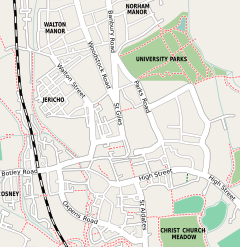

Lady Margaret Hall (LMH)[3] is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in England, located on a bank of the River Cherwell at Norham Gardens in north Oxford and adjacent to the University Parks.[3] The college is more formally known under its current royal charter as "The Principal and Fellows of the College of the Lady Margaret in the University of Oxford".[4]

| Lady Margaret Hall | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| University of Oxford | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

Arms: Or, on a chevron between in chief two talbots passant and in base a bell azure a portcullis of the field. | ||||||||||||

| Location | Norham Gardens, Oxford OX2 6QA | |||||||||||

| Coordinates | 51°45′53″N 1°15′15″W / 51.76483°N 1.254036°W | |||||||||||

| Full name | The College of the Lady Margaret in the University of Oxford | |||||||||||

| Latin name | Aula Dominae Margaretae | |||||||||||

| Motto | Souvent me Souviens (Old French) | |||||||||||

| Motto in English | I often remember | |||||||||||

| Founders | Lavinia and Edward Talbot | |||||||||||

| Established | 1878 | |||||||||||

| Named for | Lady Margaret Beaufort | |||||||||||

| Sister college | Newnham College, Cambridge | |||||||||||

| Principal | Stephen Blyth | |||||||||||

| Undergraduates | 400[1] (2022/2023) | |||||||||||

| Postgraduates | 325[1](2022/2023) | |||||||||||

| Endowment | £42.55 million (2022)[2] | |||||||||||

| Website | www | |||||||||||

| Boat club | www | |||||||||||

| Map | ||||||||||||

The college was founded in 1878, closely collaborating with Somerville College. Both colleges opened their doors in 1879 as the first two women's colleges of Oxford. The college began admitting men in 1979.[3] The college has just under 400 undergraduate students, around 200 postgraduate students and 24 visiting students.[5] In 2016, the college became the only college in Oxford or Cambridge to offer a Foundation Year for students from disadvantaged backgrounds.

In 2018, Lady Margaret Hall ranked 21st out of 30 in Oxford's Norrington Table, a measurement of the performance of students in finals.[6]

The college's colours are blue, yellow and white. The college uses a coat of arms that accompanies the college's motto "Souvent me Souviens", an Old French phrase meaning "I often remember" or "Think of me often", the motto of Lady Margaret Beaufort, who founded Christ's College and St John's College at Cambridge, and after whom the college is named.

The principal, since October 2022, is Stephen Blyth.[7] Notable alumni of Lady Margaret Hall include Benazir Bhutto, Michael Gove, Nigella Lawson, Josie Long, Emma Watson, Ann Widdecombe, Ann Leslie and Malala Yousafzai.

History

editFounding

editIn June 1878, the Association for the Higher Education of Women was formed, aiming for the eventual creation of a college for women in Oxford. Some of the more prominent members of the association were George Granville Bradley, Master of University College, T. H. Green, a prominent liberal philosopher and Fellow of Balliol College, and Edward Stuart Talbot, Warden of Keble College. Talbot insisted on a specifically Anglican institution, which was unacceptable to most of the other members. Some of the Anglican members of the association had specifically wanted to endow an Anglican college after Moncure Conway from the humanist South Place Religious Society in London offered a large sum of money towards a secular women's college; the established church was already concerned that University College London, which had recently become the first university to admit women, would lead "advanced women" away from Christianity.[8]

The two parties eventually split, and Talbot's group founded Lady Margaret Hall, while T. H. Green founded Somerville College.[9] Lady Margaret Hall opened its doors to its first nine students in 1879. The first 21 students from Somerville and Lady Margaret Hall attended lectures in rooms above a baker's shop on Little Clarendon Street.[10] Despite the college's High Anglican origins, not all students were devout Christians.

The college was named after Lady Margaret Beaufort, mother of King Henry VII, patron of scholarship and learning. The first principal was Elizabeth Wordsworth, the great-niece of the poet William Wordsworth and daughter of Christopher Wordsworth, Bishop of Lincoln.

Growth and development

editWith a new building opening in 1894, the college expanded to 25 students.[11][12]

The land on which the college is built was formerly part of the manor of Norham that belonged to St John's College. The college bought the land from St John's in 1894, the other institution driving a hard bargain and requiring a development price not only on the practical building land but also on the undevelopable water meadows. However, this land purchase marked a change in ambition from occupying residential buildings for teaching purposes to erecting buildings befitting an educational institution.

In 1897, members of Lady Margaret Hall founded the Lady Margaret Hall Settlement,[13] as part of the settlement movement. It was a charitable initiative, originally a place for graduates from the college to live in North Lambeth where they would work with and help develop opportunities for the poor.[14][15] Members of the college also helped found the Women's University Settlement, which continues to operate to this day, as the Blackfriars Settlement in south London.[16]

Before 1920, the university refused to give academic degrees to women and would not acknowledge them as full members of the university. (Some of these women, nicknamed the steamboat ladies, were awarded ad eundem degrees by Trinity College Dublin, between 1904 and 1907.[17]) In 1920 the first women graduated from the college at the Sheldonian Theatre and the principal at the time, Henrietta Jex-Blake, was given an honorary degree.[18]

During the Second World War women were not permitted to fight on the front line, and thus many of the students and fellows took up other roles to aid in the war effort, becoming nurses, firefighters and ambulance drivers.[19] The Fellows' Lawn was dug up and the students grew vegetables as part of the Dig for Victory campaign.[18]

In 1979, one hundred years after its foundation, the college began admitting men as well as women; it was the first of the women's colleges to do so, along with St. Anne's.[20]

Members of the college

editIn 1919, J. R. R. Tolkien started to give private tuition to students at Oxford, including members of LMH, where his tuition was much needed given the college's limited resources and tutors in its early years. Later his daughter, Priscilla Reuel Tolkien, attended the college, graduating in 1951.[21]

In 1948, Harper Lee, the future author of To Kill a Mockingbird, was a visiting student at LMH.[22]

In 2017, Malala Yousafzai, the youngest-ever Nobel Prize Peace laureate and Pakistani campaigner for girls' education, became a student of the college;[23] she described the interview as "the hardest interview of [her] life", and received an offer of AAA in her A-Levels.[24] She graduated in 2020.[25] Also in 2017, prospective Chemistry student Brian White faced deportation at the hands of the Home Office,[26] but was able to take up his place at the college.[27]

Foundation year

editLady Margaret Hall is the only Oxford college to offer a foundation year; the scheme recruits students from minority and underrepresented backgrounds, and offers successful applicants lower grade requirements than the standard Oxford entry grades. Students choose a subject to specialise in, and also take courses in study skills and other general subject areas,[28][29] with the aim that they progress to an undergraduate degree at the college after a year of study.[30] Pupils live in the college and have access to the same university facilities, both academic and social, as other students.[29]

Modelled after a programme at Trinity College, Dublin,[31] the four-year pilot scheme began in 2016 with 10 students,[28][32] seven of whom went on to study at Oxford, with the other three receiving offers from different Russell Group universities.[28] It was praised by David Lammy, a Labour MP who said the foundation year is "exactly the sort of thing that needs to be done", and by Les Ebdon, director of Office for Fair Access, who described the programme as "innovative and important".[30]

Buildings and grounds

editThe development of the college's buildings is perhaps best thought of as a zigzag, beginning in the 1870s at the end of Norham Gardens and making its way down towards the River Cherwell, and then running back towards Norham Gardens forming quadrangles on the return journey. The following account of the buildings moves through the college as these spaces emerge for a visitor entering the college at the Porters' Lodge and walking to the river. Because of the way the college developed, the dates and styles of the buildings enclosing the quadrangles are not all of a piece.

Laetare Quadrangle

editThe Laetare quadrangle was completed in March 2017 and includes both the college's newest and oldest buildings. The main entrance consists of the front gates flanked by classical columns along with the Porters' Lodge (2017). Unlike most other Oxford colleges, the Porter's Lodge is freely accessible 24/7 to visitors and members of the public even during term time, and visitors are not charged for entry. It is also wheelchair accessible, and is participating in the Safe Lodge Scheme, in which students from other participating colleges who feel vulnerable or unsafe can go there and receive free transportation back to their own college, which is later charged to their student account.[33] On the North West side the Donald Fothergill Building (2017) contains student accommodation while the Clore Graduate Centre (2017) extends further out to the South East towards the University Parks.[34]

The college's oldest buildings are along the southeast side of the Laetare Quadrangle. The college's original house, a white brick gothic villa, is now known as "Old Old Hall", while the adjoining red-brick extension designed by Basil Champneys is known as New Old Hall (1884).[12] Old Old Hall originally housed the college chapel until the construction of the Deneke Building. Opposite the entrance is the Wolfson West (1964), which was previously the entrance to the college.

Old Old Hall, which had been built as a speculative development on land leased from St John's College, was described as an "ugly little white villa" by the college's founder, Bishop Talbot in his 1923 history of the college.[35] On several occasions in the 20th century, consideration was given to demolishing the earliest buildings of the college, but the temptation was resisted.

The only remaining visible evidence of the road that used to run alongside Old Old Hall and past the steps of Talbot Hall are the two large linden trees, which used to line the pavement before the road was removed to allow expansion of the college. The two smaller trees were planted during construction of the quadrangle. The recent expansion designed by John Simpson Architects was modelled after the Porta Maggiore in Rome, in conjunction with the simple façade of the Wolfson West building.

The MCR, located in the Clore Graduate Centre, is named after the first female Prime Minister of Pakistan, Benazir Bhutto, who studied at the college from 1973 to 1977.[36]

Wolfson Quadrangle

editThe architect of the main early college buildings, including Lodge, Talbot and Wordsworth, was Sir Reginald Blomfield, who had earlier worked on other educational commissions such as Shrewsbury School, and Exeter College, Oxford. He used the French Renaissance style of the 17th century for the buildings and chose red brick with white stone facings, setting a tone the college was to continue to follow in later work. These buildings describe the south and east of the Wolfson Quadrangle and run out into the gardens to the east. Blomfield was also involved in establishing and planning the gardens.

The central block, the Talbot Building (1910) on the North East of the main quad houses Talbot Hall and the Old Library (currently a reception and lecture room),[37] while the accommodation for students and tutors is divided between three wings, the Wordsworth Building (1896), the Toynbee Building (1915) and the Lodge Building (1926).[38]

Talbot Hall contains some fine oak panelling donated by former students to honour Elizabeth Wordsworth and, prior to the Deneke Building, was used as a dining hall for the students. In recent years, it is used to house termly live music nights among other college events.

The portraits in the Hall include the work of notable artists; among the portraits of principals are:

- Sir J. J. Shannon's portrait of Dame Elizabeth

- Philip de László's of Miss Jex-Blake

- Sir Rodrigo Moynihan's of Dr Grier

- Maud Sumner's of Miss Sutherland

In the old Library is a marble statue by Edith Bateson.

On the North West is the Lynda Grier building (1962) housing the college library;[39] this was officially opened by Queen Elizabeth II in 1961.[40] The ground floor of Lynda Grier was originally student accommodation but in 2006 it was converted into a law library, which was opened that year by Cherie Blair.[41] The library was of great importance when founded as women were not permitted to use the Bodleian Library, and thus is relatively large for an Oxford college. Since 2016 the library has also featured a feminist book collection curated by Associate Fellow Emma Watson, called "Our Shared Shelf". This collection supports a feminist book club that runs at the college.[42] The Briggs room originally contained the entire archive of rare and antiquarian books donated to the college over the years. However, due to its size of around 2,000 books, the archive is now stored in the Lawrence Lacerte Rare Books Room in the new Law Library extension on the ground floor. The collection includes a Quran created c. 1600 and a Latin translation of Galileo's Dialogo from 1663.[43]

Lynda Grier and Wolfson West were designed by Raymond Erith. In recent years the Wolfson Quadrangle, in contrast to many Oxbridge quadrangles, has been planted with wildflowers instead of an intensively managed, striped quadrangle lawn.

Lannon Quadrangle

editNamed after former principal, Dame Frances Lannon, the quadrangle consists of the Sutherland Building (1971) and the Pipe Partridge Building (2010).[44] Behind this is Sutherland's sister building, Kathleen Lee (1972), which houses the JCR.

The first phase of the recent plan to expand the college, the Pipe Partridge Building, was completed in early 2010 and was opened by the Chancellor of the University of Oxford, Lord Patten of Barnes, in April 2010.[45]

The Pipe Partridge Building includes the 136-seat Simpkins Lee Theatre,[46] a dining hall, seminar rooms and 64 new undergraduate study bedrooms.[47]

It won the Georgian Group award for the best new building in the classical tradition.[48]

Chapel and Deneke

editTo the northeast extends the large Deneke Building (1932) along with the hall and the college's Byzantine-style chapel where the choir practises and carol services are held in Michaelmas term. These were designed by Giles Gilbert Scott. The dining hall has a reputation for serving the best meals of any Oxford college, and is one of only a few Oxford colleges to serve Halal meals. The chapel has simple decoration with several paintings on the walls, and a statue of Margaret Beaufort that lies in the central section of the chapel. The passageway that leads to the chapel is referred to within the college as "Hell's Passage". The name was derived from the 19th-century illustrations of Dante's Inferno, by John D. Batten, that used to decorate its walls.[49]

The chapel is in the form of a Greek cross and was dedicated by the college's founder Edward Stuart Talbot, in January 1933.[50]

In the autumn of 2019, Andrew Foreshew-Cain became Chaplain. In April 2019, he and other LGBT clergy in the Church of England started the Campaign for Equal Marriage in the Church of England, calling on the church to allow same-sex couples to be married in Church of England parishes and to stop discriminating against people in such marriages.[51]

Gardens and grounds

editLady Margaret Hall is one of the few Oxford colleges that backs onto the River Cherwell. It is set in spacious grounds (about 12 acres (49,000 m2)). The grounds include a set of playing fields, netball and tennis courts, a punt house, topiary, and large herbaceous planting schemes along with vegetable borders. There is a Fellows' Garden – hidden from view by tall hedgerows – and a Fellows' Lawn, on which walking is forbidden.

Student life

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2022) |

The Junior Common Room (JCR) is a physical room as well as being the association of the undergraduate members of the college. It represents its members to the college authorities and facilitates activities and budgets as well as clubs and societies. Officers are elected by the student body to communicate internally and externally on matters regarding student life.[52]

Graduate students have similar support from that provided for the JCR in the Middle Common Room (MCR).

In 2022, Lady Margaret Hall was the first Oxford college to sign a government-backed pledge on ending non-disclosure agreements in cases of sexual misconduct.[53] This followed reporting by The Times that eight female LMH students felt unsafe after the college's response to their complaints of student sexual violence between 2015 and 2021. One undergraduate said that she was threatened with expulsion if she spoke about being raped by a man who was previously reported to the college for sexual violence, and was made to sign a confidentiality agreement by the then Principal Alan Rusbridger.[54] The college initially disputed the undergraduate's claim, but under Rusbridger's successor Christine Gerrard settled the case[55] and paid damages to the woman.[56] Gerrard described the pledge as part of reforms to strengthen safeguarding procedures.[53]

Accommodation

editAccommodation is always provided for undergraduates for three years of their study, and provided for some graduates. The accommodation is found throughout college with a ballot system giving the first choice of room to the students of higher years. The Deneke Building exclusively contains accommodation for first-year undergraduates and students visiting from other universities. However, the first College Disparities Report created by Oxford's Student Union ranked the college as one of the poorest Oxford colleges in terms of asset wealth, with one of the listed consequences of these disparities being that undergraduate students will pay an average of £5,000 more in rent during the course of their studies than those at wealthier colleges.[57]

Boating

editGiven the River Cherwell running past the bottom of LMH's grounds, the students have always had a strong history of spending time by or on the river with the first boat, Lady Maggie, purchased in 1885. The punt house, by tradition, opens on May Day.

Sports

editIn addition to university-wide societies, students at Lady Margaret Hall can also join societies specific to the college.[58] The college has a gym, found near the entrance by Pipe Partridge.

Rowing

editLMH's rowing club, Lady Margaret Hall Boat Club (LMHBC) is one of the largest sports clubs within the college. In recent years, the club has won blades in OURCs events multiple times. The club has a boat house shared with Trinity College on Boat House Island by Christ Church Meadows, along with a purpose-built erg shed, constructed to aid in training.

The Men's 1st VIII have raced in the Temple Challenge Cup at Henley Royal Regatta on several occasions.[59] On multiple years including 2018 and 2019, members of the club have rowed in The Boat Race, an annual competition between Oxford and Cambridge.[60][61]

Like other UK rowing clubs, the college's boat club has distinctive blazers that can be awarded by the club to members who attain membership of certain VIIIs or race with distinction in Summer Eights or Torpids. These blazers have blue and yellow trim and a blue Beaufort portcullis on them, which is the emblem of the boat club and increasingly of other sports clubs.

Rowing blades commemorating success in the intercollegiate rowing competitions decorate the walls of the bar.

Football

editThe college football ground is situated adjacent to Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies and is shared with St Catherine's College and Trinity College.

Art collection

editIn light of its history, the hall has a collection of portraits of early/distinguished women academics. Early Principals Lynda Grier, Dame Lucy Sutherland and Sally Chilver, along with other members of the college, were keen collectors of contemporary art and bequeathed many of these works to the college.

A Fellow in Fine Art, Elizabeth Price, was shortlisted for the Turner Prize in 2012.[62]

The college's art collection includes works by:[citation needed]

Coat of arms

editThe college's coat of arms features devices that recall those associated with its foundation:[citation needed]

- The portcullis is from the arms of Lady Margaret Beaufort

- The bell is a symbol of the Wordsworth family.

- The talbot dogs represent Edward Talbot.

The original coat of arms consisted of three daisies intertwined and bore the motto "Ex solo ad solem", meaning "From the earth to the sun", and can be seen to adorn Talbot Hall, and the Wordsworth and Toynbee buildings. The previous coat of arms gave its name to one of the early college student publications from the 1890s – The Daisy.[63]

After the 50th anniversary of the college, the coat of arms was replaced, now encompassing features that represent the history and founding of the college.

-

Blazon: Or, on a chevron between in chief two talbots passant and in base a bell azure a portcullis of the field.

-

Ex solo ad solem

Deneke talks

editIn the 20th century, the yearly Deneke talks were held in memory of Philip Maurice Deneke who died in 1924. Lectures in this series included "Goethe on nature and science" in 1942 by Nobel laureate Charles Scott Sherrington,[64] and in 1933, Albert Einstein gave the talk "Einiges zur atomistic", concluding the address as follows: "The deeper we search, the more we find there is to know, and as long as humanity exists I believe it will always be so."[65] Margaret Deneke, daughter of Philip Deneke, wrote of the talk in her memoirs:[66]

The Deneke Lecture was packed and many of our friends failed to get seats. Sir Charles Sherrington took the Chair. Whilst Dr. Einstein was speaking and using his blackboard I thought I understood his arguments. When someone at the end begged me to explain points I could reproduce nothing. It had been the Professor's magnetism that held my attention.

— 'What I Remember' Vol.2, pg.26, Ref: MPP 3 A 2/2

Culture and traditions

editLiterature

editIn Phillip Pullman's The Secret Commonwealth, the character Lyra Belacqua attends an Oxford college, St Sophia's, which bears many similarities to Lady Margaret Hall: from its location on the map seen in "Lyra's Oxford" to being one of the first colleges to offer women an education.[67]

A thinly disguised version of the college appeared as "Lady Matilda's College" in an episode of Lewis; portions of the episode were filmed within the hall.[68]

The grounds, along with those of Trinity College, Oxford, were the basis for Fleet College in the American author Charles Finch's novel set in Oxford University, The Last Enchantments.[69]

Death on the Cherwell by Mavis Doriel Hay includes a St Simeon's College, located approximately on the site of Lady Margaret Hall.[70]

Fire and Hemlock by Diana Wynne Jones had a St Margaret's College, which is based on Lady Margaret Hall.[71]

The fictional St Scholastika's College in Val McDermid's 2010 novel Trick of the Dark is a formerly all-female college located in North Oxford, adjacent to the University Parks, with grounds backing onto the river, and buildings of red and yellow brick; it thus appears to be inspired as much by Lady Margaret Hall as by McDermid's own alma mater, St. Hilda's College, Oxford.[72]

Royal visits

editQueen Elizabeth II visited the hall in 1961.[73]

Charles, Prince of Wales visited the college in 2006.[74]

Anne, Princess Royal visited the college in 2014.[75]

Steam locomotive

editA Great Western Railway 6959 Class locomotive named Lady Margaret Hall, number 7911, was built in 1950.[citation needed]

It was one of the "Modified Hall" class and it was in service in the South East until December 1963.[76]

Gardens

editUnusually for Oxford colleges, students are permitted to walk on the Talbot Quadrangle, the main quad of the college.[citation needed] In Trinity term, a spiral of wildflowers are planted, creating a grass walkway into the centre of the quad. This is the only wildflower quad in Oxford.[citation needed] There is a circular wooden bench dedicated to Iris Murdoch in the college gardens where she used to go walking.[77]

Formal Hall

editThe college's candlelit Formal Hall is held every Friday of term.[citation needed]

Lady Margaret Hall is one of nine Oxford colleges to use the "two-word" Latin grace; this grace is also used by five colleges at the University of Cambridge. The person presiding at High Table says the grace in two parts at formal meals. The first half of the grace, the ante cibum, is said before the meal starts and the second, the post cibum, once the meal's conclusion. It is as follows:

Benedictus benedicat – "May the Blessed One give a blessing"

Benedicto benedicatur – "Let praise be given to the Blessed One" or "Let a blessing be given by the Blessed One"

In contrast to some other colleges, gowns are not worn to formal hall, though they are still required at special occasions such as the Scholars' dinner and the Founders' and Benefactors' dinner.

Poet in Residence

editThe college has a poet in residence.[78]

Chapel

editThe chapel at LMH holds weekly evensong every Friday, with services led by Andrew Foreshew-Cain, as well as Catholic communions and other seasonal services such as the Christmas carol service and the Ash Wednesday service. The LMH Chapel Choir is led by Paul Burke.[79]

Notable people

editNotable members

edit-

Nigella Lawson, journalist and food writer

-

Michael Gove, politician

-

Ann Widdecombe, politician

-

Malala Yousafzai, Nobel Peace Prize winner and female education activist

-

Emma Watson, actress and feminist advocate

Alumni of the college (who are termed Senior Members) include:

- Gertrude Bell, writer and diplomat

- Dame Harriett Baldwin, politician and chair of the Treasury Select Committee

- Benazir Bhutto, former prime minister of Pakistan

- Neil Ferguson, epidemiologist

- Michael Gove, politician

- Eglantyne Jebb, founder of Save the Children

- Nigella Lawson, journalist and celebrity television cooking show presenter

- Eliza Manningham-Buller, former director general of MI5

- Barbara Mills, former Director of Public Prosecutions

- Pauline Neville-Jones, former Minister of State for Security and Counter-Terrorism

- Dominic Raab, politician

- Marina Warner, writer

- Baroness Warnock, philosopher

- C. V. Wedgwood, historian

- Ann Widdecombe, politician

- Malala Yousafzai, youngest-ever Nobel Prize laureate and female education activist

Notable fellows and academics

editPrincipals

editNotable principals of the college include:

See also

edit- Gunfield, next to the college

References

edit- ^ a b "Student statistics". University of Oxford. 2023. Retrieved 11 March 2024.

- ^ "Lady Margaret Hall : Annual Report and Financial Statements : Year ended 31 July 2022" (PDF). p. 31. Retrieved 11 March 2024.

- ^ a b c "About Lady Margaret Hall". Oxford Royale Academy. Oxford Programs Limited. Retrieved 18 August 2017.

- ^ "Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford Charter" (PDF). Lady Margaret Hall. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ^ "Student numbers | University of Oxford". Ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- ^ "Undergraduate Degree Classifications | University of Oxford". Ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 10 September 2018.

- ^ "The Principal". Retrieved 9 October 2022.

- ^ Schwartz, Laura. "Religion and the Women's Colleges". Women at Oxford 1878–1920. University of Oxford.

- ^ Alden's Oxford Guide. Oxford: Alden & Co., 1958; pp. 120–21

- ^ Frances Lannon (30 October 2008). "Her Oxford". Times Higher Education.

- ^ "Lady Margaret Hall". British History Online. Institute of Historical Research. Retrieved 18 August 2017.

- ^ a b "LMH, Oxford – New Old Hall". Lmh.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 11 March 2017.

- ^ "Lady Margaret Hall Settlement :: About". Lmhs.org.uk. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- ^ "The Lady Margaret Hall Settlement". The Lady Margaret Hall Settlement (LMHS). LHMS. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- ^ "Records of Lady Margaret Hall Settlement". The National Archives. Gov.uk. Retrieved 17 August 2017.

- ^ "Our History". www.blackfriars-settlement.org.uk. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ^ "A Timeline of the History of Women in Trinity". A Century of Women in Trinity College. Archived from the original on 29 November 2016. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- ^ a b "College Timeline". Lady Margaret Hall. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ^ "Ambulance driver, 1918". Lady Margaret Hall. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ^ "Principal led switch to mixed-sex college". Oxford Mail. 27 November 2014. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

- ^ Drout, Michael D. C. (6 November 2006). J. R. R. Tolkien Encyclopedia: Scholarship and Critical Assessment. Routledge. ISBN 1135880344.

- ^ Cep, Casey (2019). Furious Hours: Murder, Fraud, and the Last Trial of Harper Lee. Knopf. ISBN 9781101947869., p. 163.

- ^ News Team (17 August 2017). "Malala Yousafzai accepted to read PPE at LMH". The Oxford Student. Archived from the original on 26 August 2017. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- ^ McIntyre, Niamh (12 March 2017). "Malala Yousafzai hopes to study at Oxford University if she achieves AAA offer". The Independent. Retrieved 24 October 2017.

- ^ "Malala Yousafzai completes Oxford University exams". BBC News. 19 June 2020. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- ^ Khomami, Nadia (30 August 2017). "Student with Oxford place 'does not know what to do if deported'". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ^ Scott, John (4 September 2017). "Brian White: Oxford-bound Wolverhampton student WINS battle to stay in the UK". Expressandstar.com. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

- ^ a b c Foley, Holly (4 October 2017). "Trinity's Access Programme is Teaching Oxford Lessons". The University Times. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- ^ a b "Studying on the Foundation Year". Lady Margaret Hall. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- ^ a b Adaams, Richard (20 April 2016). "Oxford college launches pilot scheme to recruit disadvantaged students". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 8 August 2017.

- ^ "Oxford University tries a new approach to recruiting poor students". The Economist. 10 December 2016. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- ^ Thomson, Alice; Sylvester, Rachel (19 October 2017). "Varaidzo Kativhu: 'I just assumed Oxford university would be for the posh'". The Times. Retrieved 4 December 2017.

- ^ "Safe Lodge". www.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 12 September 2024.

- ^ "New buildings 2007–2017". Lady Margaret Hall. Retrieved 2 April 2017.

- ^ Stamers-Smith, Eileen (3 August 1996). "Sir Reginald Blomfield's Designs for the Garden of Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford". Garden History. 24 (1): 114–121. doi:10.2307/1587104. JSTOR 1587104.

- ^ "BBC – Oxford University's famous south Asian graduates". news.bbc.co.uk. 5 May 2010. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- ^ "LMH, Oxford – Talbot". Lmh.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 11 March 2017.

- ^ "LMH, Oxford – Eleanor Lodge". Lmh.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 11 March 2017.

- ^ "LMH, Oxford – Library". Lmh.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 11 March 2017.

- ^ "LMH Library". Lady Margaret Hall. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- ^ "LMH Library". Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford. Retrieved 17 January 2010.

- ^ "Associate Fellow". Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford. Retrieved 12 September 2024.

- ^ Fishwick, James. "Oxford LibGuides: Lady Margaret Hall Library: Special Collections". libguides.bodleian.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ^ "LMH, Oxford – Pipe Partridge". Lmh.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 11 March 2017.

- ^ "opening of the Pipe Partridge Building". Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford. 26 April 2010. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- ^ "Simpkins Lee Theatre". Simpkinsleetheatre.com. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- ^ "Lady Margaret Hall Phase I and II". Johnsimpsonarchitects.com. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- ^ "Pipe Partridge wins an award". Lmh.aox.ac.uk. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- ^ "Hell's Passage?". lmh.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- ^ Alden (1958)

- ^ Siddons, Edward (7 May 2019). "The rebel priest: 'Gay people in the church are not going to go away'". The Guardian. Retrieved 11 January 2021.

- ^ "LMH JCR Student Union Page". Oxford SU. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

- ^ a b "Lady Margaret Hall signs pledge to end gagging clauses". BBC News. 27 April 2022. Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- ^ O'Neill, Sean (31 March 2022). "Oxford college rape claim: 'They tried to convince me not to complain'". The Times. Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- ^ O'Neill, Sean (1 April 2022). "Minister demands action at Oxford college that silenced rape accuser". The Times. Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- ^ Adams, Richard (1 April 2022). "Oxford college pays damages to woman after alleged rape by fellow student". The Guardian. Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- ^ "Report". www.oxfordsu.org. Retrieved 12 September 2024.

- ^ "Societies and clubs | Lady Margaret Hall". Lady Margaret Hall. Retrieved 2 August 2017.

- ^ "Events". Lmhboatclub.wordpress.com. 16 October 2014. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

- ^ Quarrell, Rachel (4 March 2013). "University Boat Race: men and women weigh in at same event ahead of Oxford and Cambridge race". Telegraph.co.uk. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

- ^ "LMH rowers featuring in tomorrow's Boat Race | Lady Margaret Hall". www.lmh.ox.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 1 April 2018.

- ^ "Lady Margaret Hall, University of Oxford | Art UK". artuk.org. Retrieved 8 August 2017.

- ^ "The Daisy". Lady Margaret Hall. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ^ Sherrington, Charles Scott (25 March 1949). Goethe on nature and science: the Philip Maurice Deneke lecture delivered at Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford on the 4th March 1942. University Press. OCLC 664820863.

- ^ Clark, Ronald (28 September 2011). Einstein: The Life and Times. A&C Black. ISBN 978-1-4482-0270-6.

- ^ "An Einstein Lecture". Lady Margaret Hall. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ^ "Lyra's Oxford: His Dark Materials". The Book Trail. Retrieved 27 October 2024.

- ^ Elman, Leslie Gilbert (7 September 2011). "Inspector Lewis: Old, Unhappy, Far Off Things". Criminal Element. Retrieved 27 October 2024.

- ^ "The Last Enchantments". Tumblr. Retrieved 23 June 2014.

- ^ "Death on the Cherwell (British Library Crime Classics) Page 15 Read online free by Mavis Doriel Hay". bookreadfree.com. Retrieved 27 October 2024.

- ^ "OXFORDSHIRE TOURIST GUIDE". www.wessex.me.uk. Retrieved 27 October 2024.

- ^ Penn, J. F. (5 October 2014). "Inspiration For Writing Crime Thriller The Skeleton Road With Val McDermid | J.F.Penn". J.F.Penn | Thrillers, Dark Fantasy, Crime, Horror. Retrieved 27 October 2024.

- ^ "LMH Library". Lady Margaret Hall. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- ^ "BBC NEWS | UK | Charles tribute for Prayer Book". news.bbc.co.uk. 16 September 2006. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- ^ "Stock Photo – 18 February 2014: HRH The Princess Royal, Princess Anne at Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford University, to present The Ockenden International Prizes. HRH Princess Anne presents Lynn". Alamy. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- ^ "Great Western Railway Hall class details". Greatwestern.org.uk. Retrieved 8 August 2017.

- ^ Sheridan, Benn (27 November 2016). "Iris Murdoch's Oxford Life". Cherwell. OSPL. Retrieved 22 August 2017.

- ^ "Kieron Winn is new Poet in Residence at LMH". Lady Margaret Hall. Retrieved 25 March 2020.

- ^ "Chapel Services and Weekly Events". Lady Margaret hall.