Le Grand Macabre

| Le Grand Macabre | |

|---|---|

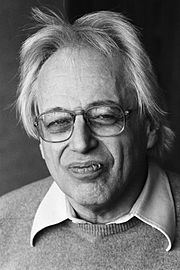

| Opera by György Ligeti | |

György Ligeti in 1984 | |

| Librettist |

|

| Language | German |

| Based on | La Balade du Grand Macabre by Michel de Ghelderode |

| Premiere | 12 April 1978 (in Swedish) Royal Swedish Opera, Stockholm |

Le Grand Macabre (completed 1977, revised 1996) is the third stage production by Hungarian composer György Ligeti, and his only major stage-work. Previously, he had created two absurdist sung "mimodramas" Aventures (compl. 1962) and Nouvelles aventures (1965).

Described as an "anti-anti-opera",[1] Le Grande Macabre has two acts and lasts about 100 minutes. Its libretto, based on Michel de Ghelderode's 1934 play La balade du Grand Macabre, was written by Ligeti himself in collaboration with Michael Meschke, director of the Stockholm Puppet Theatre. The language was German, the title Der grosse Makaber. But for the first production, in 1978, it was translated into Swedish by Meschke under the French title by which it has been known ever since, and under which it was published.[2] Besides these two languages, Le Grand Macabre has been performed in English, French, Italian, Hungarian and Danish, with only a few notes needing to be changed in order to adjust.

The piece contains a dual role for a coloratura soprano that is considered exceptionally difficult; in its premiere the roles were sung by different singers.

Premiere, productions and revision

[edit]Le Grand Macabre was premiered in Stockholm on 12 April 1978.[2] At least 30 productions have followed.[3] For one in Paris in February 1997 (under the auspices of that summer's Salzburg Festival), Ligeti the previous year prepared a revision, making cuts to Scenes 2 and 4, setting some of the originally spoken passages to music and removing others altogether.[2] (As it turned out, the composer was annoyed by the Paris staging, by Peter Sellars,[4] and expressed his displeasure publicly. Sellars, he said, had gone against his desire for ambiguity by explicitly depicting an Apocalypse set in the framework of the Chernobyl Disaster.[3]) This 1996 revised score was published and has become standard. Conductors who have championed Le Grand Macabre include Elgar Howarth,[5] Esa-Pekka Salonen,[6] Michael Boder,[7] Alan Gilbert,[8] Sir Simon Rattle,[9] Thomas Guggeis, who led a new staging by Vasily Barkhatov in November 2023 at Oper Frankfurt,[10][11] and Pablo Heras-Casado, who conducted a different new production a week later at the Vienna State Opera.[12][13]

Roles

[edit]| Role | Voice type | Premiere cast, 12 April 1978 Conductor: Elgar Howarth |

|---|---|---|

| Chef der Gepopo (Chief of the Gepopo, the political police) | high coloratura soprano | Britt-Marie Aruhn |

| Clitoria (Amanda in the revision), lover | soprano | Elisabeth Söderström |

| Spermando (Amando in the revision), lover | mezzo-soprano | Kerstin Meyer |

| Mescalina, wife to Astradamors (and sadist) | mezzo-soprano | Barbro Ericson |

| Fürst Go-Go (Prince Go-Go) | countertenor (or boy treble) | Gunilla Slättegård |

| Piet vom Fass (Piet the Pot) | tenor | Sven-Erik Vikström |

| Nekrotzar (title role) | baritone | Erik Saedén |

| Astradamors, astronomer (and masochist) | bass | Arne Tyrén |

| supporting roles: | ||

| Venus | coloratura soprano | Monika Lavén/Kerstin Wiberg (voice) |

| Ruffiack, ruffian No. 1 | bass | Ragne Wahlroth |

| Schobiack, ruffian No. 2 | baritone | Hans-Olof Söderberg |

| Schabernack, ruffian No. 3 | bass | Lennart Stregård |

| White-party minister | spoken role | Dmitry Cheremeteff/Sven-Erik Vikström (voice) |

| Black-party minister | spoken role | Nils Johansson/Arne Tyrén (voice) |

| Chorus: people of Breughelland; spirits; echo of Venus | ||

The roles of Venus and Chef der Gepopo are occasionally sung by the same coloratura, a dual role that is considered exceptionally difficult.[14] Opera critic Joshua Kosman called it "fiercely demanding".[14]

Musical numbers

[edit]Act 1

[edit]|

Scene 1

|

Scene 2

|

Act 2

[edit]Scene 3

|

|

Orchestration

[edit]Ligeti calls for a very diverse orchestra with a huge assortment of percussion in his opera:

|

|

|

The vast percussion section uses a large variety of domestic items, as well as standard orchestral instruments:

|

|

|

|

|

|

Synopsis

[edit]Act 1

[edit]Scene 1 This opens with a choir of 12 jarring car horns, played with pitches and rhythms specified in the score. These suggest, very abstractly, a barren modern landscape and a traffic jam of sorts. As the overture ends, Piet the Pot, "by trade wine taster", in the country of Breughelland (named after the artist that loosely inspired it), appears to deliver a drunken lament, complete with hiccups. He is accompanied by bassoons, which become the representative instrument for his character. The focus switches to two lovers, Amanda and Amando, who are played by two women even though they represent an opposite-sex couple. Nekrotzar, prince of Hell, hears the lovers from deep inside his tomb and subtly joins their duet. The lovers, confused, discover Piet and become enraged, believing he is spying on them. Piet protests that he "spoke no word, so who spoke? The almighty?" The lovers hide in the tomb to make out.

Nekrotzar emerges, singing a motif, exclaiming "away, you swagpot! Lick the floor, you dog! Squeak out your dying wish, you pig!" Piet responds in kind, with confused drunken statements, until Nekrotzar at last tells him to "Shut up!". Piet must become Death's slave and retrieve all of his "instruments" from the tomb. As Nekrotzar's threats grow deadlier, Piet accepts them with only amused servility, until he is told his throat is to be "wracked with thirst". He objects, because his master had "spoke of death, not punishment!" As Nekrotzar explains his mission, accompanied by percussive tone clusters in the lowest octave of the piano and the orchestra, a choir joins in, admonishing "take warning now, at midnight thou shalt die". Nekrotzar claims he will destroy the earth with a comet God will send to him at midnight. A lone metronome, whose regular tempo ignores that of the rest of the orchestra, joins in. Nekrotzar, making frenzied proclamations, dons his gruesome gear, accompanied by ever more chaotic orchestra, women's choir, and a bass trombone hidden on a balcony, his characteristic instrument. He insists that Piet must be his horse, and Piet's only protest is to give his final cry, "cock-a-doodle-doo!" As they ride off on their quest, the lovers emerge and sing another duet, vowing to ignore the end of time completely and enjoy each other's company.

Scene 2 This begins with a second car horn prelude, which announces a scene change to the household of the court astronomer, Astradamors, and his sadistic wife, Mescalina. "One! Two! Three! Five!" exclaims Mescalina, beating her husband with a whip to the rhythm of shifting, chromatic chords. Astramadors, dressed in drag, unenthusiastically begs for more. She forces him to lift his skirt, and strikes him with a spit. Convinced she has killed him, she begins to mourn, then wonders if he's really dead. She summons a spider, apparently her pet, accompanied by a duo for harpsichord and organ – Regal stops. Astradamors rises, protesting that "spiders always give [him] nausea". As punishment for attempting to fake death, she forces him to take part in an apparent household ritual, a rhythmic dance termed "the Gallopade". This ends with the astronomer kissing her behind, singing "Sweetest Sunday" in falsetto.

Mescalina orders her husband to his telescope. "Observe the stars, left, right. What do you see up there? By the way, can you see the planets? Are they all still there, in the right order?" She addresses Venus with an impassioned plea for a better man, accompanied by an oboe d'amour. As she falls asleep, Astradamors quietly claims he would "plunge the whole universe into damnation, if only to be rid of her!" Right on cue, Nekrotzar arrives, announced by his trumpet, as Venus speaks to Mescalina. Venus informs Mescalina that she has sent "two men", and Nekrotzar steps forward, claiming to be the "well-hung" man Mescalina requested. They perform a stylized lovemaking, as Venus screeches her approval and Piet and Astradamors add their commentary. Nekrotzar suddenly bites Mescalina's neck, killing her, and insists that Piet and his new servant "move this thing [her corpse] out of the way". Driving triplets launch into the trio's humorous rant, "fire and death I bring, burning and shrivelling". Nekrotzar orders his "brigade" to "attention" and they prepare to set off for the royal palace of Prince Go-go. Before doing so, Astradamors destroys everything in his home, proclaiming "at last, I am master in my own house".

Act 2

[edit]Scene 3 This opens with doorbells and alarm clocks, written into the score like the car horns earlier. These seem to represent the rousing of Breughelland as Death approaches. The curtain opens to the throne room, where two politicians dance a lopsided waltz and exchange insults in alphabetical order. "Blackmailer; bloodsucker!" "Charlatan; clodhopper!" "Driveller; dodderer!" "Exorcist; egoist!" "Fraudulent flatterer!" The prince arrives and begs them to put "the interests of the nation" over selfishness. They do so, but force Go-go to mount a giant rocking horse for his "riding lesson". The snare drum leads variations of military march-like music as the politicians contradict one another's advice, finally telling the prince "cavalry charge!" "As in war!" Go-go, who alternately refers to himself in the royal first-person plural, says, "We surrender!" and falls off his horse, to which the black minister says, over-significantly, "thus do dynasties fall". The prince recalls that war is barred in their constitution, but the politicians proclaim the constitution to be mere paper. Their manic laughter is accompanied by burping noises from the low brass. They move on to "posture exercises: how to wear a crown, with dignity". The politicians give him more conflicting advice as Go-go hesitates, accompanied by his characteristic instrument, the harpsichord. When Go-go puts on the crown, the politicians order him to memorize a speech and sign a decree (which raises taxes 100%), arguing over every insignificant issue the whole time. Each time the prince objects, they harmoniously threaten "I shall resign", a possibility of which Go-go seems to be terrified. The prince grows hungry, so the politicians tempt him with a gluttonous feast (to which the fat but boyish monarch sings an impassioned ode). With food in mind, Go-go finally asserts himself and says "we will accept your resignations" after dinner.

Gepopo, chief of espionage, sung by the same soprano who performed Venus, shows up with an army of spies and hangmen. Her high, wailing aria consists of "code language": tumbling, repetitive, hacked up words and phrases. Go-go comprehends the message: the people are planning an insurrection because they fear a great Macabre. The politicians go out on the balcony to try to calm the people with speeches, one after the other, but Go-go laughs at them as they are pelted by shoes, tomatoes, and other objects. He appears on the balcony and the people are enthusiastic, shouting "Our great leader! Our great leader! Go Go Go Go!" for over a minute. Their slow chant is gradually accelerated and its rhythm and intervals transformed, drowning out the Prince's remarks (only his gestures are visible). However, Gepopo receives a dispatch (a comic process in which every spy inspects and authenticates it by pantomime) and warns Go-go with more code language that a comet is drawing closer and a true Macabre is approaching. The politicians try to play it off as alarmism but promptly flee the stage when a solitary figure approaches from the direction of the city gate. Go-go proclaims that he is "master in [his] own house" and calls on "legendary might, hallmark of Go-gos" for the tough times ahead. Gepopo warns the prince to call a guard (in her usual "code" style), but it is only Astradamors, who rushes to greet the prince. The two dance and sing "Huzzah! For all is now in order!" (a false ending), ignoring the people's frantic pleas. A siren wails and a bass trumpet announces danger. Go-go is ordered to go "under the bed, quick!" Nekrotzar wordlessly rides in on the back of Piet as "all Hell follows behind". The processional takes the form of a passacaglia, with a repeating pattern in timpani and low strings (who play a parodic imitation of Movement 4 from Beethoven's Eroica Symphony), a scordatura violin (playing a twisted imitation of Scott Joplin's "The Entertainer"), bassoon, sopranino clarinet, and piccolo marching with the procession, and slowly building material in the orchestra.

"Woe!" exclaims Nekrotzar from the balcony. "Woe! Woe!" respond the terrified people. He presents death prophecies such as "the bodies of men will be singed, and all will be turned into charr'd corpses, and shrink like shriveled heads!" His bass trumpet has been joined on the balcony by a little brass ensemble, which punctuates him with two new motifs. The people, several of whom have been disguised the whole time as audience members in opera clothes, beg for mercy. Piet and Astradamors, who have been looking for an excuse to drink, ask the prince of death to eat Go-go's feast with them, a "right royal-looking restaurant". Piet suggests "before we start to dine, I recommend a drop of wine". The pair, who, as his servants, are unafraid of Nekrotzar, dance around playfully insulting him and encouraging him to drink wine. He does so, intoning "may these, the pressed out juices of my victims, serve to strengthen and sustain me before my necessary deed." The three dissolve into a grotesque dialogue, the timpani and orchestra hammering inscrutable off-beats. Nekrotzar says only "Up!" over and over again as he guzzles wine. Finished drinking and utterly incapacitated, he rants and raves about his achievements. "Demolished great kings and queens in scores / no one could escape my claws / Socrates a poison chalice / Nero a knife in his palace." The string music that played while he killed Mescalina is reiterated. Midnight draws near, but Nekrotzar can't stand up. Go-go emerges from hiding, is introduced to "Tsar Nekro" as "Tsar Go-go", and the four perform stripped-down comedy sketches accompanied by stripped-down music. Nekrotzar tries to mount the rocking horse, commanding "in the name of the Almighty, I smite the world to pieces." He retains only a shred of his formerly terrifying nature, but the end of the world is represented by a rough threnody in strings followed by swelling crescendos and decrescendos in the winds. The comet glows brightly and Saturn falls out of its ring in the stage's brightly lit sky.

Scene 4 Calming chords and low string harmonics are accompanied by prominent harmonica, setting the scene for the post-cataclysmic landscape. Piet and Astradamors, believing they are ghosts, float away into the sky. Go-go emerges and believes he is the only person left alive, but "three soldiers, risen from the grave to plunder, loot, and pillage all the good God gave" emerge. They order the "civilian" to halt, and refuse to believe Go-go's claim that he is the prince and he will give them "high decorations, silver and gold, and relieve [them] of official duties". Nekrotzar emerges, disgruntled, from an upturned cart, but his annoyance and confusion that some people seem to have survived is quickly replaced with terror as Mescalina emerges from the tomb. Rough tone clusters in woodwinds and percussion set off their slapstick chase scene, which is joined by Go-go, the soldiers, and the politicians, dragged in by one of the soldiers on a rope. They proclaim their innocence, but Mescalina accuses them of all kinds of atrocities, and they sling mud back at her. "But who invented the military coup?" "Yes, and who invented mass graves?" There is a massive fast-paced fight, and all collapse. Astradamors and Piet float by, and Go-go invites them for a drink of wine. "We have a thirst, so we are living!" they realize as they sink back to earth. Nekrotzar is defeated; they have all survived. In a very curious mirror canon for strings, he shrinks until he is infinitesimally small and disappears. The Finale features all tonal chords arranged in an unpredictable order. The lovers emerge from the tomb, boasting about what good they did. The entire cast encourages the audience: "Fear not to die, good people all. No-one knows when his hour will fall. Farewell in cheerfulness, farewell!"

Utopia vs. Dystopia

[edit]

An important underlying theme of Ligetiʼs Grand Macabre is that of utopia and dystopia. Traditionally, dystopia and utopia have formed an alternative. Yet, as Andreas Dorschel argues, Ligeti and librettist Michael Meschke enact an intertwinement of dystopia and utopia, in a series of moves and countermoves: (1) Death threatens to eliminate all life. (2) The earth is saved from the fate of the destruction of life – “Death is dead” (II/4). (3) Yet “Breughelland” is and will remain a crude and cruel tyranny. (4) The farcical character of the whole calls into question whether any of the previous moves can be taken seriously. Ligeti/Meschkeʼs subversion of the antinomy of utopia and dystopia, introduced in the opening “Breughellandlied”, turns out to be in the spirit of Piet the Potʼs namesake Pieter Bruegel the Elder, as Dorschelʼs interpretation of his 1567 painting Het Luilekkerland, an inspiration already to de Ghelderode, shows.[15]

Style

[edit]Le Grand Macabre falls at a point when Ligeti's style was undergoing a significant change—apparently effecting a complete break with his approach in the 1960s. From here onward, Ligeti adopts a more eclectic manner, re-examining tonality and modality (in his own words, "non-atonal" music). In the opera, however, he does not forge a new musical language. The music instead is driven by quotation and pastiche, plundering past styles through allusions to Claudio Monteverdi, Gioachino Rossini, and Giuseppe Verdi.[16]

Concert excerpts

[edit]Three arias from the opera were prepared in 1991 for concert performances under the title Mysteries of the Macabre.[17] Versions exist for soprano or for trumpet, accompanied by orchestra, reduced instrumental ensemble, or piano.[18]

Recordings

[edit]- Ligeti, György. Szenen und Zwischenspiele aus der Oper Le Grand Macabre. Recorded 1979. Inga Nielsen (soprano), Olive Fredricks (mezzo), Peter Haage (tenor), Dieter Weller (baritone), Chorus and Orchester of the Danish Radio, Copenhagen, conducted by Elgar Howarth. LP recording. Wergo WER 60 085, Mainz: Wergo, 1980.

- Ligeti, György. Scènes et interludes du Grand Macabre (1978 version, part 1). Inga Nielsen (soprano), Olive Fredricks (mezzosoprano), Peter Haage (tenor), Dieter Weller (baritone), Nouvel Orchestre philharmonique de Radio France, conducted by Gilbert Amy. In Musique de notre temps: repères 1945–1975, CD no. 4, track 3. Adès 14.122–2. [N.p.]: Adès, 1988.

- Ligeti, György. Le Grand Macabre: Oper in zwei Akten (vier Bildern): (1974–1977). Recorded 16 October 1987, sung in German. Dieter Weller (baritone), Penelope Walmsley-Clark (soprano), Olive Fredricks (mezzosoprano), Peter Haage (tenor), the ORF-Choir, Arnold Schoenberg Choir (Erwin Ortner, choir-master), the Gumpoldskirchner Spatzen (Elisabeth Ziegler, choir-master), and the ORF Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Elgar Howarth. Wergo 2-CD set WER 286 170–2 (box); WER 6170-2 (CD 1); WER 6171-2 (CD 2). Mainz: Wergo, 1991.[19]

- Ligeti, György. Le Grand Macabre (1997 version, in four scenes). Recorded live at the Théâtre du Châtelet, Paris, France, 5–13 February 1998. Sibylle Ehlert and Laura Claycomb (sopranos), Charlotte Hellekant and Jard van Nes (mezzosopranos), Derek Lee Ragin (countertenor), Graham Clark and Steven Cole (tenors), Richard Suart, Martin Winkler, Marc Campbell-Griffiths, and Michael Lessiter (baritones), Willard White and Frode Olsen (basses), London Sinfonietta Voices, Philharmonia Orchestra, conducted by Esa-Pekka Salonen. 2-CD set. Sony S2K 62312. György-Ligeti-Edition 8. [N.p.]: Sony Music Entertainment, 1999.[20]

- Deutscher Musikrat. Musik in Deutschland 1950–2000, Musiktheater 7: Experimentelles Musiktheater, CD 2: Meta-Oper. Experimentelles Musiktheater. 1 CD recording. RCA Red Seal BMG Classics 74321 73675 2. Munich: BMG-Ariola, 2004.

- György Ligeti: Le Grand Macabre: Oper in vier Bildern (1974–77, 1996 version, excerpts, recorded 1998). Caroline Stein (soprano: Venus), Gertraud Wagner (mezzosoprano: Mescalina). Brian Galliford (tenor: Piet vom Faß), Monte Jaffe (baritone), Karl Fäth (bass), Niedersächsisches Staatsorchester Hannover, Chor der Niedersächsischen Staatsoper, conducted by Andreas Delfs. (The CD also includes excerpts from Mauricio Kagel's Aus Deutschland, John Cage's Europeras 1 & 2, and Ligeti's Aventures für 3 Sänger und 7 Instrumentalisten.[21]

- Ligeti: Le Grand Macabre (Barcelona 2011) Chris Merritt, Barbara Hannigan, Gran Teatre del Liceu/ La Fura dels Baus/ Arthaus DVD 2012[22]

References

[edit]Footnotes

- ^ Holze, Guido (4 November 2023). "Ligetis Oper Le Grand Macabre hat in Frankfurt Premiere". FAZ.NET (in German). Retrieved 23 November 2023.

- ^ a b c Griffiths, Paul (2002). "Grand Macabre, Le ('The Grand Macabre')". Grove Music Online. revised by Michael Searby (8th ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.O002356. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0.

- ^ a b Everett 2009, p. 29.

- ^ Steinitz, Richard (2003). György Ligeti: Music of the Imagination. Boston: Northeastern University Press. p. 239. ISBN 978-1-55553-551-3. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 0-571-17631-3.

- ^ "Le Grand Macabre". Schott Music (in German). Retrieved 23 November 2023.

- ^ "György Ligeti – Le Grand Macabre – Sibylle Ehlert, Derek Lee Ragin u.a., Philharmonia Orchestra, Esa-Pekka Salonen". rondomagazin.de (in German). Retrieved 23 November 2023.

- ^ "Le Grand Macabre: Interview with Michael Boder". myfidelio. Retrieved 23 November 2023.

- ^ "Alan Gilbert dirigiert »Le Grand Macabre«". Elbphilharmonie Mediathek (in German). Retrieved 23 November 2023.

- ^ "György Ligeti: Le Grand Macabre". Schott Music (in German). 13 February 2017. Retrieved 23 November 2023.

- ^ "Le Grand Macabre – The season, day by day". Oper Frankfurt. Retrieved 23 November 2023.

- ^ "Skurril-realer Weltuntergang: Vasili Barkhatov inszeniert in Frankfurt "Le Grand Macabre"". Das Opernmagazin (in German). 23 November 2023. Retrieved 23 November 2023.

- ^ "Le Grand Macabre". Wiener Staatsoper (in German). Retrieved 23 November 2023.

- ^ "Kritik – "Le Grand Macabre" in Wien: So bunt kann Apokalypse sein!". BR-Klassik (in German). 13 November 2023. Retrieved 23 November 2023.

- ^ a b Kosman, Joshua (1 November 2004). "Opera crackles and leaps with vibrant, madcap and totally unpredictable 'Macabre'". SFGATE. Retrieved 23 January 2024.

- ^ Andreas Dorschel, ‘‘Breughelland’: Subverting the Antinomy of Utopia and Dystopia’, Studia Musicologica 64 (2023), no.s 1–2, pp. 33–42.

- ^ Searby 1997, pp. 9, 11.

- ^ Ligeti, György; Meschke, Michael (2009), Mysteries of the Macabre three arias from the opera "Le grand macabre" = drei Arien aus der Oper "Le grand macabre" : for coloratura soprano or solo trumpet in C and orchestra = für Koloratursopran oder Solo-Trompete in C und Orchester : (1974-77 ; 1992), Mainz: Schott, OCLC 638477987

- ^ "György Ligeti – Le Grand Macabre". Karsten Witt Music Management. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^ Ligeti, György; Meschke, Michael; Weller, Dieter; Walmsley-Clark, Penelope; Fredricks, Olive; Haage, Peter; Puhlamann-Richter, Christa; Smith, Kevin; Krekow, Ude; Davies, Eirian; Prikopa, Herbert; Strachwitz, Ernst Leopold; Leutgeb, Johann; Salzer, Ernst; Modos, Laszlo; Howarth, Elgar; Ghelderode, Michel de; Österreichischer Rundfunk Chor; Arnold-Schönberg-Chor; Gumpoldskirchner Spatzen (Musical group); Österreichischer Rundfunk Symphonie-Orchester (1991), Le grand macabre (in German), Mainz [Germany]: Wergo, OCLC 811337932

- ^ Ligeti, György; Ehlert, Sibylle; Claycomb, Laura; Ragin, Derek Lee; Clark, Graham; Cole, Steven; Solonen, Esa-Pekka; Meschke, Michael; London Sinfonietta Voices; Philharmonia Orchestra (London, England) (2010), Le Grand macabre : opera in four scenes, New York: Sony Classical, OCLC 931896059

- ^ Kagel, Mauricio; Ligeti, György; Deutscher Musikrat (2004), Meta-Oper (in German), [München]: BMG-Ariola, OCLC 177147032

- ^ Ligeti, György; Meschke, Michael; Merritt, Chris; Moraleda, Inés; Puche, Ana; Mechelen, Werner van; Olsen, Frode; Liang, Ning; Hannigan, Barbara; Asawa, Brian; Vas, Francisco; Butteriss, Simon; Boder, Michael; Ollé, Àlex; Carrasco, Valentina; Flores, Alfons; Aleu, Franc; Castells, Lluc; Praet, Peter van; Basso, José Luís.; Bové, Xavi; Mestres, Carles; Ghelderode, Michel de; Unitel Classica (Firm); Gran Teatre del Liceu (Barcelona, Spain); Zweites Deutsches Fernsehen; 3sat (Firm); Théâtre royal de la Monnaie; Teatro dell'opera (Rome, Italy); English National Opera; Arthaus Musik (Firm) (2012), Le grand macabre, [Halle/Saale]: Arthaus Musik, OCLC 811206829

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

Sources

- Everett, Yayoi Uno (Spring 2009). "Signification of Parody and the Grotesque in György Ligeti's Le Grand Macabre". Music Theory Spectrum. 31 (1): 26–52. doi:10.1525/mts.2009.31.1.26.

- Searby, Michael (January 1997). "Ligeti the Postmodernist?" (PDF). Tempo (199): 9–14. doi:10.1017/S0040298200005544. S2CID 143585594.

Further reading

[edit]- Bauer, Amy. 2017. Ligeti's Laments: Nostalgia, Exoticism and the Absolute. Farnham: Ashgate Publishers (cf. chapter 4).

- Bernard, Jonathan W. 1999. "Ligeti's Restoration of Interval and Its Significance for His Later Works". Music Theory Spectrum 21, no. 1 (Spring): 1–31.

- Cohen-Levinas, Danielle. 2004. "Décomposer le text ou comment libérer la langue au XXe siècle". In La traduction des livrets: Aspects théoriques, historiques et pragmatiques, edited by Gottfried R. Marschall and Louis Jambou, 607–612. Musiques/Écritures: Série études. Paris: Presses de l'Université de Paris-Sorbonne. ISBN 2-84050-328-X.

- Delaplace, Joseph. 2003. "Les formes à ostinato dans Le Grand Macabre de György Ligeti: Analyse des matériaux et enjeux de la répétition". Musurgia: Analyse et pratique musicales 10, no. 1:35–56.

- Dibelius, Ulrich. 1989. "Sprache—Gesten—Bilder: Von György Ligetis Aventures zu Le Grand Macabre". MusikTexte: Zeitschrift für Neue Musik, nos. 28–29:63–67.

- Edwards, Peter. 2016. György Ligeti's Le Grand Macabre: Postmodernism, Musico-Dramatic Form and the Grotesque. Abingdon and New York: Routledge. ISBN 1-4724-5698-X

- Fábián, Imre. 1981. "'Ein unendliches Erbarmen mit der Kreatur'. Zu György Ligetis Le Grand Macabre". Österreichische Musikzeitschrift, 36, nos. 10–11 (October–November) 570–572.

- Kostakeva, Maria. 1996. Die imaginäre Gattung: über das musiktheatralische Werk G. Ligetis. Frankfurt am Main and New York: Peter Lang. ISBN 3-631-48680-4.

- Kostakeva, Maria. 2002. "La méthode du persiflage dans l'opéra Le Grand Macabre de György Ligeti". Analyse Musicale, no. 45 (November): 65–73.

- Ligeti, György. 1978. "Zur Entstehung der Oper Le Grand Macabre". Melos/Neue Zeitschrift für Musik 4, no. 2:91–93.

- Ligeti, György. 1997. "À propos de la genèse de mon opéra". L'Avant-scène opéra, no. 180 (November–December): 88–89.

- Lesle, Lutz, and György Ligeti. 1997. "Unflätiger Minister-Gesang im Walzertakt: Lutz Lesle sprach mit György Ligeti vor der Uraufführung seiner revidierten Oper Le Grand Macabre". Neue Zeitschrift für Musik 158, no. 4 (July–August): 34–35.

- Michel, Pierre. 1985. "Les rapports texte/musique chez György Ligeti de Lux aeterna au Grand Macabre". Contrechamps, no. 4 "Opéra" (April): 128–38.

- Roelcke, Eckhard, and György Ligeti. 1997. "Le Grand Macabre: Zwischen Peking-Oper und jüngstem Gericht". Österreichische Musikzeitschrift 52, no. 8 (August): 25–31.

- Sabbe, Herman. 1979. "De dood (van de opera) gaat niet door". Mens en Melodie (February): 55–58.

- Seherr-Thoss, Peter von. 1998. György Ligetis Oper Le Grand Macabre: erste Fassung, Entstehung und Deutung: von der Imagination bis zur Realisation einer musikdramatischen Idee. Hamburger Beiträge zur Musikwissenschaft 47. Eisenach: Verlag der Musikalienhandlung K. D. Wagner. ISBN 3-88979-079-8.

- Toop, Richard. 1999. György Ligeti. Twentieth-Century Composers. London: Phaidon Press. ISBN 0-7148-3795-4.

- Topor, Roland. 1980. Le Grand Macabre: Entwürfe für Bühnenbilder und Kostüme zu György Ligetis Oper. Diogenes Kunst Taschenbuch 23. Zürich: Diogenes. ISBN 3-257-26023-7.

External links

[edit]- "Illusions and Allusions", interview with Ligeti about the opera

- Video of complete performance on YouTube, La Fura dels Baus, with subtitles in Spanish

- Mysteries of the Macabre, 2015 on YouTube, a scene from the opera performed by Barbara Hannigan, Simon Rattle and the London Symphony Orchestra