Voyageurs

Voyageurs were French Canadians who engaged in the transporting of furs by canoe during the fur trade years. Voyageur is a French word meaning “traveler.” From the beginning of the fur trade in the 1680s until the late 1870s, the voyageurs were the blue-collar workers of the Montreal fur trade. At their height in the 1810s, they numbered as many as 3,000 men. Hired from farms and villages of the St. Lawrence Valley, most spoke French and generally could not read or write. These men agreed to work for several years in exchange for pay, equipment, clothing, and “room and board.” Most voyageurs would start working in their early twenties and continue working into their sixties. Sometimes being a voyageur was a family tradition.

Hard-working, tough and brave voyageurs provided the power to move the canoes forward, paddling at a rate of 40-60 strokes per minute, often 16-18 hours a day. They were also required to carry a minimum of 180 pounds on their backs, as both trade goods and furs were placed into standard weight bundles of 90 pounds each, and each voyageur was required to carry two bundles, though some carried even more. Twelve beaver hides paid the wages for a common voyageur for the year.

The voyageurs were considered legendary, especially in French Canada, where they were considered heroes and celebrated in folklore and music. However, despite their fame, their lives were not nearly as glorious as folk tales make it out to be.

Danger was at every turn for the voyageur, not just because of exposure to outdoor living but also because of the rough work. Hernias were common and frequently caused death. Other physical ailments included broken limbs, compressed spine, and rheumatism. Drowning was common and the black flies and mosquitoes were kept away from the sleeping men by a smudge fire that often caused respiratory, sinus, and eye problems.

There were two classes of voyageurs — mangeur de lard, or “pork eaters,” and hivernants, or “winterers.” The first class, dismissively called “pork eaters” because of their daily diet of salt pork and dried peas, were unskilled young men that carried trade goods and supplies to the rendezvous posts, such as Grand Portage, Minnesota, where they were exchanged for furs. The 1,200-mile Montreal to Grand Portage trip took six to eight weeks.

Hivernants were the wintering men and considered themselves superior to the “pork eaters.” These seasoned voyageurs paddled the bourgeois (traders), clerks, and the trade goods into the interior, then spent the winter helping with the trading. In the spring, they paddled canoes and bourgeois back to the inland headquarters for the rendezvous. Wintering men not only received clothing and blankets as part of their contract, but they were also issued credit in the “company store.” They were also given goods they could trade with the natives directly.

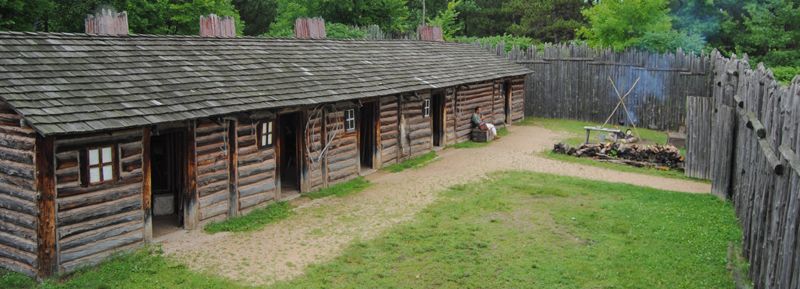

Reconstructed North West Trading Post near Pine City, Minnesota by Kathy Alexander.

In 1805, the voyageurs were described by François Victor Malhiot:

“Voyageurs were almost human paddling machines. They could paddle at speeds of six miles per hour for 12 to 15 hours a day. They sang to maintain the momentum and break the monotony of paddling for hours on end. Colorful and lively characters, they were also carried all the cargo and canoes along the portage. They built the wintering posts. They cut firewood to keep everyone warm during the long winter months. They planted gardens and traveled back and forth carrying mail, information, food, and furs. My people have not had a day’s rest since my arrival here last autumn. Of all the men who may be in the upper county I do not think there are any who worked as hard as mine: a house 20 feet square of logs, placed one on the other made by four men; 70 cords of fire-wood chopped; pickets sawn for a fort; a bastion covered; a clearing made for sowing eight kegs of potatoes, and all the journeys made here and there!”

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated November 2022.

Also See:

Grand Portage National Monument, Minnesota