The Queen's College is a constituent college of the University of Oxford, England.[2] The college was founded in 1341 by Robert de Eglesfield in honour of Philippa of Hainault, queen of England.[3] It is distinguished by its predominantly neoclassical architecture, primarily dating from the 18th century.

| The Queen's College | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| University of Oxford | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

Arms: Argent, three eagles displayed gules, beaked and legged or, on the breast of the first, a mullet of six points of the last. | |||||||||||||

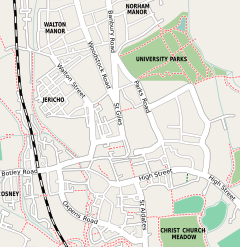

| Location | High Street, Oxford | ||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 51°45′12″N 01°15′04″W / 51.75333°N 1.25111°W | ||||||||||||

| Full name | The Queen's College in the University of Oxford | ||||||||||||

| Latin name | Collegium Reginae | ||||||||||||

| Motto | Reginae erunt nutrices tuae | ||||||||||||

| Established | 1341 | ||||||||||||

| Named for | Philippa of Hainault | ||||||||||||

| Sister college | Pembroke College, Cambridge | ||||||||||||

| Provost | Claire Craig | ||||||||||||

| Undergraduates | 343[1] (2019–20) | ||||||||||||

| Postgraduates | 173 | ||||||||||||

| Website | www | ||||||||||||

| Boat club | www | ||||||||||||

| Map | |||||||||||||

In 2018, the college had an endowment of £291 million,[4] making it the fourth-wealthiest Oxford college (after Christ Church, St. John's, and All Souls).

History

editThe college was founded in 1341 as "Hall of the Queen's scholars of Oxford" by Robert de Eglesfield (d'Eglesfield), chaplain to the then queen consort Philippa of Hainault, after whom the hall was named.[3] Robert's aim was to provide clergymen for his native Cumberland and where he lived in Westmorland (both part of modern Cumbria). In addition, the college was to provide charity for the poor. The college's coat of arms is that of the founder; it differs slightly from his family's coat of arms, which did not include the gold star on the breast of the first eagle. The current coat of arms was adopted by d'Eglesfield because he was unable to use his family's arms, being the younger son. D'Eglesfield had grand plans for the college, with a provost, 12 fellows studying theology, up to 13 chaplains, and 72 poor boys. However, the college did not have the funding to support such numbers, and initially had just two fellows.[citation needed]

The college gained land and patronage in the mid-15th century, giving it a good endowment and allowing it to expand to 10 fellows by the end of the century. By 1500, the college had started to take paying undergraduates, typically sons of the gentry and middle class, who paid the fellows for teaching. There were 14 of these in 1535; by 1612, this had risen to 194. The college added lectureships in Greek and philosophy. Provost Henry Robinson obtained an Act of Parliament incorporating the college as "The Queen's College" in 1585, so Robinson is known as the second founder.[citation needed]

Following the new foundation, the college had a good reputation and flourished until the 1750s. Joseph Williamson, who had been admitted as a poor boy and went on to become a fellow, rose to Secretary of State and amassed a fortune. He funded a new range on Queen's Lane built in 1671–72. Following a bequest of books from Thomas Barlow, a new library was built between 1693 and 1696 by master builder John Townesend. A further bequest from Williamson of £6,000, along with purchase of the buildings along the High Street, allowed a new front quad to be built and for the remaining medieval buildings to be replaced. This was completed by 1759 by John's son William Townesend.[5][6] The college gained a large number of benefactions during this time, which helped to pay for the buildings and bring in more scholars from other, mostly northern, towns.[citation needed]

From the 1750s, as with other Oxford colleges, standards dropped. The Oxford commission of 1850–1859 revised the statutes and removed the northern preference for fellows and most of the students. Over the coming years, requirements for fellows to be unmarried were relaxed, the number of fellows required to have taken orders and studied theology was reduced, and in 1871 the Universities Tests Act allowed non-conformists and Catholics.[7]

Like many of Oxford's colleges, Queen's admitted its first mixed-sex cohort in 1979, after more than six centuries as an institution for men only.[8]

Naming

editThe college is named for its first patroness, Queen Philippa. Established in January 1341 'under the name of the Hall of the Queen's scholars of Oxford' (sub nomine aule scholarium Regine de Oxon), the college was subsequently called the 'Queen's Hall', 'Queenhall' and 'Queen's College'. The Queen's College, Oxford Act 1584 (27 Eliz. 1. c. 2) sought to end this confusion by providing that it should be called by the one name "the Queen's College";[9] in practice, the definite article is usually omitted. The full name of the College, as indicated in its annual reports, is The Provost and Scholars of The Queen's College in the University of Oxford.[10] Queens' College in Cambridge positions its apostrophe differently and has no article, as it was named for multiple queens (Margaret of Anjou and Elizabeth Woodville).[citation needed]

In popular culture

editIn April 2012, as part of the celebrations of the Diamond Jubilee of Elizabeth II, a series of commemorative stamps was released featuring A-Z pictures of famous British landmarks. The Queen's College's front quad was used on the Q stamp, alongside other landmarks such as the Angel of the North on A and the Old Bailey on O. [11]

Traditions

editOne of the most famous feasts of the College is the Boar's Head Gaudy, which originally was the Christmas dinner for members of the College who were unable to return home to the north of England over the Christmas break between terms, but is now a feast for old members of the College on the Saturday before Christmas.[12]

Buildings

editFront Quad

editThe main entrance on the High Street leads to the front quad, which was built between 1709 and 1759. There are symmetrical ranges on the east and west sides, while at the back of the quad is a building containing the chapel and the hall.[6] The architect Nicholas Hawksmoor, a leading figure of the English Baroque style, provided a number of designs that were not used directly but that heavily influenced the final design. In the cupola above the college entrance is a statue of the British queen Caroline of Ansbach by the sculptor Henry Cheere; the legend 'Carolina Regina, 12 November 1733' may be found marking the laying of the foundation stone of the screen wall, which is visible from the High Street.[6]

Back Quad

editA second and older quad lies to the north of the hall and chapel. The west side consists of the library. The east side is the Williamson building, which was originally built to a design by the architect Christopher Wren, known for his work in the English Baroque style, but has been largely rebuilt since then.[6]

Chapel

editThe chapel is noted for its Frobenius organ in the west gallery.[13][14] It was installed in 1965, replacing a Rushworth and Dreaper organ from 1931. The earliest mention of an organ is 1826. The Chapel Choir has been described as "Oxford's finest mixed-voice choir" and continues to perform termly concerts, recent examples of which include Handel's Messiah and Bach's St John Passion.[15][16] The chapel has stood virtually unchanged since it was consecrated by the Archbishop of York in 1719.[citation needed]

Holy Communion is celebrated every Sunday morning and at other times, and is open to all communicant members of any Christian church or denomination. The Sunday evening service takes the traditional form of Choral Evensong, which is also held on Wednesday and Friday evenings during term. Morning and evening prayer is said daily, and at other times some like to use the stillness for their own prayer. Baptisms, confirmations, and weddings are also conducted for members or former members of the College.[citation needed]

Library

editThe Upper Library

editThe Upper Library has been a focal point for the College ever since its construction at the end of the 17th century. The ceiling plasterwork, its most outstanding feature, was designed by James Hands, whilst the library itself was built by John Townsend. The designer remains unknown, although a likely candidate is Henry Aldrich, who was Bishop of Oxford and Dean of Christ Church, as well as chief communicator between Christopher Wren and the College whilst the Back Quad was being designed.[17][18] Unlike many other similar rooms in Oxford libraries, the Upper Library remains as a silent reading room for students open during staffed hours.[19]

Eighteenth Century Globes and Orrery

editOn display in the middle of the library are two eighteenth century papier maché Senex globes and an orrery from the same period. John Senex was the foremost globe maker of the eighteenth century,[20] and also crafted the miniature globe featured in the orrery. The globes are now found in cases that were designed and fitted by Welsh furniture designer Bernard Allen in 2007, after being removed from the library for a period of time in 2002 for structural repair and restoration by renowned English globe conservator Sylvia Sumira.[citation needed]

The Benjamin Cole orrery was a gift to the College in 1763 from a Group of Gentleman Commoners of the College, recorded in two entries in the Benefactors' Book, as well as on an inscription in the lunar calendar scale.[21] The instrument is made of brass, steel, and wood, contained within a wooden case and resting on a mahogany stand with a glazed cover.[22] Johnathan Betts, in an Excerpt from A report following the servicing and inspection of The Queen's College Grand Orrery in 2016, describes the instrument as standing

on a fine mahogany table with six finely carved cabriole legs, the whole covered with a multi-panelled protective glass shade which can be locked securely onto the table, preventing access to the orrery.[22]

In the same article, Betts illustrates the orrery,

fitted in a mahogany twelve-sided case, with lacquered brass mounts and surmounted, on a brass pillared gallery, with a large lacquered brass hemispherical armillary structure. The mechanical orrery itself incorporates within its compass the solar system out to Mars, including the Earth and Moon, with additional mountings fixed on the outside of the case for attaching static models of Jupiter and Saturn.[22]

The turning of the orrery is a traditional event at Queen's, done by hand only once every few years or on special occasions. Only two people are permitted to turn the orrery: the Patroness of the College, a position most recently occupied by The Queen Mother, and the Sedleian Professor of Natural Philosophy, a Fellow of Queen's.[23] This event most recently took place on 4 February 2020, during the Hilary term, with professor Jonathan Keating as the honorary orrery-turner.[citation needed]

The Lower and New Libraries

editThe open cloister below the Upper Library was enclosed in the 19th century to form the Lower Library, which now houses the bulk of the lending collection. The lending collection consists of around 50,000[24] with an additional 70,000 items in the special collections available by appointment.[25] In April 2017 the New Library opened[26] beneath the Provost's Garden,[27] with an official opening by Old Member Rowan Atkinson taking place in November of the same year.[28]

Annexes

editQueen's is able to provide accommodation for all of its undergraduates, who are divided between the college's main buildings and annexes nearby. Adjacent to college is Carrodus Quad, located just across Queen's Lane. It has been completely refurbished, and now has approximately 80 en-suite rooms for first-year students, as well as a few second- and third-/final-year students with access requirements. The building also houses a conference room, one of the college's music practice rooms (the other one being located in the Back Quad of the main college), and the college gym. The college also owns the Cardo Building opposite the Oxford University Sports centre on Iffley Road (where Roger Bannister ran the first ever four-minute mile in 1954). This building is home to a mixture of second and third years, and features a common room, breakfast room and the college's two squash courts. Near the Cardo Building is the James Street Building, the smallest of the annexes with twelve rooms.[citation needed]

The Florey Building in St Clement's, designed by James Stirling and named after former Queen's Provost and Nobel Prize winner Howard Florey, is a former annex that housed most of the college's first years until 2018, when it fell into disuse following complications that arose in attempts to refurbish the building.[29][30][31] It contains nearly 80 rooms; those on the top floor have a mezzanine level where the students' beds were located. At one end of the building on the ground floor, there is a common room and a breakfast room. Following the closure of the Florey Building in 2018,[32] the former post-graduate annex, St Aldate's House, became the largest undergraduate annex at Queen's, with three floors, 90 en suite rooms, and kitchens shared with up to nine other students. The annex is situated down St Aldate's directly opposite the Christ Church Meadows, near Folly Bridge.[citation needed]

While many postgraduate students choose to live outside College accommodation, two postgraduates annexes are provided: Oxley-Wright House, which is owned by the College, and a portion of the Venneit Close complex, which is rented from North Oxford Property Services (NOPS). The former is a large Victorian house on Banbury Road, near Summertown, with 13 rooms and a large garden.[33] None of the rooms are en suite, and there are 3 bathrooms in the building, each shared between approximately 4 people.[33] The latter includes 18 apartments, each with three study bedrooms, two bathrooms, a kitchen (with a washing machine) and a dining/sitting room.[34] Both annexes are within a 10- to 20-minute walk from the city centre.[citation needed]

Gallery

edit-

The Queen's College, view from the High Street

-

View of the Upper Library, featuring the last remaining part of the medieval college

-

The Queen's College, Back Quad

-

Back Quad, detail

Student life

editQueen's is an active community performing strongly in intercollegiate sport competitions, having a variety of societies and, as one of the larger colleges, hosting triennial Commemoration balls. The 2007 ball coincided with the 666th anniversary of the college.[35]

Queen's is host to a number of dining, drinking and sports societies, as well as some which are more academically orientated such as a medical society.[citation needed]

The JCR, MCR, and Old Taberdar's Room

editThe Junior Common Room (JCR) consists of the collective body of undergraduates at the college, and also refers to the room under the same name, located in the Back Quad, which is the only common room in the college that cannot be booked. The JCR is not to be confused with the JCR General Committee, which consists of all members of the Executive Committee, Equalities Committee, and Welfare Committee, all presidents of college societies and the president of the ball committee, as well as the Academic & Careers Representative, Access and Outreach Representative, Food Representatives, Environment & Ethics Representatives, Student Union Representatives, Stash Representative, Charities Representative, Webmasters, Arts Representative, Antisocial Secretary (a position passed on in a 'hereditary' manner through one's 'College family'), Warden of the Beer Cellar, and the Keeper of the Boars, Bees, and Eagles.

The Middle Common Room (MCR) refers to the postgraduates of the college. Like the JCR, the MCR have an Executive team, which includes the President, Victualler, Vice-President Secretary, Treasurer, Social Secretary, SCR Liaison Officer, LGBTQ+ Officer, Welfare Officer, Environment and Charities Representative, IT Officer, Sports Secretary, Oxford SU Representative, First Year Representative, and Entz Representative (the last four positions being empty as of 2020).[36] The MCR and JCR will often liaise with one another in order to organise events in the college.[citation needed]

The Old Taberdar's Room is a room unique to Queen's, described by the college as

a traditional wood-panelled room, furnished with comfortable sofas and chairs. The room is ideal as a lounge space or for informal discussion based session.[37]

It is open for use by all members of the college, though it is possible to book it for events such as welcome drinks, pre-dinner drinks, student production rehearsals, and society meetings. A Taberdar is specifically "a holder of a scholarship at Queen's College, Oxford".[38]

Sport

editCollege sport at Queen's is organised and funded through the Amalgamated Sports Clubs Committee, consisting of individual club captains and other representatives of college sport.[39] The college competes in most of the intercollegiate Cuppers (tournament style) and league sports, with many 1st teams competing in top divisions.[citation needed]

The college playing field, less than a mile from the main buildings, runs down to the banks of the Isis. It has a football and a hockey pitch, together with hard tennis courts, a netball court and a pavilion. The football ground is nicknamed Fortress Riverside by the club and its supporters, owing to its close proximity to the Isis [citation needed]. The Queen's College shares a rugby pitch nearby with University College. In the summer, the goalposts go down and a cricket square appears in the middle.[citation needed]

On the opposite bank of the river is a boathouse, which Queen's shares with Oriel and Lincoln colleges. The Queen's College Boat Club, founded in 1827, is one of the oldest boat clubs in the world. In 1837, QCBC represented Oxford in a Boat Race against Lady Margaret Boat Club, representing Cambridge, and won. This event, held on the River Thames at Henley-on-Thames, is credited with contributing to support from the town for the establishment of the Henley Royal Regatta, one of the most famous rowing events in the world, in 1839.[40] The college's colours were changed thereafter from red and white to navy blue and white, the colours of the university. Rowing is still a major sport in the College, with the men's first boat winning blades in Torpids 2021[41] and the women's first boat winning blades in both Torpids 2023[42] and Summer Eights 2023.[43] The College was last Head of the river in Torpids and Eights in 1958.

The college's two squash courts are located at the Cardo Building annex on Iffley Road.

Music

editThe Queen's College is host to a mixed-voice Chapel Choir. The singers include Choral Scholars (up to eighteen at any one time) and volunteers, all of whom are auditioned. The Choir sings Evensong three times a week during term, and performs one major concert each term, often with a noted orchestral ensemble. The choir also undertakes regular tours and short visits both within this country and abroad. The Eglesfield Musical Society, named after the founder, is the oldest musical society in Oxford. It organises a substantial series of concerts each year, ranging from chamber music to orchestral works.

College Grace

editAs is the case with many Oxbridge colleges, Queen's uses a Latin grace which is recited every evening before the second sitting of dinner:

Benedic nobis, Domine Deus, et his donis, quae ex liberalitate Tua sumpturi sumus; per Jesum Christum Dominum nostrum. Amen.

A rough English translation: "Bless us, Lord God, and these gifts which we are about to receive through your bounty; through Jesus Christ, our Lord, Amen"

At gaudy dinners this grace is sung by the choir.[citation needed]

Notable alumni

edit- Tony Abbott, 28th Prime Minister of Australia

- Barbara Frances Ackah-Yensu, Justice of the Supreme Court of Ghana

- Joseph Addison, co-founder of The Spectator

- Rowan Atkinson, actor and comedian, known for Blackadder and Mr. Bean

- Michael Barber FRS, chemist and mass spectrometrist

- Jeremy Bentham, English philosopher, and legal and social reformer

- Tim Berners-Lee, inventor of the World Wide Web and director of the World Wide Web Consortium

- Wilfred Bion, British psychoanalyst[44]

- Christopher Bland, British businessman and politician

- Cory Booker, United States Senator from New Jersey

- Vere Gordon Childe, Archaeologist, socialist, excavator of Skara Brae and Maes Howe

- Clayton Christensen, American business academic known for coining "disruptive innovation"

- Myles Cooper, 2nd President of Columbia University

- Frank Cowper, English yachtsman and author

- John Crewdson, Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist for The New York Times

- Ernest Dowson, English poet and prose writer

- Alfred Enoch, English actor

- Howard Florey, Lord Florey, Nobel Laureate and co-developer of penicillin, later Provost of the College

- Oliver Franks, Baron Franks, civil servant and philosopher, Provost of The Queen's College, later Provost of Worcester College

- Eric Garcetti, Mayor of Los Angeles

- Herbert Branston Gray, educationalist

- Leonard Hoffmann, Baron Hoffmann, English jurist and judge

- Edmund Halley, English astronomer

- Fred Halliday, Irish academic, Fellow of the British Academy, Montague Burton Professor of International Relations at London School of Economics

- John Heath-Stubbs, English poet and editor

- King Henry V of England

- Edwin Powell Hubble, American astronomer[45]

- Ruth Kelly, former UK Cabinet and Government Minister

- Kenneth Leighton, twentieth-century English composer

- John Henry Mee, nineteenth-century English composer

- Thomas Middleton, English Jacobean playwright and poet

- John Milbank, Anglican Theologian

- David Moule-Evans, twentieth-century English composer

- David Oliver, Geriatrician. Professor of Medicine for Older People at City University. Former National Clinical Director for Older People Department of Health. President British Geriatrics Society. Visiting Fellow The King's Fund

- John Owen, seventeenth-century English theologian

- Brian Paddick, twice Liberal Democrat candidate for Mayor of London

- Walter Horatio Pater, English essayist

- Richard Rampton, barrister in high-profile cases such as Irving v Penguin Books and Lipstadt, which was the subject of the film Denial

- Benedict Read, Art Historian

- Ryan Max Riley, United States Ski Team skier

- Gilbert Ryle, British philosopher

- Oliver Sacks, neurologist and writer

- Leopold Stokowski, conductor

- Claire Taylor, English cricketer

- William Thomson, Archbishop of York

- Phil Venables, British computer scientist and security specialist

- Charles Leslie Wrenn, English scholar and a Rawlinson and Bosworth Professor of Anglo-Saxon at Pembroke College, Oxford

- John Wycliffe, English theologian

- Adam Zamoyski, historian and author

- Peter Daniell MP, Member of Parliament

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Student statistics". University of Oxford. Archived from the original on 4 July 2019. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- ^ "The Queen's College | University of Oxford". ox.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 1 November 2022. Retrieved 1 November 2022.

- ^ a b "History". The Queen's College, Oxford. Archived from the original on 10 January 2021. Retrieved 1 November 2022.

- ^ "The Queen's College Oxford : Annual Report and Financial Statements : Year ended 31 July 2018" (PDF). ox.ac.uk. p. 20. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 February 2019. Retrieved 5 March 2019.

- ^ "The Queen's College, Oxford". queens.ox.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 10 January 2021. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- ^ a b c d "Oxford's greatest neo-classical college is restored". Country Life. 17 August 2014. Archived from the original on 31 December 2016. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- ^ "The Queen's College | British History Online". british-history.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 5 July 2017. Retrieved 1 May 2017.

- ^ "Launch of the Queen's Women's Network". queens.ox.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 28 February 2019. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- ^ A History of the County of Oxford: Volume 3: "The University of Oxford", 1954, p.132

- ^ Annual Report and Financial Statements, 2011 Archived 23 April 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "First class: A-Z postal portrait of Britain in stamps is complete". Mirror Online. 10 April 2012. Archived from the original on 20 May 2022. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- ^ "The Queen's College". oxocn.org.uk. Archived from the original on 17 December 2021. Retrieved 24 February 2022.

- ^ "The Organ". Choir of The Queen's College, Oxford. Archived from the original on 21 August 2019. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- ^ "The National Pipe Organ Register - NPOR". npor.org.uk. Archived from the original on 12 May 2021. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- ^ "The Chapel Choir of The Queen's College Oxford". Guild Records page. Archived from the original on 16 April 2007. Retrieved 27 April 2007.

- ^ "Archive". Choir of The Queen's College, Oxford. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- ^ "History of the Library". The Queen's College, Oxford. Retrieved 23 September 2024.

- ^ Schapiro, Meyer (1994). Theory and philosophy of art: style, artist, and society. Selected papers. New York: George Braziller. ISBN 978-0-8076-1357-3.

- ^ "Opening Hours - The Queen's College". ox.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 17 January 2016.

- ^ "Dorothy Sloan–Rare Books: Auction 22". dsloan.com. Archived from the original on 2 October 2020. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- ^ Bridgwater, David (28 December 2018). "Bath, Art and Architecture: John Vanderstein at Queen's College, Oxford - Part 12, The Upper Library Doorcase - with some notes concerning the Orrery by Benjamin Cole". Bath, Art and Architecture. Archived from the original on 2 October 2020. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- ^ a b c Betts, Jonathan (December 2016). "Excerpt from A report following the servicing and inspection of The Queen's College Grand Orrery, 2016" (PDF). The Queen's College Library 'Insight' (6, Michaelmas 2016): 15. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 July 2020. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- ^ Shaw, Tessa (September 2011). "The orrery in the Upper Library" (PDF). The Queen's College Library 'Insight' (1, Michaelmas 2011): 15. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 July 2020. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- ^ "The Queen's College, Oxford". queens.ox.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 13 April 2017. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- ^ "The Queen's College, Oxford". queens.ox.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 13 April 2017. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- ^ "The Queen's College, Oxford". queens.ox.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 13 July 2017. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- ^ "The Queen's College, Oxford". queens.ox.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 13 January 2017. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- ^ "The right thing at the right time". The Queen's College, Oxford. Archived from the original on 14 October 2020. Retrieved 19 September 2020.

- ^ "Agenda item - Florey Building, 23-24 St Clement's Street:15/03643/FUL". mycouncil.oxford.gov.uk. 27 April 2016. Archived from the original on 28 October 2021. Retrieved 19 September 2020.

- ^ "Residents hit out at "grotesque" Florey Building extension in East Oxford after plans approved". Oxford Mail. 29 April 2016. Archived from the original on 15 October 2021. Retrieved 19 September 2020.

- ^ Marrs, Colin (19 February 2016). "Avanti's new plans for Florey come under fire". The Architects' Journal. Archived from the original on 21 September 2023. Retrieved 19 September 2020.

- ^ "St Aldate's House | The Queen's MCR | University of Oxford". mcr.queens.ox.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 18 October 2021. Retrieved 19 September 2020.

- ^ a b "Oxley-Wright | The Queen's MCR | University of Oxford". mcr.queens.ox.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 28 December 2020. Retrieved 19 September 2020.

- ^ "Venneit Close | The Queen's MCR | University of Oxford". mcr.queens.ox.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 28 December 2020. Retrieved 19 September 2020.

- ^ "Queen's College Ball". Archived from the original on 22 February 2007. Retrieved 27 April 2007.

- ^ "Members | The Queen's MCR | University of Oxford". mcr.queens.ox.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 27 December 2020. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- ^ "Old Taberdars' Room". The Queen's College, Oxford. Archived from the original on 1 October 2020. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- ^ "Taberdar definition and meaning | Collins English Dictionary". collinsdictionary.com. Archived from the original on 27 April 2021. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- ^ The Queen's College, Oxford University. "The Queen's College". ox.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 22 October 2013. Retrieved 18 October 2013.

- ^ Howard, Henry Charles (1911). The Encyclopaedia of Sport and Games. William Heinemann. p. 53.

- ^ "success on the river!". The Queen's College Newsletter. Retrieved 15 January 2024.

- ^ "Torpids success!". The Queen's College, Oxford. Retrieved 15 January 2024.

- ^ "Women's 1st VIII makes history at Summer Eights". The Queen's College, Oxford. Retrieved 15 January 2024.

- ^ "Wilfred Bion - melanie klein trust". melanie-klein-trust.org.uk. Archived from the original on 9 July 2012. Retrieved 23 December 2012.

- ^ "Rhodes Scholars - the Rhodes Trust". Archived from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 15 April 2011. "For example, the Rhodes Scholar identifiers for Edwin Hubble (American astronomer for whom the Hubble Telescope is named) would be "Illinois & Queen's 1910"."