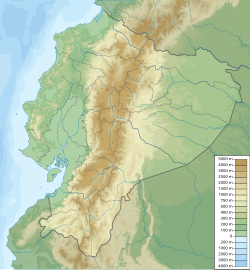

0°19′19″N 78°07′18″W / 0.32194°N 78.12167°W The Inca-Caranqui archaeological site is located in the village of Caranqui on the southern outskirts of the city of Ibarra, Ecuador. The ruin is located in a fertile valley at an elevation of 2,299 metres (7,543 ft). The region around Caranqui, extending into the present day country of Colombia, was the northernmost outpost of the Inca Empire and the last to be added to the empire before the Spanish conquest of 1533. The archaeological region is also called the Pais Caranqui (Caranqui country).

| Location | Ecuador |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 0°19′19″N 78°07′18″W / 0.32194°N 78.12167°W |

| Type | archaeological site |

| History | |

| Founded | early 1500s |

| Site notes | |

| Condition | remnants only |

Background

editPrior to the arrival of the Incas, the region north of Quito for 160 kilometres (99 mi) to near the Colombian border consisted of several small-scale chiefdoms including the Caranqui, Cayambe, Otavalo, and Cochasquí. The names of the first three are preserved in names of 21st century towns and cities and the last is the name given a prominent pre-Incan ruin. Caranqui is the collective name used to describe the chiefdoms, although Caranqui may not have been the most powerful of them. These chiefdoms appear to have been similar in language, artistic techniques, subsistence, and settlement patterns.[1]

The Caranqui and other Andean people of northern Ecuador are identified by Juan de Velasco as the Cara people and Cara culture, supposed rulers of the legendary kingdom of Quito, from which comes the name of the Ecuadorian capital of Quito.[2][3][4]

The chiefdoms were located in the Ecuadorian Sierra between the Guayllabamba River and the Mira River and had an estimated pre-Inca population of 100,000 to 150,000.[5]

A characteristic of the pre-Inca Caranqui region is the presence of many clusters of large man-made earthen mounds, locally called "tolas", dated from 1200 to 1500 CE.[6] Most are found in the inter-montane basin surrounding the Imbabura Volcano, at elevations from 2,200 metres (7,200 ft) to 3,000 metres (9,800 ft). The climate at these altitudes is suitable for growing maize, the chief food crop of the pre-Columbian (and present day) inhabitants. The tolas, which number in the hundreds, with many more having been destroyed, are up to 200 metres (660 ft) on each side and 10 metres (33 ft) to 15 metres (49 ft) in height. Archaeological research indicates they were used as platforms for elite residences, ceremonies, and burials.[7]

Inca conquest

editSpanish chronicler Miguel Cabello de Balboa tells the story of the Inca conquest of northern Ecuador. The Incas, hailing from the austere high Andes of southern Peru, found the generally lower altitudes of Andean Ecuador to be a rich and lush land. The Emperor Topa Inca Yupanqui (ruled c. 1471-1493) began the conquest of Ecuador, encountering heavy resistance from the local chieftains. His son and successor, Huayna Capac (ruled c. 1493-1525) completed the conquest. Operating from the Inca northern capital of Tumebamba, modern day Cuenca, Huayna Capac built a complex of pukaras (hilltop fortresses) at Pambamarca to defeat the Cayambes, encircled Caranqui with several additional pukaras, and then advanced on the recalcitrant chiefdoms. After military campaigns that may have endured more than a decade, the Incas finally achieved victory near the present-day city of Ibarra.[8]

According to Cabello de Balboa, Huayna Capac ordered the massacre of the male population of Caranqui in retribution for its resistance. The massacre took place on the shores of a lake, known until the present day as Yaguarcocha or "Blood Lake." The final Inca victory can be dated between the 1490s to as late as 1520. Spanish chroniclers cite the participation in the battle of Huayna Capac's son, the future emperor Atahualpa. which supports the later date.[9] Supporting the early date is the claim that Atahualpa was born in Caranqui about 1500 CE. A statue of Atahualpa and the Museum of Atahualpa are located in the town.[10][citation needed]

Caranqui was the northernmost area fully incorporated into the Inca Empire, although the Inca fortified Rumichaca Bridge 75 kilometres (47 mi) further north on the present-day border of Ecuador and Colombia.[11] Living on both sides of the border were the Pasto people who were only partially conquered by the Incas.[12]

In the 21st century, Caranqui is most commonly spelled Karanki. The Caranqui lost their language, probably Barbacoan, in the 17th or 18th century, and now speak Kichwa, the Ecuadorian dialect of Quechua, and Spanish in common with other highland peoples.[13]

The Inca-Caranqui site

editAfter the Inca conquest, Caranqui became a major garrison town for the Inca army to maintain control over the surrounding area.[14]

The Spanish chronicler Pedro Cieza de León visited Caranqui in 1544. He described it as the ruin of a major Inca center with a Temple of the Sun, a central plaza with a large water pool, a garrison of Inca troops, and an acllawasi which housed 200 aclla, the sequestered women of the Incas. It is unclear whether the construction was mostly accomplished in the early 16th century by Huayna Capac or in the 1520s by Atahualpa. Atahualpa may have used the site for his royal investiture and wedding (c. 1525) after the death of his father.[15]

Most of the former Inca center has been destroyed by urban development. Still existing are two standing walls with doors and niches near the center of the village of Caranqui. A semi-subterranean pool, excavated in 2008 on a vacant lot purchased by the town, is the outstanding feature of the site. The pool is made of finely-cut stone and was the religious/ceremonial center of the Inca settlement. The rectangular pool is about 10 metres (33 ft) by 16 metres (52 ft) in size with walls about one meter in height. Canals, water spouts, and drains enabled the pool to be filled and drained. Although water pools as temple centerpieces are found in other Inca sites associated with Huayna Capac, such as Quispiguanca in the Sacred Valley of Peru, the pool at Caranqui is unusually large suggesting that it was ritually used by large numbers of people.[16]

Several Inca structures have been found near the pool. An Inca great hall (kallanka) and central plaza are hypothesized to have adjoined the pool complex on the west.[17]

References

edit- ^ Bray, Tamara L. and Echeverría Almeida, José (2014), "The Late Imperial Site of Inca-Caranqui, Northern highland Ecuador at the End of Empire", Nampo Pacha, journal of Andean Archaeology, Vol. 34, No. 2, p. 182

- ^ Onofrio, Jan (1995), Dictionary of the Indian Tribes of the Americas, Vol. 1, 2nd edition, American Indian Publishers, pp. 220-221

- ^ Rostworowski, María. History of the Inca Realm. Translated by Iceland, Harry B. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Porras Barrenechea, Raúl. Los cronistas del Perú.

- ^ Newson, Linda A. (1995), Life and Death in Early Colonial Ecuador, Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, pp. 39-40

- ^ Smith, Julian (2001), "The Water Temple of Inca-Caranqui", Archaeology, Vol 66, No. 1, p. 46. Downloaded from JSTOR.

- ^ Bray and Echeverria, pp. 182-183

- ^ Bray and Echeeverria, pp. 177-181

- ^ Bray and Echeverría, pp. 179-181.

- ^ "TURISMO CARANQUI". February 5, 2011.

- ^ Almeida Reyes, Dr. Eduardo (2015), "El Camino del Inca en las Sierra Norte del Ecuador y su Valoracion Turistica", Revista de Invetigacion Cientifica, No, 7, pp. 75-87

- ^ Newson, pp. 30-31

- ^ Cara language (Caranqui), http://www.native-languages.org/cara.htm, accessed 5 May 2017

- ^ Newson, p. 33

- ^ Bray, Tamara L. and Echeverría, José, "Saving the Palace of Atahualpa: The Later Imperial Site of Inca-Caranqui, Imbabura Province, Northern Highland Ecuador", https://www.doaks.org/research/support-for-research/project-grants/reports/2008-2009/bray-echeverria, accessed 26 Apr 2017

- ^ Bray and Echeverría, pp. 183-193

- ^ Bray and Echeverría, p. 188