Stagecoach

by Daniel R. Seligman

The Marysville-to-Sacramento stagecoach run on November 14, 1858 didn’t exactly have an auspicious beginning. J. Stinchfield, driver for Fowler & Company, was unceremoniously knocked down and kicked by California Stage Company Road Agent Montgomery before he even climbed aboard his vehicle. Then Montgomery’s driver, Oscar Case, announced his intention to follow Stinchfield in his own vehicle, ominously leaving about two hours later than his usual departure time. Case drove a heavy Troy coach, Stinchfield a lighter covered wagon and carried several passengers. On the road to Sacramento, Case made a concerted effort to harass the Fowler & Company stage, continually moving ahead of Stinchfield and abruptly stopping his own team; when Stinchfield tried to pass, Case again moved in front of him. Not content with merely obstructing the other stage, Case threw firecrackers at Stinchfield’s horses and repeatedly attempted to drive the lighter vehicle off the road. At one point, Case actually ran his vehicle into the lighter coach, injuring one of the horses, causing the passengers to jump out, and hurting one of them, though not seriously.

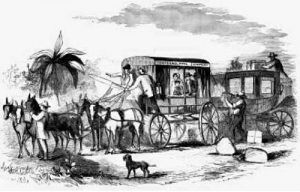

Light stagecoach

Stagecoach travel in the 19th century was anything but luxurious. The hapless passenger could expect an uncomfortable ride over rough terrain with very little to dampen up-and-down or side-to side motion. He – or, indeed, she–would often share inadequate space with fellow passengers of uncertain morals, dubious intentions, and varying commitments to personal hygiene. There was little insulation from heat, cold, precipitation, dust or insects. Food at the stations could be of uncertain quality and questionable origin. Horses were often skittish and temperamental, vehicle accidents occurred occasionally, stage robbers found tempting targets in lone vehicles traveling remote terrain, and there was always the possibility of an Indian attack. The experienced passenger was at least aware of these hazards before embarking on a journey. However, no one on the Fowler & Company Marysville-to-Sacramento coach that morning anticipated an experience that had more in common with the chariot race in Ben Hur than a journey by stage (never mind that it would be fully two decades before Lew Wallace’s classic would be offered by Harper and Brothers to an enthusiastic public).

The California Stage Company was a large, well-funded joint stock association organized from a number of competing enterprises largely through the efforts of entrepreneur and stagecoach pioneer James Birch. Fowler & Company was a small enterprise running a competing line between Marysville and Sacramento. Considered something of an upstart, the smaller company faced a David-and-Goliath stand-off with its larger and better funded competitor.

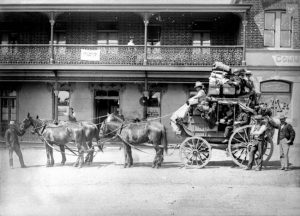

Sacramento, California 1866

Both stages halted at the stagecoach stop at Twelve Mile House, where Case threatened Stinchfield’s passengers, predicting that if they did not leave the Fowler & Company coach they would be dead before they reached Sacramento. Passenger O. Ames, having borrowed a double-barreled shotgun, warned Case that he would defend himself if Case placed his life in danger. In a subsequent exchange, passenger L.H. Ruby attempted to dissuade Case from his reckless course of action. Ruby testified at Ames’ trial that Case claimed

he was paid to do it; to run off the Opposition, break up the coaches, raise the devil generally, and show them what opposition was…

The relentless punishment continued beyond Twelve Mile House, then stopped abruptly when Stinchfield drove off the road and across a field and the heavier vehicle briefly disappeared, only to resume when Case returned with fresh horses. A reinvigorated Case forced a second collision and proceeded to whip Stinchfield’s horses several times, run his horses against Stinchfield’s, and break two spokes of a hind wheel. At this point, the coaches had locked wheels. Stinchfield — not at all surprisingly — was having a hard time controlling his horses in the face of Case’s harassment. Passenger Ames, riding outside next to the driver and close to Case, repeatedly shouted to Case to desist and allow him to get off, striking Case several times with the gun, to no avail. Finally, near Nicolaus, he discharged the shotgun, seriously wounding Case in the back, the stages separated and Ames was able to jump to the ground.

Case made a half-hearted attempt to pursue Ames, but then directed his coach toward Nicolaus. Unable to go far, he dropped to the ground where he was found by two men on horseback who obtained a buggy and transported the wounded man into the town.

Ames was arrested and tried at Nicolaus, where Justice Hart declared that Ames had acted in self-defense and summarily released him on November 26. Case died of his wounds on December 23 at the Nicolaus home of J.R. Dickey, one of the men who had found him.

Perilous stagecoach trail in California by Detroit Photographic, 1899.

Unbridled economic competition was a hallmark of late 19th-century America. While closely associated with large and heavy industries like railroads and steel, the economic doctrines of the 19th century were applied in other areas as well. In particular, the stagecoach companies that transported people and valuables where there were no railroad tracks were subject to similar motivations and employed correspondingly bold, risky, and sometimes questionable tactics. Nowhere was this truer than in gold rush era California, where stagecoach companies were occasionally capable of practices that were as dangerous as they were unscrupulous.

Stinchfield’s abuse at the hands of the agent preceding the stage run, Case’s use of a heavy vehicle, the ready availability of a fresh team of horses and Case’s remarks to Ruby all suggest that Case was carrying out company policy, however zealously, rather than acting on his own. Indeed, one Pony King stated in an unrelated trial the day before Ames’ that as an employee of the California Stage Company he was discharged when he refused to perform the same kind of aggressive driving as Oscar Case.

Barlow & Sanderson Stage Coach.

Such reckless competitive behavior was not new. A year earlier, the Sacramento Daily Union reported a Sunday morning race through Sacramento between two stagecoaches, one owned by the California Stage Company and driven by C. Cunningham and the other belonging to “the opposite line between this city and Marysville,” and driven by G. Ingalls:

It seemed, in fact, not only to be the desire of the drivers to pass each other on the ‘home stretch,’ but to run into or head off the opposing coach, regardless, apparently of the lives or limbs of passengers who crowded such, or of persons passing along or crossing the streets, of whom there were unusually many, it being about the time for the commencement of service at the various churches.

In his testimony before Justice Hart, Stinchfield even suggests that Fowler & Company might have been taking precautions against the known practices of their large competitor and Ames’ presence might have been specifically

for the purpose of fighting off the California Stage Company’s coach; he did not pay his fare; he was on the inside until after the first occurrence, and afterwards rode on the outside all the rest of the way…

We can see in this incident, called “An Unfortunate Affair” by the Sacramento Daily Union, a set of mores in wide acceptance in the 19th century carried to a dangerous and, indeed, fatal extreme by short-sighted and irresponsible policies on the part of the California Stage Company. One might question the mental health of Oscar Case, but it seems clear that the lion’s share of responsibility lies with the policies of the California Stage Company, reckless even by the rough-and-ready standards of the 19th century. Case was undoubtedly overly enthusiastic in carrying out the wishes of his employers, but the evidence suggests that such aggressive behavior was sanctioned and even encouraged.

©Daniel R. Seligman, for Legends of America, September 2024.

Author Daniel R. Seligman

About the Author: Daniel is a retired computer engineer from Massachusetts with a lifelong interest in the American West. He teaches seminars on western gunslingers and has authored a number of articles on Western history in various publications, including:

- Getting Away With Murder, Legends of America, March 2024

- These Two Highwaymen Battled for the Title of World’s Best Stagecoach Robber, Wild West, Autumn 2023, 50-55

- How to Rob a Stagecoach, Wild West, Autumn 2023, 20-21

- Mary Jane Simpson – The Lady and the Mule, Legends of America, January 3, 2023

- Charles Waggoner – Colorado Robin Hood, Legends of America, November 14, 2022

- Scouts of the Prairie: A Glorious Disaster, Legends of America, November 7, 2022

- Going for Gold: How the Confederacy Hatched an Audacious Plan to Finance Their War, America’s Civil War, July 28, 2022

- Tracking the White Apache, Wild West, October 2021, 44-49

- King of the Tulares, Wild West, April 2021, 58-63

- Annie Oakley’s Gaffe…Or Was It?, Wild West History Association Journal, September 2019, 69-73

- Rough and Ready, Wild West, October 2019, 44-49

- Bound and Determined, Wild West, August 2018, 46-51

- This Scout Lived with the Enemy, Wild West, August 2018, 22-23

- Western Stagecoach Robberies: A Statistical Analysis, Wild West History Association Journal, December 2017, 23-27

- Evolution of a Mountain Man, Wild West, October 2017, 58-63,

- The Greatest of Confidence Men, True West, June 2015, 40-41

- The Flawed Gentleman Bandit, True West, December 2013, 32-35

- Frank Butler, Much Maligned Husband, True West, March 2013, 44

References:

- Daily Alta California, 16 November 1858, 18 November 1858, 1 December 1858, 5 January 1859

- Daily National Democrat, 16 November 1858, 28 November 1858

- Red Bluff Beacon, 17 November 1858, 29 December 1858

- Sacramento Daily Union, 16 November 1857, 15 November 1858, 16 November 1858, 17 November 1858, 29 November 1858, 24 December 1858, 25 December 1858

- Gregory Michno, Those Classic Hollywood Stagecoach Chases Were More Fact Than Fiction http://www.historynet.com/stagecoach-attacks-roll-em.htm

- William B. Secrest, California Feuds, Vengeance, Vendettas and Violence on the Old West Coast, 2005

- Cheryl Anne Stapp, The Stagecoach in Northern California, Rough Rides, Gold Camps and Daring Drivers, 2014

- Lew Wallace, Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ, 1880

Also See:

Stagecoaches of the American West