On Gustave Moreau

Sign up for access to the world's latest research

Abstract

An introduction to the work of noted artist, Gustave Moreau through the context of art history - an article review.

Related papers

2018

In 1890, Gustave Moreau received the commission to create a painting that would ultimately become his last masterpiece. Secluded in his large studio on the Rue de la Rochefoucauld, accompanied only by a few faithful assistants and living out his last days alone (his mistress of twenty-five years having died the year the painting was begun...) Moreau became lost in the labyrinth of his own creation. The final result was an enigmatic opus, intriguing but bewildering. His admirers hailed him as a genius, while his critics branded him as an eccentric and recluse, a consumer of opium and hashish... Now, calling upon texts written by Moreau himself, the noted author L. Caruana elucidates the painting, offering a visual journey through its narrative, composition and philosophy. Through a close examination of the details and comparing them to the painting as a whole, Moreau’s vast allegory emerges – a timeless myth, Neo-Platonic and Gnostic in conception, of the soul’s separation from divinity, its entrapment in matter, and even its possible incarceration in the underworld. Yet, Moreau’s altarpiece also offers us a rare moment of revelation and redemption, an ascent to the higher realm where beauty, perfection and timeless archetypes eternally dwell. The second half of this brief study (elaborately illustrated in black and white) explores the painting’s evolution, offering photos of its different stages, identifying lines of armature and explaining the harmonic proportions underlying its composition. The artist’s working methods are examined – his use of plasticine models, photographs and live models – and the alterations (pentimenti) in the painting. Finally, Moreau’s own aspirations to extend Historical Painting into a higher kind of Spiritual and Allegorical Painting (which he called Le Grand Art) are revealed through original translations of the artist’s texts, including fragments of a self-written obituary (nécrologie).

ARS, 2021

This is the translated version of a paper originally published in portuguese as Modernidade e desmaterialização na pintura tardia de Gustave Moreau. ARS (São Paulo), 19(41), 306-336. https://doi.org/10.11606/issn.2178-0447.ars.2021.180960 In his final phase, Gustave Moreau's work goes through a process of dematerialization which is common to other artists of his generation. By analysing the painting and personal notes of Moreau, this paper searches to understand the artistic strategies and theoretical implications involved in this movement of idealizing the concept of "work of art"; here are discussed the symbolically charged use of the unfinished in painting and the decentralization of the "work", unfolded into multiple sketches and minor studies. Using the artist's case as a starting point, it also seeks to contribute to a general perspective on key issues of modern painting.

Land of Myths. The Art of Gustave Moreau. Exhib. cat. Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest, 2009

Gustave Moreau was the first true symbolist painter and the idol of a successful and large circle of artists which instead of exploring nature delved into the world of mystery. It was a surprise when after 1880, at the peak of his success, he permanently retreated from public appearances, shutting himself away from the outside world to create works of art for himself. The pictorial effect of the works Moreau created in seclusion, away from the eyes of the public at which time he was able to ignore any outer respect displays far greater courage than his earlier pieces displayed to the public. A certain group of works found among the relaxed sketches and inventive technical experiments in Gustave Moreau’s studio museum comes as a real surprise to the visitor who sees it several generations after the artist died. The almost two hundred undated pictures are entitled in the inventory as “Sketches” and according to the artistic concepts of the 20th century they can be described as genuine abstract compositions.

Related topics

Related papers

2014

benefit to me, especially in the final stages-as were his careful and generous (re)readings of the text. Susan Siegfried and Michèle Hannoosh were also early mentors, first offering inspiring coursework and then, as committee members, advice and comments at key stages. Their feedback was such that I always wished I had solicited more, along with Michèle's tea. Josh Cole's seminar gave me a window not only into nineteenth-century France but also into the practice of history, and his kind yet rigorous comments on the dissertation are a model I hope to emulate. Betsy Sears has also been an important source of advice and encouragement. The research and writing of this dissertation was funded by fellowships and grants from the Georges Lurcy Foundation, the Rackham Graduate School at the University of Michigan, the Mellon Foundation, and the Getty Research Institute, as well as a Susan Lipschutz Award. My research was also made possible by the staffs at the Bibliothèque nationale de France, the Institut nationale d'Histoire de l'Art, the Getty Research Library, the Musée des arts décoratifs/Musée de la Publicité, and the Musée Maurice Denis, iii among other institutions. Special thanks go to a number of individuals who provided particular assistance. I would like to express my gratitude to the late Françoise Cachin for allowing me access to the Signac Archives and to Marina Ferretti-Bocquillon for devoting her time to those archival visits and to subsequent questions and requests, as well as to Charlotte Liébert Hellman for related permission requests. At the Musée Maurice Denis, Marie El Caïdi could not have been more welcoming and informative, while Fabienne Stahl, working nearby on the artist's catalogue raisonnée, has been generous both with information and images. Others I would like to thank for research assistance are Michèle Jasnin and Virginie Vignon at the Musée de la Publicité, Anne-Marie Sauvage at the BN's Département des estampes et de la photographie, as well as Laurence Camous and François-Bernard Michel. I would also like to take the opportunity to highlight three professional opportunities that played a particularly strong role in furthering my reflection, and the people who made those opportunities possible. New Directions in Neo-Impressionism, organized by Tania Woloshyn and Anthea Callen at Richmond, the American International University in London on November 20, 2010 led to an issue of the same name in RIHA Journal, edited by Woloshyn and Anne Dymond. Their feedback on my submission, along with that of Robyn Roslak was instrumental in shaping the core of chapter three (which also benefitted from editing by Regina Wenninger). Having welcomed my attendance at sessions of her graduate seminar, Ségolène Le Men kindly invited me to contribute to a stimulating Journée d'étude (Jules Chéret, un pionnier à la iv croisée de l'art décoratif et de l'affiche) at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs on October 20, 2010, she co-organized with Réjane Bargiel in conjunction with the museum's exhibition of the artist's work. This experience, as well as the exhibition itself and its catalog/catalogue raisonnée, helped me to define the argument(s) of chapter two. It also led to many fruitful discussions on posters and other subjects with Karen Carter. Chapter two has also benefitted from thinking and research prompted by my contribution to a forthcoming volume edited by Anca I.

Exh.-Cat. Praised and Ridiculed. French Painting 1820-1880, ed. by Sandra Gianfreda, Kunsthaus Zürich, 10.11.2017-28.01.2018, Munich 2017, p. 44-55 (228-230) (engl. ed.)

By the 1730s a new generation of French painters had developed a renewed understanding of history painting. This reconceptualization undermined the foundations of Albertian historia and the underpinnings it had for so long provided for the practice and theory of French grand genre. Representing figures defined by dramatic actions and narrative relationships between them was replaced by a mode of presenting figures in quieter states of bodily and psychological introspection. This naturally recalls Michael Fried’s notion of ‘absorption’, used to define a pictorial aesthetic that emerged in the mid-eighteenth century. This essay maps the earlier appearance of such ‘absorptive states’, where the valorization of inner mental activities coincided with a growing singularization of the figures within a composition. This phenomenon, it is argued, was the result of an evolution in the academic practice of life drawing. This led to an even-greater attention to the figuration of the human body in painting as the manifestation of an interior state, becoming the central organizing principle of history painting.

The objective of this paper is to analyze the psychology behind paintings created in the 19 th century by French painters. Painters usually portray what they feel or see in their personal point of view. This paper will cover two paintings where you can appreciate an uncovered or an obvious demonstration of a certain social situation from the artist`s perspective. It will be especially of French artists because of the interesting social situation France was experiencing in this century. Since the paper is mainly about understanding what the mind of these famous artists were about, there will be a brief timeline of the most significant political French events of the 19 th century. The timeline's purpose is to have some key points regarding the situation of the country in general. Considering that the two paintings are going to cover mostly social events, the previous it's important. After acknowledging these, a list (not detailed) of the artistic movements bestowed in the century will be presented. The painters will be mentioned with their painting about the social issue. Merging the social issue shown and the data recollected of their particular situation (life conditions, individual thoughts and particular artistic influences), a conclusion based on the behavior of the subject will likely describe what could most possibly had been through their minds.

Bryan Jackson

Modernism

**On Gustave Moreau – Article Review**

What the article begins with is to express a great dynamism and duality that existed during the time of historical paintings and the inherent friction between practitioners of the style such and the reigning academic trends and demands of the artistic establishment. Moreau was, by all accounts, a classicist whose adherence to narrative as a motivator of understanding was evident within his works but also apparent in his training and those he studied under. Yet despite his clear allegiance, he rejected many of the departures utilized by numerous contemporaries and instead continued on with what he regarded as ‘Le Grande Art’ - sweeping, melodramatic scenes that imply so much more than that which is presented with a strong emphasis on figure and anatomy. “History painting is a narrative genre that traditionally involves the dramatic staging of figures engaged in significant actions. In academic training and practice, the theatrical paradigm, according to which 'a picture should be considered as a stage on which each figure plays its role.”, according to Cooke. He then goes to great lengths to convince the reader that historical art was an amalgamation of several things competing for the attention of the viewer, reading a book as opposed to a word and this complexity provides great depth along with an intimate connection not only to its subject matter, but also the audience interpreting the work so long as they have the correct knowledge. Moreau felt that there should be a natural balance that brings the entire work into view as one body, not just hollow components of humanity against the circumstances depicted. He felt that the overuse of majestic elements and elaborate backgrounds, colors, techniques while useful, effectively muted the narrative and rendered the art summarily meaningless if unevenly applied. As evidenced by the quote, “The theater in the plastic [or pictorial] arts: an idiotic and childish mixture.” (cite) this was not something lamented early on in his artistic or academic career but at the culmination of his study beneath Francois Édouard Picot in preparation for the École de Beau-Arts in Paris while steeped amongst similarly-minded company. Indeed, this was not a conclusion reached suddenly but rather, a curated opinion grown out of lifelong exposure to his genre.

The article then goes on to discuss the contemporary attitudes on historical painting as put forth by Moreau’s peers, such as Èlie Delaunay’s Death of Nessus – who selected a mythological backdrop, which while containing a narrative in the form of the arrow striking the centaur, lacks the contextual depth Moreau believed was essential in historical painting while retaining the romantic elements necessary for dramatic impact. While acclaimed by some, others such as Mènard indicated that the background detracted from the form and figures present as an unnecessary embellishment that was diminished by the emphasis placed upon it by the artist. Nevertheless, Delaunay’s painting while flawed is effective from a critical standpoint reflecting the tastes of the time although certain aspects of it confound the viewer in a mess of lines and assumptions. Hercules’ mortal wound inflicted upon Nessus, who then presumably drops Deianira who will then be rescued would only be known to those who have a presupposed grasp of mythology and would not make sense to those who don’t. At that point, understanding and interpretation is reduced to a small audience who would have access to this degree of education on antiquity, the classics, various legends. The simplicity of the drama evidenced by following the figures and actions are viewed as a departure from the high-minded established style of the historical painting of seventeenth century of France as exemplified by Nicolas Poussin. It is conveyed to us, as readers that the former espoused three distinct elements; the event being depicted, the consequences arising from the presented action and finally, the moral implications resulting from the meeting of the first two. Conversely, mid-nineteenth century historical paintings tended to focus on easily digestible single-scene depictions in progress or about to occur – far less complex.

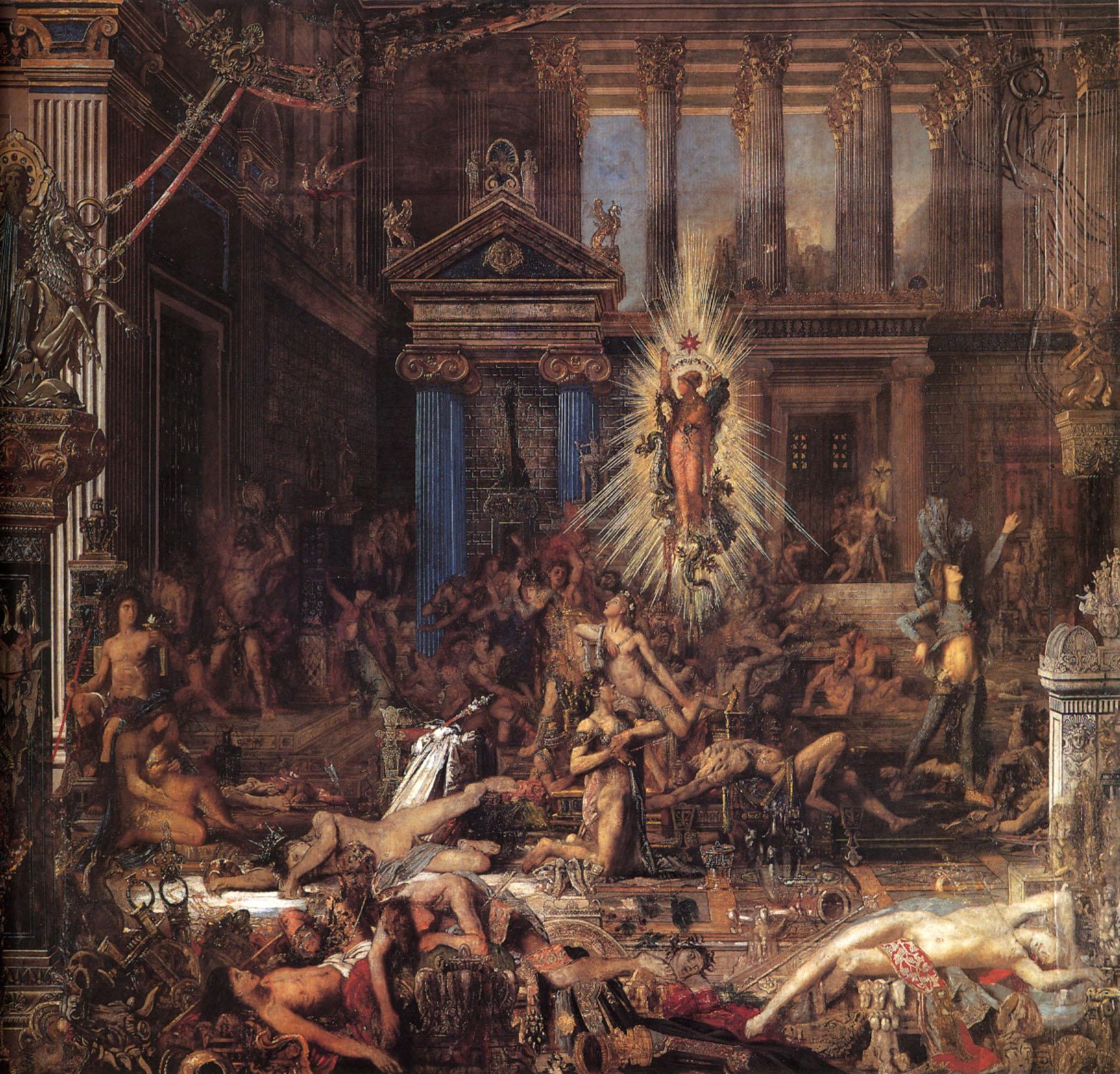

Poussin intended his work to be reserved for the erudite – the learned and saw the canvas as an author of an epic might view their written works, as a means of conveyance rather than a simple destination. Indeed, a noted contemporary of Poussin regarded his work as that of a ‘painter-philospher’, who, as quoted, “he gave to ideas rather than painting to demands.” (Cooke, 2014) It is clear via the next example that Moreau’s intention was not necessarily to emulate Poussin’s style, but to revive it as a way to displace the unsophisticated entries that were put forth by his contemporaries and was tragically accepted by the society in which he existed. His solution to this quandary was present in his depiction of *The Suitors*, the inspiration for which was taken directly from The Odyssey in which Ulysses had returned to Ithaca and mercilessly slew the collection of princes who had come to the palace under the pretext of courting and eventually marrying his wife in the event of news of his death. Moreau presented his work as the renaissance masters might have – the religious imagery was blatant but not explicitly secular as it focused on the former pagan traditions as evidenced by the divine light shining forth from Minerva, goddess of wisdom lording over the fracas. There are certain tells that borrow heavily from the styles of the past, such as the Doric columns in the background providing a sense of depth and grandness, the friezes and the elaborate stonework. All of these traits serve to further deepen the connection to the culture the painting is enshrining with regard that isn’t subtle, but not overt – it’s the perfect balance of narrative and artistic mastery. In this way, Moreau avoids being in the same class as his peers, but above them – he’s taken the best parts of the origin of the genre and blended it effectively with the contemporary artistic attitudes of his age. The author then goes on to elaborate significantly upon the blending of early Italian Renaissance influence and current 19^{th} century artistic paradigms as a point of juxtaposition and resultant tension, which set his work apart from nearly all others.

In justification of the massive conflagration of figures, forms, emotion, background, light, grandeur and sheer style, Moreau believed, as the article states, "Moreau reveals a far deeper interest in rendering something much more subtle and intangible; an intimate, tmmotivated state of mind that he calls “inner flashes,” a sublime psychological and aesthetic state to be conveyed by “the marvelous effects of pure pictorial beauty.” (Cooke, 2014) In this way, Moreau is esconced by the three major tenets mentions in the paragraph above and he applies them in such a way that this work becomes a major divergence point. “Thus, in eloquent prose, Moreau juxtaposes three aesthetic aims: the expression of the passions through the representation of dramatic human action; the creation of calm pictorial beauty, engendered by the immobile human body; and the evocation of an immaterial state that he considers sublime. Moreau was to pursue these last two aims throughout his career.” (Cooke, 2014)

*The Suitors* by Gustave Moreau. Begun 1852 or 1853. Oil on canvas, 11 feet 5 inches x 12 feet 5 1/2 inches. Musée Gustave-Moreau, Paris.

Despite the clear gains expressed within the creation of this work, it was never displayed, remaining in Moreau’s studio as an unfinished product that never quite went to market. His entry instead was *Oedipus and the Sphinx*, which was exhibited in its place. This entry was intended to clash directly with Ingres’ *Oedipus Explaining the Riddle of the Sphinx*, a similarly themed entry that showed the character in the underworld discussing the solution to the riddle amongst intrigued inhabitants. This was in effect Moreau’s defining work that showed the genius of the concept of contemplative immobility, figures which while rigid, convey a sense of movement and idealization of the human form. As he continued to experiment further with styles that directly and publicly clashed with his peers, he continued to delve deeper into a broadening sense of iconography which became increasingly evident giving rise to a number of spiritually-inspired artistic tropes – Salome and the concept of the recurring ‘femme fatale’. It is this symbolism that allowed him to explore things that his peers were slavishly prevented from doing due to their adherence to style and refusal to depart for fear of being professionally ostracized. Furthermore, it is also this risk-taking that empowered Moreau to further his own experimentation, becoming increasingly more comfortable incorporating them into his works.

The entire article is expressing the state of historical painting during the lifetime of Gustave Moreau and illustrating where – and how – Moreau leaves these conventions in favor of his own take on the genre and in doing so, stole it away and redefined it once more in his own image, indeed, le grand art… Is the article effective? Yes – quite so because not only do we see the differences in the work product from both Moreau and his peers, with Cooke’s advisement, we are also able to see where the overlap is and thus conduct a comparative analysis. He did not completely abandon the guiding artistic principles of his era, he adapted them into his own vision and injected his own ideas on spirituality into his themes, impressing his own take on not only the field of historical painting as a genre, but the legends and scenes selected for further illustration.

**Reference:**

Cooke, Peter. *Gustave Moreau History Painting, Spirituality and Symbolism*. Yale University Press, 2014.

Bryan R Jackson A.A., BFA, M.Ed.

Bryan R Jackson A.A., BFA, M.Ed.