five decades, Tony and Bobbie Werly purchased the mine and 51 acres of surrounding property and recreated the buildings. Before purchasing the mine acreage, the pair operated a river adventure outfit in nearby Boulder City.

Beyond Techatticup, the road continues to wind its way to the Colorado River, which opens up to panoramic views across Lake Mohave and into Arizona. On the river below once stood Nelson’s landing, long gone today. Numerous old roads angle down toward the lake, where the National Park Service administers much of the area. Be aware that severe penalties for off-roading in National Park areas can be levied.

If you travel the outlying land, be cautious as many open mines and ventilation shafts exist. Though most of the mines in the district are no longer active, the majority are on private property and are so posted. Respect these no-trespassing signs, as reports show that local landowners are quick to prosecute trespassers.

To get to Eldorado Canyon, follow I-95 south of Boulder City, which is 13 miles to SR 165. Turn left on SR 165 (Nelson Road) for about 11 miles to Nelson. Continuing from Nelson, the Techatticup Mine is just a few more miles down the winding road, and a few miles beyond that is Lake Mohave.

Update: It’s been over a decade since we have been here. We recommend calling ahead to make sure they are available. We also recommend checking the latest reviews on Trip Advisor HERE.

One of the many buildings restored/recreated by Tony and Bobbie Werly, that now serves as a museum, by Kathy Alexander.

Contact Information:

Eldorado Canyon Mine Tours

Highway 165 between Nelson, Nevada, and the Colorado River

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated May 2024.

Also See:

Queho – Renegade Indian Outlaw or Scapegoat?