Poverty

This article may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. |

Poverty is the shortage of common things such as food, clothing, shelter and safe drinking water, all of which determine our quality of life. It may also include the lack of access to opportunities such as education and employment which aid the escape from poverty and/or allow one to enjoy the respect of fellow citizens. According to Mollie Orshansky who developed the poverty measurements used by the U.S. government, "to be poor is to be deprived of those goods and services and pleasures which others around us take for granted."[1] Ongoing debates over causes, effects and best ways to measure poverty, directly influence the design and implementation of poverty-reduction programs and are therefore relevant to the fields of public administration and international development.

Although poverty is mainly considered to be undesirable due to the pain and suffering it may cause, in certain spiritual contexts "voluntary poverty," involving the renunciation of material goods, is seen by some as virtuous.

Poverty may affect individuals or groups, and is not confined to the developing nations. Poverty in developed countries is manifest in a set of social problems including homelessness and the persistence of "ghetto" housing clusters.[2]

Etymology

The word "poverty" came from Latin pauper = "poor".

Measuring poverty

About 1/2 of the human population suffers from poverty. Poverty can be measured in terms of absolute or relative poverty. Absolute poverty refers to a set standard which is consistent over time and between countries. An example of an absolute measurement would be the percentage of the population eating less food than is required to sustain the human body (approximately 2000-2500 calories per day for an adult male).

The World Bank defines extreme poverty as living on less than US $1 (PPP) per day, and moderate poverty as less than $2 a day, estimating that "in 2001, 1.1 billion people had consumption levels below $1 a day and 2.7 billion lived on less than $2 a day."[3] The proportion of the developing world's population living in extreme economic poverty fell from 28 percent in 1990 to 21 percent in 2001.[3] Looking at the period 1981-2001, the percentage of the world's population living on less than $1 per day has halved. However, the actual value of US $1 per day has also decreased considerably over those same years.

Most of this improvement has occurred in East and South Asia.[4] In East Asia the World Bank reported that "The poverty headcount rate at the $2-a-day level is estimated to have fallen to about 27 percent [in 2007], down from 29.5 percent in 2006 and 69 percent in 1990."[5]

In Sub-Saharan Africa extreme poverty rose from 41 percent in 1981 to 46 percent in 2001, which combined with growing population increased the number of people living in poverty from 231 million to 318 million.[6]

Other regions have seen little change. In the early 1990s the transition economies of Eastern Europe and Central Asia experienced a sharp drop in income.[7] The collapse of the Soviet Union resulted in catastrophic declines in GDP of about 45% during the 1990–1996 period[8] and poverty in the region had increased more than tenfold.[9]

World Bank data shows that the percentage of the population living in households with consumption or income per person below the poverty line has decreased in each region of the world since 1990:[10][11]

| Region | 1990 | 2002 | 2004 |

|---|---|---|---|

| East Asia and Pacific | 15.40% | 12.33% | 9.07% |

| Europe and Central Asia | 3.60% | 1.28% | 0.95% |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | 9.62% | 9.08% | 8.64% |

| Middle East and North Africa | 2.08% | 1.69% | 1.47% |

| South Asia | 35.04% | 33.44% | 30.84% |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 46.07% | 42.63% | 41.09% |

There are various criticisms of these measurements.[12] Shaohua Chen and Martin Ravallion note that although "a clear trend decline in the percentage of people who are absolutely poor is evident, although with uneven progress across regions...the developing world outside China and India has seen little or no sustained progress in reducing the number of poor".

Since the world's population is increasing, a constant number living in poverty would be associated with a diminshing proportion. Looking at the percentage living on less than $1/day, and if excluding China and India, then this percentage has decreased from 31.35% to 20.70% between 1981 and 2004.[13]

Other human development indicators are also improving. Life expectancy has greatly increased in the developing world since WWII and is starting to close the gap to the developed world where the improvement has been smaller. Even in Sub-Saharan Africa, where most Least Developed Countries are to be found, life expectancy increased from 30 years before World War II to a peak of about 50 years, before the HIV pandemic and other diseases started to force it down to the current level of 47 years. Child mortality has decreased in every developing region of the world[14]. The proportion of the world's population living in countries where per-capita food supplies are less than 2,200 calories (9,200 kilojoules) per day decreased from 56% in the mid-1960s to below 10% by the 1990s. Between 1950 and 1999, global literacy increased from 52% to 81% of the world. Women made up much of the gap: Female literacy as a percentage of male literacy has increased from 59% in 1970 to 80% in 2000. The percentage of children not in the labor force has also risen to over 90% in 2000 from 76% in 1960. There are similar trends for electric power, cars, radios, and telephones per capita, as well as the proportion of the population with access to clean water.[15] The book The Improving State of the World finds that many other indicators have also improved.

Relative poverty views poverty as socially defined and dependent on social context. Income inequality is a relative measure of poverty. A relative measurement would be to compare the total wealth of the poorest one-third of the population with the total wealth of richest 1% of the population. There are several different income inequality metrics. One example is the Gini coefficient.

Income inequality for the world as a whole is diminishing. A 2002 study by Xavier Sala-i-Martin finds that this is driven mainly, but not fully, by the extraordinary growth rate of the incomes of the 1.2 billion Chinese citizens. China, India, the OECD and the rest of middle-income and rich countries are likely to increase their advantage relative to Africa unless it too achieves economic growth; global inequality may rise. [16][17]

The 2007 World Bank report "Global Economic Prospects" predicts that in 2030 the number living on less than the equivalent of $1 a day will fall by half, to about 550 million. An average resident of what we used to call the Third World will live about as well as do residents of the Czech or Slovak republics today. Much of Africa will have difficulty keeping pace with the rest of the developing world and even if conditions there improve in absolute terms, the report warns, Africa in 2030 will be home to a larger proportion of the world's poorest people than it is today.[18]

In many developed countries the official definition of poverty used for statistical purposes is based on relative income. As such many critics argue that poverty statistics measure inequality rather than material deprivation or hardship. For instance, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, 46% of those in "poverty" in the U.S. own their own home (with the average poor person's home having three bedrooms, with one and a half baths, and a garage).[19] Furthermore, the measurements are usually based on a person's yearly income and frequently take no account of total wealth. The main poverty line used in the OECD and the European Union is based on "economic distance", a level of income set at 50% of the median household income. The US poverty line is more arbitrary. It was created in 1963-64 and was based on the dollar costs of the United States Department of Agriculture's "economy food plan" multiplied by a factor of three. The multiplier was based on research showing that food costs then accounted for about one third of the total money income. This one-time calculation has since been annually updated for inflation.[20] Others, such as economist Ellen Frank, argue that the poverty measure is too low as families spend much less of their total budget on food than they did when the measure was established. Further, federal poverty statistics do not account for the widely varying regional differences in non-food costs such as housing, transport, and utilities. [21]

Other aspects

The point is, economic aspects of poverty may focus on material needs, typically including the necessities of daily living, such as food, clothing, shelter, or safe drinking water. Poverty in this sense may be understood as a condition in which a person or community is lacking in the basic needs for a minimum standard of well-being and life, particularly as a result of a persistent lack of income.

Analysis of social aspects of poverty links conditions of scarcity to aspects of the distribution of resources and power in a society and recognizes that poverty may be a function of the diminished "capability" of people to live the kinds of lives they value.[22] The social aspects of poverty may include lack of access to information, education, health care, or political power.[23][24] Poverty may also be understood as an aspect of unequal social status and inequitable social relationships, experienced as social exclusion, dependency, and diminished capacity to participate, or to develop meaningful connections with other people in society.[25][26][27]

The World Bank's "Voices of the Poor," based on research with over 20,000 poor people in 23 countries, identifies a range of factors which poor people identify as part of poverty.[28] These include:

- Precarious livelihoods

- Excluded locations

- Physical limitations

- Gender relationships

- Problems in social relationships

- Lack of security

- Abuse by those in power

- Dis-empowering institutions

- Limited capabilities

- Weak community organizations

David Moore, in his book The World Bank, argues that some analyses of poverty reflect pejorative, sometimes racial, stereotypes of impoverished people as powerless victims and passive recipients of aid programs.[29]

Causes of poverty

Many different factors have been cited to explain why poverty occurs; no single explanation has gained universal acceptance.

Possible factors include:

Economics

- Recession. The decade of the 1930s saw the Great Depression in the United States and many other countries. Over 60% of Americans were categorized as poor by the federal government in 1933. New York social workers reported that 25% of all schoolchildren were malnourished.[31]

- As of late 2007, increased farming for use in biofuels,[32] along with world oil prices at nearly $130 a barrel,[33] has pushed up the price of grain.[34] Food riots have recently taken place in many countries across the world.[35][36][37]

- Capital flight by which the wealthy in a society shift their assets to off-shore tax havens deprives nations of revenue needed to break the vicious cycle of poverty. [38]

- Weakly entrenched formal systems of title to private property are seen by writers such as Hernando de Soto as a limit to economic growth and therefore a cause of poverty. [39]

- Communists see the institution of property rights itself as a cause of poverty.[40]

- Unfair terms of trade, in particular, the very high subsidies to and protective tariffs for agriculture in the developed world. This drains the taxed money and increases the prices for the consumers in developed world; decreases competition and efficiency; prevents exports by more competitive agricultural and other sectors in the developed world due to retaliatory trade barriers; and undermines the very type of industry in which the developing countries do have comparative advantages.[41]

- Tax havens which tax their own citizens and companies but not those from other nations and refuse to disclose information necessary for foreign taxation. This enables large scale political corruption, tax evasion, and organized crime in the foreign nations.[38]

- Unequal distribution of land. [42] Land reform is one solution.

Governance

- Lacking democracy in poor countries: "The records when we look at social dimensions of development—access to drinking water, girls' literacy, health care—are even more starkly divergent. For example, in terms of life expectancy, rich democracies typically enjoy life expectancies that are nine years longer than poor autocracies. Opportunities of finishing secondary school are 40 percent higher. Infant mortality rates are 25 percent lower. Agricultural yields are about 25 percent higher, on average, in poor democracies than in poor autocracies—an important fact, given that 70 percent of the population in poor countries is often rural-based.""poor democracies don't spend any more on their health and education sectors as a percentage of GDP than do poor autocracies, nor do they get higher levels of foreign assistance. They don't run up higher levels of budget deficits. They simply manage the resources that they have more effectively." [10]

- Economic inequality: In 2006 the poverty rate for minors in the United States was the highest in the industrialized world, with 21.9% of all minors and 30% of African American minors living below the poverty threshold.[43]

- The governance effectiveness of governments has a major impact on the delivery of socioeconomic outcomes for poor populations[44]

- Weak rule of law can discourage investment and thus perpetuate poverty.[45]

- Poor management of resource revenues can mean that rather than lifting countries out of poverty, revenues from such activities as oil production or gold mining actually leads to a resource curse.

- Failure by governments to provide essential infrastructure worsens poverty.[46][47].

- Poor access to affordable education traps individuals and countries in cycles of poverty.[46]

- High levels of corruption undermine efforts to make a sustainable impact on poverty. In Nigeria, for example, more than $400 billion was stolen from the treasury by Nigeria's leaders between 1960 and 1999.[48][49]

- Welfare states have an effect on poverty reduction. Currently modern, expansive welfare states that ensure economic opportunity, independence and security in a near universal manner are still the exclusive domain of the developed nations,[50] commonly constituting at least 20% of GDP, with the largest Scandinavian welfare states constituting over 40% of GDP.[51] These modern welfare states, which largely arose in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, seeing their greatest expansion in the mid 20th century, and have proven themselves highly effective in reducing relative as well as absolute poverty in all analyzed high-income OECD countries.[52][53][54]

| Country | Absolute poverty rate (threshold set at 40% of U.S. median household income)[52] | Relative poverty rate[53] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-transfer | Post-transfer | Pre-transfer | Post-transfer | |

| Sweden | 23.7 | 5.8 | 14.8 | 4.8 |

| Norway | 9.2 | 1.7 | 12.4 | 4.0 |

| Netherlands | 22.1 | 7.3 | 18.5 | 11.5 |

| Finland | 11.9 | 3.7 | 12.4 | 3.1 |

| Denmark | 26.4 | 5.9 | 17.4 | 4.8 |

| Germany | 15.2 | 4.3 | 9.7 | 5.1 |

| Switzerland | 12.5 | 3.8 | 10.9 | 9.1 |

| Canada | 22.5 | 6.5 | 17.1 | 11.9 |

| France | 36.1 | 9.8 | 21.8 | 6.1 |

| Belgium | 26.8 | 6.0 | 19.5 | 4.1 |

| Australia | 23.3 | 11.9 | 16.2 | 9.2 |

| United Kingdom | 16.8 | 8.7 | 16.4 | 8.2 |

| United States | 21.0 | 11.7 | 17.2 | 15.1 |

| Italy | 30.7 | 14.3 | 19.7 | 9.1 |

Demographics and Social Factors

- Overpopulation and lack of access to birth control methods.[55][56] Note that population growth slows or even become negative as poverty is reduced due to the demographic transition.[57]

- Crime, both white-collar crime and blue-collar crime, including violent gangs and drug cartels.[58][59][60]

- Historical factors, for example imperialism, colonialism[61][62][63] and Post-Communism (at least 50 million children in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union lived in poverty).[64][65]

- Brain drain

- Matthew effect: the phenomenon, widely observed across advanced welfare states, that the middle classes tend to be the main beneficiaries of social benefits and services, even if these are primarily targeted at the poor.

- Cultural causes, which attribute poverty to common patterns of life, learned or shared within a community. For example, Max Weber argued that the Protestant work ethic contributed to economic growth during the industrial revolution.

- War, including civil war, genocide, and democide.[68]

- Discrimination of various kinds, such as age discrimination, stereotyping,[69] gender discrimination, racial discrimination, caste discrimination.[70]

- Individual beliefs, actions and choices.[71] For example, research by Isabell Sawhill, a respected researcher from the Brookings Institute indicates that, in the United States, if any individual follows three rules, their chance of being in poverty shrinks to a statistically insignificant level: (1) Stay in school, don't drop out. (2) Postpone bringing children into the world until marriage. (3) Work, don't quit, keep working, no matter how humble the job. Thus, her research indicates that most poverty is associated statistically with individuals who choose (a) to drop out of school, and /or (b) to have children outside of marriage, and/ or (c) who do not hold a job for long. In short, her research suggests that most poverty is statistically associated with poor or unwise life choices.

Health Care

- Poor access to affordable health care makes individuals less resilient to economic hardship and more vulnerable to poverty.[46]

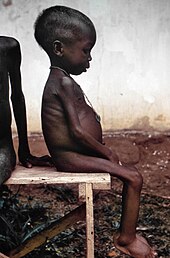

- Inadequate nutrition in childhood, itself an effect of poverty, undermines the ability of individuals to develop their full human capabilities and thus makes them more vulnerable to poverty. Lack of essential minerals such as iodine and iron can impair brain development. It is estimated that 2 billion people (one-third of the total global population) are affected by iodine deficiency, including 285 million 6- to 12-year-old children. In developing countries, it is estimated that 40% of children aged 4 and under suffer from anemia because of insufficient iron in their diets. See also Health and intelligence.[72]

- Disease, specifically diseases of poverty: AIDS,[73] malaria[74] and tuberculosis and others overwhelmingly afflict developing nations, which perpetuate poverty by diverting individual, community, and national health and economic resources from investment and productivity.[75] Further, many tropical nations are affected by parasites like malaria, schistosomiasis, and trypanosomiasis that are not present in temperate climates. The Tsetse fly makes it very difficult to use many animals in agriculture in afflicted regions.

- Clinical depression undermines the resilience of individuals and when not properly treated makes them vulnerable to poverty. [76]

- Similarly substance abuse, including for example alcoholism and drug abuse when not properly treated undermines resilience and can consign people to vicious poverty cycles.[77]

Environmental Factors

- Erosion. Intensive farming often leads to a vicious cycle of exhaustion of soil fertility and decline of agricultural yields and hence, increased poverty.[78]

- Desertification and overgrazing.[79] Approximately 40% of the world's agricultural land is seriously degraded.[80] In Africa, if current trends of soil degradation continue, the continent might be able to feed just 25% of its population by 2025, according to UNU's Ghana-based Institute for Natural Resources in Africa.[81]

- Deforestation as exemplified by the widespread rural poverty in China that began in the early 20th century and is attributed to non-sustainable tree harvesting.[82]

- Natural factors such as climate change.[83] or environment[84] Lower income families suffer the most from climate change; yet on a per capita basis, they contribute the least to climate change [85]

- Geographic factors, for example access to fertile land, fresh water, minerals, energy, and other natural resources, presence or absence of natural features helping or limiting communication, such as mountains, deserts, navigable rivers, or coastline. Historically, geography has prevented or slowed the spread of new technology to areas such as the Americas and Sub-Saharan Africa. The climate also limits what crops and farm animals may be used on similarly fertile lands.[86]

- On the other hand, research on the resource curse has found that countries with an abundance of natural resources creating quick wealth from exports tend to have less long-term prosperity than countries with less of these natural resources.

- Drought and water crisis.[87][88][89]

Cultural Explanations

Many people tend to study and think about the issue of poverty on an individual level. For example, some people from rich nations may wonder “what is wrong with these people, and why can’t they work as hard as we do?” This idea represents the popular view of most in the U.S., which is to blame the poor for their poverty. Sociologist Max Weber was the first to suggest that it was cultural values that affect how economically successful a person would be. In his The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, he argues that the Protestant Reformation led to values that drove people toward worldly achievements, a hard work ethic, and saving to accumulate wealth. Others expanded on Weber’s ideas, producing modernization theory and putting forward a process that all nations should follow to become advanced industrial nations. [90] [91] They believed that to reduce poverty, values and attitudes must be changed.

In recent years, cultural explanations have seem to have made a comeback. The 1985 book Underdevelopment Is a State of Mind has recently been reissued, which claims that Latin American poverty is caused by Catholic values inherited by Latin American countries. [92] Political scientist Samuel Huntington collaborated with Harrison on an edited volume called Culture Matters: How Values Shape Human Progress. At the same time, the World Bank began to pick up the theme of cultural explanations, putting millions of dollars into new research and conferences on the subject, and funding projects in poor countries made to change cultural values.

Criticisms

A large amount of research has rejected these explanations. Researchers have gathered evidence that suggest that values are not as deeply ingrained as most proponents of cultural theories have assumed. Interviews with poor people in the United States indicate that most actually accept the dominant values, but simply find it difficult to live up to them in their current circumstance. Much research has shown that changing economic opportunities explain most of the movement into and out of poverty, as opposed to shifts in values. [93]

Effects of poverty

| This section is reasonably-referenced (and well-intended), but does not meet Wikipedia's standards for tone-- Please help rewrite this section with an Impartial Tone. |

The effects of poverty may also be causes, as listed above, thus creating a "poverty cycle" operating across multiple levels, individual, local, national and global.

Health

Those living in poverty and lacking access to essential health services, suffering hunger or even starvation,[94] experience mental and physical health problems which make it harder for them to improve their situation.[95] One third of deaths - some 18 million people a year or 50,000 per day - are due to poverty-related causes: in total 270 million people, most of them women and children, have died as a result of poverty since 1990.[96] Those living in poverty suffer lower life expectancy. Every year nearly 11 million children living in poverty die before their fifth birthday. Those living in poverty often suffer from hunger.[97] 800 million people go to bed hungry every night.[98] Poverty increases the risk of homelessness.[99] There are over 100 million street children worldwide.[100] Increased risk of drug abuse may also be associated with poverty.[101]

Diseases of poverty reflect the dynamic relationship between poverty and poor health; while such infectious diseases result directly from poverty, they also perpetuate and deepen impoverishment by sapping personal and national health and financial resources. For example, malaria decreases GDP growth by up to 1.3% in some developing nations, and by killing tens of millions in sub-Saharan Africa, AIDS alone threatens “the economies, social structures, and political stability of entire societies”.[102][103]

Education

Research has found that there is a high risk of educational underachievement for children who are from low-income housing circumstances. This often is a process that begins in primary school for some less fortunate children. These children are at a higher risk than other children for retention in their grade, special placements during the school’s hours and even not completing their high school education. [104] There are indeed many explanations for why students tend to drop out of school. For children with low resources, the risk factors are similar to excuses such as juvenile delinquency rates, higher levels of teenage pregnancy, and the economic dependency upon their low income parent or parents. [104]

Families and society who submit low levels of investment in the education and development of less fortunate children end up with less favorable results for the children who see a life of parental employment reduction and low wages. Higher rates of early childbearing with all the connected risks to family, health and well-being are majorly important issues to address since education from preschool to high school are both identifiably meaningful in a life. [104]

Poverty often drastically affects children’s success in school. A child’s “home activities, preferences, mannerisms” must align with the world and in the cases that they do not these students are at a disadvantage in the school and most importantly the classroom. [106] Therefore, it is safe to state that children who live at or below the poverty level will have far less success educationally than children who live above the poverty line. Poor children have a great deal less healthcare and this ultimately results in many absences from the academic year. Additionally, poor children are much more likely to suffer from hunger, fatigue, irritability, headaches, ear infections, and colds. [106] These illnesses could potentially restrict a child or student’s focus and concentration.

Violence

Areas strongly affected by poverty tend to be more violent. In one survey, 67% of children from disadvantaged inner cities said they had witnessed a serious assault, and 33% reported witnessing a homicide.[107] 51% of fifth graders from New Orleans (median income for a household: $27,133) have been found to be victims of violence, compared to 32% in Washington, DC (mean income for a household: $40,127).[108]

Poverty reduction

In politics, the fight against poverty is usually regarded as a social goal and many governments have institutions or departments dedicated to tackling poverty. One of the main debates in the field of poverty reduction is around the question of how actively the state should manage the economy and provide public services to tackle the problem of poverty. In the nineties, international development policies focused on a package of measures known and criticized as the "Washington Consensus" which involved reducing the scope of state activities, and reducing state intervention in the economy, reducing trade barriers and opening economies to foreign investment. Vigorous debate over these issues continues, and most poverty reduction programs attempt to increase both the competitiveness of the economy and the viability of the state.

Poverty Reduction Strategies

Debt Relief

One of the proposed ways to help poor countries that emerged during the 1980's has been debt relief. Given that many less developed nations have gotten themselves into extensive debt to banks and governments from the rich nations, and given that the interest payments on these debts are often more than a country can generate per year in profits from exports, canceling part or all of these debts to may allow poor nations "to get out of the hole".[109] However the effectivness of debt relief is uncertain and whether or not it has lasting effect is disputed. It may not change the underlying conditions that have led to less long-term development in the first place. [110]

Good Governance

According to some social scientists, good governance is one of the most important if not the most important key to economic development and poverty reduction. Good governance means efficient and fair government, government that is less corrupt and works for the long-term interests of the nation as a whole. Researchers at UC Berkely recently developed what they called a "Weberianness scale" which measures aspects of bureaucracies and governments Max Weber described as most important for rational-legal and efficient government over 100 years ago. Comparative research has found that the scale is correlated with higher rates of economic development. [111] With their related concept of good governance World Bank researchers have found much the same: Data from 150 nations have shown several measures of good governance (such as accountability, effectiveness, rule of law, low corruption) to be related to higher rates of economic development. [112]

Examples of good governance leading to economic development and poverty reduction can be seen in countries such as Thailand, Taiwan, Malaysia, South Korea, and Vietnam. These governments are able and willing to protect their people from the negative consequences of foreign corporate exploitation. They tend to have a strong government, also called a hard state or development state, and have leaders who can confront multinationals and demand that they operate to protect their people’s interests. These “hard states” have the will and authority to create and maintain policies that lead to long-term development that helps all their citizens, not just the wealthy. Multinational corporations are regulated so that they follow reasonable standards for pay and labor conditions, pay reasonable taxes to help develop the country, and keep some of the profits in the country, reinvesting them to provide further development. In many other less developed nations around the world, local governments are either too weak to stop foreign corporate exploitation or don’t care, with the corrupt leaders choosing to enrich themselves at the expense of their own people.

Despite all the evidence of the importance of a development state, some international aid agencies have just recently publicly recognized the fact. The United Nations Development Program, for example, published a report in April of 2000 which focused on good governance in poor countries as a key to economic development and overcoming the selfish interests of wealthy elites often behind state actions in developing nations. The report concludes that “Without good governance, reliance on trickle-down economic development and a host of other strategies will not work.” [113]

Despite the promise of such research several questions remain, such as where good governance comes from and how it can be achieved. The comparative analysis of one sociologist [114] suggests that broad historical forces have shaped the likelihood of good governance. Ancient civilizations with more developed government organization before colonialism, as well as elite responsibility, have helped create strong states with the means and efficiency to carry out development policies today. On the other hand strong states are not always the form of political organization most conducive to economic development. Other historical factors, especially the experiences of colonialism for each country, have intervened to make a strong state and/or good governance less likely for some countries, especially in Africa. Another important factor that has been found to affect the quality of institutions and governance was the pattern of colonization (how it took place) and even the identity of colonizing power. International agencies may be able to promote good governance through various policies of intervention in developing nations as indicated in a few African countries, but comparative analysis suggests it may be much more difficult to achieve in most poor nations around the world.[114]

Import Substitution and Export Industries

The most widely used policies of the countries of East and Southeast Asia that have been successful at reducing poverty involve import substitution and the development of export industries. [114] Import substitution simply means attempts to discourage imported goods so that the domestic economy of the less developed country can start making the products itself. Import substitution is the main policy against the problem of structural distortion in the economy of a poor nation. Structural distortion is the lack of jobs and profits obtained in a country where raw materials are extracted and imported to rich nations insead of actually being produced into products.[115]

Problems

There are a few problems with carrying out a long-term policy of import substitution:

- It takes a long time to get such industries operating in the poorer country.

- There is often little capital to start up the industries.

- Wealthy groups within the poor country resist delaying their gratification of consumer goods while waiting until the starup industries are operating in the poor country. Good governance and a strong development state may be needed to implement and follow through with a policy of import substitution.[114]

Once some industries for import substitution are in place the focus can shift to developing export industries. Rather than import goods made in richer countries, less developed countries would prefer rich countries to buy their exported goods. Once they have industries exporting products to richer countires this can reverse the flow of international trade, meaning a favorable balance of trade bringing a net surplus of money into the less developed country. This favorable balance of trade will then accumulate financial resources for further investment in the domestic economy of the less developed nation. A flood of consumer goods such as televisions, stereos, bicycles, and textiles into the United States, Europe, and Japan has helped fuel the economic expansion of Asian tiger economies in recent decades.[116]

Land Redistribution

Many studies have shown that land reform policies that get more land to the cultivators themselves is one of the best ways to reduce world poverty. [117] When peasants and farmers own their own land, farming is often more productive, agriculture is more labor intensive (which creates more farm jobs), and small farmers and peasants are able to keep more of the profits themselves.

Land redistribution has been tried, but has very seldom succeeded. It worked in Japan, but only because the devastation of World War II put the U.S. occupation forces in charge, and General MacArthur was willing to push land reform on a willing Japanese population. [114] During the 1970s the United States under President Carter attempted to impose land reform in Central America. The idea was to give incentives and payments to wealthy landowners, and loans to peasants so they could buy land taken from big haciendas. What seemed like a good idea resulted in political violence and revolution throughout most of Central America. Landowners resisted, peasants who had their hopes raised became angry, and political violence spiraled upward as both sides attacked the other. The results were even more right-wing military coups throughout the region. There was one brief revolutionary government emerging in Nicaragua, but the Reagan administration quickly activitated the CIA to aid the "Contras" who brought down the Sandinista government. [114]

Microloans

One of the most popular of the new technical tools for economic development and poverty reduction are microloans made famous in 1976 by the Grameen Bank in Bangladesh. The idea is to loan small amounts of money to farmers or villages so these people can obtain the things they need to increase their economic rewards. A small pump costing only $50 could make a very big difference in a village without the means of irrigation, for example. A couple of hundred dollars for a small bridge linking a village to a city where it can market farm products is another example. [118][119] A specific example is the Thai government's People's Bank which is making loans of $100 to $300 to help farmers buy equipment or seeds, help street vendors acquire an inventory to sell, or help others set up small shops.

Empowering women

Empowering women has helped some countries increase and sustain economic development. When given more rights and opportunities women begin to receive more education, thus increasing the overall human capital of the country; when given more influence women seem to act more responsibly in helping people in the family or village; and when better educated and more in control of their lives, women are more successful in bringing down rapid population growth becase they have more say in family planning. [120]

Economic growth

The anti-poverty strategy of the World Bank depends heavily on reducing poverty through the promotion of economic growth.[121] The World Bank argues that an overview of many studies shows that:

- Growth is fundamental for poverty reduction, and in principle growth as such does not affect inequality. On average, in developing countries, a 1% increase in average (per capita) incomes reduces the proportion of the population living on less than 1$ a day by about 3%, although other factors are also relevant.

- Growth accompanied by progressive distributional change is better than growth alone.

- High initial income inequality is a brake on poverty reduction. In particular, countries with identical growth rates but lower levels of income inequality experience a more substantial reduction in poverty rates due to economic growth.

- Poverty itself is also likely to be a barrier for poverty reduction; and wealth inequality seems to predict lower future growth rates.[122]

Fair trade

Another approach to alleviating poverty is to implement Fair Trade which advocates the payment of a fair price as well as social and environmental standards in areas related to the production of goods.

Development aid

Most developed nations give development aid to developing countries. The UN target for development aid is 0.7% of GDP; currently only a few nations achieve this. Some think tanks and NGOs have argued that Western monetary aid often only serves to increase poverty and social inequality, either because it is conditioned with the implementation of harmful economic policies in the recipient countries [123], or because it's tied with the importing of products from the donor country over cheaper alternatives,[124] or because foreign aid is seen to be serving the interests of the donor more than the recipient.[125] Critics also argue that some of the foreign aid is stolen by corrupt governments and officials, and that higher aid levels erode the quality of governance. Policy becomes much more oriented toward what will get more aid money than it does towards meeting the needs of the people.[126] Victor Bout, one of the worlds most notorious arms dealers, told the New York Times how he saw firsthand in Angola, Congo and elsewhere "how Western donations to impoverished countries lead to the destruction of social and ecological balance, mutual resentment and eventually war."[127] "Once countries give money, they control you." he says.

Supporters argue that these problems may be solved with better auditing of how the aid is used.[126] Aid from non-governmental organizations may be more effective than governmental aid; this may be because it is better at reaching the poor and better controlled at the grassroots level.[128] As a point of comparison, the annual world military spending is over $1 trillion.[129]

Millennium Development Goals

Eradication of extreme poverty and hunger is the first Millennium Development Goal. One of the targets within this goal is the halving of the proportion of people living in extreme poverty by 2015. In addition to broader approaches, the Sachs Report (for the UN Millennium Project) [130] proposes a series of "quick wins", approaches identified by development experts which would cost relatively little but could have a major constructive effect on world poverty. Some of these "quick wins" are these such as directly assisting local entrepreneurs to grow their businesses and create jobs, access to information on sexual and reproductive health, drugs for AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria, free school meals for schoolchildren, legislation for women’s rights, providing soil nutrients to farmers in sub-Saharan Africa, access to electricity, water and sanitation, upgrading slums and providing land for public housing, among other things.

Successful Cases

East and Southeast Asia

Some of the best prospects for economic growth in the last few decades have been found in East and Southeast Asia. China, South Korea, Japan, Thailand, Taiwan, Vietnam, Malaysia, and Indonesia are developing at high to moderate levels. Thailand, for example, has grown at double-digit rates most years since the early 1980’s. China has been the world leader in economic growth since 2001. It is estimated that it took England around 60 years to double its economy when the Industrial Revolution began. It took the United States around 50 years to double its economy during the American economic take-off in the late nineteenth century. Several East and Southeast Asian countries today have been doubling their economies every 10 years. [131]

It is important to note that in most these Asian countries, it is not just that the rich are getting richer, but the poor are becoming less poor. For example, poverty has dropped dramatically in Thailand. Research in the 1960’s showed that 60 percent of the people in Thailand lived below a poverty level estimated with cost of basic necessities. By 2004, however, similar estimates showed that poverty there was around 13 to 15 percent. Thailand has been shown by some World Bank figures to have had the best record for reducing poverty per increase in GNP of any nation in the world. [132] [133] [134]

In the late 1990’s a study was conducted in which the researchers interviewed people from 24 large factories in Thailand owned by Japanese and American corporations. They found that most of the employees in these corporations made more than the average in Thailand, and substantially more than the $4.40 a day minimum wage in the country at the time. The researchers’ analysis of over 1,000 detailed questionnaires indicated that the employees rate their income and benefits significantly above average compared to Thai-owned factories. They found the working conditions in all 24 companies far from conditions reported about Nike in Southeast Asia. [135]

Explanations

- Some researchers have identified some characteristics of Asian societies that are relatively common and in contrast to Western societies. For example, Asian nations tend to have collectivist rather than individualistic value orientations. This means individual desires and interests are secondary when the needs of a broader group such as the local community, the family, work group, or nation come into conflict with these individual interests. However, not all Asian nations equally value the suppression of the individual, nor do Western nations equally value individualism. There are also differences in Western versus Asian nations on values such as “avoidance of uncertainty,” “power-distance” (power and respect for authority), and a “long-term orientation.” [136] [137]

- The Four Asian Tigers (Taiwan, South Korea, Hong Kong, and Singapore) achieved rapid economic growth in the 1980s with extensive state intervention. [116] As many other researchers have shown, it was Japan that led the way as an Asian late-developing nation with extensive state intervention from the late 1800s to become the second largest economic power in the world after the United States. It was Japan that perfected what is now known as the Asian development model that has been copied in one form or another by Asian nations recently achieving at least some success with economic development. [138]

- In countries such as Thailand, Taiwan, Malaysia, South Korea, and increasingly Vietnam, the governments are able and willing to protect their people from the negative consequences of foreign corporate exploitation. They tend to have a strong government, also called a hard state or development state, and have leaders who can confront multinationals and demand that they operate to protect their people’s interests. These “hard states” have the will and authority to create and maintain policies that lead to long-term development that helps all their citizens, not just the wealthy. Multinational corporations are regulated so that they follow reasonable standards for pay and labor conditions, pay reasonable taxes to help develop the country, and keep some of the profits in the country, reinvesting them to provide further development. In many other periphery nations around the world, local governments are either to weak to stop foreign corporate exploitation or don’t care, with the corrupt leaders choosing to enrich themselves at the expense of their own people.

- One answer to the discrepancies found between multinational corporations in Thailand and the conditions described for Nike workers is that companies such as Wal-Mart, The Gap, or Nike subcontract work to small local factories. These subcontractors remain more invisible, making it more easy to bribe local officials to maintain poor working conditions. When multinational corporations set up business in countries like Malaysia, Taiwan, or Thailand, their visibility makes much less likely employees will have wages and conditions below the standards of living of the country. [139]

- Thailand continued to protect its economy during the 1980’s and 1990’s despite the flood of foreign investment the nation had attracted. Thai bureaucrats started rules such as those demanding a sufficient percentage of domestic content in goods manufactured by foreign companies in Thailand and the 51 percent rule. [140] Under the 51 percent rule, a multinational corporation starting operations in Thailand must form a joint venture with a Thai company. The result is that a Thai company with 51 percent control is better able to keep jobs and profits in the country. Countries such as Thailand have been able to keep foreign investors from leaving because the government has maintained more infrastructure investment to provide good transportation and a rather educated labor force, enhancing productivity.

Barriers to economic development and poverty reduction

For years economists thought that countries throughout the world would follow a the same basic pattern for economic development. It was thought that with some initial capital investment, nations would continue on a path from pre-industrial agrarian societies to industrialization.[141] However, many today hold that these theories are highly misleading when they are applied to developing nations today.[142] [116] [138] [115] [143] The situation faced by developing nations today are very different than those faced by the developed nations when they were going through economic development. Among the new realities facing developing nations are a much larger population, fewer natural resources, and a poorer climate. [144] Most importantly, today’s developed nations did not have other powerful developed nations to contend with during their early process of development. This means that it is much more difficult for poor nations today to achieve economic development. [145]

World-systems perspective

World-systems perspective has generated a great deal of empirical research on poverty and economic growth, mostly showing consistent results. World-systems theory predicts that developing nations (refered to as periphery countries by world-system analysts) have less long-term economic growth when they have extensive multinational corporate investment from core (develeoped) nations. Though there is definitely variance among periphery nations, several studies have shown that many periphery nations that have extensive investment from the core do in fact have less long-term economic growth. [115] [146] [147] [148] [149] [150] [151] These nations are likely to have some short-term economic growth (less than 5 years), but the long-term prospects may be harmed by the kinds of outside aid and investment they have received.

Structural distortion

There seem to be many reasons for harmful effects of core dominance. The first major reason is the problem of structural distortion. In an undistorted economy some natural resources lead to a chain of activity that creates profits, jobs, and growth. For example, consider a core nation with an extensive amount of copper deposits. Jobs are provided and profit is made first from mining the copper. Even more jobs and profits are created when the copper is refined into metal. The metal is used by other corporations to make products, again creating jobs and profits. Next, these products are sold by retail firms, once again resulting in jobs and profits. From this whole process there is a chain of jobs and profits that provide for economic growth as well as revenue that can be used for developing things such as roads, electrical power, and educational institutions within the country.

Imagine now what happens when the copper is mined in a periphery nation with ties to core nations. The copper is mined by native workers, but the metal is shipped to the core where the rest of the chain is completed. The rest of the jobs and profits from the chain of activities are lost to the core nations. This is an example of structural distortion. [115]

Agricultural disruption

Another harmful effect on the economic growth of periphery nations is agricultural disruption. A very important economic activity of periphery nations brought into the modern world-system is export agriculture. Before the modern world-system, agriculture was for local consumption, and there was little incentive for labor-saving farming methods. As a result of these traditional methods of farming and lack of a large market for their products, food was cheaper, some land was left for peasants, and jobs were more plentiful. However, with export agriculture and labor-saving methods of farming, food is more expensive, peasants are pushed off the land so more land may be used to grow products for the world market, and more machines are doing the work, resulting in less jobs. [139] This also causes a higher degree of urbanization as peasants lose their land and jobs and move to the city hoping to find work.[152] Profits are made by a small group of landowners and multinational agribusinesses, with peasants losing jobs, land, and income, which prevents them from being consumers needed for an economy to naturally develop.

Class conflict

A third difficulty for periphery nations are the class conflicts within the nation. Economic and political elites in periphery nations often become more accommodating to corporate elites from core nations that have investments in their country. Of course, these elites in periphery nations receive lucrative profits because of multinational corporate investment. These elites know that the corporations are investing in the country because of low labor costs, low taxes, no unions, and other things such as lax environmental policies, that are favorable to multinational corporate interests. For self-serving elites in periphery nations, it creates a conflict of interest between them and the people. These people, of course, want better wages and more humane working conditions, but if these things are worked on it can mean multinational corporations will leave the country. It is important to realize that the problems mentioned above, structural distortion and agricultural disruption, could be reduced. However, the local elites with the power to change these things do not do so in fear of losing the multinational investment. [139]

Following the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1994, thousands of U.S., Japanese, and European factories moved into Mexico for the free access to the North American market and the low wages. There were about 4,000 of these new factories by 2000. However, by 2002, the factories began moving to nations such as China where wages for factory jobs are as low as $0.25/hour, as opposed to $1.50/hour in Mexico. [153]

Global power imbalances

Another problem for periphery nations has to do with global power imbalances, and the dominating free market ideology pushed by the U.S. and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which is influenced heavily by the U.S. One of the things core nations and agencies such as the IMF fail to understand is that in very critical ways the global economy is very different than it was hundreds of years ago. Free markets then were very rare. Open and free markets can contribute to economic efficiency and competitiveness in the core nations today. However, for periphery nations trying to develop, the same open markets are not provided for them as they are with core nations in the global economy today. Open markets do not always help periphery nations when there are already rich nations over them that are able to distort open markets with billions of dollars in subsidies to their own corporations, which prevent developing industries in periphery nations from having an equal chance of survival. These forces were not around at the time most of the core nations were developing because they were the first ones to become rich. Most of the countries that became rich more than 100 years ago did it with unfree markets that protected their infant industries. Now, the world stratification system provides core nations with the power to enforce the rules of the world economy (and avoid some of these rules themselves), which help the core nations and harm the periphery nations. [139]

Core nations want open markets in other countries, not in their own. Core nations can then buy resources cheaply and sell their own goods, especially in periphery nations. Because of trade barriers placed upon them by core nations, global trade has declined for the poorest nations, despite the fact that it has increased around 60% overall in the past 10 years.

The U.S. has one of the highest tariffs on agricultural imports to protect American agriculture. For example, tariffs on textiles imported into the U.S. are high, unless the clothing is made abroad with U.S.-made textiles by companies such as JC Penny, Target, and The Gap. An African country can export cocoa beans to manufacturers such as Nestle, but if the country processes the beans itself and attempts to sell chocolate to the U.S. or Europe (which would obviously be much more profitable for the country), the tariffs are high. Nestle wants all of the profit that results from processing the cocoa beans and then selling the finished product, but they need the cocoa beans coming from Africa.

Core nations such as the U.S., despite their free market ideology, seem to believe that open markets are best in poor nations rather than than their own. Core nations have the power through organizations such as the World Bank, IMF, and the WTO to protect their industries, but then use their power to make sure periphery nations open their borders to products produced in core nations. It is estimated that the 49 poorest countries in the world lose around $2.5 billion a year due to high tariffs and quotas placed on their products by core nations. For example, Oxfam estimates that the U.S. gets back $7 for every $1 given in aid to Bangladesh because of barriers on imports. They also estimated that rich nations subsidize their own agribusinesses at around $1 billion per day, while the IMF pushes periphery nations to keep their markets open to the food that has flood the market from these countries.[154] When pushed to open their markets to products from core nations backed by subsidies, it is very hard for them to compete.

Voluntary poverty

'Tis the gift to be simple,

'tis the gift to be free,

'tis the gift to come down where you ought to be,

And when we find ourselves in the place just right,

It will be in the valley of love and delight.

— Shaker song.[155]

Among some individuals, such as ascetics, poverty is considered a necessary or desirable condition, which must be embraced in order to reach certain spiritual, moral, or intellectual states. Poverty is often understood to be an essential element of renunciation in religions such as Buddhism and Jainism, whilst in Roman Catholicism it is one of the evangelical counsels. Certain religious orders also take a vow of extreme poverty. For example, the Franciscan orders have traditionally forgone all individual and corporate forms of ownership. While individual ownership of goods and wealth is forbidden for Benedictines, following the Rule of St. Benedict, the monastery itself may possess both goods and money, and throughout history some monasteries have become very rich indeed.[citation needed]

In this context of religious vows, poverty may be understood as a means of self-denial in order to place oneself at the service of others; Pope Honorius III wrote in 1217 that the Dominicans "lived a life of voluntary poverty, exposing themselves to innumerable dangers and sufferings, for the salvation of others". Following Jesus' warning that riches can be like thorns that choke up the good seed of the word (Matthew 13:22), voluntary poverty is often understood by Christians as of benefit to the individual - a form of self-discipline by which one distances oneself from distractions from God.[citation needed]

See also

Organizations and campaigns

|

|

References

- ^ Schwartz, J. E. (2005). Freedom reclaimed: Rediscovering the American vision. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

- ^ Youths' poverty, despair fuel violent unrest in France

- ^ a b The World Bank, 2007, Understanding Poverty [1]

- ^ Shaohua Chen and Martin Ravallion, 2007, "How Have the World's Poorest Fared Since the Early 1980s?" Table 3, p. 28. [2]

- ^ World Bank, 14 November 2007, 'East Asia Remains Robust Despite US Slow Down' [3]

- ^ The Independent, 'Birth rates must be curbed to win war on global poverty', 31 January 2007 [4]

- ^ Worldbank.org reference

- ^ Poverty, crime and migration are acute issues as Eastern European cities continue to grow, A report by UN-Habitat, January 11, 2005

- ^ Study Finds Poverty Deepening in Former Communist Countries, New York Times, October 12, 2000

- ^ World Bank, 2007, Povcalnet Poverty Data [5]

- ^ The data can be replicated using World Bank 2007 Human Development Indicator regional tables, and using the default poverty line of $32.74 per month at 1993 PPP.

- ^ Institute of Social Analysis

- ^ Shaohua Chen and Martin Ravallion, 2007, "How Have the World's Poorest Fared Since the Early 1980s?"[6]

- ^ The Eight Losers of Globalization By Guy Pfeffermann.

- ^ World Development Volume 33, Issue 1 , January 2005, Pages 1-19, Why Are We Worried About Income? Nearly Everything that Matters is Converging

- ^ Global Inequality Fades as the Global Economy Grows 2007 Index of Economic Freedom. Xavier Sala-i-Martin]

- ^ The Disturbing "Rise" of Global Income Inequality by Xavier Sala-i-Martin. 2001

- ^ WORLD BANK HAS GOOD NEWS ABOUT FUTURE By ANDREW CASSEL The Philadelphia Inquirer. Dec. 30, 2006

- ^ Rector, Robert E. and Johnson, Kirk A., Understanding Poverty in America Executive Summary, Heritage Foundation, January 15, 2004 No. 1713

- ^ US Department of Human Services-FAQ Poverty Guidelines and Poverty

- ^ Frank, Ellen, Dr. Dollar: How Is Poverty Defined in Government Statistics? Dollars & Sense magazine, January/February 2006. Accessed April 13, 2008

- ^ Amartya Sen, 1985, Commodities and Capabilities, Amsterdam, New Holland, cited in Siddiqur Rahman Osmani, 2003, Evolving Views on Poverty: Concept, Assessment, and Strategy, [7]

- ^ A Glossary for Social Epidemiology Nancy Krieger, PhD, Harvard School of Public Health

- ^ Journal of Poverty

- ^ H Silver, 1994, social exclusion and social solidarity, in International Labour Review, 133 5-6

- ^ G Simmel, The poor, Social Problems 1965 13

- ^ P Townsend, 1979, Poverty in the UK, Penguin

- ^ {http://www1.worldbank.org/prem/poverty/voices/ Voices of the Poor}

- ^ Chapter on Voices of the Poor in David Moore's edited book The World Bank: Development, Poverty, Hegemony (University of KwaZulu-Natal Press, 2007)-=-

- ^ Slums, Stocks, Stars and the New India, By Erich Follath, SPIEGEL Magazine, 02/28/2007

- ^ Overproduction of Goods, Unequal Distribution of Wealth, High Unemployment, and Massive Poverty, From: President’s Economic Council

- ^ 2008: The year of global food crisis

- ^ The global grain bubble

- ^ The cost of food: Facts and figures

- ^ Riots and hunger feared as demand for grain sends food costs soaring

- ^ Already we have riots, hoarding, panic: the sign of things to come?

- ^ Feed the world? We are fighting a losing battle, UN admits

- ^ a b Western bankers and lawyers 'rob Africa of $150bn every year

- ^ The Mystery of Capital by Hernando de Soto (IMF)

- ^ Marx and Engels, The Communist Manifesto

- ^ Six Reasons to Kill Farm Subsidies and Trade Barriers

- ^ Dagdeviren, Weeks and van der Hoeven(2002) "Poverty Reduction with growth and Redistribution" Development and Change, 33 (3), pp. 383-413 [8]

- ^ U.S. Government Does Relatively Little to Lessen Child Poverty Rates

- ^ Governance Matters IV. [9]

- ^ Ending Mass Poverty by Ian Vásquez

- ^ a b c Global Competitiveness Report 2006, World Economic Forum, Website

- ^ Infrastructure and Poverty Reduction: Cross-country Evidence Hossein Jalilian and John Weiss. 2004.

- ^ Transparency International FAQ

- ^ Nigeria's corruption totals $400 billion

- ^ Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). The three worlds of welfare capitalism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- ^ Barr, N. (2004). The economics of the welfare state. New York: Oxford University Press (USA).

- ^ a b Kenworthy, L. (1999). Do social-welfare policies reduce poverty? A cross-national assessment. Social Forces, 77(3), 1119-1139.

- ^ a b Bradley, D., Huber, E., Moller, S., Nielson, F. & Stephens, J. D. (2003). Determinants of relative poverty in advanced capitalist democracies. American Sociological Review, 68(3), 22-51.

- ^ Smeeding, T. (2005). Public policy, economic inequality, and poverty: The United States in comparative perspective. Social Science Quarterly, 86, 955-983.

- ^ Birth rates 'must be curbed to win war on global poverty The Independent. 31 January 2007.

- ^ Record rise in wheat price prompts UN official to warn that surge in food prices may trigger social unrest in developing countries

- ^ Demographic Transition by Keith Montgomery (Shows how population growth slows with industrialization.)

- ^ Brazil murder rate similar to war zone, data shows

- ^ Mexico: Drug Cartels a Growing Threat

- ^ WHO: 1.6 million die in violence annually

- ^ The Paradox of Africa's Poverty By Tirfe Mammo. 1999. ISBN 1569020493. Gives credit to imperialism/colonialism as a cause as one of two major schools of thought.

- ^ Long-Run Development and the Legacy of Colonialism in Spanish America

- ^ Reflections on Colonial Legacy and Dependency in Indian Vocational Education and Training (VET): a societal and cultural perspective by Madhu Singh

- ^ Child poverty soars in eastern Europe

- ^ Study Finds Poverty Deepening in Former Communist Countries

- ^ India: ‘Hidden Apartheid’ of Discrimination Against Dalits (Human Rights Watch, 13-2-2007)

- ^ India’s human scavengers given a new lease of life, Betwa Sharma: United Nations, The Times, November, 2, 2008

- ^ Ethiopia rejects war criticism

- ^ Ending Poverty in Community (EPIC)

- ^ UN report slams India for caste discrimination

- ^ See, e.g., "The Moral Doctrine of Poverty". Retrieved 2007-01-17.

- ^ Hunger and Malnutrition paper by Jere R Behrman, Harold Alderman and John Hoddinott.

- ^ The long-run economic costs of AIDS: theory and an application to South Africa

- ^ The economic and social burden of malaria.

- ^ Poverty Issues Dominate WHO Regional Meeting

- ^ "Is Depression a Disease of Poverty?". 5 (1).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ ""U.S. Chamber of Commerce Fact Sheet "". Retrieved 2007-01-17.

- ^ Exploitation and Over-exploitation in Societies Past and Present, Brigitta Benzing, Bernd Herrmann

- ^ The Earth Is Shrinking: Advancing Deserts and Rising Seas Squeezing Civilization

- ^ Global food crisis looms as climate change and population growth strip fertile land

- ^ Africa may be able to feed only 25% of its population by 2025

- ^ Forest and Land Management in Imperial China By Nicholas K. Menzies

- ^ Global food crisis looms as climate change and fuel shortages bite

- ^ The Geography of Poverty and Wealth by Jeffrey D. Sachs, Andrew D. Mellinger, and John L. Gallup. From Scientific American magazine

- ^ The poor are hit hardest by climate change By Randy Poplock

- ^ Guns, Germs, and Steel Jared M. Diamond W. W. Norton & Company 1999

- ^ Global Water Shortages May Cause Food Shortages

- ^ Vanishing Himalayan Glaciers Threaten a Billion

- ^ Big melt threatens millions, says UN

- ^ Moore, Wilbert. 1974. Social Change. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hill.

- ^ Parsons, Talcott. 1966. Societies: Evolutionary and Comparative Perspectives. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- ^ Harrison, Lawrence E. 2000. Underdevelopment Is a State of Mind: The Latin American Case. Lanham, MD: Madison Books.

- ^ Kerbo, Harold. 2006. Social Stratification and Inequality: Class Conflict in Historical, Comparative, and Global Perspective, 6th edition New York: McGraw-Hill.

- ^ Forget oil, the new global crisis is food

- ^ Vikram Patel. "Is Depression a Disease of Poverty?". Regional Health Forum WHO South-East Asia Region. 5 (1).

- ^ The World Health Report, World Health Organization (See annex table 2)

- ^ Rising food prices curb aid to global poor

- ^ millenniumcampaign.org

- ^ Study: 744,000 homeless in United States

- ^ Street Children

- ^ Health warning over Russian youth

- ^ Economic costs of malaria

- ^ HIV/AIDS and Poverty

- ^ a b c Huston, A. C. (1991). Children in Poverty: Child Development and Public Policy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Poverty still grips millions in India, BBC News, August 12, 2008

- ^ a b Cite error: The named reference

ANFwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Atkins, M. S., McKay, M., Talbott, E., & Arvantis, P. (1996). "DSM-IV diagnosis of conduct disorder and oppositional defiant disorder: Implications and guidelines for school mental health teams," School Psychology Review, 25, 274-283. Citing: Bell, C. C., & Jenkins, E. J. (1991). "Traumatic stress and children," Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 2, 175-185.

- ^ Atkins, M. S., McKay, M., Talbott, E., & Arvantis, P. (1996). "DSM-IV diagnosis of conduct disorder and oppositional defiant disorder: Implications and guidelines for school mental health teams," School Psychology Review, 25, 274-283. Citing: Osofsky, J. D., Wewers, S., Harm, D. M., & Fick, A. C. (1993). "Chronic community violence: What is happening to our children?," Psychiatry, 56, 36-45; and, Richters, J. E., & Martinez, P (1993). "The NIMH community violence project: Vol. 1. Children as victims of and witnesses to violence," Psychiatry, 56, 7-21.

- ^ World Bank and International Monetary Fund. 2001. Heavily Indebted Poor Countries, Progress Report. Retrieved from http://worldbank.org.

- ^ World Bank and International Monetary Fund. 2001. "Financial Impact of the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries: First 22 Country Cases." Retrieved from http://www.worldbank.org.

- ^ Evans, Peter, and James E. Rauch. 1999. "Bureaucracy and Growth: A Cross-National Analysis of the Effects of 'Weberian' State Structures on Economic Growth." American Sociological Review, 64:748-765.

- ^ Kaufmann, D. "Governance Matters.". World Bank Policy Research Working Paper no. 2196. Washington DC.

{{cite conference}}: Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ United Nations Development Report. 2000. Overcoming Human Poverty: UNDP Poverty Report 2000. New York: United Nations Publications.

- ^ a b c d e f Kerbo, Harold. 2006. World Poverty in the 21st Century. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- ^ a b c d Chase-Dunn, Christopher. 1975. “The Effects of International Economic Dependence on Development and Inequality: A Cross-National Study.” American Sociological Review, 40:720-738. Cite error: The named reference "chasedunn1975" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c Vogel, Ezra F. 1991. The Four Little Dragons: The Spread of Industrialization in East Asia. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

- ^ International Fund for Agricultural Development (2001). Rural Poverty Report 2001: The Challenge of Ending Rural Poverty. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ^ http://microcreditsummit.org

- ^ http://www.grameen-info.org

- ^ World Bank. 2001. Engendering Development--Through Gender Equality in Right, Resources and Voice. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ^ PovertyNet worldbank.org

- ^ Poverty, Growth, and Inequality worldbank.org

- ^ Haiti's rice farmers and poultry growers have suffered greatly since trade barriers were lowered in 1994. By Jane Regan

- ^ Tied Aid Strangling Nations, Says U.N. by Thalif Deen

- ^ US and Foreign Aid, GlobalIssues.org

- ^ a b MYTH: More Foreign Aid Will End Global Poverty

- ^ Arms and the Man New York Times Retrieved on March 25, 2008

- ^ Does Foreign Aid Reduce Poverty? Empirical Evidence from Nongovernmental and Bilateral Aid

- ^ SIPRI Yearbook 2006

- ^ UN Millennium Project

- ^ Kristof, Nicholas D., and Sheryl WuDunn. 2000. Thunder From the East: Portrait of a Rising Asia. New York: Knopf.

- ^ Nabi, Ijaz, and Jayasankur Shivakumer. 2001. Back from the Brink: Thailand’s Response to the 1997 Economic Crisis. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- ^ United Nations Development Report. 1999. Human Development Report of Thailand 1999. Bangkok: Author.

- ^ World Bank. 2000. World Development Report 2000/2001. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Richter, Frank-Jurgen. 2000. The Asian Economic Crisis. New York: Quorum Press.

- ^ Hampden-Turnder, Charles, and Alfons Trompenaars. 1993. The Seven Cultures of Capitalism. New York: Doubleday.

- ^ Hofstede, Geert. 1991. Cultures and Organization: Software of the Mind. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- ^ a b Johnson, Chalmers. 1982. MITI and the Japanese Miracle. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press.

- ^ a b c d Kerbo, Harold. 2006. World Poverty in the 21st Century. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- ^ Muscat, Robert J. 1994. The Fifth Tiger: A Study of Thai Development. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe.

- ^ Rostow, Walter. 1960. The Stages of Economic Development. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Frank, Andre Gunder. 1998. ReOrient: Global Economy in the Asian Age. Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- ^ Portes, Alejandro. 1976. “On the Sociology of National Development: Theories and Issues.” American Journal of Sociology, 85:55-85.

- ^ Myrdal, Gunnar. 1968. Asian Drama: An Inquiry into the Poverty of Nations, 3 vol. New York: Pantheon Books.

- ^ Thurow, Lester. 1991. Head to Head: The Coming Economic Battle Between the United States, Japan, and Europe. New York: Morrow.

- ^ Chase-Dunn, Christopher. 1989. Global Formation: Structures of the World-Economy. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Bornschier, Volker, and Christopher Chase-Dunn. 1985. Transnational Corporations and Underdevelopment. New York: Praeger.

- ^ Bornschier, Volker, Christopher Chase-Dunn, and Richard Rubinson. 1978. “Cross-National Evidence of the Effects of Foreign Investment and Aid on Economic Growth and Inequality: A Survey of Findings and a Reanalysis.” American Journal of Sociology, 84:651-683.

- ^ Snyder, David, and Edward Kick. 1979. “Structural Position in the World System and Economic Growth, 1955-1970: A Multiple Analysis of Transnational Interactions.” American Journal of Sociology, 84:1096-1128.

- ^ Stokes, Randall, and David Jaffee. 1982. “Another Look at the Export of Raw Materials and Economic Growth.” American Sociological Review, 47:402-407.

- ^ Nolan, Patrick D. 1983. “Status in the World Economy and National Structure and Development.” International Journal of Contemporary Sociology, 24:109-120.

- ^ Kentor, Jeffrey. 1981. “Structural Determinants of Peripheral Urbanization: The Effects of International Dependence.” American Sociological Review, 46:201-211.

- ^ http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1P1-53746987.html

- ^ Watkins, Kevin. 2001. “More Hot Air Won’t Bring the World’s Poor in From the Cold.” International Herald Tribune, May 16.

- ^ Simple Gifts

- ^ Campaign to Reduce Poverty in America

- ^ The ONE Campaign

- ^ United Nations Millennium Campaign

- ^ Stand Against Poverty

Further reading

- Agricultural Research, Livelihoods, and Poverty: Studies of Economic and Social Impacts in Six Countries Edited by Michelle Adato and Ruth Meinzen-Dick (2007),Johns Hopkins University Press Food Policy Report (Brief)

- World Bank, Can South Asia End Poverty in a Generation?

- "Educate a Woman, You Educate a Nation" - South Africa Aims to Improve its Education for Girls WNN - Women News Network. Aug. 28, 2007. Lys Anzia

- Atkinson, Anthony B. Poverty in Europe 1998

- Betson, David M., and Jennifer L. Warlick "Alternative Historical Trends in Poverty." American Economic Review 88:348-51. 1998. in JSTOR

- Brady, David "Rethinking the Sociological Measurement of Poverty" Social Forces 81#3 2003, pp. 715-751 Online in Project Muse. Abstract: Reviews shortcomings of the official U.S. measure; examines several theoretical and methodological advances in poverty measurement. Argues that ideal measures of poverty should: (1) measure comparative historical variation effectively; (2) be relative rather than absolute; (3) conceptualize poverty as social exclusion; (4) assess the impact of taxes, transfers, and state benefits; and (5) integrate the depth of poverty and the inequality among the poor. Next, this article evaluates sociological studies published since 1990 for their consideration of these criteria. This article advocates for three alternative poverty indices: the interval measure, the ordinal measure, and the sum of ordinals measure. Finally, using the Luxembourg Income Study, it examines the empirical patterns with these three measures, across advanced capitalist democracies from 1967 to 1997. Estimates of these poverty indices are made available.

- Buhmann, Brigitte, Lee Rainwater, Guenther Schmaus, and Timothy M. Smeeding. 1988. "Equivalence Scales, Well-Being, Inequality, and Poverty: Sensitivity Estimates Across Ten Countries Using the Luxembourg Income Study (LIS) Database." Review of Income and Wealth 34:115-42.

- Cox, W. Michael, and Richard Alm. Myths of Rich and Poor 1999

- Danziger, Sheldon H., and Daniel H. Weinberg. "The Historical Record: Trends in Family Income, Inequality, and Poverty." Pp. 18-50 in Confronting Poverty: Prescriptions for Change, edited by Sheldon H. Danziger, Gary D. Sandefur, and Daniel. H. Weinberg. Russell Sage Foundation. 1994.

- Firebaugh, Glenn. "Empirics of World Income Inequality." American Journal of Sociology (2000) 104:1597-1630. in JSTOR

- Gans, Herbert, J., "The Uses of Poverty: The Poor Pay All", Social Policy, July/August 1971: pp. 20-24

- George, Abraham, Wharton Business School Publications - Why the Fight Against Poverty is Failing: A Contrarian View

- Gordon, David M. Theories of Poverty and Underemployment: Orthodox, Radical, and Dual Labor Market Perspectives. 1972.

- Haveman, Robert H. Poverty Policy and Poverty Research. University of Wisconsin Press 1987.

- John Iceland; Poverty in America: A Handbook University of California Press, 2003

- Alice O'Connor; "Poverty Research and Policy for the Post-Welfare Era" Annual Review of Sociology, 2000

- Osberg, Lars, and Kuan Xu. "International Comparisons of Poverty Intensity: Index Decomposition and Bootstrap Inference." The Journal of Human Resources 2000. 35:51-81.

- Paugam, Serge. "Poverty and Social Exclusion: A Sociological View." Pp. 41-62 in The Future of European Welfare, edited by Martin Rhodes and Yves Meny, 1998.

- Rothman, David J., (editor). "The Almshouse Experience", in series Poverty U.S.A.: The Historical Record, 1971. ISBN 0405030924

- Amartya Sen; Poverty and Famines: An Essay on Entitlement and Deprivation Oxford University Press, 1982

- Sen, Amartya. Development as Freedom (1999)