Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat

| "Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

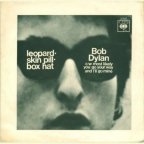

UK single, May 1967 | ||||

| Song by Bob Dylan | ||||

| from the album Blonde on Blonde | ||||

| B-side | "Most Likely You Go Your Way and I'll Go Mine" | |||

| Released | April 24, 1967 | |||

| Recorded | March 10, 1966 | |||

| Genre | Electric blues[1] | |||

| Length |

| |||

| Label | Columbia | |||

| Songwriter(s) | Bob Dylan | |||

| Producer(s) | Bob Johnston | |||

| Bob Dylan singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Audio | ||||

| "Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat" on YouTube | ||||

"Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat" is a song by the American singer-songwriter Bob Dylan, which was released on the second side of his seventh studio album Blonde on Blonde (1966). The song was written by Dylan, and produced by Bob Johnston. Dylan has denied that the song references any specific individual, although critics have speculated that it refers to Edie Sedgwick, who Dylan had spent time with in December 1965.

After several takes on January 25 and 27, 1966, in New York, the final version was finally achieved in the early hours of March 10 in Nashville. Released as a single in March 1967, "Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat" peaked at number 81 on the American Billboard Hot 100 chart in June 1967. Critics have not rated the song amongst Dylan's best, although the song's humor has been praised. From 1966 to 2013, Dylan played the song live in concert over 500 times.

Background and recording

[edit]The song was one of the first compositions attempted by Dylan and the Hawks when in January 1966 they went into Columbia recording studios in New York City to record material for Dylan's seventh studio album, which was eventually released as the double album Blonde on Blonde. Two takes of the song were attempted on January 25, and four takes on January 27, but none of the recordings were deemed satisfactory.[2][3] Frustrated with the lack of progress made with the Hawks in the New York sessions (only one song, "One of Us Must Know (Sooner or Later)", had been successfully realized), Dylan relocated to Nashville, Tennessee in February 1966, following the recommendation of his producer Bob Johnston.[4] Johnston hired experienced session musicians, who were joined by Robbie Robertson of the Hawks, and Al Kooper, who had both played at the New York sessions.[5]

Dylan completed the lyrics for the song between the New York and Nashville sessions.[6] In Nashville, the evening of the first day of recording, February 14, was devoted to "Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat". Present at the session were Charlie McCoy (guitar and bass), Kenny Buttrey (drums), Wayne Moss (guitar), Joe South (guitar and bass), Kooper (organ), Hargus Robbins (piano) and Jerry Kennedy (guitar). Earlier in the day Dylan and the band had achieved satisfactory takes of "Fourth Time Around" and "Visions of Johanna" (which were included on the album), but none of the 13 takes of "Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat" recorded on February 14 were to Dylan's satisfaction. Dylan soon left Nashville to play some concerts with the Hawks. He returned in March for a second set of sessions. A satisfactory take of "Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat" was finally achieved in the early hours of March 10, 1966.[2] Dylan sang on the track, and played electric guitar and harmonica.[7] Kennedy was absent, but, in addition to the musicians from the earlier session, Henry Strzelecki was on bass, and Robertson was on lead guitar, though Dylan himself plays lead guitar on the song's opening 12 bars.[2]

Releases

[edit]Blonde on Blonde, Dylan's seventh studio album, was issued as a double album on June 20, with "Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat" as the third track on side two.[8][9] The album version had a duration of three minutes and fifty-eight seconds.[1]

The song was included on an EP in West Germany in late 1966.[10] On April 24, 1967, an edited version lasting 2 minutes and 20 seconds was issued as a single in the United States, Canada, and the Netherlands.[10][a] The Netherland release had a different duration, fading out at 3:42.[10] A UK release of the 2:20 version followed, on May 5, with an Italian release the following month.[10] The single was also released, either in 1967 or around 1967, in Australia, Denmark, France, Greece, New Zealand, Norway, Portugal, South Africa, and West Germany.[10] The singles had "Most Likely You Go Your Way and I'll Go Mine" as the B-side.[10][12] The single reached number 81 on the Billboard Hot 100, and 97th place on the Cashbox chart.[13][14]

The first take from January 25 was released on The Bootleg Series Vol. 7: No Direction Home: The Soundtrack (2005).[15] The recording sessions were released in their entirety on the 18-disc Collector's Edition of The Bootleg Series Vol. 12: The Cutting Edge 1965–1966 (2015) with highlights from the February 14, 1966, outtakes appearing on the 6-disc and 2-disc versions of that album.[16]

Composition and lyrical interpretation

[edit]Fashion victim

[edit]Dylan's lyrics affectionately ridicule a female "fashion victim" who wears a leopard-skin pillbox hat. The pillbox hat was a fashionable ladies' hat in the United States in the early to mid-1960s, most famously worn by Jacqueline Kennedy.[17][18] Dylan satirically crosses this accessory's high-fashion image with leopard-skin material, perceived as more downmarket and vulgar. The song was also written and released after pillbox hats had been at the height of fashion.[17]

The narrator of the song is addressing a woman that he wants to be with.[19] In one verse, the narrator has been advised by the doctor not to see the woman, then finds her with the doctor at his office: "You know, I don't mind him cheatin' on me / But I sure wish he'd take that off his head / Your brand new leopard-skin pill-box hat".[19][20] In the last verse, the narrator says that he is aware that the woman has a new partner: "I saw him makin' love to you / you forgot to close the garage door".[19][20]

Possible allusion to Edie Sedgwick

[edit]Some journalists and Dylan biographers have speculated that the song was inspired by Edie Sedgwick, an actress and model associated with Andy Warhol.[2][21] Dylan had spent time with Sedgwick in December 1965,[22] and according to Sedgwick's former housemate Danny Fields, Sedgwick owned a leopard-skin hat.[23][24] Dylan's biographer Clinton Heylin wrote that, "for a brief moment, Dylan seemed fascinated by this ill-fated starlet".[22][22] Scholar of English Graley Herren wrote in 2018 that "most Dylanologists consider Sedgwick the subject of jealous mockery" in the song.[25] It has been suggested that Sedgwick was an inspiration for other Dylan songs of the time as well, particularly some from Blonde on Blonde;[26][25] Heylin thought that "One of Us Must Know (Sooner or Later)" was an example.[22]

Asked in a 1969 interview with Jann Wenner what the song was about, Dylan replied:[27]

It's just about that. I think that's something I mighta taken out of the newspaper. Mighta seen a picture of one in a department store window. There's really no more to it than that ... Just a leopard skin pillbox. That's all.

When asked by his biographer Anthony Scaduto whether songs on Blonde on Blonde such as "Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat" referred to specific people, Dylan said that the numbers were "coming down hard on all the people, not just specific people".[28] another of Dylan's biographers, Robert Shelton interpreted the song as "A sustained joke about mindless excess", where "the hat could mean any trend in fashion or speech, popular or high culture".[29]

Influences

[edit]"Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat" is a 12-bar blues,;[30] melodically and lyrically it resembles Lightnin' Hopkins's "Automobile Blues",[19][31] English language scholar Douglas Mark Ponton wrote that although Dylan has sometimes uses Delta blues themes such as love, sex, mourning and anxiety when composing original blues songs, "he also brings his own kind of lyrical inventiveness to the form, taking it into new semantic territory."[32] Ponton takes "Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat" as an example, where Dylan takes a piece of clothing that is outside the traditional blues lexicon into his song, rather than using the metaphor of an automobile for a woman that had been used by Robert Johnson and Hopkins.[33] Another possible influence, identified by Craig McGregor in The Sydney Morning Herald, is "In the Evenin'".[34][b]

| "Automobile Blues" (1961) | "Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat" (Take 1) |

|---|---|

|

I saw you riding' 'round in your brand-new automobile |

Well, I see you got your brand-new leopard-skin pill-box hat |

Critical reception

[edit]McGregor rated the "very funny" song as one of the best on Blonde on Blonde.[34] When the single was released, a Billboard reviewer considered that both sides were "powerful off-beat" numbers with "strong dance beats and compelling Dylan lyrics loaded with teen sales appeal".[37] A staff writer for Cash Box described "Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat" as a "raunchy blues-type item" that Dylan's fans would find agreeable.[38]

Musicologist Wilfrid Mellers described the music as "a frisky boogie rhythm, with plangent blue notes so rapid that they sound more like chortles than sighs".[39] He felt that Dylan "defuses negative emotions with humour" in the song.[39] Conversely, music critic Paul Williams felt that it was "the only really mean-spirited song on the album".[40] "Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat" was dismissed as a "minor song" by Michael Gray, who thought that it was merely a "good joke and a vehicle for showing Dylan's electric lead guitar-work".[41] However, Gray did acclaim Dylan's delivery of "You know it balances on your head / Just like a mattress balances / On a bottle of wine", arguing that "it would be hard to find a better instance of words, tune and delivery working so entirely together".[41] Author John Nogowski rated the song as "B+", and described it as a "standard blues, with some funny lyrics".[42] He noted that the track is the only one that credits a guitar solo to Dylan, but felt "He's no Eric Clapton, but it's fun, nevertheless."[42] Neil Spencer gave the song a rating of 4/5 stars in an Uncut magazine Dylan supplement in 2015.[43]

A 2015 Rolling Stone listing of Dylan's best songs included "Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat" in 67th position, referring to it as "a little masterpiece of inside-out innuendo and twisted double-entendre".[44] The same year, USA Today ranked 359 of Dylan's songs, placing the track at number 200.[45] Jim Beviglia had rated it 166th amongst Dylan's songs in his 2013 book.[46]

Live performances

[edit]According to his website, Dylan played "Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat" 535 times in concert from 1966 to 2013.[20] The site lists the earliest live performance as February 26, 1966, but the first known live performance was on February 5.[20][47] A live version from May 17, 1966, was included on The Bootleg Series Vol. 4: Bob Dylan Live 1966, The "Royal Albert Hall" Concert (1998).[48] On July 7, 1984, Dylan performed the song with Clapton and Chrissie Hynde at Wembley Stadium as part of his tour with Santana.[49] The next day, at Slane Castle, Dylan was due to duet with Bono on the track, but Bono forgot the lyrics and left the stage.[49][50][c]

Usage by other artists

[edit]Cat Power has covered the song as part of her Cat Power Sings Dylan show, including a performance at the Royal Albert Hall in November 2022 in which she recreated the "Royal Albert Hall" concert.[51]

In 2013, experimental hip-hop band Death Grips released a song entitled "You Might Think He Loves You for Your Money but I Know What He Really Loves You for It’s Your Brand New Leopard Skin Pillbox Hat". The song takes its title from a lyric in "Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat", although no reference to Dylan's song itself is made within their song.[52]

Personnel

[edit]

The personnel for the album version were as follows.

Musicians[7]

- Bob Dylan – vocals, electric guitar

- Charlie McCoy – acoustic guitar

- Robbie Robertson – electric guitar

- Wayne Moss – electric guitar

- Joe South – electric guitar

- Al Kooper – organ

- Hargus Robbins – piano

- Henry Strzelecki – electric bass

- Kenneth Buttrey – drums

Technical[54]

- Bob Johnston – production

Charts

[edit]| Chart (1967) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| US Billboard Hot 100[55] | 81 |

| US Top 100 (Cashbox)[14] | 97 |

Notes

[edit]- ^ Some sources, e.g. Williams (2004) and Nogowski (2022), date the release to March 1967.[11][12]

- ^ Dylan played Leroy Carr's "In the Evening (When the Sun Goes Down)" (1935) at Bonnie Beecher's house in 1961, a performance that later circulated on bootleg recordings.[35]

- ^ Bono rejoined Dylan for the next song in the set, Dylan's "Blowin' in the Wind", and sang his own version of the lyrics for two verses; Dylan followed the first of these with his own lyrics. Jack Whatley of Far Out described it as a "car crash duet".[50]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Margotin & Guesdon 2022, pp. 226–227.

- ^ a b c d Heylin 2009, pp. 287–290.

- ^ Williams 2004, p. 284.

- ^ Heylin 2021, pp. 388–389.

- ^ Wilentz 2010.

- ^ Sanders 2020, p. 135.

- ^ a b Sanders 2020, p. 278.

- ^ Nogowski 2022, p. 59.

- ^ Heylin 2016, 7290: a Sony database of album release dates ... confirms once and for all that it came out on June 20, 1966"..

- ^ a b c d e f Fraser, Alan. "Audio: 1966–67 – Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat". Searching for a Gem. Archived from the original on March 25, 2023. Retrieved May 29, 2023.

- ^ Williams 2004, p. 289.

- ^ a b Nogowski 2022, p. 57.

- ^ "Chart history: Bob Dylan". Billboard. Archived from the original on January 23, 2023. Retrieved January 23, 2023.

- ^ a b Downey, Albert & Hoffman 1994, p. 105.

- ^ Nogowski 2022, p. 276.

- ^ "Bob Dylan – The Cutting Edge 1965–1966: The Bootleg Series Vol. 12". Bob Dylan's official website. Archived from the original on February 7, 2016. Retrieved November 29, 2015.

- ^ a b Chico 2013, pp. 378–379.

- ^ Gill 2013, pp. 144–145.

- ^ a b c d Marqusee 2005, p. 191.

- ^ a b c d "Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat". Bob Dylan's official website. Archived from the original on March 4, 2023. Retrieved March 4, 2023.

- ^ Hamilton 2010, p. 289.

- ^ a b c d Heylin 2021, p. 386.

- ^ Seabrook, John (August 30, 2010). "The Back Room". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on March 2, 2014. Retrieved May 31, 2023.

- ^ Finkelstein & Dalton 2006, p. 119.

- ^ a b Herren 2018, p. 15.

- ^ Cresap 2004, p. 183.

- ^ Wenner, Jann (November 29, 1969). "Bob Dylan: The Rolling Stone Interview". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on February 27, 2023. Retrieved May 28, 2023.

- ^ Scaduto 1971, p. 244.

- ^ Shelton 1987, p. 323.

- ^ Gill 2013, p. 144.

- ^ Trager 2004, pp. 368–369.

- ^ Ponton 2020, p. 181.

- ^ Ponton 2020, pp. 181–182.

- ^ a b McGregor, Craig (October 8, 1966). "Pop scene". The Sydney Morning Herald. p. 19.

- ^ Barker 2008, pp. 168–169.

- ^ Sanders 2020, p. 80–81.

- ^ "Spotlight Singles". Billboard. May 6, 1967. p. 20.

- ^ "Record reviews". Cash Box. May 6, 1967. p. 24.

- ^ a b Mellers 1985, p. 147.

- ^ Williams 2004, p. 195.

- ^ a b Gray 2004, p. 150.

- ^ a b Nogowski 2022, p. 61.

- ^ Spencer, Neil (2015). "Blonde on Blonde". Uncut – Ultimate Music Guide: Bob Dylan. p. 25.

- ^ "100 Greatest Bob Dylan Songs. 67: "Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat" (1966)". Rolling Stone. July 3, 2020 [2015]. Archived from the original on January 28, 2023. Retrieved May 29, 2023.

- ^ Chase, Chris (May 24, 2021) [2015]. "Ranking all of Bob Dylan's songs, from No. 1 to No. 359". USA Today. Archived from the original on May 24, 2021. Retrieved May 29, 2015.

- ^ Beviglia 2013, p. 189.

- ^ Heylin 2009, p. 287.

- ^ Unterberger, Richie. "The Bootleg Series, Vol. 4: The "Royal Albert Hall" Concert". AllMusic. Archived from the original on March 4, 2023. Retrieved March 4, 2023.

- ^ a b Björner, Olof (January 31, 2022). "Still on the Road: 1984 Europe tour". Archived from the original on March 23, 2023. Retrieved May 30, 2023.

- ^ a b Whatley, Jack (September 4, 2020). "Revisit Bob Dylan and Bono's car crash duet of 'Blowin' in the Wind' in 1984". Far Out. Archived from the original on July 13, 2022. Retrieved May 30, 2023.

- ^ Minsker, Evan (September 12, 2023). "Cat Power Releasing Live Album Cat Power Sings Dylan: The 1966 Royal Albert Hall Concert". Pitchfork. Pitchfork Media.

- ^ Lloyd, Kate (December 13, 2013). "Death Grips – 'Government Plates'". NME. BandLab Technologies.

- ^ Robertson 2016, p. 214.

- ^ Sanders 2020, p. 276.

- ^ Whitburn 2013, p. 262.

Sources

- Barker, Derek (2008). The Songs He Didn't Write: Bob Dylan Under The Influence. Chrome Dreams. ISBN 978-1-84240-424-9.

- Beviglia, Jim (2013). Counting Down Bob Dylan: His 100 Finest Songs. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-8824-1.

- Chico, Beverly (2013). Hats and Headwear around the World: A Cultural Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 378–379. ISBN 978-1-61069-063-8.

- Cresap, Kelly M. (2004). Pop Trickster Fool: Warhol Performs Naivete. University of Illinois Press. p. 183. ISBN 978-0-252-07181-2.

- Downey, Pat; Albert, George; Hoffman, Frank (1994). Cash Box pop singles charts, 1950–1993. Libraries Unlimited. p. 105. ISBN 978-1-56308-316-7.

- Finkelstein, Nat; Dalton, David (2006). Edie, factory girl. VH1 Press. ISBN 978-1-57687-346-5.

- Gill, Andy (2013). Bob Dylan: The Stories Behind the Songs 1962-1969. Carlton Books. pp. 144–145. ISBN 978-1-84732-759-8.

- Gray, Michael (2004). Song and Dance Man III: The Art of Bob Dylan. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8264-6382-1.

- Hamilton, Ed (2010). Legends of the Chelsea Hotel: Living with the Artists and Outlaws in New York's Rebel Mecca. Da Capo Press. p. 289. ISBN 978-0-306-82000-7.

- Herren, Graley (2018). "Mythic Quest in Bob Dylan's Blonde on Blonde". Rock Music Studies. 5 (2): 124–141. doi:10.1080/19401159.2018.1446246. S2CID 194995653.

- Heylin, Clinton (2009). Revolution in the Air: The Songs of Bob Dylan, 1957-1973. Chicago Review Press. ISBN 978-1-56976-268-4.

- Heylin, Clinton (2016). Judas!: From Forest Hills to the Free Trade Hall: A Historical View of Dylan's Big Boo (Kindle ed.). Route Publishing. ISBN 978-1-901927-68-9.

- Heylin, Clinton (2021). The Double Life of Bob Dylan. Vol. 1 1941-1966, A restless, hungry feeling. The Bodley Head. ISBN 978-1-84792-588-6.

- Margotin, Philippe; Guesdon, Jean-Michel (2022). Bob Dylan All the Songs: The Story Behind Every Track (Expanded ed.). Black Dog & Leventhal. ISBN 978-0-7624-7573-5.

- Marqusee, Mike (2005). Wicked Messenger: Bob Dylan and the 1960s. Seven Stories Press. ISBN 978-1-58322-686-5.

- Mellers, Wilfrid (1985). A Darker Shade of Pale: A Backdrop to Bob Dylan. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-571-13345-1.

- Nogowski, John (2022). Bob Dylan: A Descriptive, Critical Discography and Filmography, 1961-2022 (3rd ed.). McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-1-4766-4362-5.

- Ponton, Douglas Mark (2020). "14. Black and White Blues: the sounds of Delta Blues singing". In Ponton, Douglas Mark; Zagratzki, Uwe (eds.). Blues in the 21st Century: Myth, Self-Expression and Trans-Culturalism. Wilmington: Vernon Press. pp. 177–192. ISBN 978-1-62273-634-8.

- Robertson, Robbie (2016). Testimony. Crown Archetype. ISBN 978-0-307-88980-5.

- Sanders, Daryl (2020). That Thin, Wild Mercury Sound: Dylan, Nashville, and the Making of Blonde on Blonde (epub ed.). Chicago Review Press. ISBN 978-1-61373-550-3.

- Scaduto, Anthony (1971). Bob Dylan. Grosset & Dunlap. ISBN 978-0-448-02034-1.

- Shelton, Robert (1987). No Direction Home: the Life and Music of Bob Dylan. New English Library. ISBN 978-0-450-04843-2.

- Trager, Oliver (2004). Keys to the Rain: the Definitive Bob Dylan Encyclopedia. Billboard Books. ISBN 978-0-8230-7974-2.

- Whitburn, Joel (2013). Joel Whitburn's Top Pop Singles 1955–2012 (14th ed.). Record Research. p. 262. ISBN 978-0-89820-205-2.

- Wilentz, Sean (2010). "4: The Sound of 3:00 am: The Making of Blonde on Blonde, New York City and Nashville, October 5, 1965 – March 10 (?), 1966". Bob Dylan in America. Vintage Digital. ISBN 978-1-4070-7411-5. Archived from the original on August 19, 2022. Retrieved August 21, 2022 – via Pop Matters.

- Williams, Paul (2004) [1990]. Bob Dylan, Performing Artist: The Early Years, 1960–1973. Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-1-84449-095-0.

External links

[edit]- Lyrics, from Bob Dylan's official website