By Randall Parrish in 1907

Sufferings of the Trappers

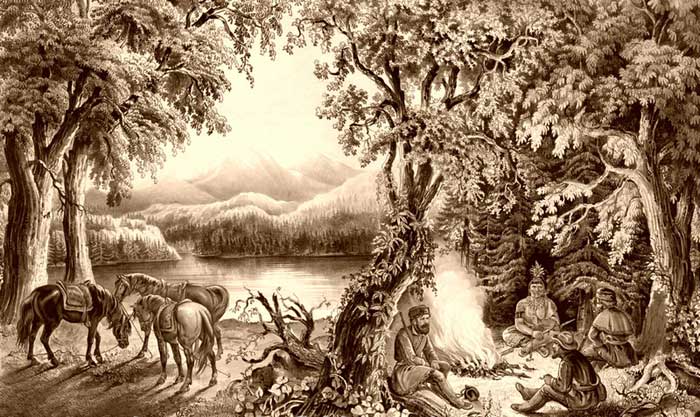

The fur trade history is filled with stories of adventure, daring, and savage warfare. What the hardy trappers suffered, isolated in the wilderness, battling constantly against wild beasts and wild men, can never be known. The majority died in the silence of remote regions; their names are long since forgotten, the heroism of their last fight untold. The records of the great fur companies alone contain brief mentions of such incidents that were worthy of being written down.

These generally occurred in the great mountains, where the trappers made rendezvous and spent most of their lives.

The disastrous Battle of Pierre’s Hole, the heroic exploration of Utah, and the first advance to California are all full of dramatic incidents. However, but the occurrences took place too far westward for the scope of this present work.

After the first years of exploration and some beaver trapping along the streams, the Great Plains were used merely as a crossing from the region of civilization to the far more profitable mountain region beyond. Up the Missouri River by boat or along the valley of the Platte River on foot, the hunters passed, alone or in companies, their destination those great ranges beyond. No doubt much hardship, adventure, and Indian fighting marked those long prairie miles, but they were not of sufficient interest to be recorded in the prosaic journals of the fur companies.

The Escape of Hugh Glass

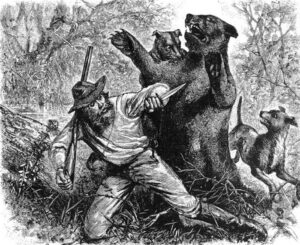

The miraculous escape of Hugh Glass well pictures the endurance and suffering of these men. Glass was connected with Andrew Henry’s party in the expedition to the Yellowstone River. While he was out hunting somewhere along the Grand River, a grizzly bear dashed out of a thicket, threw him to the earth, tore out a mouthful of his flesh, and, turning, gave it to her cubs. Glass sought to escape, but instantly she was again upon him. She seized him by the shoulder and inflicted dangerous wounds on his hands and arms. At this moment, some of his companions arrived and killed the bear. Although still alive, Glass was so terribly mangled that he was not believed to survive. They were in hostile Indian country, and it was necessary that the party should proceed without delay. Finally, Major Henry, by offering a reward, induced two of the men to remain with Glass while the others pressed forward. One of the two was John S. Fitzgerald, and the other, a mere boy, was James Bridger, later a famous trapper himself. They remained with the wounded hunter for five days. Then, despairing of his recovery, yet seeing no prospect of immediate death, they left him to his fate, taking his rifle and all accouterments with them. When they reached the main party, they reported him dead.

But Glass was not dead. Reviving, he crawled to a spring. Close beside it, he found wild cherries and buffalo berries on which he lived, slowly recovering his strength until, at last, he ventured to strike out on his long and lonely journey. His objective point was Fort Kiowa, on the Missouri River, 100 miles away. He started with hardly strength enough to drag one limb after the other, with no provisions or means of securing any, and in a hostile country where he would be the helpless victim of any straying Indian. But the love of life and a growing desire for revenge on those who had deserted him urged him to the effort. Fortune seemed with him. He came to where wolves were attacking a buffalo calf. He let them kill it and then, frightening them away, appropriated the meat, eating as best he could without either knife or fire. Bearing all he could with him, he pushed resolutely forward and, after great distress and hardship, finally reached Fort Kiowa in present-day South Dakota.

Grizzly Bear

Before his wounds had entirely healed, Glass was again in the field, starting east with a party of trappers bound down the Missouri River. When nearing the Mandan villages, he decided to walk across where the river made a bend. Here, luck was with him as Arikara Indians attacked the boats, and all those on board were killed.

Glass, too feeble to fight, had a narrow escape and was taken by friendly Mandan Indians to Tilton’s Fort. His purpose then was vengeance on those two who had deserted him in the mountains. Thus inspired, he left Tilton’s the same night, plunged into the wilderness, traveled alone for 38 days through hostile Indian country, and finally reached Fort Henry at the mouth of the Big Horn River in present-day Montana. Here, he discovered that the men he sought had gone east. Still seeking them, he accepted an opportunity to carry a dispatch to Fort Atkinson, Nebraska.

Adventures of Four Trappers

Four men started with Glass, leaving the Big Horn River on February 28, 1824. They went on foot, first into the valley of the Powder River and then across the divide into the valley of the Platte River. They made skinboats and floated down the stream until they got beyond the foothills onto the open prairie.

Suddenly, they ran into a band of Arikara, with whom they attempted to hold council. However, the Indians made a treacherous attack and killed two of the men, but, almost by a miracle, Glass managed to get away, although he lost all his equipment except a knife and a flint. He struck out again alone for the nearest post, Kiowa. It was at a season when buffalo calves were young, so he had plenty of meat, and his flint gave him fire. In 15 days of travel, he made the fort and, at the very first opportunity, went down the river again. This time, he safely reached Fort Atkinson in June 1824. His desire for revenge had apparently ceased, as he made no further effort to discover those who had deserted him. Indians finally killed Glass on the Yellowstone River in 1832.

Another pathetic incident in the wilderness illustrates the life these men lead. Six hundred and sixteen miles from Independence, Missouri, on what was later the Oregon Trail, was a landmark known as Scott’s Bluff in present-day Nebraska. The name arose from one of the most melancholy happenings in the history of the fur trade. A trapper party descended the Platte River in canoes when their boats were upset in some rapids, and all their supplies and powder were lost. Their plight was desperate and rendered more so by the serious illness of one of their members named Hiram Scott. While scarcely knowing what to do, they came upon a fresh trail of a party of white men leading down the river. Anxious to overtake this party and Scott unable to move, they deliberately deserted him to his fate, reporting later that he had died.

A year later, the man’s skeleton was discovered beside these bluffs, proving that the wretched sufferer had crawled more than 40 miles before finally surrendering to the inevitable and sinking into merciful death. The death of Jedediah S. Smith, who experienced several remarkable adventures while exploring a route to California, was one of the tragedies of the Plains. Smith was, in many respects, a remarkable, deeply religious man with undaunted courage and untiring energy. He enlisted in the fur trade when a mere boy and, at 17, won distinction among these hardy men in the Arikara War. After William Ashley’s retreat, Smith carried dispatches to Fort Henry on the Yellowstone River, a mission of great peril.

The remainder of his life was spent in the wilderness, where he became a recognized leader. In 1831, Smith, in connection with his old fur partners, David Jackson and the Santa Fe trade, secured an outfit with 20 wagons and 80 men in Missouri and started out through Kansas. Being veterans of the Plains, they felt no doubt of getting through safely, and everything went well as far as fording the Arkansas River. Here, they entered the desert waste between the Arkansas and Cimarron Rivers. No one in the party had been over the route before, and they found no trail, no guiding landmark. Mirages deceived them and led them astray, and the caravan wandered for two days without water, their condition becoming desperate. Smith decided to ride ahead and find a way for the others. Following a buffalo trail, he came upon the Cimarron River but found the stream bed dry. Knowing the nature of such rivers, he scooped out a hole in the bottom, which slowly filled with water. Stooping down to drink, never dreaming of danger, he was mortally wounded by arrows shot by skulking Comanche. He staggered to his feet and killed two of his assailants before death ended the fight. After much suffering, his companions reached Santa Fe, New Mexico, but their leader had paid the toll of the wilderness.

The Trapper’s Characteristics

It is difficult in these latter days to comprehend the nature and life of those sturdy wanderers of the mountain and plain, the early trappers. They were soon marked by their environment and developed a peculiar character. The nature of their service affected their appearance, language, habits, and dress. The hard life of the trapper impressed itself on all his features. In author Hiram Chittenden’s words:

“He was ordinarily gaunt and spare, browned with exposure, his hair long and unkempt, which, with his dress, often made it difficult to distinguish him from the Indian. The constant peril of his life and the necessity of unremitting vigilance gave him a kind of piercing look, his head slightly bent forward and his deep eyes peering from under a slouch hat or whatever head-gear he might possess as if studying the face of the stranger to learn whether friend or foe. Overall, he impressed one as taciturn and gloomy, and his life did, to some extent, suppress gayety and tenderness. He became accustomed to scenes of violence and death, and the problem of self-preservation was of such paramount importance that he had but little time to waste upon ineffectual reflections.”

Habits of thrift were practically unknown among these men. They were utterly improvident, apparently so by deliberate choice. They scorned all efforts at the economy and were always poor, spending every cent as soon as it was received.

The earliest trappers to push out beyond the Missouri River were probably French, of the class known as ” free,” unconnected with any big companies, working one or two together independently and selling wherever they could get the best prices for their furs. However, the French trapper preferred the open Plains and only occasionally could be induced to follow his trade into the mountains. With few exceptions, the mountain trapper was of American blood and training. Before the War of 1812, trapping in the Rocky Mountains was a venture in which only hostile Indians and the rough nature of the country were to be considered. After that time, it became largely a struggle for supremacy between the organized fur companies of New York, St. Louis, Missouri, and Mackinaw, Michigan. Manuel Lisa, Andrew Henry, William Ashley, Milton and William Sublette, Robert Campbell, John S. Fitzpatrick, and James Bridger, each in turn, crept up the Missouri River or struggled across the Plains; each had from 100 to 300 men behind him, and each one was eager to outwit the others, jealous and suspicious of every stranger. The silent mountain wilderness hid many a deed of violence and treachery. But, this was invariably the work of the company men. From the beginning to the end of the fur trade, the “trappers” formed a class by themselves. Their story is in every way honorable. Agnes C. Laut epitomized it well in her Story of the Trapper:

The crime of corrupting natives can never be laid to the free trapper. He carried neither poison nor what was worse than poison to the Indian — whiskey — among the native tribes. The free trapper lived on good terms with the Indians because his safety depended on the Indians. Renegades like James Bird, the deserter from the Hudson’s Bay Company, or Rose, who abandoned the Astorians, or James Beckwourth of apocryphal fame, might cast off civilization and become Indian chiefs, but, after all, these men were not guilty of half so hideous crimes as the great fur companies of boasted respectability. Nathaniel Wyeth of Boston, Massachusetts, and Captain Benjamin Bonneville of the army, whose underlings caused such murderous slaughter among the Root Diggers, were not free trappers in the true sense of the term.

Nathaniel Wyeth was an enthusiast who caught the fever of the wilds. Captain Benjamin Bonneville was an adventurer whose men shot down more Indians in one trip than all the free trappers of America shot in a century. As for the desperado Harvey, his crimes were committed under the walls of the American Fur Company’s fort. Before they joined the Astorians, McLellan, Crooks, John Day and Daniel Boone, Kit Carson, and John Colter are names that stand for the true type of free trapper.”

Fights between Whites and Indians

During these years of exploration and trading, while the land yet remained a wilderness wandered over only by little parties of free or employed trappers, the Great Plains and the waters bordering them were the scene of certain events of sufficient historical importance to warrant brief mention. The first recorded fight between Americans and Indians in this region occurred in September 1807 at the Arikara villages on the Missouri River. Here, Ensign Pryor of the Army, with 50 men endeavoring to escort a Mandan chief back to his tribe, was attacked by Arikara onshore and compelled to retreat after fifteen minutes of hot fighting. The loss of the whites was three killed and ten wounded, one mortally. This point on the river was later the scene of various conflicts, the most serious being the attack on Ashley’s men in June 1823. This battle was fought partly on land and partly on water and was practically a defeat for the whites, who lost fourteen killed and about as many wounded. It resulted in an army expedition under Colonel Leavenworth being dispatched up the river. A three-day battle was waged, and neither side could claim victory. A treaty of peace was patched up, but the Arikara continued to be troublesome all through the years of the fur trade.

Earliest Steamboats on the Upper Missouri

Going West with a party by way of the Platte River, William Ashley took a six-pounder wheeled cannon to Utah Lake with him. This is believed to be the first wheeled vehicle to cross the Plains north of the Santa Fe Trail. In 1831, the first steamboat navigated the upper Missouri River. This was the “Yellowstone,” with Captain Young. It proceeded as far as Fort Tecumseh. The following year, this boat reached Fort Union at the mouth of the Yellowstone, and by 1859, steamers had pushed up as far as Fort Benton, near where the Teton River joins the Missouri River.

In 1837, the Indian tribes of the northern Plains were visited by the plague of smallpox. It raged with fearful effect among the Arikara, Mandan, and Assiniboine, spreading westward to the Crow and Blackfeet. The scourge is said to have been introduced by the passage of the annual steamboat of the American Fur Company, the “St. Peters,” which had several cases on board. The Mandan suffered most severely, with only about 30 remaining alive, and they were mostly boys and old men. Chittenden estimates the total loss in the several tribes attacked at more than fifteen thousand, which makes mortality almost impossible in the history of plagues, considering the probable original population. A writer of the time said: “The destroying angel has visited the unfortunate sons of the wilderness with terrors never before known and has converted the extensive hunting grounds, as well as the peaceful settlements of these tribes, into desolate and boundless cemeteries.”

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated March 2024.

About the Author: This article was written by Randall Parrish as a chapter of his book, The Great Plains: The Romance of Western American Exploration, Warfare, and Settlement, 1527-1870; published by A.C. McClurg & Co. in Chicago, 1907. Parrish also wrote several other books, including When Wilderness Was King, My Lady of the North, Historic Illinois, and others. The text as it appears here, however, is not verbatim, as it has been edited for clarity and ease for the modern reader.

Also See:

Trading Posts and Their Stories

List of Old West Explorers, Trappers, Traders & Mountain Men