Conference Presentations by Eric Nemarich

Panel Abstract, Speakers' Biographies, and Individual Paper Abstracts

From at least the twelfth ... more Panel Abstract, Speakers' Biographies, and Individual Paper Abstracts

From at least the twelfth century notaries were central to the administration of the cities of late medieval northern and central Italy. In addition to recording public and private legal acts, they also staffed dozens of minor offices and promoted a new way of doing politics that was increasingly based on ideas of public accountability. While the importance and lively intellectual culture of notaries have been long recognised, there has been a tendency to view these men (for they were exclusively men) mainly as the forerunners of modern administrators who contributed to the rise of the rational-bureaucratic state. This panel focuses on the connections notaries forged between cultural and professional interests. Through three different case studies, each treating different cities, we argue that notaries often drew on and blurred the boundaries between legal and extra-legal knowledge. Administrative documentation could become a space in which notaries articulated concerns about their place in society and reflected upon – or even critiqued – the rapidly changing political and social world of the late thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries. We embrace the alterity of premodern bureaucracies: our papers draw imaginatively upon evidence that, while often extraordinary in its survival, concerns practices and patterns of thought that were common to cities across late medieval Italy and much of the Mediterranean basin.

Lorenzo Caravaggi analyses extraordinary early fourteenth-century criminal sentences produced in Perugia and San Gimignano that were enriched with juridically-irrelevant narrative details. He argues that the notaries who staffed civic lawcourts might have participated in contemporary debates on the uncertainty of the law and judicial institutions.

Sarina Kuersteiner explores possible connections between the meaning of poems, contracts, and notarial self-images in the Memoriali registers of Bologna. Several notaries entered love poems of the Italian courtly tradition amidst contracts where both textual genres (poems and contracts) share the same official space, formulas, and layout.

Eric Nemarich’s paper turns to a highly unusual ‘anti-corruption’ investigation in fourteenth-century Lucca to examine how notaries could actively sabotage the work of the institutions they served, especially when that work was widely regarded as inimical to the welfare of Lucchese citizens.

Papers by Eric Nemarich

Speculum: A Journal of Medieval Studies, 2024

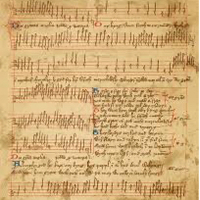

From the second half of the twelfth century until the late thirteenth century, the cathedral of N... more From the second half of the twelfth century until the late thirteenth century, the cathedral of Notre-Dame de Paris was the setting of a transformative episode in the history of music. On dozens of feast days in the cathedral’s liturgical year, the chants of the Mass and Office were sung in elaborate polyphony [organum]. The story of “Notre-Dame” polyphony is familiar, but it has had little to say about the musicians behind this repertory. This article reconstructs a small community of polyphonic masters—known, in Latin, as organistae— that took shape on the Left Bank of Paris between about 1190 and 1260. Scholars have come to imagine these musicians as the cathedral’s impoverished choral clerks, but I argue that organistae were supported, until about 1230, by lucrative ecclesiastical benefices; their lordly patrons were the bishops of Paris. Drawing upon newly uncovered archival evidence, I show that these ties to the cathedral began to fray in the 1230s and 1240s. In this period, I suggest, organistae pivoted away from the cathedral, finding new patrons in their own Left Bank neighborhoods. It was not until the 1260s, as they began to enter the ranks of Notre- Dame’s choral clergy, that organistae came to resemble the portrait of them that has prevailed in the scholarship. In general, this article argues that the cultivation of polyphony in thirteenth-century Paris was tied to the social world of organistae.

Uploads

Conference Presentations by Eric Nemarich

From at least the twelfth century notaries were central to the administration of the cities of late medieval northern and central Italy. In addition to recording public and private legal acts, they also staffed dozens of minor offices and promoted a new way of doing politics that was increasingly based on ideas of public accountability. While the importance and lively intellectual culture of notaries have been long recognised, there has been a tendency to view these men (for they were exclusively men) mainly as the forerunners of modern administrators who contributed to the rise of the rational-bureaucratic state. This panel focuses on the connections notaries forged between cultural and professional interests. Through three different case studies, each treating different cities, we argue that notaries often drew on and blurred the boundaries between legal and extra-legal knowledge. Administrative documentation could become a space in which notaries articulated concerns about their place in society and reflected upon – or even critiqued – the rapidly changing political and social world of the late thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries. We embrace the alterity of premodern bureaucracies: our papers draw imaginatively upon evidence that, while often extraordinary in its survival, concerns practices and patterns of thought that were common to cities across late medieval Italy and much of the Mediterranean basin.

Lorenzo Caravaggi analyses extraordinary early fourteenth-century criminal sentences produced in Perugia and San Gimignano that were enriched with juridically-irrelevant narrative details. He argues that the notaries who staffed civic lawcourts might have participated in contemporary debates on the uncertainty of the law and judicial institutions.

Sarina Kuersteiner explores possible connections between the meaning of poems, contracts, and notarial self-images in the Memoriali registers of Bologna. Several notaries entered love poems of the Italian courtly tradition amidst contracts where both textual genres (poems and contracts) share the same official space, formulas, and layout.

Eric Nemarich’s paper turns to a highly unusual ‘anti-corruption’ investigation in fourteenth-century Lucca to examine how notaries could actively sabotage the work of the institutions they served, especially when that work was widely regarded as inimical to the welfare of Lucchese citizens.

Papers by Eric Nemarich

From at least the twelfth century notaries were central to the administration of the cities of late medieval northern and central Italy. In addition to recording public and private legal acts, they also staffed dozens of minor offices and promoted a new way of doing politics that was increasingly based on ideas of public accountability. While the importance and lively intellectual culture of notaries have been long recognised, there has been a tendency to view these men (for they were exclusively men) mainly as the forerunners of modern administrators who contributed to the rise of the rational-bureaucratic state. This panel focuses on the connections notaries forged between cultural and professional interests. Through three different case studies, each treating different cities, we argue that notaries often drew on and blurred the boundaries between legal and extra-legal knowledge. Administrative documentation could become a space in which notaries articulated concerns about their place in society and reflected upon – or even critiqued – the rapidly changing political and social world of the late thirteenth and early fourteenth centuries. We embrace the alterity of premodern bureaucracies: our papers draw imaginatively upon evidence that, while often extraordinary in its survival, concerns practices and patterns of thought that were common to cities across late medieval Italy and much of the Mediterranean basin.

Lorenzo Caravaggi analyses extraordinary early fourteenth-century criminal sentences produced in Perugia and San Gimignano that were enriched with juridically-irrelevant narrative details. He argues that the notaries who staffed civic lawcourts might have participated in contemporary debates on the uncertainty of the law and judicial institutions.

Sarina Kuersteiner explores possible connections between the meaning of poems, contracts, and notarial self-images in the Memoriali registers of Bologna. Several notaries entered love poems of the Italian courtly tradition amidst contracts where both textual genres (poems and contracts) share the same official space, formulas, and layout.

Eric Nemarich’s paper turns to a highly unusual ‘anti-corruption’ investigation in fourteenth-century Lucca to examine how notaries could actively sabotage the work of the institutions they served, especially when that work was widely regarded as inimical to the welfare of Lucchese citizens.