Nevillean theory of Shakespeare authorship

The Nevillean theory of Shakespeare authorship contends that the English parliamentarian and diplomat Henry Neville (1564–1615) wrote the plays and poems traditionally attributed to William Shakespeare.

First proposed in 2005, the theory relies upon perceived correspondences between aspects of Neville's life and the circumstances surrounding and contents of Shakespeare's works, interpretative readings of manuscripts purportedly connected with Neville, cryptographic ciphers and codes in the dedication to Shakespeare's Sonnets, and other perceived links between Neville and Shakespeare’s works. In addition, a conspiracy is posited in which Ben Jonson attributed the First Folio to William Shakespeare to hide Neville’s authorship.

For authorial attribution of unknown authors, academics rely on title pages, testimony by contemporary poets and historians, and official records. There is no convergence of documentary evidence supporting the candidacy of Sir Henry Neville as a ‘hidden’ author. The majority of Shakespeare scholars and literary historians accept that the convergence of documentary evidence supporting Shakespeare is sufficient to establish his authorship. They reject all alternative authorship candidates, including Neville. Indeed, Carroll asserts “... antagonism to the authorship debate from within the profession is so great that it would be difficult for a professed Oxfordian to be hired in the first place, much less gain tenure...".[1] Despite this hostility, in a 2007 New York Times survey of 265 Shakespeare professors, 6% said “Yes” there is good reason to question Shakespeare's authorship, and a further 11% said “Possibly”.[2] The few who have responded to claims for Neville have overwhelmingly dismissed the theory. They say the theory has no credible evidence, relies upon factual errors and distortions, and ignores contrary evidence.

Description

[edit]The basis of the Nevillean theory is that William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon was not the real author of the works traditionally attributed to him, but instead a front to conceal the true author, Henry Neville.[3] In their attempt to establish this, author Brenda James, historian William Rubinstein and author John Casson cite many of the same arguments proposed by other anti-Stratfodian theories. The theory suggests that these four main elements, when taken together, reveal that Neville was the hidden author behind the works:

- Biographical details, including his lifespan in relation to Shakespeare, access to known sources of Shakespeare's works, affiliation with people connected to the works of Shakesepare, and biographical coincidences with events described in Shakespeare’s plays and poems

- A conspiracy in which Ben Jonson was complicit in hiding Neville's identity as the true author

- An interpretative reading of the Northumberland Manuscript and a manuscript known as the Tower Notebook

- A cipher message hidden in the dedication of Shakespeare's Sonnets

Arguments from biography

[edit]The theory proposes that many aspects of Neville's biography may be seen as relevant, most fundamentally that Neville's birth and death dates (1562–1615) are similar to Shakespeare's (1564–1616).[4][5]

Shakespeare's poems Venus and Adonis (1593) and The Rape of Lucrece (1594) bear dedications to Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton signed by "William Shakespeare". James and Rubinstein assert that there is "no evidence" Southampton was Shakespeare's patron, that the dedication was written by Neville as a "joke", and that Southampton and Neville were friends in the 1590s. Kathman writes that the existence of the dedication is itself evidence of Southampton's patronage of Shakespeare, that James and Rubinstein "dismiss" Neville's explicit 1601 testimony that he had not spoken to Southampton between his childhood and the abortive 1601 Essex Rebellion, and that Neville and Southampton's friendship is only documented from 1603 onward.[1]

James and Rubinstein argue that "Neville's experiences, such as travel on the Continent and imprisonment in the Tower, correspond with uncanny exactness to the materials of the plays and their order."[6] They suggest that the Essex rebellion "explains the move towards darker comedies and tragedies in Shakespeare’s writing".[7]

James and Rubinstein advance their argument by what MacDonald P. Jackson calls "tracing improbable connections between Shakespeare's works and Neville's busy public life". For instance, they suggest that the French language dialogue in Henry V, written in 1599, coincides with Neville's experience as ambassador to France (1599-1601). They also propose that the use of certain Italian words in the plays shows that their author must have been in Italy, as Neville was. Jackson writes that Shakespeare could have derived the dialogue in Henry V from a phrasebook and could have learned about Italy from guidebooks and from Italians in London.[2]

Conspiracy

[edit]

As with many other anti-Stratfordian theories, the Nevillean theory holds that Ben Jonson conspired to conceal the true author of Shakespeare's works.[9] James and Rubinstein assert that a conspiracy "must have occurred" and that John Heminges and Henry Condell, who helped prepare the first printed edition of Shakespeare's plays, were in on it.[10]

James and Rubinstein also cite the famous phrase "Sweet Swan of Avon" Jonson uses in his poem prefacing the First Folio. They suggest that since "native swans in Britain are mute" this is a subtle hint from Jonson that Shakespeare was not a "true writer".[11] As motive for the conspiracy, the Nevilleans argue that a man with Neville's aristocratic status would not want to have been known as a playwright.[12]

MacDonald P. Jackson writes that since there are also two dozen contemporaneous written accounts of Shakespeare as a playwright, for the conspiracy to be real all these accounts must be the work of "liars or dupes".[13] Matt Kubus[who?] writes that for the conspiracy to work, all of Shakespeare's many known collaborators would have had to have known he was a front man, and kept silent. Kubus says this is hard to believe.[14]

Arguments from documentary evidence

[edit]In addition to the circumstances of Neville's life, the theory adduces several pieces of documentary evidence.

Chief among these is the so-called "Tower Notebook", a 196-page manuscript of 1602 that details royal protocols, and which James and Rubinstein assert is "unquestionably" the work of Neville, despite it not bearing Neville's name or containing any text in his handwriting. One page of the notebook contains descriptions of protocols for the coronation of Anne Boleyn which are similar to stage directions in Henry VIII, a play Shakespeare co-wrote with John Fletcher. The scholarly consensus is that the scene in question was written by Fletcher.[15]

A further argument is based on handwritten annotations in a 1550 edition of the book Union of the Two Noble and Illustre Families of Lancashire and York by Edward Hall. The annotations had previously been speculated to be in Shakespeare's hand, and been the subject of some academic debate since the 1950s. Because another book with the same library mark bore the name "Worsley", and because "Worsley" is a name within the Neville family, James and Rubinstein assert that the handwritten annotations must be Neville's.[16]

Another document produced in evidence is the front cover of the Northumberland Manuscript. This tattered piece of paper contains many words and handwritten names of figures of the age, including Shakespeare's, Francis Bacon's, and "the word 'Nevill' followed by the punning Latin family motto 'ne vile velis' (desire nothing base)". Although there is no evidence Neville had any involvement with the document, James and Rubinstein argue that he is its author, and that it is evidence he "practised Shakespeare's signature." The page has also been used by Baconians as supposed evidence for Bacon being the true author of Shakespeare's works.[17]

John Casson, author of the 2016 book Sir Henry Neville Was Shakespeare: The Evidence, also argues for the Neville theory. Casson discovered in the British Library an annotated copy of François de Belleforest’s Histoires Tragiques (1576), a French translation considered a possible source of Hamlet.[18] Casson believes it likely the annotations are Shakespeare's, and that they strengthen the case for Neville being Shakespeare, since Neville knew French and books at Audley End contain handwriting which has a letterform which appears similar.[19]

Casson also compared Henry Neville's letters with the works of Shakespeare, noting correspondences with words that occur only once in the works of Shakespeare.[20] In addition, Casson found handwritten annotations in Neville's library; they appear to match the types of research that would have been necessary to write the works of Shakespeare.[21]

Code theory

[edit]

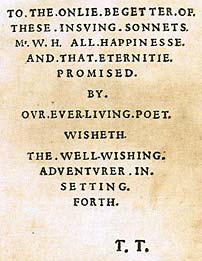

In 1964, Leslie Hotson first suggested that the strange Dedication to Shakespeare's Sonnets may be a code.[22] In 1997 John Rollet discovered the word “HENRY” in a 15-column setting of the Dedication to Shakespeare's Sonnets (1609).[23] Rollet surmised that this might refer to Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton. In 2005, using the same setting, Brenda James assembled additional fragments which first led her to identify and to research the biography of Sir Henry Neville,[24] a name previously unknown to her. Following this investigation, she concluded that Neville was the true author of the works attributed to William Shakespeare.[24]

Advance publicity for James' and Rubinstein's book promised it would contain revelations about how Neville's name was encoded by cipher in the dedication to Shakespeare's sonnets, but by the time of the publication of the American edition in 2007 this has been downplayed and appears only in a footnote.[25] Nevertheless in a 2008 monograph entitled Henry Neville and the Shakespeare Code, Brenda James sets out how she "decoded" the dedication to the sonnet to reveal Neville's name. The process begins with laying the 144 letters of the dedication on a 12 by 12 grid and proceeds through 18 pages of explanation. Matt Kubus, has challenged James's code theory, suggesting that it undermined the other arguments in The Truth Will Out, commenting that "It is difficult to relate James's argument without appearing derisive", and that it is "peppered with assumptions".[26]

James and Rubinstein did not publish their code theory in The Truth Will Out. In 2006, without knowledge of the details of James's work, Leyland and Goding set out to decrypt the dedication text independently, as a blind test of James's work. When James's cryptographic work was finally published in Henry Neville and the Shakespeare Code (2008), Leyland and Goding found that they had used a similar 15-column setting of the dedication to the sonnets but that they had included hyphens from the original text that were not included either by Rollet or James. In addition, they argue that there are many instances where the grid co-ordinates of a key letter in the dedication may be paired with the number of a sonnet, such that the sonnet illuminates the encrypted text (and vice versa). They also claim that the Dedication code is similar to the distinctive diplomatic codes used by Neville himself since both rely on grids of paired letters and numbers.[27]

Related Research

[edit]Casson argues in his 2009 book Enter Pursued by a Bear that Neville wrote the Phaeton sonnet in a book by John Florio, and that Neville-as-Shakespeare also contributed to several plays in the Shakespeare apocrypha.[28] English literature professor Brean Hammond writes that in Bear, Casson "argues that Double Falsehood is indeed the lost Cardenio -- that Shakespeare's hand is certainly in it". Casson uses an idea proposed by Ted Hughes for identifying telltale patterns of imagery that modulate throughout Shakespeare's oeuvre. Hammond finds the approach "not convincing". Hammond writes that Casson's claims of telling connections between Neville, Fletcher, and Spain suffer from "a degree of" fluellenism – the imparting of non-existent significance to mere coincidences. However, Hammond suggests that Casson provides valuable material that warrants further study.[29]

There was a dedicated Journal of Neville Studies.[30]

History and Reception

[edit]The theory of Nevillean authorship was first proposed by Brenda James who had drafted an entire book before meeting her eventual co-author, historian William D. Rubinstein. Their book was published in 2005 entitled The Truth Will Out: Unmasking the Real Shakespeare.[31]

At the time of the launch of The Truth Will Out Jonathan Bate said there was "not the slightest shred of evidence" to support its contentions.[32] MacDonald P. Jackson wrote in a book review of The Truth Will Out that "it would take a book to explain all that is wrong".[33] Reviewing the 2007 American edition of The Truth Will Out in the Shakespeare Quarterly, David Kathman wrote that despite its bold claims, "the promised 'evidence' is non-existent or very flimsy," and that the book is "a train wreck" filled with "factual errors, distortions, and arguments that are incoherent" as well as "pseudoscholarly inanities".[34]

Robert Pringle rejected Neville's authorship, explaining that "Shakespeare received a thoroughly good classical education at the Stratford grammar school and then, for well over 20 years, was involved in artistic and intellectual circles in London."[35] Brian Vickers also rejected the Neville theory, similarly arguing that "Elizabethan grammar school was an intense crash course in reading and writing Latin verse, prose, and plays – the bigger schools often acted plays by Terence in the original."[36]

In answer to the negative reception the book received, editions following the first English one carry an afterword from Brenda James complaining about what she describes as a lack of "informed academic response".[37]

According to Stanley Wells in his book What Was Shakespeare Really Like?, Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh supported the candidacy of Henry Neville for the authorship of the works of Shakespeare.[38]

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Carroll, D. Allen (2004). "Reading the 1592 Groatsworth Attack on Shakespeare". Tennessee Law Review. 72 (1): 277–94.

- ^ a b Niederkorn, William S. (22 April 2007). "Shakespeare Reaffirmed". The New York Times. Retrieved 20 December 2010.

- ^ Kathman 2007, p 245.

- ^ Alberge 2005.

- ^ Casson, Rubinstein & Ewald (2010), p. 114.

- ^ Craig 2012, p 16-7.

- ^ Maguire 2012, p. 199

- ^ Walsh 2006, p. 125.

- ^ Walsh 2006, p. 125.

- ^ Kathman 2007, p. 246; Jackson, p. 40.

- ^ Kubus 2013, p. 69.

- ^ Casson, Rubinstein & Ewald (2010), p. 130.

- ^ Jackson 2005, p. 40

- ^ Kubus 2013, p. 68.

- ^ Kathman 2007, pp. 246-247.

- ^ Kathman 2007, p. 247.

- ^ Jackson 2005, p. 39; Kathman 2007, p. 247.

- ^ Flood 2018; The Telegraph 2009.

- ^ Flood 2018.

- ^ Ostrowski, p. 150

- ^ Lebens, p. 210

- ^ Hotson, Leslie (1964). Mr WH. London: Rupert Hart-Davis.

- ^ Rollet, J. M. (1999). "Secrets of the Dedication to Shakespeare's Sonnets". The Oxfordian. 5 (2): 60–75.

- ^ a b James, B & Rubinstein, W (2005). The Truth Will Out: Unmasking the Real Shakespeare. Harlow, UK: Pearson Longman. ISBN 9780061847448.

- ^ Kathman, David (2007). "The Truth Will Out: Unmasking the Real Shakespeare". Shakespeare Quarterly (Book Review). 58 (2): 245–248. doi:10.1353/shq.2007.0024. S2CID 191612971.

- ^ Kubus, Matt (2013). "The unusual suspects". In Paul Edmonson; Stanley Wells (eds.). Shakespeare Beyond Doubt. Cambridge University Press. pp. 54–56. ISBN 9781107354937.

- ^ Leyland, James; Goding, James (2018). Who Will Believe my Verse? The Code in Shakespeare's Sonnets. Melbourne: Australian Scholarly Publishing. ISBN 978-1925588675.

- ^ The Telegraph 2009; Hammond 2012, pp. 67-68.

- ^ Hammond 2012, pp. 67-68.

- ^ Hammond 2012, pp. 67-68.

- ^ Kathman 2007, p 245.

- ^ BBC News 2005.

- ^ Jackson 2005, p. 39.

- ^ Kathman 2007, pp. 245, 248.

- ^ Wiant 2005

- ^ Flood 2018

- ^ Walsh 2006, p. 125; Hammond 2012, pp. 67-68.

- ^ Wells 2023, p.135

References

[edit]- Alberge, Dalya (5 October 2005). "Now Falstaff gets the role of man who wrote Shakespeare". The Times. Retrieved 3 January 2020.

- BBC News (5 October 2005). "Diplomat 'was real Shakespeare'".

- Casson, John; Rubinstein, William D. & Ewald, David (2010). "Chapter 5: Our Shakespeare: Henry Neville 1562–1615". In Leahy, William (ed.). Shakespeare and His Authors: Critical Perspectives on the Authorship. Continuum. pp. 113-138. ISBN 978-1-4411-4836-0.

- Craig, Hugh (2012). "Chapter 1: Authorship". In Kinney, Arthur (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Shakespeare. Oxford University Press. pp. 16–17. ISBN 9780199566105.

- Flood, Alison (5 March 2018). "Shakespeare himself may have annotated 'Hamlet' book, claims researcher". The Guardian. Retrieved December 26, 2019.

- Gore-Langton, Robert (29 December 2014). "The Campaign to Prove Shakespeare Didn't Exist". Newsweek. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- Hammond, Brean (2012). "Chapter 3: After Arden". In Carnegie, David; Taylor, David (eds.). The Quest for Cardenio: Shakespeare, Fletcher, Cervantes, and the Lost Play. Oxford University Press. p. 67-8. ISBN 9780199641819.

- Jackson, MacDonald P. (2005). "Stunning the literary world: Shakespeare as Stooge". Shakespeare Newsletter (Book Review). 55 (2): 35.

- James, B. & Rubinstein, W. (2005). The Truth Will Out: Unmasking the Real Shakespeare. Harlow, UK: Pearson Longman. ISBN 9780061847448.

- Kathman, David (2007). "The Truth Will Out: Unmasking the Real Shakespeare". Shakespeare Quarterly (Book Review). 58 (2): 245–248. doi:10.1353/shq.2007.0024. S2CID 191612971.

- Kubus, Matt (2013). "The unusual suspects". In Paul Edmonson; Stanley Wells (eds.). Shakespeare Beyond Doubt. Cambridge University Press. pp. 54–56. ISBN 9781107354937.

- Lebens, Samuel (2020). The Principles of Judaism. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198843252.

- Leyland, J.B. & Goding, J.W. (2018). Who will believe my verse? The code in Shakespeare's Sonnets. Melbourne: Australian Scholarly. ISBN 9781925588675.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Maguire, Laurie; Smith, Emma (2012). 30 Great Myths about Shakespeare. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781118326770.

- Ostrowski, Donald (2020). Who Wrote That? Authorship Controversies from Moses to Sholokhov. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press. ISBN 9781501749728.

- The Telegraph (17 March 2009). "Academic 'discovers' six works by William Shakespeare". Retrieved December 27, 2019.

- Walsh, William D. (2006). "Art & Humanities". Library Journal (Book Reviews). 131 (20).

- Wells, Stanley (2023). What Was Shakespeare Really Like?. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 1009340379.

- Wiant, Jenn (19 October 2005). "Bard Bashing In Vogue". Associated Press. Retrieved 30 December 2019.