Metallica (album)

| Metallica | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | August 12, 1991 | |||

| Recorded | October 6, 1990 – June 16, 1991 | |||

| Studio | One on One (Los Angeles, CA) | |||

| Genre | Heavy metal | |||

| Length | 62:40 | |||

| Label | Elektra | |||

| Producer | ||||

| Metallica chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Metallica studio album chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from Metallica | ||||

| ||||

Metallica (commonly known as The Black Album) is the fifth studio album by American heavy metal band Metallica, released on August 12, 1991, through Elektra Records. It was recorded in an eight-month span at One on One Recording Studios in Los Angeles. The recording of the album was troubled, however, and, during production, the band frequently came into conflict with their new producer Bob Rock. The album marked a change in the band's sound from the thrash metal style of the previous four albums to a slower and heavier one rooted in heavy metal.

Metallica promoted Metallica with a series of tours. They also released five singles to promote the album: "Enter Sandman", "The Unforgiven", "Nothing Else Matters", "Wherever I May Roam", and "Sad but True", all of which have been considered to be among the band's best-known songs. The song "Don't Tread on Me" was also issued to rock radio shortly after the album's release but did not receive a commercial single release.

Metallica received widespread critical acclaim and became the band's best-selling album. It debuted at number one in ten countries and spent four consecutive weeks at the top of the Billboard 200, making it Metallica's first album to top the album charts. Metallica is one of the best-selling albums worldwide, and also one of the best-selling albums in the United States since Nielsen SoundScan tracking began. The album was certified 16× platinum by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) in 2012, and has sold over sixteen million copies in the United States, being the first album in the SoundScan era to do so.

Metallica played Metallica in its entirety during the 2012 European Black Album Tour. In 2003, the album was ranked number 255 on Rolling Stone's 500 greatest albums of all time. In December 2019, Metallica became the fourth release in American history to enter the 550 week milestone on the Billboard 200. It also became the second longest-charting traditional title in history, and the second to spend 550 weeks on the album charts.[6]

Background and recording

At the time of Metallica's recording, the band's songs were written mainly by frontman James Hetfield and drummer Lars Ulrich, with Hetfield being the lyricist.[7] The duo frequently composed together at Ulrich's house in Berkeley, California. Several song ideas and concepts were conceived by other members of the band, lead guitarist Kirk Hammett and bassist Jason Newsted.[8] For instance, Newsted wrote the main riff of "My Friend of Misery", which was originally intended to be an instrumental, one of which had been included on every previous Metallica album.[9] The songs were written in two months in mid-1990; the ideas for some of them were originated during the Damaged Justice Tour.[10] Metallica was impressed with Bob Rock's production work on Mötley Crüe's Dr. Feelgood (1989) and decided to hire him to work on their album.[11][12] Initially, the band members were not interested in having Rock producing the album as well, but changed their minds. Ulrich said, "We felt that we still had our best record in us and Bob Rock could help us make it".[12]

Four demos for the album were recorded on August 13, 1990; "Enter Sandman", "The Unforgiven", "Nothing Else Matters" and "Wherever I May Roam." The lead single "Enter Sandman" was the first song to be written and the last to receive lyrics.[8] On October 4, 1990, a demo of "Sad but True" was recorded. In October 1990, Metallica began recording at One on One Recording Studios in Los Angeles, California, to record the album, and also at Little Mountain Sound Studios in Vancouver, British Columbia for about a week.[11] On June 2, 1991, a demo of "Holier Than Thou" was recorded. Hetfield stated about the recording: "What we really wanted was a live feel. In the past, Lars and I constructed the rhythm parts without Kirk and Jason. This time I wanted to try playing as a band unit in the studio. It lightens things up and you get more of a vibe."[13]

Because it was Rock's first time producing a Metallica album, he had the band make the album in different ways; he asked them to record songs collaboratively rather than individually in separate locations.[11] He also suggested recording tracks live and using harmonic vocals for Hetfield.[14] Rock was expecting the production to be "easy" but had trouble working with the band, leading to frequent, engaged arguments with the band members over aspects of the album.[11] Rock wanted Hetfield to write better lyrics and found his experience recording with Metallica disappointing.[11][15][16] Since the band was perfectionist,[9][15] Rock insisted they recorded as many takes as needed to get the sound they wanted.[7] The album was remixed three times and cost US$1 million.[17] The troubled production coincided with Ulrich, Hammett, and Newsted divorcing their wives; Hammett said this influenced their playing because they were "trying to take those feeling of guilt and failure and channel them into the music, to get something positive out of it".[18]

Rock altered Metallica's familiar recording routine and the recording experience was so stressful that Rock briefly swore never to work with the band again.[16] The tension between band and producer was documented in A Year and a Half in the Life of Metallica and Classic Albums: Metallica – Metallica, documentaries that explore the intense recording process that resulted in Metallica.[7][8] Despite the controversies between the band and Rock, he continued to work with Metallica through to the 2003 album St. Anger.[16] After the production of St. Anger (2003), the fourth and final Metallica record Rock would produce, a petition signed by 1,500 fans was posted online in an attempt to encourage the band to prohibit Rock from producing Metallica albums, saying he had too much influence on the band's sound and musical direction.[19] Rock said the petition hurt his children's feelings;[19] he said, "sometimes, even with a great coach, a team keeps losing. You have to get new blood in there."[19]

Composition

According to Robert Palmer of Rolling Stone, "tempos were often slowed down in exchange for slower BPMs, while they expand its music and expressive range".[21][failed verification] The album was a change in Metallica's direction from the thrash metal style of the band's previous four studio albums towards a more commercial, heavy metal sound, but still had characteristics of thrash metal.[22][7][16] Many fans consider the album to be a transition from the often ostentatious compositions of Metallica's previous releases to the slower, divested style of the band's later albums, where "old" and "new" Metallica are distinguished from one another.[21][failed verification] Instruments not usually used by heavy metal bands, such as the cellos in "The Unforgiven" and the orchestra in "Nothing Else Matters", were added at Rock's insistence.[10] Rock also raised the volume of the bass guitar, which had been nearly inaudible on the previous album ...And Justice for All.[14] Newsted said he tried to "create a real rhythm section rather than a one-dimensional sound" with his bass.[13] Ulrich said he tried to avoid the "progressive Peartian paradiddles which became boring to play live" in his drumming and used a basic sound similar to those of The Rolling Stones' Charlie Watts and AC/DC's Phil Rudd.[14]

The band took a simpler approach partly because the members felt the songs on ...And Justice for All were too long and complex. Hetfield said that radio airplay was not their intention, but because they felt "we had pretty much done the longer song format to death," and considered a good change doing songs with just two riffs and "only taking two minutes to get the point across".[13] Ulrich added that the band was feeling a musical insecurity — "We felt inadequate as musicians and as songwriters, That made us go too far, around Master of Puppets and Justice, in the direction of trying to prove ourselves. 'We'll do all this weird-ass shit sideways to prove that we are capable musicians and songwriters'" – and Hetfield added he wanted to avoid getting stale: "Sitting there and worrying about whether people are going to like the album, therefore we have to write a certain kind of song — you just end up writing for someone else. Everyone's different. If everyone was the same, it would be boring as shit."[10]

The lyrics of Metallica written by James Hetfield were more personal and introspective in nature than those of previous Metallica albums; Rock said Hetfield's songwriting became more confident, and that he was inspired by Bob Dylan, Bob Marley and John Lennon.[16] According to Chris True of AllMusic, "Enter Sandman" is about "nightmares and all that come with them".[23] "The God That Failed" dealt with the death of Hetfield's mother from cancer and her Christian science beliefs, which kept her from seeking medical treatment. "Nothing Else Matters" was a love song Hetfield wrote about missing his girlfriend while on tour.[21] Hetfield said the album's lyrical themes were more introspective because he wanted "lyrics that the band could stand behind – but we are four completely different individuals. So the only way to go was in."[24]

Packaging

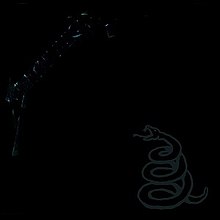

Metallica had many discussions about the album title; the members considered calling it Five or using the title of one of the songs, but eventually chose an eponym because they "wanted to keep it simple."[13] The album's cover depicts the band's logo angled against the upper left corner and a coiled snake derived from the Gadsden flag in the bottom right corner. For the initial release, both emblems were embossed so they could barely be seen against the black background, giving Metallica the nickname "The Black Album". These emblems also appear on the back cover of the album.[7] For later and current releases, both emblems are dark gray so they stand out more prominently. The motto of the Gadsden flag, "Don't Tread on Me", is also the title of a song on the album. A folded, pageless booklet depicts the faces of the band's members against a black background. The lyrics and liner notes are also printed on a grey background. The cover is reminiscent of Spinal Tap's album Smell the Glove, which the band jokingly acknowledged in its documentary A Year and a Half in the Life of Metallica. Members of Spinal Tap appeared on the film and asked Metallica about it, with Lars Ulrich commenting that British rock group Status Quo was the original inspiration as that band's Hello! album cover was also black.[7]

Promotion

Singles

Six tracks on Metallica were released as singles. "Enter Sandman" was released as the lead single on July 29, 1991; it reached number 16 on the Billboard Hot 100 singles chart and was certified Platinum by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA).[25][26] The follow-up single, "Don't Tread on Me", was released promotionally and peaked at number 21 on the Billboard Hot Mainstream Rock Tracks singles chart.[26] "The Unforgiven" was a Top 40 hit; it peaked in the Top 10 in Australia.[27] In 1992, "Nothing Else Matters" was released to more success, reaching number six in the United Kingdom and Ireland.[28][29] The fifth single from the album was also released in 1992; "Wherever I May Roam" peaked at number two on the Mainstream Rock Tracks chart but was less successful on the Hot 100 chart, failing to reach the Top 80.[26] In 1993, "Sad but True" did not repeat the successes of the album's previous singles, charting for one week on the Billboard Hot 100 at 98.[26] Almost all singles were accompanied by music videos; the Wayne Isham-directed "Enter Sandman" promotional film won an MTV Video Music Award for Best Rock Video at the 1992 MTV Video Music Awards.[30]

Tours

In 1991, for the fourth time, Metallica played as part of the Monsters of Rock festival tour. The last concert of the tour was held on September 28, 1991, at Tushino Airfield in Moscow; it was described as "the first free outdoor Western rock concert in Soviet history" and was attended by an estimated 150,000 to 500,000 people.[31][32] Some unofficial estimates put the attendance as high as 1,600,000.[33] The first tour directly intended to support the album, the Wherever We May Roam Tour, included a performance at the Freddie Mercury Tribute Concert, at which Metallica performed a short set list, consisting of "Enter Sandman", "Sad but True" and "Nothing Else Matters", and Hetfield performed the Queen song "Stone Cold Crazy" with John Deacon, Brian May and Roger Taylor of Queen and Tony Iommi of Black Sabbath. At one of the tour's first gigs the floor of the stage collapsed.[34] The January 13 and 14, 1992, shows in San Diego were later released in the box set Live Shit: Binge & Purge,[35] while the tour and the album were documented in the documentary A Year and a Half in the Life of Metallica.[36]

Metallica's Wherever We May Roam Tour also overlapped with Guns N' Roses' Use Your Illusion Tour. Hetfield suffered second and third degree burns to his arms, face, hands, and legs on August 8, 1992, during a Montreal show in the co-headlining Guns N' Roses/Metallica Stadium Tour. The tour included pyrotechnics, which were installed on-stage. Hetfield accidentally walked into a 12-foot (3.7 m) flame shot from a pyrotechnic during a live performance of the introduction of "Fade to Black".[35] The show was cut short shortly after this accident, so that Guns N' Roses began their concert to malicious reactions from fans. Newsted said Hetfield's skin was "bubbling like on The Toxic Avenger".[36] The tour recommenced on August 25 in Phoenix, and although Hetfield could sing, he could not play guitar for the remainder of the tour. Guitar technician John Marshall, who had previously filled in on rhythm guitar and was then playing in Metal Church, played guitar for the recovering Hetfield.[36] Brazilian musician, Andreas Kisser from Sepultura was initially considered for play the tour, but Marshall finally was chosen.[37]

The shows in Mexico City across February and March 1993 during the Nowhere Else to Roam tour were recorded, filmed and later also released as part of the band's first box set,[35][36] which was released in November 1993 and titled Live Shit: Binge & Purge. The collection contained three live CDs, three home videos, and a book filled with riders and letters.[38] Pressings of the box set since November 2002 includes two DVDs, the first one being filmed at San Diego on the Wherever We May Roam Tour, and the latter at Seattle on the Damaged Justice Tour.[36] Binge & Purge was packaged as a cardboard box resembling that of a typical tour equipment transport box. The box set also featured a recreated copy of an access pass to the "Snakepit" part of the tour stage, as well as a cardboard drawing/airbrush stencil for the "Scary Guy" logo.[34] The Mexico City shows were also the first time the band met future member Robert Trujillo, who was in Suicidal Tendencies at the time.[39]

The final tour supporting the album, the Shit Hits the Sheds Tour, included a performance at Woodstock '94 that followed Nine Inch Nails and preceded Aerosmith on August 13 in front of a crowd of 350,000.[40][41] Some songs, such as "Enter Sandman", "Nothing Else Matters" and "Sad but True", became permanent staples of Metallica's concert setlists during these and subsequent tours. Other songs though, such as "Holier Than Thou", "The God That Failed", "Through the Never", and "The Unforgiven" were no longer included in performances after 1995 and would not be played again until the 2000s, when Metallica, with Robert Trujillo on bass, began performing a more extensive back catalog of songs after Trujillo joined the band upon completion of the album St. Anger.[42]

After touring duties for the album were finished, Metallica filed a lawsuit against Elektra Records, which tried to force the record label to terminate the band's contract and give the band ownership of their master recordings. The band based its claim on a section of the California Labor Code that allows employees to be released from a personal services contract after seven years. Metallica had sold 40 million copies worldwide upon the filing of the suit. Metallica had been signed to the label for over a decade but was still operating under the terms of its original 1984 contract, which provided a relatively low 14% royalty rate.[43] The band members said they were taking the action because they were ambivalent about Robert Morgado's refusal to give them another record deal along with Bob Krasnow, who retired from his job at the label shortly afterwards. Elektra responded by counter-suing the band, but in December 1994, Warner Music Group United States chairman Doug Morris offered Metallica a lucrative new deal in exchange for dropping the suit,[44] which was reported to be even more generous than the earlier Krasnow deal. In January 1995, both parties settled out of court with a non-disclosure agreement.[45] Metallica played the album in its entirety during the 2012 European Black Album Tour.[46]

Critical reception

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Chicago Tribune | |

| Encyclopedia of Popular Music | |

| Entertainment Weekly | B+[50] |

| Los Angeles Times | |

| MusicHound Rock | 5/5[52] |

| Pitchfork | 7.7/10[53] |

| Q | |

| Rolling Stone | |

| Select | 4/5[55] |

Metallica was released to widespread acclaim from both heavy metal journalists and mainstream publications, including NME, The New York Times, and The Village Voice.[56] In Entertainment Weekly, David Browne called it "rock's preeminent speed-metal cyclone", and said, "Metallica may have invented a new genre: progressive thrash".[50] Q magazine's Mark Cooper said he found the album's avoidance of metal's typically clumsy metaphors and glossy production refreshing; he said, "Metallica manage to rekindle the kind of intensity that fired the likes of Black Sabbath before metal fell in love with its own cliches".[54] Select magazine's David Cavanagh believed the album lacks artifice and is "disarmingly genuine".[55] In his review for Spin, Alec Foege found the music's harmonies vividly performed and said that Metallica showcase their "newfound versatility" on songs such as "The Unforgiven" and "Holier Than Thou".[57] Robert Palmer, writing in Rolling Stone, said that several songs sound like "hard-rock classics" and that, apart from "Don't Tread on Me", Metallica is an "exemplary album of mature but still kickass rock & roll".[21] In his guide to Metallica's albums up to that point, Greg Kot of the Chicago Tribune recommended the album as "a great place for Metallica neophytes to start, with its more concise songs and explosive production."[48] Jonathan Gold was less enthusiastic in the Los Angeles Times. He said while Metallica embraced pop sensibilities "quite well", there was a sense the group was "no longer in love with the possibilities of its sound" on an album whose difficulty being embraced by the "metal cult" mirrored Bob Dylan going electric in the mid 1960s.[51]

In a retrospective article, Kerrang! said Metallica is the album that "propelled [the band] out of the metal ghetto to true mainstream global rock superstardom".[58] Melody Maker said that as a deliberate departure from the band's thrash style on ...And Justice for All, "Metallica was slower, less complicated, and probably twice as heavy as anything they'd done before".[58] In his review for BBC Music, Sid Smith said that although staunch listeners of the band accused them of selling out, Metallica confidently departed from the style of their previous albums and transitioned "from cult metal gods to bona fide rock stars".[59] Classic Rock called it "the absolute pinnacle of Metallica's long and successful career", and credited the album for inspiring 1990s post-grunge music and convincing the music industry to embrace heavy metal as a genre with mass appeal.[60] AllMusic's Steve Huey believed the massive popularity of Metallica inspired other speed metal bands to also embrace a simpler, less progressive sound. He deemed the record "a good, but not quite great" album, one whose best moments deservedly captured the heavy metal crown, but whose approach also foreshadowed a creative decline for Metallica.[47] Village Voice critic Robert Christgau was less enthusiastic, saying he "put James Hetfield out of his misery in under five plays" and that he "found life getting shorter with every song".[61] In Christgau's Consumer Guide (2000), he later graded the album a "dud", indicating "a bad record whose details rarely merit further thought".[62]

Accolades

Metallica was voted the eighth best album of the year in The Village Voice's annual Pazz & Jop critics poll for 1991.[63] Melody Maker ranked it number 16 in its December 1991 list of the year's best albums.[58] In 1992, the album won a Grammy Award for Best Metal Performance.[64] In 2000 it was voted number 88 in Colin Larkin's All Time Top 1000 Albums.[65] In 2003 and 2012, Rolling Stone ranked Metallica number 255 on its list of the 500 greatest albums of all time[66] and 25th on their 2017 list of "100 Greatest Metal Albums of All Time".[67] Spin ranked it number 52 in its 1999 list of the "90 Greatest Albums of the '90s" and said, "this record's diamond-tipped tuneage stripped the band's melancholy guitar excess down to melodic, radio-ready bullets and ballads".[58] It was included in Q magazine's August 2000 list of the "Best Metal Albums of All Time"; the magazine said the album "transformed them from cult metal heroes into global superstars, bringing a little refinement to their undoubted power".[58] In 1999, eight years after its release, the album won a Billboard Music Award for Catalog Album of the Year.[68]

Commercial performance

You think one day some fucker's gonna tell you, 'You have a number one record in America,' and the whole world will ejaculate. I stood there in my hotel room, and there was this fax that said, 'You're number one.' And it was, like, 'Well, okay.' It was just another fucking fax from the office.

—Lars Ulrich, on Metallica's first number one album[10]

Metallica was released on August 12, 1991,[69] and was the band's first album to debut at number one on the Billboard 200, selling 598,000 copies in its first week. It was certified platinum in two weeks and spent four consecutive weeks atop the Billboard 200.[70][71] Logging over 488 weeks on the Billboard 200, it is the third longest charting album in the Nielsen SoundScan era, behind Pink Floyd's The Dark Side of the Moon and Carole King's Tapestry.[72] In 2009, it surpassed Shania Twain's Come On Over as the best-selling album of the SoundScan era. It became the first album in the SoundScan era to pass 16 million in sales,[73] and with 16.4 million copies sold by 2016, Metallica is the best-selling album in the United States since Nielsen SoundScan tracking began in 1991. Of that sum, 5.8 million were purchased on cassette. The album never sold less than 1,000 copies in a week, and moved a weekly average of 5,000 copies in 2016.[74] Metallica was certified 16× platinum by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) in 2012 for shipping sixteen million copies in the US.[73] Metallica sold 31 million copies worldwide on physical media.[75] All five of Metallica's singles, "Enter Sandman", "The Unforgiven", "Nothing Else Matters", "Wherever I May Roam" and "Sad but True" reached the Billboard Hot 100.[74]

Metallica debuted at number one on the UK Albums Chart,[76] and was certified 2× platinum by the British Phonographic Industry (BPI) for shipping 600,000 copies in the UK.[77] Metallica topped the charts in Australia,[78] Canada,[79] Germany,[80] New Zealand,[81] Norway,[82] the Netherlands,[83] Sweden,[84] and Switzerland.[85] It also reached the top five in Austria,[86] Finland,[87] and Japan,[88] as well as the top 10 in Spain.[89] The album failed to reach the top 20 in Ireland, having peaked at number 27.[90] The Australian Recording Industry Association (ARIA) certified the album 12× platinum.[91] It was given a diamond plaque from the Canadian Recording Industry Association (CRIA)[92] and the Recorded Music NZ (RMNZ)[93] for shipping a million and 150,000 copies, respectively.

Track listing

All lyrics are written by James Hetfield

| No. | Title | Music | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Enter Sandman" |

| 5:34 |

| 2. | "Sad but True" |

| 5:24 |

| 3. | "Holier Than Thou" |

| 3:48 |

| 4. | "The Unforgiven" |

| 6:26 |

| 5. | "Wherever I May Roam" |

| 6:44 |

| 6. | "Don't Tread on Me" |

| 4:01 |

| 7. | "Through the Never" |

| 4:03 |

| 8. | "Nothing Else Matters" |

| 6:30 |

| 9. | "Of Wolf and Man" |

| 4:17 |

| 10. | "The God That Failed" |

| 5:09 |

| 11. | "My Friend of Misery" |

| 6:48 |

| 12. | "The Struggle Within" |

| 3:56 |

| Total length: | 62:40 | ||

Personnel

Credits are adapted from the album's liner notes.[94]

Metallica

- James Hetfield – vocals, rhythm guitar, guitar solo on "Nothing Else Matters", production

- Kirk Hammett – lead guitar

- Jason Newsted – bass guitar

- Lars Ulrich – drums, percussion, production

Additional musicians

- Michael Kamen – orchestral arrangement on "Nothing Else Matters"

Production and design

- Bob Rock – production

- Randy Staub – engineering

- Mike Tacci – engineering

- George Marino – mastering

- Peter Mensch – cover concept

- Don Brautigam – illustration

- Ross Halfin – photography

- Rick Likong – photography

- Rob Ellis – photography

Charts

Weekly charts

|

Year-end charts

Decade-end charts

|

Certifications

| Region | Certification | Certified units/sales |

|---|---|---|

| Argentina (CAPIF)[125] | 5× Platinum | 300,000^ |

| Australia (ARIA)[126] | 12× Platinum | 840,000^ |

| Austria (IFPI Austria)[127] | 2× Platinum | 100,000* |

| Canada (Music Canada)[128] | Diamond | 1,000,000^ |

| Denmark (IFPI Danmark)[129] | 7× Platinum | 400.000^ |

| France (SNEP)[131] | Platinum | 487,500[130] |

| Finland (Musiikkituottajat)[132] | 2× Platinum | 118,956[132] |

| Germany (BVMI)[133] | 4× Platinum | 2,000,000‡ |

| Japan (RIAJ)[134] | 2× Platinum | 400,000^ |

| Italy (FIMI)[135] | Platinum | 100,000* |

| Mexico (AMPROFON)[136] | Gold | 100,000^ |

| Netherlands (NVPI)[137] | 2× Platinum | 200,000^ |

| New Zealand (RMNZ)[138] | 10× Platinum | 150,000^ |

| Norway (IFPI Norway)[139] | 2× Platinum | 100,000* |

| Poland (ZPAV)[140] | Platinum | 20,000‡ |

| Sweden (GLF)[141] | 2× Platinum | 200,000‡ |

| Switzerland (IFPI Switzerland)[142] | 3× Platinum | 150,000^ |

| United Kingdom (BPI)[144] | 2× Platinum | 900,000^[143] |

| United States (RIAA)[146] | 16× Platinum | 16,830,000[145] |

| Summaries | ||

| Worldwide | — | 31,000,000[147] |

|

* Sales figures based on certification alone. | ||

- Their eponymous fifth album, which was released in 1991 and became their first chart-topper. It was nearly three years old by the time OCC chart compilation passed into the hands of Millward Brown in 1994, but has accumulated a chunky 700,676 sales since, and will undoubtedly be a million seller in total.[143]

See also

- List of best-selling albums in Finland

- List of best-selling albums in the United States

- List of best-selling albums

References

- ^ "Enter Sandman". Metallica.com. Retrieved September 7, 2016.

- ^ "The Unforgiven". Metallica.com. Retrieved September 7, 2016.

- ^ "Nothing Else Matters". Metallica.com. Retrieved September 7, 2016.

- ^ "Wherever I May Roam". Metallica.com. Retrieved September 7, 2016.

- ^ "Sad but True". Metallica.com. Retrieved September 7, 2016.

- ^ McIntyre, Hugh. "Metallica Makes History With Their Self-Titled Album". Forbes. Retrieved December 9, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f Adam Dubin, Metallica (James Hetfield, Lars Ulrich, Kirk Hammett, Jason Newsted), Bob Rock, Spinal Tap (1992). A Year and a Half in the Life of Metallica : Part 1 (VHS). Elektra Entertainment.

- ^ a b c d Lars Ulrich (2001). Classic Albums: Metallica – Metallica (DVD). Eagle Rock Entertainment.

- ^ a b Jason Newsted (2001). Classic Albums: Metallica – Metallica (DVD). Eagle Rock Entertainment.

- ^ a b c d Fricke, David (November 14, 1991). "Metallica: From Metal to Main Street". Rolling Stone (617). Archived from the original on March 21, 2009.

- ^ a b c d e Bob Rock (2001). Classic Albums: Metallica – Metallica (DVD). Eagle Rock Entertainment.

- ^ a b Rosen, Craig. The Billboard Book of Number One Albums. Billboard Books, 1996 ISBN 0-8230-7586-9

- ^ a b c d Bienstock, Richard (December 2008). "Metallica: Talkin' Thrash". Guitar World. Archived from the original on June 25, 2016. Retrieved December 11, 2018.

- ^ a b c Mack, Bob (October 1991). "Precious Metal". Spin. 7 (7).

- ^ a b James Hetfield (2001). Classic Albums: Metallica – Metallica (DVD). Eagle Rock Entertainment.

- ^ a b c d e Hodgson, Peter (August 2, 2011). "Metallica Producer: 'Black Album' 'Wasn't Fun'". Gibson Guitar Company. Archived from the original on February 1, 2013. Retrieved August 2, 2011.

- ^ "Metallica timeline February 1990 – August 13, 1991". MTV. Retrieved August 3, 2011.

- ^ Tannenbaum, Rob (April 2001). "Playboy Interview: Metallica". Playboy. Archived from the original on October 26, 2009.

Lars, Jason and I were going through divorces. I was an emotional wreck. I was trying to take those feeling of guilt and failure and channel them into the music, to get something positive out of it.

- ^ a b c "Rock says Metallica fans' petition to dump him was 'hurtful' to his kids". Blabbermouth.net. Retrieved June 8, 2011.

- ^ True, Chris. "Metallica: The Unforgiven". AllMusic. Retrieved June 12, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Palmer, Robert (August 12, 1991). "Metallica Album Review". Rolling Stone. Retrieved June 8, 2016.

- ^ Harrison 2011, p. 60.

- ^ True, Chris. "Enter Sandman Song Review". AllMusic. Retrieved August 27, 2007.

- ^ Tannenbaum, Rob (April 2001). "Playboy Interview: Metallica". Playboy. Archived from the original on October 26, 2009.

- ^ "RIAA Gold and Platinum Searchable Database". RIAA. Archived from the original on June 26, 2007. Retrieved September 1, 2007.

- ^ a b c d "Metallica — Artist Chart History". Billboard. Retrieved April 8, 2007.

- ^ "Australia Top 50 Singles". Retrieved February 26, 2010.

- ^ "Metallica – Nothing Else Matters". Official Charts Company. September 27, 2008. Retrieved November 13, 2010.

- ^ Jaclyn Ward. "The Irish Charts – All there is to know". Irishcharts.ie. Retrieved July 15, 2011.

- ^ "Metallica — Timeline – 1992". Metallica. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved August 28, 2007.

- ^ Schmidt, William E. (September 29, 1991). "Heavy-Metal Groups Shake Moscow". The New York Times. NYTimes.com. Retrieved January 15, 2010.

- ^ "Monsters of Rock hit Moscow". The Eugene Register-Guard. Eugene, Oregon. Associated Press. September 29, 1991. p. 5A. Retrieved January 17, 2010.

- ^ Fitzmaurice, Larry (January 26, 2009). "Sneak Peek: 'Guitar Hero: Metallica". Spin. Retrieved January 29, 2010.

- ^ a b "Snakepit tour". 1999. Archived from the original on October 6, 2011. Retrieved May 8, 2011.

- ^ a b c Metallica (James Hetfield, Lars Ulrich, Kirk Hammett, Jason Newsted) (1992). A Year and a Half in the Life of Metallica : Part 2 (VHS). Elektra Entertainment.

- ^ a b c d e "Metallica timeline August 9, 1992 – November 23, 1993". MTV. Retrieved December 1, 2007.

- ^ "Sepultura's Andreas Kisser: How I Almost Landed Metallica Guitarist Gig". Retrieved January 11, 2018.

- ^ Huey, Steve (November 23, 1993). "Live Shit: Binge & Purge". AllMusic. Retrieved June 8, 2011.

- ^ "Metallica Is A Full Unit Again!!". Metallica.com. February 23, 2003. Archived from the original on June 9, 2008. Retrieved January 24, 2009.

- ^ "Metallica – Woodstock 1994 – 13 August 1994". Woodstock.com. Retrieved August 17, 2010.[permanent dead link]

- ^ DeChillo, Suzanne (October 29, 1994). "Woodstock '94 Site Is Clean and Green". The New York Times. Retrieved January 17, 2010.

- ^ Metallica (January 21, 2004). Some Kind of Monster (Documentary). California: Universal Studios.

- ^ "Heavy Metal Band Sues Record Label". The New York Times. September 28, 1994. Retrieved June 8, 2011.

- ^ Wechsler, Pat; Friedman, Roger D. (December 19–26, 1994). "Heavy Metal Gets the Heavy Bucks". New York. Vol. 27, no. 50. p. 26.

- ^ "Metallica Settles Lawsuit with its Record Label". San Francisco Chronicle. January 6, 1995. Archived from the original on August 11, 2011. Retrieved June 8, 2011.

- ^ "Metallica To Headline Download 2012! | News | Rock Sound". Rocksound.tv. Retrieved February 20, 2012.

- ^ a b Huey, Steve. "Metallica: Metallica". AllMusic. Retrieved December 5, 2007.

- ^ a b Kot, Greg (December 1, 1991). "A Guide to Metallica's Recordings". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved July 28, 2013.

- ^ Larkin, Colin (2006). Encyclopedia of Popular Music. Vol. 5 (4th ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 725. ISBN 0-19-531373-9.

- ^ a b Browne, David (August 16, 1991). "Metallica Review". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved May 26, 2012.

- ^ a b Gold, Jonathan (August 11, 1991). "Advisory to Metallica Fans: It's a Pop Band Now". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 8, 2016.

- ^ Graff, Gary, ed. (1996). "Metallica". MusicHound Rock: The Essential Album Guide. Detroit: Visible Ink Press. ISBN 0787610372.

- ^ Camp, Zoe. "Metallica: Metallica Album Review". pitchfork.com. Retrieved July 9, 2017.

- ^ a b Q, October 1991

- ^ a b Select, September 1991

- ^ Wall, Mick (May 10, 2011). Enter Night: A Biography of Metallica. Macmillan. p. 334. ISBN 1429987030. Retrieved January 28, 2014.

- ^ Foege, Alec (September 1991). "Spins". Spin. New York: 98–99. Retrieved July 28, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e "Metallica LP". CD Universe. Muze. Retrieved July 28, 2013.

- ^ Smith, Sid (2007). "Metallica: Metallica (The Black Album)". BBC Music. Retrieved January 27, 2014.

- ^ "Metallica (Black Album) by Metallica". Classic Rock. August 22, 2011. Retrieved January 27, 2014.

- ^ https://www.robertchristgau.com/xg/pnj/pj91.php

- ^ Christgau, Robert (2000). Christgau's Consumer Guide: Albums of the '90s. Macmillan. pp. xvi, 205. ISBN 0312245602. Retrieved July 28, 2013.

- ^ "The 1991 Pazz & Jop Critics Poll". The Village Voice. New York. March 3, 1992. Archived from the original on July 3, 2011. Retrieved July 28, 2013.

- ^ "Past Winners Search". National Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences. Retrieved May 2, 2012.

- ^ Colin Larkin (2000). All Time Top 1000 Albums (3rd ed.). Virgin Books. p. 71. ISBN 0-7535-0493-6.

- ^ "500 Greatest Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. New York. December 11, 2003.

- ^ Spanos, Brittany (June 21, 2017). "100 Greatest Metal Albums of All Time". Rolling Stone. Wenner Media LLC. Retrieved June 21, 2017.

- ^ http://www.mtv.com/news/569986/backstreet-boys-britney-spears-rake-in-billboard-awards/

- ^ "Metallica". Metallica.com. Retrieved September 7, 2016.

- ^ Garcia, Guy D. (October 14, 1991). "Heavy Metal Goes Platinum". Time. Retrieved September 7, 2016.

- ^ Epstein, Dan (August 12, 2016). "Metallica's Black Album: 10 Things You Didn't Know". Rolling Stone. Retrieved September 7, 2016.

- ^ Wiederhorn, Jon (August 12, 2016). "25 Years Ago: Metallica Release The Black Album". Loudwire. Retrieved September 7, 2016.

- ^ a b Caulfield, Keith (May 28, 2014). "Metallica's 'Black Album' Hits 16 Million in Sales". Billboard. Retrieved September 7, 2016.

- ^ a b Christa Titus, Keith Caulfield (August 12, 2016). "7 Fast Chart Facts About Metallica's 'Black Album,' 25 Years Later". Billboard. Retrieved September 7, 2016.

- ^ Perry, Andrew (September 19, 2013). "Metallica interview: 'We can drive this train into a wall if we want'". The Telegraph. Retrieved January 27, 2014.

- ^ "Metallica UK Chart History". Official Charts Company. Retrieved June 7, 2013.

- ^ "British certifications – Metallica". British Phonographic Industry. Type Metallica in the "Search BPI Awards" field and then press Enter.

- ^ "Australian charts portal". Australian charts. Retrieved August 2, 2011.

- ^ "Metallica Top Albums/CDs positions". RPM. Retrieved August 2, 2011.

- ^ "Chartverfolgung Metallica Longplay" (in German). Musicline. Retrieved August 2, 2011.

- ^ "Metallica New Zealand Charting". Retrieved August 2, 2011.

- ^ "Discography Metallica" (in Norwegian). Norwegian charts. Retrieved August 2, 2011.

- ^ "Discography Metallica" (in Dutch). Dutch charts. Retrieved August 2, 2011.

- ^ "Discography Metallica" (in Swedish). Swedish charts. Retrieved August 2, 2011.

- ^ "Discography Metallica" (in German). Hit parade. Retrieved August 2, 2011.

- ^ "Discography Metallica" (in German). Austrian charts. Retrieved April 8, 2011.

- ^ "Discography Metallica" (in Finnish). Finnish charts. Retrieved April 8, 2011.

- ^ a b "Oricon Chart Database". Oricon. Retrieved April 8, 2011.

- ^ "Hits of the World – Spain". Billboard. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. June 20, 1992. p. 48.

- ^ Hung, Steffen (August 17, 2008). "Metallica discography". irishcharts.com. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ "ARIA Charts – Accreditations – 2015 Albums" (PDF). Australian Recording Industry Association.

- ^ "Canadian certifications – Metallica". Music Canada.

- ^ THE FIELD id (chart number) MUST BE PROVIDED for NEW ZEALAND CERTIFICATION.

- ^ Metallica liner notes. Elektra Records. 1991.

- ^ "Australiancharts.com – Metallica – Metallica". Hung Medien. Retrieved August 27, 2013.

- ^ "Austriancharts.at – Metallica – Metallica" (in German). Hung Medien. Retrieved August 27, 2013.

- ^ "Ultratop.be – Metallica – Metallica" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved August 27, 2013.

- ^ "Metallica Chart History (Canadian Albums)". Billboard. Retrieved August 27, 2013.

- ^ "Danishcharts.dk – Metallica – Metallica". Hung Medien. Retrieved August 27, 2013.

- ^ "Metallica: Metallica" (in Finnish). Musiikkituottajat – IFPI Finland. Retrieved August 27, 2013.

- ^ "Lescharts.com – Metallica – Metallica". Hung Medien. Retrieved August 27, 2013.

- ^ "Longplay-Chartverfolgung at Musicline" (in German). Musicline.de. Phononet GmbH. Retrieved August 27, 2013.

- ^ "GFK Chart-Track Albums: Week {{{week}}}, {{{year}}}". Chart-Track. IRMA. Retrieved August 27, 2013.

- ^ "Mexicancharts.com – Metallica – Metallica". Hung Medien. Retrieved August 27, 2013.

- ^ "Dutchcharts.nl – Metallica – Metallica" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved August 27, 2013.

- ^ "Charts.nz – Metallica – Metallica". Hung Medien. Retrieved August 27, 2013.

- ^ "Norwegiancharts.com – Metallica – Metallica". Hung Medien. Retrieved August 27, 2013.

- ^ "Hits of the World – Spain". Billboard. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. June 20, 1992. p. 48. Retrieved June 10, 2017.

- ^ "Swedishcharts.com – Metallica – Metallica". Hung Medien. Retrieved August 27, 2013.

- ^ "Swisscharts.com – Metallica – Metallica". Hung Medien. Retrieved August 27, 2013.

- ^ "Metallica | Artist | Official Charts". UK Albums Chart. Retrieved August 27, 2013.

- ^ "Metallica Chart History (Billboard 200)". Billboard. Retrieved August 27, 2013.

- ^ "Year-End top-selling albums across all genres, ranked by sales data as compiled by Nielsen SoundScan". Billboard. Prometheus Global Media. 1991. Retrieved August 3, 2015.

- ^ "Year-End top-selling albums across all genres, ranked by sales data as compiled by Nielsen SoundScan". Billboard. Prometheus Global Media. 1992. Retrieved August 27, 2013.

- ^ "Year-End top-selling albums across all genres, ranked by sales data as compiled by Nielsen SoundScan". Billboard. Prometheus Global Media. 1993. Retrieved August 3, 2015.

- ^ "Year-End top-selling albums across all genres, ranked by sales data as compiled by Nielsen SoundScan". Billboard. Prometheus Global Media. 1994. Retrieved August 3, 2015.

- ^ "Year-End top-selling albums across all genres, ranked by sales data as compiled by Nielsen SoundScan". Billboard. Prometheus Global Media. 1995. Retrieved August 3, 2015.

- ^ "Year-End top-selling albums across all genres, ranked by sales data as compiled by Nielsen SoundScan". Billboard. Prometheus Global Media. 1996. Retrieved August 3, 2015.

- ^ "Top Billboard 200 Albums – Year-End 2016". Billboard. Retrieved January 14, 2017.

- ^ "Årslista Album – År 2017" (in Swedish). Sverigetopplistan. Retrieved January 16, 2018.

- ^ "Top Billboard 200 Albums – Year-End 2017". Billboard. Retrieved December 12, 2017.

- ^ "Billboard 200 Albums – Year-End 2018". Billboard. Retrieved December 5, 2018.

- ^ "Årslista Album, 2019". Sverigetopplistan. Retrieved January 14, 2020.

- ^ Mayfield, Geoff (December 25, 1999). 1999 The Year in Music Totally '90s: Diary of a Decade – The listing of Top Pop Albums of the '90s & Hot 100 Singles of the '90s. p. 20. Retrieved August 27, 2013.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ "Discos de oro y platino" (in Spanish). Cámara Argentina de Productores de Fonogramas y Videogramas. Archived from the original on July 6, 2011. Retrieved September 16, 2013.

- ^ "ARIA Charts – Accreditations – 2015 Albums" (PDF). Australian Recording Industry Association.

- ^ "Austrian album certifications – Metallica – Metallica" (in German). IFPI Austria.

- ^ "Canadian album certifications – Metallica – Metallica". Music Canada.

- ^ "Danish album certifications – Metallica – Metallica". IFPI Danmark. Retrieved June 25, 2019. Scroll through the page-list below to obtain certification.

- ^ "Les Meilleures Ventes de CD / Albums "Tout Temps"". Infodisc.fr. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- ^ "French album certifications – Metallica – Metallica" (in French). Syndicat National de l'Édition Phonographique.

- ^ a b "Metallica" (in Finnish). Musiikkituottajat – IFPI Finland. Retrieved November 29, 2013.

- ^ "Gold-/Platin-Datenbank (Metallica; 'Metallica')" (in German). Bundesverband Musikindustrie. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

- ^ "Japanese album certifications – Metallica – Metallica" (in Japanese). Recording Industry Association of Japan.

- ^ "Italian album certifications – Metallica – METALLICA" (in Italian). Federazione Industria Musicale Italiana. Select "Tutti gli anni" in the "Anno" drop-down menu. Type "METALLICA" in the "Filtra" field. Select "Album e Compilation" under "Sezione".

- ^ "Certificaciones" (in Spanish). Asociación Mexicana de Productores de Fonogramas y Videogramas. Retrieved October 4, 2019. Type Metallica in the box under the ARTISTA column heading and Metallica in the box under the TÍTULO column heading.

- ^ "Dutch album certifications – Metallica – Metallica" (in Dutch). Nederlandse Vereniging van Producenten en Importeurs van beeld- en geluidsdragers. Enter Metallica in the "Artiest of titel" box.

- ^ THE FIELD id (chart number) MUST BE PROVIDED for NEW ZEALAND CERTIFICATION.

- ^ "IFPI Norsk platebransje Trofeer 1993–2011" (in Norwegian). IFPI Norway. Retrieved October 4, 2019.

- ^ "Wyróżnienia – Platynowe płyty CD - Archiwum - Przyznane w 2016 roku" (in Polish). Polish Society of the Phonographic Industry.

- ^ certweek IS REQUIRED FOR SWEDISH CERTIFICATIONS.

- ^ "The Official Swiss Charts and Music Community: Awards ('Metallica')". IFPI Switzerland. Hung Medien.

- ^ a b Jones, Alan (November 25, 2016). "Official Charts Analysis: Little Mix top albums chart with Glory Days". Music Week. Intent Media. Retrieved November 25, 2016.

- ^ "British album certifications – Metallica – Metallica". British Phonographic Industry. Select albums in the Format field. Select 2× Platinum in the Certification field. Type Metallica in the "Search BPI Awards" field and then press Enter.

- ^ "Metallica's 'Black Album' Hits Historic 500th Week on Billboard 200 Chart".

- ^ "American album certifications – Metallica – Metallica". Recording Industry Association of America.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

wwsaleswas invoked but never defined (see the help page).