University College, formally The Master and Fellows of the College of the Great Hall of the University commonly called University College in the University of Oxford[6] and colloquially referred to as "Univ",[7] is a constituent college of the University of Oxford in England.[8] It has a claim to being the oldest college of the university, having been founded in 1249 by William of Durham.[9]

| University College | |

|---|---|

| University of Oxford | |

| |

Arms: Azure, a cross patonce between four [sometimes five] martlets. | |

| Scarf colours: navy, with two narrow yellow stripes a quarter of a scarf-width in from either edge | |

| Location | High Street, Oxford OX1 4BH |

| Coordinates | 51°45′09″N 1°15′07″W / 51.7525°N 1.2520°W |

| Full name | The College of the Great Hall of the University of Oxford |

| Latin name | Collegium Magnae Aulae Universitatis Oxon.[1] |

| Established | 1249 |

| Sister college | Trinity Hall, Cambridge[2] |

| Master | Valerie Amos, Baroness Amos |

| Undergraduates | 425[3] (2023–24) |

| Postgraduates | 219[4] (2023–24) |

| Endowment | £146.084 million (2023) |

| Visitor | Charles III, The Crown ex officio[5] |

| Website | www |

| JCR | Univ JCR |

| MCR | Univ WCR |

| Boat club | University College Boat Club |

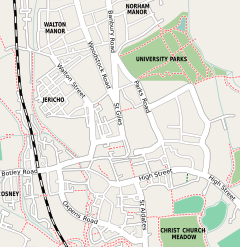

| Map | |

As of 2023, the college had an estimated financial endowment of £146.084 million, and their total net assets amounted to £238.316 million.[10]

The college is associated with a number of influential people, including Clement Attlee, Harold Wilson, Bill and Chelsea Clinton, Neil Gorsuch, Stephen Hawking, C. S. Lewis, V. S. Naipaul, Robert Reich, William Beveridge, Bob Hawke, Robert Cecil, Tom Hooper, and Percy Bysshe Shelley.

History

editA legend arose in the 14th century that the college was founded by King Alfred in 872.[11] This explains why the college arms are those attributed to King Alfred, why the Visitor is always the reigning monarch, and why the college celebrated its millennium in 1872. Most agree that in reality the college was founded in 1249 by William of Durham. He bequeathed money to support ten or twelve masters of arts studying divinity, and a property which became known as Aula Universitatis (University Hall) was bought in 1253.[12] This later date still allows the claim that Univ is the oldest of the Oxford colleges, although this is contested by Balliol College and Merton College.[13][14] Univ was open only to fellows studying theology until the 16th century.[citation needed]

The college acquired four properties on its current site south of the High Street in 1332 and 1336 and built a quadrangle in the 15th century.[15] As it grew in size and wealth, its medieval buildings were replaced with the current Main Quadrangle in the 17th century. Although the foundation stone was placed on 17 April 1634, the disruption of the English Civil War meant it was not completed until sometime in 1676.[1] Radcliffe Quad followed more rapidly by 1719, and the library was built in 1861.[16]

Like many of Oxford's colleges, University College accepted its first mixed-sex cohort in 1979, having previously been an institution for men only.[17]

Buildings

editThe main entrance to the college is on the High Street and its grounds are bounded by Merton Street and Magpie Lane. The college is divided by Logic Lane, which is owned by the college and runs through the centre. The western side of the college is occupied by the library, the hall, the chapel and the two quadrangles which house both student accommodation and college offices. The eastern side of the college is mainly devoted to student accommodation in rooms above the High Street shops, on Merton Street or in the separate Goodhart Building. This building is named after former master of the college, Arthur Lehman Goodhart.[18]

A specially constructed building in the college, the Shelley Memorial, houses a statue by Edward Onslow Ford of the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley – a former member of the college, who was sent down for writing The Necessity of Atheism (1811), along with his friend T. J. Hogg. Shelley is depicted lying dead on the Italian seashore.[19]

The college annexe on Staverton Road in North Oxford houses undergraduate students during their second year and some graduate students.[20]

The college also owns the University College Boathouse (completed in 2007 and designed by Belsize architects)[21] and a sports ground, which is located nearby on Abingdon Road.[22]

Student life

editUniv Alternative Prospectus

editThe Alternative Prospectus is written and produced by current students for prospective applicants. The publication was awarded a HELOA Innovation and Best Practice Award in 2011.[23] The Univ Alternative Prospectus offers student written advice and guidance to potential Oxford applicants. The award recognises the engagement of the college community, unique newspaper format, forward-thinking use of social media and the collaborative working between staff and students.[citation needed]

Grace

editUniversity has the longest grace of any Oxford (and perhaps Cambridge) college.[24] It is read before every Formal Hall, which is held on Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Sundays. The reading is performed by a Scholar of the college and whoever is sitting at the head of High Table (typically the Master, or the most senior Fellow at the table if the Master is not dining).

Original version

editSCHOLAR – Benedictus sit Deus in donis suis.

RESPONSE – Et sanctus in omnibus operibus suis.

SCHOLAR – Adiutorium nostrum in Nomine Domini.

RESPONSE – Qui fecit coelum et terram.

SCHOLAR – Sit Nomen Domini benedictum.

RESPONSE – Ab hoc tempore usque in saecula.

SCHOLAR – Domine Deus, Resurrectio et Vita credentium, Qui semper es laudandus tam in viventibus quam in defunctis, gratias Tibi agimus pro omnibus Fundatoribus caeterisque Benefactoribus nostris, quorum beneficiis hic ad pietatem et ad studia literarum alimur: Te rogantes ut nos, hisce Tuis donis ad Tuam gloriam recte utentes, una cum iis ad vitam immortalem perducamur. Per Jesum Christum Dominum nostrum.

RESPONSE - Amen.

SCHOLAR — Deus det vivis gratiam, defunctis requiem: Ecclesiae, Regi, Regnoque nostro, pacem et concordiam: et nobis peccatoribus vitam aeternam.

RESPONSE - Amen.

English translation

editSCHOLAR — Let God be blessed in his gifts.

RESPONSE — And holy in all his works.

SCHOLAR — Our help is in the Name of the Lord.

RESPONSE — Who has made heaven and earth.

SCHOLAR — May the Name of the Lord be blessed.

RESPONSE — From this time for evermore.

SCHOLAR — Lord God, the resurrection and the life of them that believe, who are always to be praised both among the living and among the dead, we give You thanks for all our founders and other benefactors, by whose gifts we are nourished here for piety and the study of letters; asking You that we, using these Your gifts rightly to Your glory, may be led together with them into eternal life. Through Jesus Christ our Lord.

RESPONSE — Amen.

SCHOLAR — May God grant to the living grace, and to the dead rest; to the Church, the King, and our realm, peace and concord; and to us sinners everlasting life.

RESPONSE — Amen.

People associated with the college

editGovernment and politics

edit-

William Beveridge, economist

-

Felix Yusupov, Russian aristocrat

-

The Viscount Cecil of Chelwood, politician and recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize

-

Bill Clinton, former President of the United States of America (did not graduate)

-

Robert Reich, economic advisor, former U.S. Secretary of Labor, and author

-

William Weld, former Governor of Massachusetts and U.S. presidential candidate

-

Bob Hawke, former Prime Minister of Australia

-

Chelsea Clinton, lead at the Clinton Foundation and Clinton Global Initiative, daughter of Bill and Hillary Clinton

Many influential politicians are associated with the college, including the social reformer and author of the Beveridge Report William Beveridge (who was a master of University College) and two UK Prime Ministers: Clement Attlee and Harold Wilson (a Univ fellow). US President Bill Clinton (though he did not graduate) and Prime Minister of Australia, Bob Hawke were also students. Other heads of state and government to have attended Univ include Edgar Whitehead (Rhodesia), Kofi Abrefa Busia (Ghana), and Festus Mogae (Botswana). Nobel Peace Prize Laureate Robert Cecil studied law at the college, similarly U.S. Supreme Court Associate Justice Neil Gorsuch received a DPhil in law as a Marshall Scholar,[25] while former NATO Supreme Allied Commander Bernard W. Rogers read Philosophy, Politics and Economics as a Rhodes Scholar, and former Court of Justice of the European Communities Judge Sir David Edward read Classics.[26]

Literature and arts

edit-

Percy Bysshe Shelley, Romantic poet

-

George Abbot, former archbishop of Canterbury

-

C. S. Lewis, author of the Chronicles of Narnia

-

Cecil William Mercer, novelist

-

Max Hastings, historian and journalist

-

Nick Robinson, journalist

In the arts, people associated with the college include poet Percy Bysshe Shelley (expelled for writing The Necessity of Atheism), for whom there is a memorial in college; Poet Laureate Andrew Motion; author of the Narnia books C. S. Lewis; and a Nobel Prize for Literature winner, Sir V. S. Naipaul. One of the translators of the King James Bible, George Abbot, was a master of the college. The actors Michael York and Warren Mitchell attended Univ, as well as broadcaster Paul Gambaccini.

Science and innovation

edit-

Stephen Hawking, theoretical physicist and cosmologist

-

William Jones, philologist

-

John Radcliffe, physician and academic

-

Rudolph A. Marcus, Nobel Prize-winning chemist

It was due to the college's lack of a mathematics fellow (this is no longer the case) that Stephen Hawking read a natural sciences degree and ended up specialising in physics.[27] Other former students include John Radcliffe (physician), William Jones (philologist), and Edmund Cartwright (inventor). Rudolph A. Marcus, a Canadian-born chemist who received the 1992 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, received a Professorial Fellowship at Univ from 1975 to 1976. A perhaps more unusual alumnus is Prince Felix Yusupov, the assassin of Rasputin.[28]

Univ had the highest proportion of old members offering financial support to the college of any Oxbridge college with 28% in 2007.[29][citation needed]

Other connections

editAlthough not members of University College, the scientists Robert Boyle (sometimes described as the "first modern chemist") and his assistant (Robert Hooke, architect, biologist, discoverer of cells) lived in Deep Hall (then owned by Christ Church and now the site of the Shelley Memorial). The former made a contribution to the completion of University College's current Hall in the mid-17th century.[1]

Samuel Johnson (author of A Dictionary of the English Language and a member of Pembroke College) was a frequent visitor to the Senior Common Room at University College during the 18th century.[1]

Publications

editThe college produces a number of regular publications, especially for alumni.[30]

University College Record

editThe University College Record is the annual magazine sent to alumni of the college each autumn. The magazine provides college news on clubs and societies such as the University College Players and the Devas Club, as well as academic performance and prizes. News about and obituaries of former students are included at the end of each issue.[citation needed]

Editors have included Peter Bayley and Leslie Mitchell.

The Martlet

editThe Martlet is a magazine for members and friends of the college, available in print and online.[30]

Gallery

edit-

University College, on the south side of the High Street.

-

University College, Oxford: aerial view with key and scale.

-

Main Quadrangle of the college.

-

The Shelley Memorial at University College, Oxford.

-

The interior of the chapel of University College, Oxford.

-

University College, Oxford: the library. Line engraving by J.H. Le Keux, 1861, after himself.

-

Courtyard of University College Oxford.

-

The new Boathouse for the University College Oxford Boat Club.

-

Dr Bowen's Room, University College, Oxford.

-

A view of Logic Lane toward the High Street from within University College, Oxford.

See also

edit- University College Oxford Boat Club

- University College Players (college dramatic society)

References

edit- ^ a b c d Darwall-Smith, Robin (2008). A History of University College, Oxford. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-928429-0.

- ^ Daunton, Martin, "From the Master" (PDF), Newsletter: Academic Year 2009/10, Trinity Hall, Cambridge, p. 7, archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2011, retrieved 1 August 2011

- ^ "Student statistics". University of Oxford.

- ^ "Student statistics". University of Oxford.

- ^ "Statutes of University College, Oxford" (PDF).

- ^ "THE MASTER AND FELLOWS OF THE COLLEGE OF THE GREAT HALL OF THE UNIVERSITY COMMONLY CALLED UNIVERSITY COLLEGE IN THE UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD". Charity Commission For England and Wales. Retrieved 16 April 2024.

- ^ "University College Oxford". University College Oxford.

- ^ "University College | University of Oxford". www.ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 1 November 2022.

- ^ "History - University College Oxford (Univ)". University College Oxford. Retrieved 1 November 2022.

- ^ "University College Oxford: Annual Report and Financial Statements: Year ended 31 July 2023" (PDF). ox.ac.uk. p. 35. Retrieved 20 February 2024.

- ^ "Official College Web-site". Archived from the original on 17 May 2013. Retrieved 23 August 2013.

- ^ "Oxford History". Retrieved 23 August 2013.

- ^ "Q&A: oldest established". balliolarchivist.wordpress.com. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- ^ Brockliss, L. W. B. (2016). The University of Oxford: A History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 64–66. ISBN 9780199243563.

- ^ "University College". british-history,ac.uk. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- ^ "History - University College Oxford (Univ)". University College Oxford. Retrieved 25 September 2023.

- ^ "History - University College Oxford". University College Oxford. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ^ Megarry, R. E. (1997). "Arthur Lehman Goodhart" (PDF). The British Academy. p. 13.

- ^ "Shelley Memorial". University College Oxford. Retrieved 19 March 2021.

- ^ "University College - Oxford University Alternative Prospectus". apply.oxfordsu.org. Retrieved 19 March 2021.

- ^ "University College Oxford Boathouse", e-architect.

- ^ "Univ Buildings Elsewhere". University College Oxford. Retrieved 19 March 2021.

- ^ Oxford admissions teams win innovation awards - University of Oxford Archived 26 April 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Ox.ac.uk. Retrieved 2013-08-12.

- ^ "Food - University College Oxford (Univ) - Food at Univ". University College Oxford. Retrieved 17 September 2022.

- ^ "Judge Neil M. Gorsuch". Administrative Office of the United States Courts. The United States Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 31 January 2017.

- ^ Famous Univites.

- ^ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F. "Stephen William Hawking". MacTutor History of Mathematics archive. University of St Andrews. Retrieved 1 October 2009.

- ^ The History of Univ Archived 5 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine, University College, Oxford.

- ^ Lord Adonis, Education Minister, 2008

- ^ a b "Publications". UK: University College, Oxford. Retrieved 9 August 2018.