Hamburg Temple

| Hamburg Temple | |

|---|---|

The former synagogue, in 2009 | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Reform Judaism (former) |

| Rite | Nusach Ashkenaz |

| Ecclesiastical or organisational status | |

| Status |

|

| Location | |

| Location | Hamburg: – 1844:

|

| Country | Germany |

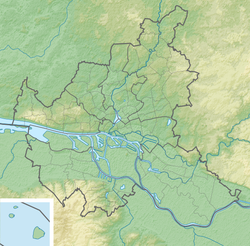

Location of the synagogue in Hamburg | |

| Geographic coordinates | 53°34′38″N 9°59′28″E / 53.57733°N 9.99119°E |

| Architecture | |

| Architect(s) | 1844:

|

| Type | Synagogue architecture |

| Style | 1844: 1931: |

| Date established | 11 December 1817 (as a congregation) |

| Groundbreaking |

|

| Completed |

|

| Construction cost | ℛℳ 560,000 (1931) |

| Specifications | |

| Direction of façade |

|

| Capacity | 1,200 (1931) |

| Materials |

|

| [1][2] | |

The Hamburg Temple (Template:Lang-de) is a former Reform Jewish congregation and synagogue, located in Hamburg, Germany. The congregation was the first permanent Reform Jewish community and the first to have a Reform prayer rite. It operated from 1818 to 1938. On 18 October 1818 the Temple was inaugurated and later twice moved to new edifices, in 1844 and 1931, respectively. The congregation abandoned the synagogue in 1938.

The building has been used as a concert venue since 1949, most recently as the Rolf-Liebermann-Studio, since 2000.

History of the Temple and its congregation

The New Israelite Temple Society (Template:Lang-de in Hamburg) was founded on 11 December 1817 and 65 heads of families joined the new congregation.[3] One of the pioneers of the synagogue reform was Israel Jacobson (1768–1828). In 1810 he had founded a prayerhouse, adjacent to the modern school he ran, in Seesen. On 18 October 1818, the anniversary of the Battle of Nations near Leipzig, the members of the New Israelite Temple Society inaugurated their first synagogue in a rented building in the courtyard between Erste Brunnenstraße and Alter Steinweg in Hamburg's Neustadt quarter (New Town).

Dr. Eduard Kley together with Dr. Gotthold Salomon were the first spiritual leaders of the Hamburg Temple in 1818. The first members included the notary Meyer Israel Bresselau, Lazarus Gumpel and Ruben Daniel Warburg. Later members included Salomon Heine and Dr. Gabriel Riesser, who was chairman of the New Israelite Temple Society from 1840 to 1843.

The new prayer book employed in the Temple was the first comprehensive Reform liturgy ever composed: it omitted or changed several of the formulas anticipating a return to Zion and restoration of the sacrificial cult in the Jerusalem Temple. These changes – expressing the earliest tenet of the nascent Reform movement, universalised Messianism – evoked a thunderous denunciation from Rabbis across Europe, who condemned the builders of the new synagogue as heretics.[4] The religious service of the Hamburg Temple was disseminated at the 1820 Leipzig Trade Fair, where Jewish businessmen from German states, many other European countries, and the United States met. As a consequence, several Reform communities, including New York and Baltimore, adopted the Hamburg Temple's prayer book, which was read from left to right, as in the Christian world.

The members, mostly Ashkenazim, strived to form an independent Jewish congregation besides Hamburg's two other established Jewish statutory corporations, the Sephardic Heilige Gemeinde der Sephardim Beith Israel (בית ישראל; Holy Congregation of the Sephardim Beit Israel; est. 1652; see also Portuguese Jewish community in Hamburg) and the Ashkenazi Deutsch-Israelitische Gemeinde zu Hamburg (DIG, German-Israelite Congregation; est. 1662), however, in 1819 the Senate of Hamburg, then the government of a sovereign independent city-state, declared it would not recognise a potential Reform congregation. Therefore, the New Israelite Temple Society remained a civic association and its members stayed enrolled with the DIG, since one could only quit the DIG by joining another religious corporation. Irreligionism was still a legal impossibility in Hamburg at that time.

With the temple in the Erste Brunnenstraße growing too small in the late 1820s its members applied to build a bigger synagogue. The senate denied the application for a bigger temple in a prominent location, as intended, since this would incite a controversy within the DIG with the other Ashkenazi faithful also demanding a more visible synagogue.[5]: 151 In 1835 the Society started another attempt applying for a building licence, but in 1836 Hamburg's building authority recommended to withhold the application until the senate would have decided the request of Hamburg's Jewry for their emancipation, issued in 1834.[5]: 151 In 1835 the senate had decided against the Jewish emancipation for the time being, but had founded a commission to further investigate the question.[5]: 151

In 1840 then the New Israelite Temple Society (meanwhile comprising 300 families) insisted to get a building licence.[5]: 151 This time then Hamburg's Ashkenazi Chief Rabbi Isaac Bernays intervened at the senate in order to make it deny the application.[5]: 151 However, the senate granted the licence on 20 April 1841 and the cornerstone was laid on 18 October 1842.[5]: 151 Several sites had been bought, thus to allow building the new Temple with a wide forecourt in the courtyard, however, not - unlike the original intention - visible from public streets.[5]: 151 Johann Hinrich Klees-Wülbern was commissioned to design the plans for the new temple. The old temple was profaned. The lawyer and notary Gabriel Riesser enforced that the land was registered on the name of the New Israelite Temple Society, till then the senate would register property of Jewish civic association only under names of a natural person.

Temple and congregation since the opening of its second venue

The New Temple Society invited the Hamburg-born Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy to set Psalm 100 (Hebrew: מזמור לתודה, Mizmor leToda) to music for a choir for playing it at the inauguration of the new Temple on 5 September 1844.[6] However, disputes on which translation should be used, Luther's, as preferred by the Calvinist Mendelssohn-Bartholdy, or that of his Jewish grandfather Moses Mendelssohn, as preferred by the Society, prevented the realisation of that project, as can be read from the correspondence between the composer and Maimon Fränkel, the praeses of the Society.[7] Psalm 100 was then most likely sung the traditional Ashkenazi way on entering the Sefer Torah to the new synagogue.[a] Presumably Mendelssohn-Bartholdy then provided his versions of the Psalms 24 and 25 for the inauguration.[9]

On 1 February 1865 a new law abolished the compulsion for Jews to enrol with one of Hamburg's two statutory Jewish congregations.[b] So the members of the New Israelite Temple Society were free to found their own Jewish congregation.[10]: 78 The fact that its members were no longer compelled to associate with the Ashkenazi DIG meant that it could possibly fall apart.[10]: 78 In order to prevent this and to reconstitute the DIG as a religious body with voluntary membership in a liberal civic state the DIG held general elections among its full-aged male members, to form a college of 15 representatives (Repräsentanten-Kollegium), who would further negotiate the future constitution of the DIG.[10]: 78 The liberal faction gained nine, the Orthodox faction 6 seats.<[10]: 78 After lengthy negotiations the representatives enacted the statutes of the DIG on 3 November 1867.[10]: 78 The new constitution provided for tolerance among the DIG members as to matters of the cult (worship) and religious tradition.[10]: 78 This unique model, thus called Hamburg System (Hamburger System), established a two-tiered organisation of the DIG with the college of representatives and the umbrella administration in charge of matters of general Ashkenazi interest, such as cemetery, zedakah for the poor, hospital and representation of the Ashkenazim towards the outside.[10]: 78 The second tier formed the so-called Kultusverbände (worship associations), associations independent in religious and financial matters by their own elected boards and membership dues, but within the DIG, took care of religious affairs.[10]: 78

Each member of the DIG, but also any non-associated Jew, was entitled to also join a worship association, but did not have to.[10]: 78 So since 1868 the Reform movement formed within the DIG a Kultusverband, the Reform Jewish Israelitischer Tempelverband (Israelite Temple association).[10]: 78 The other worship associations were the Orthodox Deutsch-Israelitischer Synagogenverband (German-Israelite Synagogue association, est. 1868) and the 1892-founded but only 1923-recognised conservative Verein der Neuen Dammtor-Synagoge (Association of the new Dammtor synagogue).[5]: 157 The worship associations had agreed that all services commonly provided such as burials, britot mila, zedakah for the poor, almshouses, hospital care and food offered in these institutions had to fulfill Orthodox requirements.[10]: 78

-

Temple, 1st venue (1818–1844), Erste Brunnenstraße, exterior

-

Temple, 2nd venue (1844-1931), Poolstraße, exterior

-

Temple, 2nd venue, interior

-

Temple, 2nd venue, ruin as of 1944, apsis ornament

-

Temple, 3rd venue inside, today's Rolf Liebermann Studio of the NDR

In 1879, Rabbi Max Sänger asked Moritz Henle to come to the Hamburg Temple and Henle decided to accept the offer. He immediately began his work in Hamburg by forming a mixed choir. One member of the mixed choir was Caroline Franziska Herschel, a relative of Moses Mendelssohn. They married in 1882 and from that date on, his wife accompanied Henle during his performances as well as during official functions. In 1883, Dávid Leimdörfer became rabbi at the Temple, where he was also principal of the school for religion as all other rabbis. He died in 1922.

The influence of the Temple movement was not restricted to the liberal community; one of the lasting effects has been the introduction of the sermon in German, also within the Orthodox community. Today Reform Judaism, with its origins in the Hamburg Temple, has circa 2 million members just in the United States.

Third venue: Tempel in the Oberstraße

With the moving of many members of the Israelite Temple Association into new quarters outside the old city centre, especially into the Grindel neighbourhood, they wished their temple closer to their new domiciles.[5]: 161 First demands for a relocation appeared in 1908, in 1924 the moving was decided but delayed due to financial constraints, in 1927 decided a plot on Oberstraße 120 was bought in 1928, after an architectural competition in 1929 the architects Felix Ascher and Robert Friedmann were commissioned.[5]: 161 The new synagogue, Tempel Oberstraße, was built from 1930 to 1931 in Modernist style for about ℛℳ 560,000.[3] On 30 August 1931 the new Temple in the Oberstraße was inaugurated[5]: 162 and it was a great time with the rabbi Bruno Italiener. The temple in the Poolstraße was profaned in 1931 and sold six years later. In 1937 the Israelite Temple Association celebrated a series of festivities for the 120th jubilee of the Hamburg Temple, many of its members celebrated their Passover Seder together in the synagogue and lectures and a great party were held in the temple and its adjacent premises.

The former Temple in the Oberstraße since 1938

After the November Pogrom in 1938 the Nazis closed the Temple, which had not been burnt but realised vandalism of its interior.[5]: 162 Italiener emigrated to the United Kingdom.[3] On 28 November 1940 the legal successor of the DIG, the Jewish Religious Association (Jüdischer Religionsverband in Hamburg), was forced to sell the building for the ridiculous sum of ℛℳ 120,000 to the Colonial Office (Kolonialamt; a legally dependent subunit of Hamburg), which, however, did not realise its plans for the rebuild for its purposes.[5]: 163

While the profaned temple in the Poolstraße was destroyed in the bombing of Hamburg in 1944, the temple and its adjacent community centre in the Oberstraße remained intact and were rented to the bombed-out editorial department of the newspaper Hamburger Fremdenblatt in August 1943.[5]: 163 The ruin of the former Poolstraße temple is preserved until today. In 1946 the city-state rented out the former temple building in the Oberstraße to the British-founded Northwest German Broadcasting (NWDR; Nordwestdeutscher Rundfunk), which acquired the building in 1948.[5]: 163 Meanwhile, the 1945-founded Jewish Community of Hamburg, holding legal succession of the Jewish Religious Association in Hamburg, applied for the rescission of the enforced sale of the Temple in 1940.[5]: 163 So with the pending restitution of the temple the NWDR asked the Jewish Community for its permission before it installed a ceiling in order to separate the synagogue hall into two halls, a broadcasting hall above and a radio drama studio below.[5]: 163 In 1952 the court restituted the temple to the Jewish Trust Corporation, who then sold it to the NWDR in 1953, whose legal successor North German Broadcasting (NDR) owns it until today.[3][5]: 163 Since 1982 the former temple is a listed building.[3] On 6 March 2000 the NDR renamed its studio within the former temple, called at times Studio 10 or Großer Sendesaal (big broadcasting hall) as Rolf Liebermann Studio in honour of the homonymous composer, who led the NDR music department between 1957 and 1959.[3] It is used as a venue for concerts, lectures and other artistic performances.[3]

Clergy

- Rabbis were Eduard Kley (1789–1867), Gotthold Salomon (1784–1862), Naphtali Frankfurter (1810–1866), Hermann Jonas, Max Sänger, David Leimdörfer, Caesar Seligmann (1860–1950), Paul Rieger, Jacob Sonderling, Schlomo Rülf, and Bruno Italiener.

- Chazzanim were David Meldola, Joseph Piza, John Lipman, Ignaz Mandl, Moritz Henle, Leon Kornitzer, and Joseph Cysner, who was deported to Zbaszyn, Poland in the Polenaktion on October 28, 1938.

See also

Notes

- ^ Minute of the meeting of the directorate (Tempel-Direction) of the New Temple Society of 18 May 1844.[8]

- ^ On 4 November 1864 the Hamburg Parliament passed the Law concerning the relations of the local Israelite congregations (Gesetz, betreffend die Verhältnisse der hiesigen israelitischen Gemeinden) with effect of 1 February 1865.

References

- ^ "Poolstraße (Second) Temple in Hamburg". Historic synagogues of Europe. Foundation for Jewish Heritage and the Center for Jewish Art at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. n.d. Retrieved July 7, 2024.

- ^ "Oberstraße (Third) Temple in Hamburg". Historic synagogues of Europe. Foundation for Jewish Heritage and the Center for Jewish Art at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. n.d. Retrieved July 7, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g Büchelmaier, Gaby. "Zehn Jahre Rolf-Liebermann-Studio". NDR.de Das Beste am Norden (in German). Retrieved January 20, 2013.

- ^ Meyer, Michael (1995). Response to Modernity: A History of the Reform Movement in Judaism. Wayne State. pp. 47–61.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Rohde, Saskia (1991). "Synagogen im Hamburger Raum 1680–1943". Die Geschichte der Juden in Hamburg (in German). Vol. 2. Hamburg: Dölling und Galitz. pp. 143–175. ISBN 3-926174-25-0. Die Juden in Hamburg 1590 bis 1990

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link). - ^ Werner, Eric (1985). "Felix Mendelssohn's Commissioned Composition for the Hamburg Temple. The 100th Psalm (1844)". Musica Judaica. Vol. 7. p. 57.

- ^ Hirsch, Lily E. (2005). "Felix Mendelssohn's Psalm 100 Reconsidered". Rivista del Dipartimento di Scienze musicologiche e paleografico-filologiche dell'Università degli Studi di Pavia. Retrieved January 21, 2013.

- ^ Brämer, Andreas (2000). Judentum und religiöse Reform: Der Hamburger Tempel 1817-1938 (in German). Vol. 8. Hamburg: Dölling und Galitz. p. 191. ISBN 978-3-933374-78-3. (Studien zur Jüdischen Geschichte)

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ Todd, Ralph Larry (2003). Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy: Sein Leben – Seine Musik [Mendelssohn: A Life in Music] (in German). Translated by Beste, Helga. Stuttgart: Carus. pp. 513, seq. ISBN 978-3-89948-098-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Lorenz, Ina (1991). "Die jüdische Gemeinde Hamburg 1860 – 1943: Kaisereich – Weimarer Republik – NS-Staat". Die Geschichte der Juden in Hamburg (in German). Vol. 2. Hamburg: Dölling und Galitz. pp. 77–100. ISBN 3-926174-25-0. Die Juden in Hamburg 1590 bis 1990

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link).

Sources

- Gotthold Salomon, Predigten in dem Neuen Israelitischen Tempel, Erste Sammlung, Hamburg: J. Ahrons, 1820

- Digitalisat des Exemplars der Harvard University Library

- Eduard Kley, Gotthold Salomon, Sammlung der neuesten Predigten: gehalten in dem Neuen Israelitischen Tempel zu Hamburg, Hamburg: J. Ahrons, 1826.

- Digitalisat des Exemplars der Harvard University Library

- Gotthold Salomon, Festpredigten für alle Feyertage des Herrn: gehalten im neuen Israelitischen Tempel zu Hamburg, Hamburg: Nestler, 1829

- Digitalisat des Exemplars der Harvard University Library

- Gotthold Salomon, Das neue Gebetbuch und seine Verketzerung, Hamburg: 1841

- Caesar Seligmann, Erinnerungen, Erwin Seligmann (ed.), Frankfurt am Main: 1975

- Andreas Brämer, Judentum und religiöse Reform. Der Hamburger Israelitische Tempel 1817–1938, Hamburg: Dölling und Galitz, 2000. ISBN 3-933374-78-2

- Philipp Lenhard, The Hamburg Temple Controversy. Continuity and a New Beginning in Dibere Haberith, in: Key Documents of German-Jewish History, September 21, 2017. doi:10.23691/jgo:article-24.en.v1

- Michael A. Meyer, Antwort auf die Moderne, Vienna: Böhlau, 2000. ISBN 978-3-205-98363-7

- Institut für die Geschichte der deutschen Juden, Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Hamburg (eds.), Jüdische Stätten in Hamburg - Karte mit Erläuterungen, 3rd ed., Hamburg: 2001

- Institut für die Geschichte der deutschen Juden (ed.), Das Jüdische Hamburg – ein historisches Nachschlagewerk, Göttingen: 2006

- Did Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy make his Psalm 100 for Hamburg Temple?

- Article Temple

- 1817 establishments in the German Confederation

- 1938 disestablishments in Germany

- 19th-century synagogues in Germany

- Former Reform synagogues in Germany

- Jewish German history

- Jewish organizations established in 1917

- Jews and Judaism in Hamburg

- Synagogues in Hamburg

- Synagogues completed in 1818

- Synagogues completed in 1844

- Synagogues completed in 1931