Batang County

Batang County

巴塘县 · འབའ་ཐང་རྫོང་། | |

|---|---|

Twin lakes in Batang, Sichuan | |

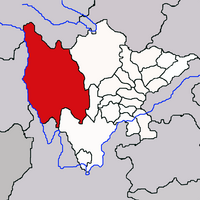

Location of Batang County (red) in the Garzê Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture (yellow) and Sichuan | |

| Coordinates (Batang County government): 30°01′12″N 99°15′00″E / 30.02000°N 99.25000°E | |

| Country | China |

| Province | Sichuan |

| Prefecture | Garzê |

| County seat | Qakyung (Batang) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 7,852 km2 (3,032 sq mi) |

| Population (2020)[1] | |

| • Total | 49,967 |

| • Density | 6.4/km2 (16/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+8 (China Standard) |

| Area code | 0836[2] |

| Website | www |

| Batang County | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 巴塘县 | ||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 巴塘縣 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Tibetan name | |||||||||||

| Tibetan | འབའ་ཐང་རྫོང་། | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Batang County (Tibetan: འབའ་ཐང་རྫོང་།; Chinese: 巴塘县) is a county located in western Garzê Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture, Sichuan Province, China. The main administrative centre is known as Batang Town (officially: Xiaqiong or Qakyung).

1990 statistics give its population as 47,256, with 42,044 living in rural areas and 5,212 living in urban areas. The nationalities mainly consist of Tibetans, Hans, and Yis, Hui, and Qiang. By far the most numerous group are the Tibetans whose population is given as 44,601. It is 260 km (160 mi) from north to south and 45 km (28 mi) west to east and has an area of 8,186 km2 (3,161 sq mi).

It borders on Xiangcheng County and Litang County in the east. Derong County to the south, Markam and Gonjo counties of Tibet and Dêqên County of Yunnan in the west, across the Jinsha or "Golden Sands" River (the upper course of the Yangtze). It borders Baiyu County to the north.[3]

It is warmer here than most of Tibet (because of the lower altitude) and is reported to be a friendly, easy-going place, surrounded by barley fields.[4][5] The plain surrounding the town is unusually fertile and produces two harvests a year. The main products include: rice, maize, barley, wheat, peas, cabbages, turnips, onions, grapes, pomegranates, peaches, apricots, water melons and honey. There are also cinnabar (mercury sulphide) mines from which mercury is extracted.[6]

The low-lying Batang Valley (altitude about 2,740 m) was one of the few regions of Tibet with a Chinese settlement before 1950. There were American Protestant and French Catholic missions here focused on medical and educational projects. "Many Bapa (natives of Batang) acquired high bureaucratic positions following the Chinese occupation in consequence of their familiarity with the Chinese language and modern education."[3]

Etymology

[edit]

The name Batang is a transliteration from Tibetan meaning a vast grassland where sheep can be heard everywhere (from ba - the sound made by the sheep + Tibetan tang which means a plain or steppe).[7][8]

History

[edit]In ancient times Qiang people lived here, and in the Han dynasty a kingdom called Bainang ('White Wolf') became established. It was an integral part of Tibet during the Tang dynasty. China made some inroads during the Yuan and Ming dynasties, and Mushi, the tribal chief of the Lijang region of Yunnan, was supported by the Ming government in his control of the region between 1568 and 1639. In 1642, Gushri Khan, the leader of the Qoshot Mongols was invited by the leaders of Tibet to aid them and he placed this whole region under his control[3] and the administration of the Dalai Lamas.

Batang was visited in the 1840s by two French priests, Abbé Évariste Régis Huc (1813–1860) and Abbé Joseph Gabet and a young Tibetan priest, who had been sent on a mission to Tibet and China by the Pope. They described it as a large, very populous and wealthy town.

It marked the furthest point of Tibetan rule on the route to Chengdu[9]

The town was completely destroyed by an earthquake in 1868 or 1869.[10] Mr. Hosie, on the other hand, dates this earthquake to 1871.[11]

The region of Batang remained under Tibetan control until 1910. Mr. Hosie, who briefly visited the region in 1904 mentions that 400 Tibetan troops were stationed to the south of the town to protect the frontier.[11]

- "In 1727, as a result of the Chinese having entered Lhasa, the boundary between China and Tibet was laid down as between the head-waters of the Mekong and Yangtze rivers, and marked by a pillar, a little to the south-west of Batang. Land to the west of this pillar was administered from Lhasa, while the Tibetan chiefs of the tribes to the east came more directly under China. This historical Sino-Tibetan boundary was used until 1910. The states Der-ge, Nyarong, Batang, Litang, and the five Hor States—to name the more important districts—are known collectively in Lhasa as Kham, an indefinite term suitable to the Tibetan Government, who are disconcertingly vague over such details as treaties and boundaries."[12] See also the account by the French Abbé Huc from the middle of the 19th century.[6]

The Abbé Auguste Desgodins, who was on a mission to Tibet from 1855 to 1870, wrote: "gold dust is found in all the rivers and even the streams of eastern Tibet". He says that in the town of Bathan or Batan, with which he was personally acquainted, there were about 20 people regularly involved in washing for gold in spite of the severe laws against it. Among other mines in this region of Tibet, Abbé Desgodins reported there were five gold mines and three silver mines being worked in the Zhongtian Province in the upper Yangtze Valley, seven mines of gold, eight of silver and several more of other metals in the upper Mekong Valley and mines of gold, silver, mercury, iron and copper in a large number of other districts. "It is no wonder than that a Chinese proverb speaks of Tibet as being at once the most elevated and the richest country in the world, and that the Mandarins are so anxious to keep Europeans out of it."[13]

The Qing government sent Feng Quan, an imperial official, to Kham to begin reasserting Qing control soon after the British invasion of Tibet under Francis Younghusband in 1904, which alarmed the Manchu Qing rulers in China, but the locals revolted and killed him.

The British invasion was one of the triggers for a Qing effort to retake Kham in 1904, when Feng Quan was sent into Tibet. His policies of land reform and reductions to the numbers of monks led to the Batang uprising which started at a Batang monastery. Christian missionaries had already withdrawn from Batang in 1887.[14][15]

The Qing government in Beijing then appointed Zhao Erfeng, the governor of Xining, "Army Commander of Tibet"[citation needed] to reintegrate Tibet into China. He was sent in 1905 (though other sources say this occurred in 1908)[16][17] on a punitive expedition and began destroying many monasteries in Kham and Amdo and implementing a process of sinification of the region:[18] The situation was soon to change, however, as, after the fall of the Qing dynasty in October 1911, Zhao's soldiers mutinied and beheaded him.[19]

In February 1910, Qing General Zhong Ying invaded Lhasa in order to directly control Tibet for the first time in Tibet's history. This invasion led to the 13th Dalai Lama's escape to India, then his return to proclaim Tibet's total independence from China in 1913, and the end of their "priest-patron" relationship.[20]

The American medical missionary, Dr Albert Shelton, lived nearly 20 years in Batang but was killed, apparently by a bandit, in 1922 on a high mountain pass near Batang at the age of 46.[21]

In 1932 the Sichuan warlord, Liu Wenhui (刘文辉; 1895–1976), drove the Tibetans back to the Yangtze River and even threatened to attack Chamdo. At Batang, Kesang Tsering, a half-Tibetan, claiming to be acting on behalf of Chiang Kai-shek (Pinyin: Jiang Jieshi. 1887–1975), managed to evict Liu Wen-hui's governor from the town with the support of some local tribes. A powerful "freebooter Lama" from the region gained support from the Tibetan forces and occupied Batang, but later had to withdraw. By August 1932 the Tibetan government had lost so much territory the Dalai Lama telegraphed the Government of India asking for diplomatic assistance. By early 1934 a ceasefire and armistices had been arranged with Liu Wen-hui and Governor Ma of Chinghai in which the Tibetans gave up all territory to the east of the Yangtze (including the region of Batang) but kept control of the Yaklo (Yenchin) district which had previously been a Chinese enclave to the west of the river.[22]

The bloodless occupation[citation needed] of Chamdo, the major city of the old Tibetan province of Kham, by the 40,000 man army of the People's Republic of China on October 19, 1950, when the whole region fell under Chinese control, served as an important precursor to the eventual defeat of the Lhasa government.[23] Chamdo's governor at the time of the occupation was Ngapoi Ngawang Jigme, who later became an official in the government of the People's Republic of China. The previous governor of Chamdo was Lhalu Tsewang Dorje.

Administrative divisions

[edit]Batang County is divided into 5 towns and 12 townships.

| Name | Simplified Chinese | Hanyu Pinyin | Tibetan | Wylie | Administrative division code | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Towns | ||||||

| Qakyung Town (Qakyung, Batang) |

夏邛镇 | Xiàqióng Zhèn | བྱ་ཁྱུང་ཀྲེན། | bya khyung kren | 513335100 | |

| Zongza Town (Zhongza) |

中咱镇 | Zhōngzá Zhèn | རྫོང་རྩ་ཀྲེན། | rdzong rtsa kren | 513335101 | |

| Cola Town (Cuola) |

措拉镇 | Cuòlā Zhèn | མཚོ་ལ་ཀྲེན། | mtsho la kren | 513335102 | |

| Gyaying Town (Jiaying) |

甲英镇 | Jiǎyīng Zhèn | རྒྱ་དབྱིང་ཀྲེན། | rgya dbying kren | 513335103 | |

| Doxong Town (Diwu) |

地巫镇 | Dìwū Zhèn | རྡོ་གཞོང་ཀྲེན། | rdo gzhong kren | 513335104 | |

| Townships | ||||||

| Lhagwa Township (Lawa) |

拉哇乡 | Lāwā Xiāng | ལྷག་བ་ཤང་། | lhag ba shang | 513335200 | |

| Chubalung Township (Zhubalong) |

竹巴龙乡 | Zhúbālóng Xiāng | གྲུ་པ་ལུང་ཤང་། | gru pa lung shang | 513335202 | |

| Suwalung Township (Suwalong) |

苏哇龙乡 | Sūwālóng Xiāng | བསུ་བ་ལུང་ཤང་། | bsu ba lung shang | 513335204 | |

| Changbo Township | 昌波乡 | Chāngbō Xiāng | འཕྲང་པོ་ཤང་། | 'phrang po shang | 513335205 | |

| Yarigang Township (Yarigong) |

亚日贡乡 | Yàrìgòng Xiāng | ཡ་རི་སྒང་ཤང་། | ya ri sgang shang | 513335208 | |

| Bokog Township (Bomi) |

波密乡 | Bōmì Xiāng | སྤོ་ཁོག་ཤང་། | spo khog shang | 513335209 | |

| Mudor Township (Moduo) |

莫多乡 | Mòduō Xiāng | མུ་གཏོར་ཤང་། | mu gtor shang | 513335210 | |

| Sumdo Township (Songduo) |

松多乡 | Sōngduō Xiāng | གསུམ་མདོ་ཤང་། | gsum mdo shang | 513335211 | |

| Bogorxi Township (Bogexi) |

波戈溪乡 | Bōgēxī Xiāng | སྤོ་སྐོར་གཤིས་ཤང་། | spo skor gshis shang | 513335212 | |

| Calu Township (Chaluo) |

茶洛乡 | Cháluò Xiāng | ཚ་ལུ་ཤང་། | tsha lu shang | 513335215 | |

| Lêyü Township (Lieyi) |

列衣乡 | Lièyī Xiāng | ལེ་ཡུལ་ཤང་། | le yul shang | 513335216 | |

| Dêda Township (Dêdar, Deda) |

德达乡 | Dédá Xiāng | སྡེ་མདའ་ཤང་། | sde mda' shang | 513335217 | |

Transport

[edit]Climate

[edit]| Climate data for Batang, elevation 2,589 m (8,494 ft), (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1981–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 26.0 (78.8) |

26.5 (79.7) |

29.7 (85.5) |

32.0 (89.6) |

34.3 (93.7) |

36.4 (97.5) |

37.9 (100.2) |

35.6 (96.1) |

35.9 (96.6) |

30.6 (87.1) |

26.5 (79.7) |

22.8 (73.0) |

37.9 (100.2) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 14.3 (57.7) |

16.9 (62.4) |

19.5 (67.1) |

22.6 (72.7) |

26.6 (79.9) |

28.9 (84.0) |

27.8 (82.0) |

27.4 (81.3) |

25.9 (78.6) |

23.1 (73.6) |

18.6 (65.5) |

14.7 (58.5) |

22.2 (71.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 4.8 (40.6) |

7.8 (46.0) |

10.9 (51.6) |

13.9 (57.0) |

17.9 (64.2) |

20.4 (68.7) |

19.9 (67.8) |

19.3 (66.7) |

17.3 (63.1) |

13.6 (56.5) |

8.4 (47.1) |

4.6 (40.3) |

13.2 (55.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −2.8 (27.0) |

0.1 (32.2) |

3.5 (38.3) |

6.8 (44.2) |

10.8 (51.4) |

14.3 (57.7) |

14.8 (58.6) |

14.4 (57.9) |

12.1 (53.8) |

6.8 (44.2) |

0.9 (33.6) |

−2.9 (26.8) |

6.6 (43.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −11.4 (11.5) |

−7.9 (17.8) |

−5.3 (22.5) |

−1.4 (29.5) |

1.2 (34.2) |

5.6 (42.1) |

7.8 (46.0) |

6.2 (43.2) |

4.2 (39.6) |

−1.7 (28.9) |

−6.6 (20.1) |

−11.6 (11.1) |

−11.6 (11.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 0.1 (0.00) |

1.4 (0.06) |

6.9 (0.27) |

19.6 (0.77) |

35.2 (1.39) |

77.9 (3.07) |

131.0 (5.16) |

114.7 (4.52) |

76.0 (2.99) |

20.9 (0.82) |

3.2 (0.13) |

0.4 (0.02) |

487.3 (19.2) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 0.2 | 1.0 | 4.1 | 8.2 | 9.9 | 15.9 | 19.6 | 18.4 | 14.1 | 6.7 | 1.8 | 0.4 | 100.3 |

| Average snowy days | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 2.6 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 28 | 27 | 33 | 40 | 43 | 53 | 65 | 66 | 65 | 52 | 39 | 32 | 45 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 219.2 | 194.4 | 193.6 | 194.8 | 221.6 | 194.9 | 181.2 | 182.7 | 181.7 | 211.7 | 210.6 | 217.3 | 2,403.7 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 67 | 61 | 52 | 50 | 52 | 46 | 43 | 45 | 50 | 60 | 67 | 69 | 55 |

| Source: China Meteorological Administration[24][25] | |||||||||||||

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ "甘孜州第七次全国人口普查公报(第二号)" (in Chinese). Government of Garzê Prefecture. 2021-06-04.

- ^ ["Batang County." "HXpedia - China's Administrative Division". Archived from the original on 2009-08-16. Retrieved 2007-12-30.]

- ^ a b c "Brief Introduction of Batang county." Archived August 16, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Mayhew, Bradley and Kohn, Michael. (2005). Tibet. 6th Edition, p. 260. Lonely Planet. ISBN 1-74059-523-8.

- ^ Buckley, Michael and Straus, Robert. (1986) Tibet: a travel survival kit, p, 219. Lonely Planet Publications. South Yarra, Victoria, Australia. ISBN 0-908086-88-1.

- ^ a b Huc, Évariste Régis (1853), Hazlitt, William (ed.), Travels in Tartary, Thibet, and China during the Years 1844–5–6, London: National Illustrated Library, pp. 122–123.

- ^ Jäschke, H. A. (1881). A Tibetan-English Dictionary. Reprint (1987): Motilal Banarsidass, Delhi, p. 228.

- ^ "Short Introduction of Batang county." Archived August 16, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Wilson, Andrew. (1875). The Abode of Snow, Reprint (1993): Moyer Bell, Rhode Island, p. 108. ISBN 1-55921-100-8.

- ^ William Mesny (1905) Mesny's Miscellany. Vol. IV, p. 397. 13 May 1905. Shanghai.

- ^ a b Hosie, A. (1905). Mr. Hosie's Journey to Tibet | 1904. First published as CD 2586. Reprint (2001): The Stationery Office, London, p. 136. ISBN 0-11-702467-8.

- ^ Chapman, F. Spencer. (1940). Lhasa: The Holy City, p. 135. Readers Union Ltd., London.

- ^ Wilson, Andrew. (1875). The Abode of Snow, Reprint (1993): Moyer Bell, Rhode Island, p. 108. ISBN 1-55921-100-8.

- ^ Bray, John (2011). "Sacred Words and Earthly Powers: Christian Missionary Engagement with Tibet". The Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan. fifth series (3). Tokyo: John Bray & The Asian Society of Japan: 93–118. Retrieved 13 July 2014.

- ^ Tuttle, Gray (2005). Tibetan Buddhists in the Making of Modern China (illustrated, reprint ed.). Columbia University Press. p. 45. ISBN 0231134460. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ^ "Ligne MacMahon." Archived 2013-06-16 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ FOSSIER Astrid, Paris, 2004 "L’Inde des britanniques à Nehru : un acteur clé du conflit sino-tibétain." [1]

- ^ "About Tibet: Later History"

- ^ Hilton, Isabel. (1999). The Search for the Panchen Lama. Viking. Reprint: Penguin Books. (2000), p. 115. ISBN 0-14-024670-3.

- ^ Tsering Shakya, "The Thirteenth Dalai Lama, Tubten Gyatso" Treasury of Lives, accessed May 11, 2021

- ^ BOOK REVIEW: "American missionary 'conquers' eastern Tibet." Pioneer in Tibet by Douglas A. Wissing. Reviewed by Julian Gearing in Asia times Online. [2]

- ^ Richardson, Hugh E. (1984). Tibet and its History. 2nd Edition, pp. 134-136. Shambhala Publications, Boston. ISBN 0-87773-376-7 (pbk).

- ^ Mayhew, Bradley and Kohn, Michael. (2005). Tibet. 6th Edition, p. 262. Lonely Planet. ISBN 1-74059-523-8.

- ^ 中国气象数据网 – WeatherBk Data (in Simplified Chinese). China Meteorological Administration. Retrieved 13 April 2023.

- ^ 中国气象数据网 (in Simplified Chinese). China Meteorological Administration. Retrieved 13 April 2023.