Anahareo

Anahareo | |

|---|---|

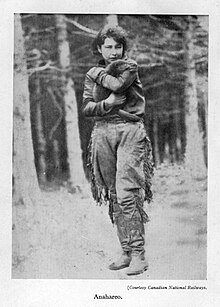

Anahareo (ca. 1928) | |

| Born | Gertrude Bernard June 18, 1906 Mattawa, Ontario, Canada |

| Died | June 17, 1986 (aged 79) Kamloops, British Columbia, Canada |

| Resting place | Ajawaan Lake, Prince Albert National Park, Saskatchewan |

| Known for | animal rights conservation |

| Spouse |

Count Eric Alex Moltke-Huitfeldt

(m. 1939; sep. 1959) |

| Partner | Grey Owl (1926-1936) |

| Children | 3 |

| Awards | Order of Canada |

Gertrude Bernard CM (June 18, 1906 – June 17, 1986), commonly known as Anahareo, was a Canadian writer, animal rights activist and conservationist of Algonquin and Mohawk ancestry. Throughout her life, she challenged cultural stereotypes of First Nations women and proved herself to be "an intrepid, resourceful, and self-reliant woman who could manage on her own in the wilderness and yet was no stranger to the customs and trappings of modern civilization".[1]: 289 At a time when "conservation" stood for increasing the size of animal populations for the sake of hunting and trapping, she, along with Grey Owl, pioneered a new concept – that animals have intrinsic rights and deserve to be treated with respect and compassion. In the later years of her life, she became an outspoken champion of animal rights.

Early life (1906–1925)

[edit]Gertrude Bernard was born on June 18, 1906, in Mattawa, Ontario, where she spent her childhood. Her mother, Mary Nash Ockiping, was Algonquin, while her father, Matthew Bernard, was Algonquin and Mohawk. Her father nicknamed her "Pony" because "she always ran, she never walked". Her mother died when she was four, and she was raised by her paternal grandmother. "Catherine Papineau Bernard, 'Big Grandma', was a respected member of the community who combined a strong Catholic faith with a fierce pride in her heritage and the knowledge and crafts of her people."[1]: 289 Bernard adored her grandmother, who related many memories of her beloved husband and taught her Mohawk customs. Bernard and her descendants were always proud of their Mohawk ancestry. At the age of eleven, her grandmother became too frail to care for her, and one of her aunts, with her family, moved in. Bernard proved to be a rebellious child and grew into a strongly independent young woman.[2]

In 1925 Bernard took a summer job as waitress at the island resort of Camp Wabikon, on Lake Temagami. Her biographer, Kristin Gleeson, writes: "At nineteen she was now a beautiful and energetic young woman with bobbed hair who dressed in riding breeches and shirt, though if the occasion demanded she would apply makeup – the very picture of a modern woman."[2]

She caught the eye of a guest at the resort, a wealthy New Yorker, who offered to pay her school fees. She and her father decided that in the fall she would attend Loretto Abbey, a Roman Catholic boarding school in Toronto.[2] This was not to be, since later in the summer she would meet a guide working at the resort:

A handsome mysterious man, dressed in a buckskin vest, a Hudson Bay belt and moccasins, Archie appeared to Gertie like the dashing daredevil heroes she idolized – Jesse James and Robin Hood. Compared to the bland wealthy vacationers, Archie reeked of adventure and excitement. Gertie found him so fascinating she wasted no time in discovering his name and that he was a guide.[3]

His name was Archibald Belaney and he would later come to be known as Grey Owl. He was 36, almost twice her age, and claimed to be the son of a Scottish man and an Apache woman and to have been born in Mexico.[4]: 9

Life with Grey Owl (1926–1936)

[edit]In February, 1926, forgoing her plans for school, Anahareo (as she would come to be commonly known) joined Belaney near Doucet in the Abitibi region of northwestern Quebec, where he was earning a living as a trapper.[4]: 12 She accompanied Belaney on the trapline and was horrified by what she experienced:

Nothing in her small-town up-bringing had prepared her for the heart-wrenching sight of the frozen corpses of animals who had died in agony while trying desperately to escape from the unyielding metal jaws of the leghold traps. Nor could she bear to watch as Archie used the wooden handle of his axe to club to death those who were still living.[5]: 52

She attempted to make him see the torture that animals suffered when they were caught in traps. According to the account given in Pilgrims of the Wild, Belaney located a beaver lodge, which he knew to be occupied by a mother beaver, and set a trap for her. When the mother beaver was caught, he began to canoe away to the cries of the kittens, which greatly resemble the sound of human infants. She begged him to set the mother free, but, needing the money from the beaver's pelt, he could not be swayed. But the next day he rescued the baby beavers, which the couple adopted and named McGinnis and McGinty.[6]: 27–33

I speedily discovered that I was married to no butterfly, in spite of her modernistic ideas, and found that my companion could swing an axe as well as she could a lip-stick, and was able to put up a tent in good shape, make quick fire, and could rig a tump-line and get a load across in good time, even if she did have to sit down and powder her nose at the other end of the portage. She habitually wore breeches, a custom not at that time so universal amongst women as it is now, and one that I did not in those days look on with any great approval.

—Grey Owl, Pilgrims of the Wild[6]: 16–17

Gertie’s identity as a resourceful, self-reliant woman, at home in the bush yet still at ease with modern ways, emerged. She made her own and Belaney's clothes out of buckskin, canvas, and cloth. She dressed in a distinctive way that was not typical of Indigenous women – in breeches, fringed buckskin jackets and vests, and laceup prospector boots.[1]: 295

Their courtship was at times eventful. In her memoir Devil in Deerskins: My Life with Grey Owl, she claimed that she stabbed Belaney with a knife at one point.[4]: 63 In summer, 1927, Belaney proposed to her. Due to his undissolved marriage to his first wife, Angele Egwuna, the couple could not marry under Canadian law, but the chief of the Lac Simon Band of Indians gave them a "marriage blessing".[7]

In 1928 Belaney and Anahareo, along with the adopted beavers, moved to the area of Cabano in southeastern Quebec, where they were to reside until 1931. Their intention was to set up a beaver colony, where the beavers would be protected and could be studied. It was here that Belaney transformed himself into the writer and lecturer, Grey Owl. The transformation began with the appearance of his first article, "The Passing of the Last Frontier", which was published in 1929 in the English outdoors magazine Country Life. There followed a request from the publisher for the book that would be published in 1931 as The Men of the Last Frontier. He had fully entered into the persona of Grey Owl by January, 1931, when he gave a talk at the annual convention of the Canadian Forestry Association in Montreal. "The event was a huge success. It set the pattern for numerous speeches Grey Owl was to give, dressed in his Indian regalia, with films of his tame beaver to illustrate his stories."[5]: 79

Meanwhile, Anahareo was asserting her independence and bucking stereotypes by embarking on prospecting expeditions in remote areas of northwestern Quebec. She was greatly interested in prospecting, always hoping to stake a claim. This did not pan out, but she did succeed in honing her backcountry skills on these trips: "She portaged canoes, carried packs using tumplines, and built fires and pitched tents like any other skilled bushman. She was an expert with the canoe, able to negotiate rapids and shallows with ease."[1]: 295 She accepted one job that involved hauling 1,320 kilos weight of equipment to a distant lake in winter by dog sled.[8]

In the spring of 1931, Grey Owl accepted an offer of employment from the Parks Branch as the "caretaker of park animals", first at Riding Mountain National Park in Manitoba and then at Prince Albert National Park in Saskatchewan. He and Anahareo, with two new beavers, Jelly Roll and Rawhide, left Quebec, bound for a new life in the west.[9]: 92, 110

The winter of 1931-1932 found Grey Owl preoccupied with writing. Although Anahareo had strongly encouraged him to write, she found it made him "like a zombie". Pregnant with their daughter, Shirley Dawn, who would be born in 1932, she was fed up, later writing "All I heard from Archie that winter was the scratch, scratch of his pen, and arguments against taking a bath. Like a kid, he loathed baths."[9]: 112

Due to her continuing interest in prospecting, she began to study mineralogy.[10] In 1933 she heard of a discovery of gold in Chapleau, Ontario. Leaving Dawn in the care of the Winters family in Prince Albert, she set out on a prospecting trip to try her luck, an event that was reported in the Christian Science Monitor under the headline, "Indian Squaw Turns From Kitchen Duties to Gold Prospecting". She changed her mind and returned home after experiencing five days and nights in a drenching rain that prevented her from going into the woods.[11]

Anahareo went alone on prospecting trips to the remote Churchill River area. The first trip was in the summer of 1933. The second trip lasted an entire year, from the summer of 1934 to the summer of 1935. She travelled by canoe to Wollaston Lake, 550 kilometers north of Prince Albert, and continued farther north to the edge of the Barren Lands. Grey Owl's letters to her betrayed a mixed bag of emotions: admiration for her fiercely independent spirit and courage in making such an arduous trip alone, concern for her safety, envy that she could make a trip into the bush that poor health and the pressure of writing prevented him from making – also irritation that the endeavour cost more than they could afford.[12]

At Grey Owl's request, Anahareo returned from the prospecting trip in the summer of 1935 to help him prepare for the upcoming lecture tour in Great Britain and to look after the beavers in his absence. She sewed his costume for the tour and later wrote:

Archie brought back five moose-hides and about two pounds of beads, but since every stitch of his outfit had to be hand-sewn, with only three weeks to do it in, I told him that I wouldn't have time for beadwork – and besides all that fancy stuff would make him look sissified. To this he answered, 'Do Indians in full regalia look sissified?' 'No, but a bushman would look funny all decorated up.' 'I agree with you there. But I'm not going as a bushman, I'm going as the Indian they expect me to be.'[4]: 173

After Grey Owl's return from the wildly successful lecture tour in Great Britain, the couple's tumultuous ten-year relationship suffered a serious rupture in April 1936, and they agreed to separate for some time. Anahareo received a monthly allowance of $50, almost half of Grey Owl's salary.[9]: 157 They parted for good later that year, probably in September. That was the last time Anahareo ever saw Grey Owl alive.[9]: 163–164

Years of hardship (1937–1959)

[edit]With her daughter Dawn still in the care of a family in Prince Albert, Anahareo made some effort to pursue a film career in Hollywood. (She had previously appeared in two of Grey Owl's "beaver" films: The Beaver People[13] and Pilgrims of the Wild.[14]) But her attempt came to an end in June, 1937, when she gave birth to her second daughter, Ann. The father's name did not appear on the birth certificate and she never publicly stated who the father was. Anahareo found herself in a precarious position financially and socially: Attempts to make use of the backcountry skills she had developed to make money as an experienced guide were fruitless, and she lacked the means to support herself and a new baby. Due to entrenched cultural stereotypes, she also faced particular challenges as an unwed Indigenous mother: The possibility that Ann would be forcibly taken away from her, and she herself institutionalised, were not negligible. After taking shelter for some time in a Salvation Army residence for unwed mothers in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, she gave Ann up for adoption by the Eagles, an Anglo-Canadian couple, who took her to live with them in Calgary. She would grow up with them and only later discover the identity of her biological mother.[15]

After having been away for many months on his second lecture tour, taking in Great Britain, the United States and Canada, Grey Owl returned home, a very ill man. Anahareo was alerted that he was dying in hospital in Prince Albert. She rushed there, but he died before she could see him, on April 13, 1938.

Shortly afterwards, the sensational news broke that he was not half-Indian, as he had claimed to be, but an Englishman born in Hastings, without a trace of Indigenous blood. Anahareo later wrote:

When, finally, I was convinced that Archie was English, I had the awful feeling for all those years I had been married to a ghost, that the man who now lay buried at Ajawaan was someone I had never known, and that Archie had never really existed.[4]: 187

At the invitation of Grey Owl's London publisher, Lovat Dickson, Anahareo travelled to England in 1939 and there met Belaney's mother, Kittie Scott-Brown. Dickson's hope was that "she would, or could, detect in her a drop of Indian blood. Of course, there wasn't a trace".[4]: 187

At Dickson's behest, Anahareo wrote a book of memoirs called My Life With Grey Owl, which was published in 1940. She was dissatisfied with the book, in part because of her lack of control over the content. She complained "The usual portrayal of myself has been that of a sweet, gentle Indian maiden—whispering to the leaves—swaying with the breeze, tra la—. No, no, I’m a rebel really."[16]

In 1939, Anahareo met Eric Moltke, a member of the noble Moltke-Huitfeldt family and formally a count. He had immigrated to Canada from Sweden to start a new life.

Anahareo found Eric handsome, charming and interesting, and he shared her delight in dancing and music. She also valued his regard for her as an equal and the easy manner in which he dismissed race and class. He knew of her past experiences and it made no difference to him. And it could not have escaped her thoughts that with Eric as her husband she would have the extra security that assured that her experience in Saskatoon would not be repeated.[17]

They were married in Winnipeg, Manitoba, where they hoped to find good job opportunities, but ended up doing menial labour. According to Kristin Gleeson, the use of alcohol was a problem for the couple:

Eric, like Grey Owl, was no stranger to drink and by this time it was a familiar part of Anahareo’s life. For Anahareo alcohol was an integral part of any celebration, good time, relaxation or party that enabled her to overcome her shyness and become outgoing, but for Eric it was a daily necessity.[17]

She continues:

In some ways Anahareo had chosen a partner that possessed characteristics that had drawn her to Grey Owl. His charm, wit and an alcohol-fuelled love of a good time were all qualities she had enjoyed with Grey Owl. And with both Grey Owl and Eric she was happy to drink along with them and have fun. With her days in the bush behind her and still raw from the memories from her experiences in Calgary, Saskatoon and Banff, Anahareo’s confidence had diminished. She no longer had trips to the bush to reinforce her sense of capability and strength that marked her for an exceptional woman. She could only get menial jobs that did little to challenge her inquiring mind. With Eric beside Anahareo, alcohol became a way to escape or find confidence.[17]

Moltke enlisted in the army in 1941 and served as a tank driver in WWII. Pregnant with her third daughter, Katherine, Anahareo moved back to Saskatoon, where she rented a small house and lived on a small army wife's pension. Benefiting from a guaranteed income, she brought Dawn from the Winters family in Prince Albert to live with her and Katherine and concentrated on providing a stable family life.[17]

Katherine was four years old and Dawn nearly fourteen when Moltke returned to the family after the war. Having trouble adjusting to civilian life, he drank heavily and was unable to find a job. In 1947 Dawn returned to Prince Albert. Anahareo left Moltke and took a job as cook and housekeeper at a farm in the area. In 1948 Moltke found a job in Canmore, Alberta, and, hoping for a new start, Anahareo and Katherine joined him there.[17]

A friend of Anahareo, Wilna Moore, was fascinated by Grey Owl, and enlisted Anahareo's help in preparing an "exciting narrative of his life". In 1950, she sent the manuscript to Macmillan of Canada, Grey Owl's old publisher. The reviewer reported that "the manuscript itself was 'bulky, untidily put together and poorly typed', and that 'the spelling and punctuation leave much to be desired and the authors frequently use words in their wrong context'." He also questioned "whether certain episodes recorded were really fact or fiction". Macmillan turned down the manuscript.[17]

Anahareo's life with Moltke continued to be troubled, and they periodically separated and then came back together again. To her great joy, she received a visit from her second daughter in 1953. Now spelling her name with an "e", Anne was sixteen and had discovered the identity of her biological mother. Finding life with Moltke untenable, Anahareo, with Katherine, moved back to her childhood home in Mattawa for some time, where she met her family for the first time in nearly thirty years. She eventually decided to return to Moltke in Canmore. Although his family in Sweden had agreed to pay for Katherine to attend boarding school, he refused to give his assent. Moltke suffered a severe workplace accident, and the family moved to Calgary, where he was receiving treatment in hospital. Permanently disabled, unable to work and depressed, he drank heavily. Anahareo was also depressed and tired. When Katherine left for beauty school, she decided to go live with Dawn. Moltke arranged to return to the care of his first wife and the couple permanantly separated on good terms in 1959. He died in 1963.[18]

Success and recognition (1960–1986)

[edit]After moving in with Dawn, Anahareo was diagnosed with a malfunctioning thyroid, the cause of the depression and ill-health from which she had suffered for years. With the improvement brought about by its successful treatment, she began to pursue two projects: a film and a book about Grey Owl. These, she insisted, must portray herself and Grey Owl authentically. She travelled to Toronto, Vancouver and Los Angeles promoting the film project, but with no success. There was little appetite in the film industry for an authentic portrayal of Indigenous Canadians in the 1960s.[16]

Undaunted, Anahareo began writing a book about Grey Owl. Starting in the late 1960s, interest in his life, long on the wane, began to increase, as Kristin Gleeson observed:

As the public became more aware of the negative impact of pollution and the importance of the wilderness to the health of the planet, more Canadians began to view Grey Owl through his role in pioneering wilderness preservation and felt he should be recognized for these achievements.[16]

The Parks Department restored Beaver Lodge, which had fallen into disuse. Anahareo wrote to a fan "I am sure you would feel much better to see it now. Dawn says there is a loneliness there, but the spirits still abid[e]."[16]

Popular and scholarly publications about Grey Owl began to appear. Professor Donald B. Smith published an article on Grey Owl in Ontario History in 1971, a small taste of what was to become his monumental 1990 study From the Land of Shadows: the Making of Grey Owl. The CBC produced a portrait of Grey Owl in 1972. Lovat Dickson brought out a second book of memoirs, Wilderness Man: The Strange Story of Grey Owl, in 1973.[19]

In 1972 Anahareo's book Devil in Deerskins: My Life with Grey Owl was published. It was a popular success, reaching number four on the Toronto Star best seller list. The title was inspired by a conversation she had had with Grey Owl years before, in which he told her he would write a book called "Devil in Deerskins", which would be his last book:

When I asked him why it was going to be his last book he said that after they read that book they wouldn’t read another line from him. And I asked him why and he said Oh, there are things about me that even you don’t know. So, I asked him what he was going to call the book and he was going to call it "Devil in Deerskins" ... and I figured that was what he was going to come out with, to tell all, so, but he didn’t get around to it.[19]

The idea of a film about Grey Owl returned in 1975, when a Toronto film company bought the rights to Dickson's Wilderness Man: The Strange Story of Grey Owl. The film was supposed to feature Marlon Brando as Grey Owl, but the idea never got off the ground. (The company later approached Anahareo for the rights to her book for parts to be included in a scaled-down production of Dickson's story, but she refused. This idea too never got off the ground.) Meanwhile, a Toronto theatre company put on a play entitled Life and Times of Grey Owl. Anahareo's reaction to the opening night performance was scathing: It was "totally unrealistic and the actress bore no resemblance in appearance or mannerisms and definitely not in spirit to her.” She stated: "It turned out to be a parody. Archie must have flipped in his crib.”[19]

Two profiles of Anahareo appeared in the Vancouver Weekend Sun and BC Outdoors in 1980 and 1981, which "succeeded in portraying Anahareo as a living, breathing First Nations woman who could not be easily slotted into any old Aboriginal stereotype... She was a determined woman, with miles of experience, who was committed to her views."[19]

In the remaining years of her life, Anahareo continued to be active in the conservation and animal rights movements. She joined the Society for the Protection of Fur Bearing Animals and campaigned for various issues regarding animal protection such as banning leg hold traps and promoting the use of humane traps. In 1979 she became a member of the Order of Nature of the International League for Animal Rights. The medal she received was engraved with Grey Owl’s words, "kindness is the hallmark of civilization". In 1983 she was presented with the Order of Canada.[19]

During a visit to Grey Owl's birthplace of Hastings to meet the Grey Owl Society, Dawn suddenly died after a long-term battle with diabetes. On June 17, 1986, just a day before her eightieth birthday, Anahareo died in Kamloops, British Columbia. She was buried next to Dawn and Grey Owl above Beaver Lodge.[19]

Anahareo's writings

[edit]- My Life With Grey Owl (1940)

- Devil in Deerskins: My Life with Grey Owl (1972)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Gleeson, Kristin (2010). "Blazing Her Own Trail: Anahareo's Rejection of Euro-Canadian Stereotypes". In Carter, Sarah; McCormack, Patricia (eds.). Recollecting: Lives of Aboriginal Women of the Canadian Northwest and Borderlands. Athabasca, Alberta: Athabasca University Press. ISBN 9781897425824.

- ^ a b c Gleeson, Kristin (2012). "Chapter 1: Childhood and Background". Anahareo: A Wilderness Spirit. Tucson: Fireship Press.

- ^ Gleeson, Kristin (2012). "Chapter 2: Meeting Her Jesse James". Anahareo: A Wilderness Spirit. Tucson: Fireship Press.

- ^ a b c d e f Anahareo [Gertrude Bernard] (2014). Devil in Deerskins: My Life with Grey Owl (Edited and with an Afterword by Sophie McCall ed.). Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press. ISBN 978-0-88755-765-1.

- ^ a b Billinghurst, Jane (1999). The Many Faces of Archie Belaney, Grey Owl. Vancouver: Grey Stone Books. ISBN 9781550546927.

- ^ a b Grey Owl (2010). Pilgrims of the Wild. Toronto: Dundurn Press.

- ^ Gleeson, Kristin (2012). "Chapter 4: Learning Bush Skills". Anahareo: A Wilderness Spirit. Tucson: Fireship Press.

- ^ Gleeson, Kristin (2012). "Chapter 7: The Lure of Prospecting". Anahareo: A Wilderness Spirit. Tucson: Fireship Press.

- ^ a b c d Smith, Donald B. (1990). From the Land of Shadows: The Making of Grey Owl. Saskatoon: Western Producer Prairie Books. ISBN 0-88833-347-1.

- ^ Gleeson, Kristin (2012). "Chapter 10: The New Role of Motherhood". Anahareo: A Wilderness Spirit. Tucson: Fireship Press. ISBN 9781611792201.

- ^ Gleeson, Kristin (2012). "Chapter 11: Pursuing More Adventure". Anahareo: A Wilderness Spirit. Tucson: Fireship Press. ISBN 9781611792201.

- ^ Gleeson, Kristin (2012). "Chapter 12: A Relationship Under Strain". Anahareo: A Wilderness Spirit. Tucson: Fireship Press. ISBN 9781611792201.

- ^ "The Beaver People". National Film Board of Canada. Archived from the original on September 30, 2023. Retrieved September 20, 2023.

- ^ "Pilgrims of the Wild". National Film Board of Canada. Archived from the original on October 26, 2023. Retrieved 24 November 2023.

- ^ Gleeson, Kristin (2012). "Chapter 14: Difficult Choices". Anahareo: A Wilderness Spirit. Tucson: Fireship Press.

- ^ a b c d Gleeson, Kristin (2012). "Chapter 18: In The Public View Again". Anahareo: A Wilderness Spirit. Tucson: Fireship Press. ISBN 9781611792201.

- ^ a b c d e f Gleeson, Kristin (2012). "Chapter 16: A New Life With Old Problems". Anahareo: A Wilderness Spirit. Tucson: Fireship Press.

- ^ Gleeson, Kristin (2012). "Chapter 17: A Stubborn Vision". Anahareo: A Wilderness Spirit. Tucson: Fireship Press.

- ^ a b c d e f Gleeson, Kristin (2012). "Chapter 19: A Life Recognized". Anahareo: A Wilderness Spirit. Tucson: Fireship Press.

Further reading

[edit]- Kristin Gleeson: Anahareo: A Wilderness Spirit. Fireship Press, Tucson 2012, ISBN 1611792207.

- Kristin Gleeson: Blazing Her Own Trail: Anahareo's Rejection of Euro-Canadian Stereotypes, in Recollecting: Lives of Aboriginal Women of the Canadian Northwest and Borderlands, edited by Sarah Carter, Patricia McCormack, Athabasca University Press, 2010. The publication won the 2011 Canadian Historical Association's Aboriginal history book prize.

External links

[edit]- 1906 births

- 1986 deaths

- 20th-century Canadian non-fiction writers

- 20th-century Canadian women writers

- 20th-century First Nations writers

- Canadian animal rights activists

- Canadian autobiographers

- Canadian environmentalists

- Canadian Mohawk women writers

- Canadian Mohawk writers

- Canadian women non-fiction writers

- Members of the Order of Canada

- People from Mattawa, Ontario

- Women autobiographers

- Canadian Mohawk activists

- 20th-century indigenous women of the Americas