Second-order cybernetics

New Cybernetics or second-order cybernetics is the cybernetics of cybernetics.[1][2] [3] [4]

It investigates the construction of models of cybernetic systems looking beyond the issues of the "first", "old" or "original" cybernetics and their politics and sciences of control, that the investigators are also part of the system, and of the importance of autonomy, self-consistency, self-referentiality, and self-organizing capabilities of complex systems.[5] Investigators of a system can never see how it works by standing outside it because the investigators are always engaged cybernetically with the system being observed; that is, when investigators observe a system, necessarily they affect it and are affected by it.

Contents

Overview

The so-called "new cybernetics" is an attempt to move away from the "old" cybernetics of Norbert Wiener. Old cybernetics is tied to the image of the machine and physics, whereas "second-order" new cybernetics closely resembles organisms and biology. The main task of the new cybernetics is to overcome entropy by using "noise" as positive feedback.[6]

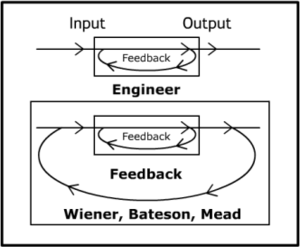

The anthropologists Gregory Bateson and Margaret Mead contrasted first and second-order cybernetics with this diagram in an interview in 1973.[7] It emphasises the requirement for a possibly constructivist participant observer in the second order case:

- ... essentially your ecosystem, your organism-plus-environment, is to be considered as a single circuit.[7]

Heinz von Foerster attributes the origin of second-order cybernetics to the attempts of classical cyberneticians to construct a model of the mind. Researchers realized that:

... a brain is required to write a theory of a brain. From this follows that a theory of the brain, that has any aspirations for completeness, has to account for the writing of this theory. And even more fascinating, the writer of this theory has to account for her or himself. Translated into the domain of cybernetics; the cybernetician, by entering his own domain, has to account for his or her own activity. Cybernetics then becomes cybernetics of cybernetics, or second-order cybernetics.[8]

The work of Heinz von Foerster, Humberto Maturana, Ranulph Glanville, and Paul Pangaro is strongly associated with second-order cybernetics. Gordon Pask recommended the term New Cybernetics in his last paper[9] which emphasises all observers are participant observers that interact.

Gertrudis van de Vijver stated in 1994 that the old cybernetics, the (second-order) new cybernetics and the cognitive paradigms are not that different from each other; and as is mostly the case, the so-called new paradigms are in a sense "older" than the "old" paradigms. The so-called "old" paradigms were in most cases strategically successful specializations in a general framework. Their success was based on a strong but useful simplification of the issues. The "new" paradigms are further specializations in the earlier one, or (as is mostly the case) a strategic retreat and introspection which broadens the specialized approach and is a return to the original, broader inspiration and outlook.[10]

History

In March 1946, the first of ten influential interdisciplinary Macy conferences were devoted to the "new cybernetics",[11] and opened with two presentations: the first by von Neumann on the new computing machines, followed by neurobiologist Lorente de No on the electric properties of the nervous system. These circuiting of analogies between behaviour of computers and the nervous system became central to cybernetic imagination and its founding desire to define the essential "unity of a set of problems" organized around "communication, control, and statistical mechanics, whether in the machine or living tissue. In particular, the early cyberneticists are convinced that research on computers and the organization of the human brain are one and the same field, that is, "the subject embracing both the engineering and the neurology aspect is essentially one."[12]

Wiener defined cybernetics in 1948 as the study of "control and communication in the animal and the machine". This definition captures the original ambition of cybernetics to appear as a unified theory of behaviour of living organisms and machines, viewed as systems governed by the same physical laws. The initial phase of cybernetics involved disciplines more or less directly related to the study of those systems, like communication and control engineering, biology, psychology, logic, and neurophysiology. Very soon, a number of attempts were made to place the concept of control at the focus of analysis also in other fields, such as economics, sociology, and anthropology. The ambition of "classic" cybernetics thus seemed to involve also several human sciences, as it developed in a highly interdisciplinary approach, aimed at seeking common concepts and methods in rather different disciplines. In classic cybernetics this ambition did not produce the desired results and new approaches had to be attempted in order to achieve them, at least partially.[13]

In the 1970s, New Cybernetics has emerged in multiple fields, first in biology. Some biologists influenced by cybernetic concepts (Maturana and Varela, 1980; Varela, 1979; Atlan, 1979) realized that the cybernetic metaphors of the program upon which molecular biology had been based rendered a conception of the autonomy of the living being impossible. Consequently, these thinkers were led to invent a new cybernetics, one more suited to the organization mankind discovers in nature – organizations he has not himself invented. The possibility that this new cybernetics could also account for social forms of organization, remained an object of debate among theoreticians on self-organization in the 1980s.[14]

In political science in the 1980s unlike its predecessor, the new cybernetics concerns itself with the interaction of autonomous political actors and subgroups and the practical reflexive consciousness of the subject who produces and reproduces the structure of political community. A dominant consideration is that of recursiveness, or self-reference of political action both with regard to the expression of political consciousness and with the ways in which systems build upon themselves.[5]

Geyer and van der Zouwen in 1978 discuss a number of characteristics of the merging "new cybernetics". One characteristic of new cybernetics is that it views information as constructed by an individual interacting with the environment. This provides a new epistemological foundation of science, by viewing it as observer-dependent. Another characteristic of the new cybernetics is its contribution towards bridging the "micro-macro gap". That is, it links the individual with the society. Geyer and van derZouten also noted that a transition classical cybernetics to the new cybernetics involves a transition form classical problems to new problems. These shifts in the thinking involve, among others a change emphasis on the system being steered to the system doing the steering, and the factors which guide the steering decisions. And new emphasis on communication between several systems which are trying to steer each other.[15]

In 1992, Pask summarized the differences between the old and the new cybernetics as a shift in emphasis:.[16][17]

- ... from information to coupling

- ... from the reproduction of "order-from-order" (Schroedinger 1944) to the generation of "order-from-noise" (von Foerster 1960)

- ... from transmission of data to conversation

- ... from external to participant observation – an approach that could be assimilated to Maturana and Varela's concept of autopoiesis.

New Cybernetics: Topics

Just as quantum theory has superseded classical physics, so the new cybernetics approach has superseded the classical theory of communication. According to F. Merrel (1988) in this new era, and speaking generally of the reigning conceptual framework, incompleteness, openness, inconsistency, statistical models, undecidability, indeterminacy, complementarity, polycity, interconnectedness, and fields and frames and references are the order of the day.[18]

Geyer & J. van der Zouwen (1992) recognize four themes in both sociocybernetics and new cybernetics:[2]

- An epistemological foundation for science as an observer-observer system. Feedback and feedforward loops are constructed not only between the observer, and the objects that are observed them and the observer.

- The transition from classical, rather mechanistic first-order cybernetics to modern, second-order cybernetics, characterized by the differences summarized by Gordon Pask.

- These problem shifts in cybernetics result from a thorough reconceptualization of many all too easily accepted and taken for granted concepts – which yield new notions of stability, temporality, independence, structure versus behaviour, and many other concepts.

- The actor-oriented systems approach, promulgated in 1978 made it possible to bridge the "micro-macro" gap in social science thinking.

Other topics where new cybernetics is developed are:

- Artificial neural networks[13]

- Living systems[19]

- New robotic approaches[13]

- Reflexive understanding[20]

- Political communication[21]

- Social dimensions of cognitive science[22]

- Sustainable development[4]

- Symbolic Artificial Intelligence[13]

- Systemic group therapy [23]

Organisational cybernetics

Organisational Cybernetics is distinguished from management cybernetics. Both use many of the same terms but interpret them according to another philosophy of systems thinking. Organizational cybernetics by contrast offers a significant break with the assumption of the hard approach. The full flowering of organizational cybernetics is represented by Beer's Viable System Model.[24]

Organizational Cybernetics (OC) studies organizational design, and the regulation and self-regulation of organizations from a systems theory perspective that also takes the social dimension into consideration. Researchers in economics, public administration and political science focus on the changes in institutions, organisation and mechanisms of social steering at various levels (sub-national, national, European, international) and in different sectors (including the private, semi-private and public sectors; the latter sector is emphasised).[25]

Sociocybernetics

The reformulation of sociocybernetics as an "actor-oriented, observer-dependent, self-steering, time-variant" paradigm of human systems, was most clearly articulated by Geyer and van der Zouwen in 1978 and 1986.[26] They stated that sociocybernetics is more than just social cybernetics, which could be defined as the application of the general systems approach to social science. Social cybernetics is indeed more than such a one-way knowledge transfer. It implies a feed-back loop from the area of application – the social sciences – to the theory being applied, namely cybernetics; consequently, sociocybernetics can indeed be viewed as part of the new cybernetics: as a result of its application to social science problems, cybernetics, itself, has been changed and has moved from its originally rather mechanistic point of departure to become more actor-oriented and observer-dependent.[27] In summary, the new sociocybernetics is much more subjective and the sociological approach than the classical cybernetics approach with its emphasis on control. The new approach has a distinct emphasis on steering decisions; furthermore, it can be seen as constituting a reconceptualization of many concepts which are often routinely accepted without challenge.[15]

See also

References

- ↑ Joseph Zeidner (1986), Human Productivity Enhancement, University of Michigan, p.173.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 R.F. Geyer and G. v.d. Zouwen (1992), "Sociocybernetics", in: Cybernetics and Applied Systems, C.V. Negoita ed. p.96.

- ↑ Anatol Rapoport eds.(1988), General Systems: Yearbook of the Society for the Advancement of General Vol 31, p.57.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Loet Leydesdorff (2001), A Sociological Theory of Communication: The Self-Organization of the Knowledge-Based Society. Universal Publishers/uPublish.com. p.253.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Peter Harries-Jones (1988), "The Self-Organizing Polity: An Epistemological Analysis of Political Life by Laurent Dobuzinskis" in: Canadian Journal of Political Science (Revue canadienne de science politique), Vol. 21, No. 2 (Jun., 1988), pp. 431–433.

- ↑ Tom Darby (1982), The Feast: Meditations on Politics and Time, p.220.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Interview with Gregory Bateson and Margaret Mead, CoEvolution Quarterly, June 1973.

- ↑ Von Foerster 2003, p.289.

- ↑ Pask, 1996.

- ↑ Gertrudis van de Vijver (1994), New Perspectives on Cybernetics: Self-Organization, Autonomy and Connectionism, p.97

- ↑ Karl M. Newell & Peter C. M. Molenaar (1998), Applications of Nonlinear Dynamics to Developmental Process Modeling, p.217.

- ↑ Roddey Reid & Sharon Traweek (2000), Doing Science + Culture, p.158.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Luciano Floridi (1993), The Blackwell Guide to the Philosophy of Computing and Information, pp.186–196.

- ↑ Jean-Pierre Dupuy, "The autonomy of social reality: on the contribution of systems theory to the theory of society" in: Elias L. Khalil & Kenneth E. Boulding eds., Evolution, Order and Complexity, 1986.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Kenneth D. Bailey (1994), Sociology and the New Systems Theory: Toward a Theoretical Synthesis, p.163.

- ↑ Alessio Cavallaro, Annemarie Jonson, Darren Tofts (2003), Prefiguring Cyberculture: An Intellectual History, MIT Press, p.11.

- ↑ Evelyn Fox Keller, "Marrying the premodern to postmodern: computers and organism after World War II", in: M. Norton. Wise eds. Growing Explanations: Historical Perspectives on Recent Science, p 192.

- ↑ Merrel, F., "An Uncertain Semiotic", in: The Current in Criticism, eds. V. Lokke and C. Koelb, West Lafayette: Purdue University Press, 1987, p.252

- ↑ Rachelle A. Dorfman (1988), Paradigms of Clinical Social Work, p.363.

- ↑ Policy Sciences, Vol 25, Kluwer Online, p.368

- ↑ D. Ray Heisey (2000), Chinese Perspectives in Rhetoric and Communication, p.268.

- ↑ Margaret A. Boden (2006), Mind as Machine: A History of Cognitive Science, p.203.

- ↑ Roland Littlewood, "Social Trends and psychopathology", in: Jonathan C. K. Wells ea. eds., Information Transmission and Human Biology, p. 263.

- ↑ Michael C. Jackson (1991), Systems Methodology for the Management Sciences.

- ↑ Organisational Cybernetics, Nijmegen School of Management, The Netherlands.

- ↑ Lauren Langman, "The family: a 'sociocybernetic' approach to theory and policy", in: R. Felix Geyer & J. van der Zouwen Eds. (1986), Sociocybernetic Paradoxes: Observation, Control and Evolution of Self-Steering Systems, Sage Publications Ltd, pp 26–43.

- ↑ R. Felix Geyer & J. van der Zouwen Eds. (1986), Sociocybernetic Paradoxes: Observation, Control and Evolution of Self-Steering Systems, Sage Publications Ltd, 248 pp.

Citation and further reading

- Heinz von Foerster (1974), Cybernetics of Cybernetics, Urbana Illinois: University of Illinois.OCLC 245683481

- Heinz von Foerster (1981), 'Observing Systems", Intersystems Publications, Seaside, CA. OCLC 263576422

- Heinz von Foerster (2003), Understanding Understanding: Essays on Cybernetics and Cognition, New York : Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-0-387-95392-2

- Humberto Maturana and Francisco Varela (1988). "The Tree of Knowledge", Shambhala, Boston and London.

- Humberto Maturana and Bernhard Poerksen (2004), "From Being to Doing". Carl-Auer Verlag, Heidelberg.

- Gordon Pask (1996). Heinz von Foerster's Self-Organisation, the Progenitor of Conversation and Interaction Theories, Systems Research 13, 3, pp. 349–362

- Scott, B. (2001). Conversation Theory: a Dialogic, Constructivist Approach to Educational Technology, Cybernetics and Human Knowing, 8, 4, pp. 25–46.

- William Irwin Thompson (ed.), (1987), 'Gaia - a way of knowing". Lindisfarne Press, New York.

- Francisco Varela (1991), "The Embodied Mind", MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

- Francisco Varela, (1999), "Ethical Know-How", Stanford University Press.

- Laurent Dobuzinskis (1987), The New Cybernetics and the Science of Politics an Epistemological Analysis, Westview Press, pp. 223.

- Richard F. Ericson (1969). Organizational cybernetics and human values. Program of Policy Studies in Science and Technology. Monograph. George Washington University.

- F. Heylighen, E. Rosseel & F. Demeyere Eds. (1990), Self-steering and Cognition in Complex Systems: Toward a New Cybernetics, Gordon and Breach Science Publishers, New York, 432 pp.

- Stuart Umpleby (1989), "The science of cybernetics and the cybernetics of science", in: Cybernetics and Systems", Vol. 21, No. 1, (1990), pp. 109–121.

- Karl H. Müller (2008), The New Science of Cybernetics. The Evolution of Living Research Designs, vol. I: Methodology. Vienna:edition echoraum

- Ralf-Eckhard Türke (2008), A second-order notion of Governance: Governance - Systemic Foundation and Framework (Contributions to Management Science, Physica of Springer, 2008) ISBN 978-3-7908-2079-9

External links

- Principia Cybernetica

- Cybernetics and Second-Order Cybernetics

- New Order from Old: The Rise of Second-Order Cybernetics and Implications for Machine Intelligence

- Constructivist Foundations, a peer-reviewed electronic journal dedicated to constructivism, second-order cybernetics, and related disciplines.

- Heinz von Foerester's Self Organization

- Cybernetic Orders

- History of organizational events of the American Society of Cybenertics. In 1981 the title of the ASC conference was "The New Cybernetics", Oct. 29 – Nov. 1, GWU, Washington, DC (chair Larry Richards, local arrangements Stuart Umpleby).