![]() Adapted from Larry McMurtry’s bittersweet 1966 novel of the same name by McMurtry and director Peter Bogdanovich, The Last Picture Show delineates the quiet, desperate lives of the citizens of Anarene, Texas, from November 1951 to October 1952. The film is a pure Janus-headed product of the New Hollywood. Bogdanovich pours the new wine of sexual frankness available to filmmakers after the inauguration of the MPAA ratings system into old bottles borrowed from the cellars of classic Hollywood cinema, namely those older films’ expressive visual grammar and obliquely suggestive dialogue.

Adapted from Larry McMurtry’s bittersweet 1966 novel of the same name by McMurtry and director Peter Bogdanovich, The Last Picture Show delineates the quiet, desperate lives of the citizens of Anarene, Texas, from November 1951 to October 1952. The film is a pure Janus-headed product of the New Hollywood. Bogdanovich pours the new wine of sexual frankness available to filmmakers after the inauguration of the MPAA ratings system into old bottles borrowed from the cellars of classic Hollywood cinema, namely those older films’ expressive visual grammar and obliquely suggestive dialogue.

As an erstwhile film critic and historian, Bogdanovich drew formal and technical inspiration from his years spent programming films from Hollywood’s Golden Age at MoMA. He also solicited advice from houseguest Orson Welles when it came to shooting the film in black and white, and employing long, unbroken takes rather than break up important scenes. As Welles reportedly put it: “That’s what separates the men from the boys.” And it’s advice that Bogdanovich clearly took to heart for The Last Picture Show.

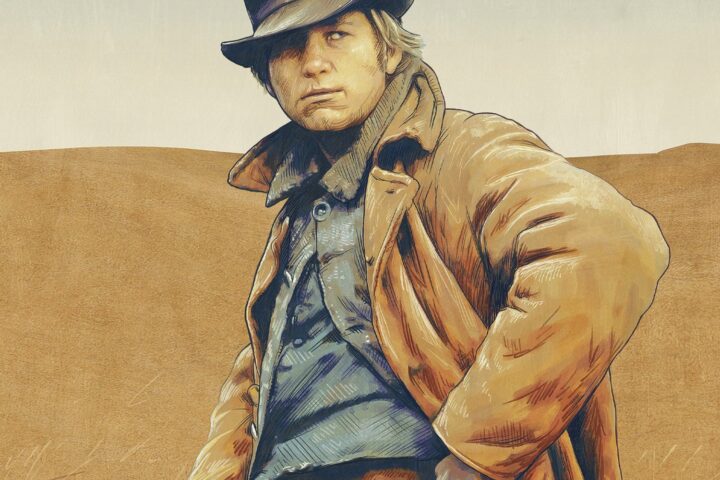

The film opens with the camera panning along the mostly deserted main street of this one-stoplight town, the wind howling and dead leaves swirling in dizzying vortices. the claustrophobia of Anarene’s dead-end existence is rendered even more desolate by Robert Surtees’s cinematography. Early scenes show withdrawn high school football player Sonny Crawford (Timothy Bottoms) being run through the wringer of the locals’ disapproval over the team’s recent trouncing. Failure can lead to disaffection, a disregard for the alleged verities of school spirit and civic pride. In Sonny’s case, that’s illustrated to perfection late in The Last Picture Show when he dejectedly mouths the words to the school anthem.

These opening scenes firmly establish the town’s conservative values, as well as the film’s presiding tone of tragicomic melancholy. And nothing expresses the self-styled Republic of Texas’s aggrandized sense of importance and cultural isolation quite so succinctly as an early smash cut. Used to supremely comic effect, it juxtaposes an urbane English teacher (John Hillerman) lecturing his bored class on Keats’s ode to truth and beauty with chaw-chomping Coach Popper (Bill Thurman) goading the basketball team (“Get a move on, you pissants!”).

The Last Picture Show was one of the first films to employ a song score, composed exclusively of period-specific tunes, often playing diegetically from radios, jukeboxes, and phonographs. Though this sort of thing has been done to death since, especially within the confines of the teen sex comedy that Bogdanovich at least in part helped to inaugurate (think everything from Porky’s to Superbad), it’s never been handled with as much impactful subtlety. Of note are the contrasting versions of “Cold, Cold Heart” heard in Sam the Lion’s café and Jacy’s (Cybill Shepherd) bedroom: Hank Williams’s plaintive warble speaks to a kind of heartfelt sincerity, whereas Tony Bennett puts his city-slicker rendition across like a smooth operator.

The sole escape route available to the citizens of Anarene proves to be sexual passion. Its flicker and roar informs each of the central relationships, from the humiliating sexual initiation that a group of high school boys forces on the intellectually disabled Billy (Sam Bottoms), to the triangle that develops between best friends Sonny and Duane (Jeff Bridges) and the manipulative and perpetually dissatisfied Jacy. The fact that Jacy experiences her own sexual misadventures with initially impotent Duane and then older lothario Abilene (Clu Gulager)—who memorably has his way with her atop a pool table—lends the character more depth than she might otherwise possess. Shepherd’s cannily nuanced performance also helps round Jacy out.

Perhaps the most heartbreaking scene in the film is Sam the Lion’s mournful monologue concerning recollected passion and present dissatisfaction. As Sam crouches at the edge of a fishing tank, surrounded by bare mesquite trees, the camera slowly moves in on, then back out from, a close-up on his face. Just then, the sun escapes the clouds to cast its dazzling blaze as an objective correlative for his paean to an old flame. These sudden flare-ups of uncontrollable desire, what the surrealists use to call l’amour fou, make the weight of the years almost bearable.

The night before Duane ships out, he and Sonny attend the last picture show of the film’s title, a screening of Howard Hawks’s Red River. Bogdanovich and Surtees’s widescreen frame contains the boxy Academy ratio screen showing the iconic scene when John Wayne’s hands the reins over to Montgomery Clift with the laconic “Take ‘em to Missouri, Matt.” While the sense of the baton being passed from one cinematic generation to another couldn’t be any clearer, the scene also sounds the death knell for the classical style of filmmaking.

As Mrs. Mosey (Jessie Lee Fulton), the ticket-taker and popcorn vendor, tells the boys, having “television all the time” seems to have sapped something from the filmgoing experience. But just as one frontier closes, be it Old Hollywood or the Old West, another one opens. For Duane, it may be far-flung adventures in Southeast Asia; for the members of the New Hollywood, it was a briefly opened window on revitalized filmmaking and venturesome storytelling.

When Sonny resumes his affair with Ruth Popper (Cloris Leachman) after an ill-advised fling with Jacy, her anger at his careless love slowly gives way to a faltering renewal of her desire. This haunting, enigmatic scene plays out almost entirely through exchanged looks, understated gestures, and the sort of oblique dialogue that Hawks referred to as “three cushion.” The couple sit hand-in-hand as Ruth reassures Sonny, and the camera moves steadily away, dissolving slowly into a lateral pan back across the empty main street and ending on the now-abandoned Royal Theater, an almost apocalyptic scene of diminution and loss.

Image/Sound

Sourced from a fresh 4K scan of the original 35mm camera negative, the UHD transfer of The Last Picture Show looks terrific. The increased dynamic range improves significantly on the image depth and clarity when compared to the 2010 Blu-ray released as part of Criterion’s America Lost and Found: The BBS Story box set. Black levels are deeper and darker. Grain looks rich and suitably cinematic. The sole audio offering is a sturdy English LPCM mono track that admirably conveys the numerous period-specific needle drops.

Extras

The major addition here, included on a separate Blu-ray disc, is the inclusion of both the theatrical cut and extended director’s cut (in black and white) of Texasville, Peter Bogdanovich’s 1990 seriocomic sequel to The Last Picture Show. Otherwise, the extras duplicate those found on the 2010 Blu-ray. There are two worthwhile commentaries: a rambunctious track featuring Bogdanovich and actors Cybill Shepard, Randy Quaid, Cloris Leachman, and Frank Marshall; and a more sedate and far more technical track with Bogdanovich flying solo. Picture This, George Hickenlooper’s excellent two-part documentary, which was filmed during the making of Texasville, offers some hilarious comments from the residents of Archer City, Texas. Laurent Bouzereau contributes two pieces from 1999: a solid making-of overview and an insightful sidebar interview with Bogdanovich. The booklet includes a loving essay from critic Graham Fuller and extracts from an interview with Bogdanovich about Texasville.

Overall

Peter Bogdanovich’s affecting look at small-town Americana, released during the heart of the New Hollywood era, gets a terrific UHD upgrade from the Criterion Collection.

Since 2001, we've brought you uncompromising, candid takes on the world of film, music, television, video games, theater, and more. Independently owned and operated publications like Slant have been hit hard in recent years, but we’re committed to keeping our content free and accessible—meaning no paywalls or fees.

If you like what we do, please consider subscribing to our Patreon or making a donation.