This is the first book of a trilogy.

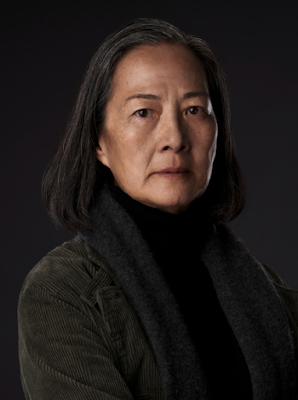

Note: I initially read a hard copy of this book and recently listened to the audiobook, which became available on Netgalley. I especially appreciated hearing the pronunciation of Chinese names and words. The book is narrated by Rosalind Chao, who does a fine job.

The story begins during the early years of China's 'Cultural Revolution.' Ye Wenjie, a young astrophysicist, sees her father - a physics professor - tortured and murdered by a group of young Red Guards.

Like many educated citizens Ye Wenjie is labeled a 'counter-revolutionary' and sent to cut trees for the Construction Corps before being recruited to work at a secret facility called Red Coast Base.

At first Ye Wenjie has limited access to the base's surreptitious activities but in time her abilities and intelligence give her wide access to the installation. Over time Ye Wenjie makes some startling discoveries and engages in some questionable behavior. (To say more would lead to spoiler territory.)

Some years later, when the Cultural Revolution wanes, Ye Wenjie is allowed to return home and become a university professor.

In current times an applied physicist named Wang Miao - who's developed a very strong nanomaterial - is recruited by a committee composed of military officers/police. They ask Wang to help investigate a rash of physicist suicides.

Wang reluctantly agrees and is assisted by a suspended cop called Da Shi - a disheveled, abrasive, pushy, off-putting guy.

>

>As things turn out though, Da Shi's ability to think outside the box is useful and his common sense is comforting....so I developed quite a liking for the fellow.

While Wang Miao is looking into the physicist suicides he develops peculiar/frightening 'vision problems' and starts to play an immersive computer game called "Three Body."

The game is set on Trisolaris, a distant planet inhabited by extraterrestrials. Trisolaris has a very unstable environment. During 'chaotic periods' (extremely hot or cold) most Trisolarans are dehydrated, rolled up, and stored in dehydratories. During 'stable periods' (mild weather) the Trisolarans are rehydrated and go about their business. Still, there are frequent 'crashes' when the entire Trisolaran civilization is destroyed and has to start over.

The shifts between chaotic and stable periods on Trisolaris are completely random and abrupt. Thus the player's goal is to discover why they happen and to predict long-term stable periods. Wang determines that the chaos occurs because the planet has three suns....thus the 'three-body problem.' [Note: On the internet the three-body problem is defined as follows: "the problem of taking an initial set of data that specifies the positions, masses and velocities of three bodies for some particular point in time and then determining the motions of the three bodies, in accordance with Newton's laws of motion and universal gravitation."] In essence it's almost impossible to accurately predict the motion of Trisolaris' three suns.....but Wang Miao thinks he can do it.

As the story continues to unfold it turns out that Ye Wenjie's experiences at Red Coast Base, the physicist suicides, Wang Miao's nanomaterial research, and the three-body game are all connected. And they have something to do with the fact that humans have managed to contact an alien civilization. (Again, more information would be a spoiler.)

The story addresses an interesting topic: how would people react if they knew there were other intelligent beings in the universe? And what would happen if the other beings were on their way here? (I've always thought extraterrestrials - if they found out about Earth - might come here, wipe us out, and move in. But maybe that's just me....LOL)

There's a lot of physics jargon in the book and some fancy shenanigans with protons that stretch suspension of disbelief to the max...even for sci-fi.

In the end, though, I enjoyed the book very much. China provides a great (and unusual) background for a science fiction book and the story is riveting, with interesting characters. Highly recommended to fans of science fiction.

I look forward to reading the rest of the trilogy.

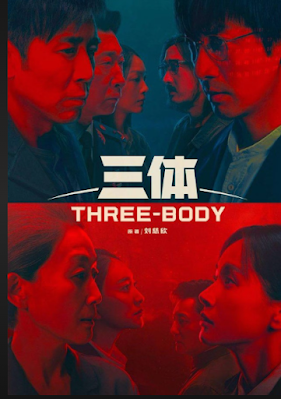

The story is being adapted for a series on Netflix.

Thanks to Netgalley, Cixin Liu, and Macmillan Audio for a copy of the audiobook.