Annual Reviews

www.annualreviews.org/aronline

Annu.Rev. EarthPlanet. Sci. 1995.23:451-78

Copyright(~ 1995by AnnualReviewsInc. All rights reserved

Annu. Rev. Earth. Planet. Sci. 1995.23:451-478. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.org

by Columbia University on 09/17/05. For personal use only.

SEQUENCE STRATIGRAPHY

Nicholas Christie-Blick

and Neal W. Driscoll

Departmentof Geological Sciences and Lamont-DohertyEarth Observatory

of ColumbiaUniversity, Palisades, NewYork 10964-8000

KEYWORDS:

sedimentation, unconformity, tectonics, seismic stratigraphy, sea level

INTRODUCTION

Sequencestratigraphy is the study of sedimentsand sedimentaryrocks in terms

of repetitively arranged facies and associated stratal geometry(Vail 1987;Van

Wagoneret al 1988, 1990; Christie-Blick 1991). It is a technique that can be

traced back to the workof Sloss et al (1949), Sloss (1950, 1963), and Wheeler

(1958) on interregional unconformitiesof the NorthAmericancraton, but it becamesystematizedonlyafter the advent of seismicstratigraphy, the stratigraphic

interpretation of seismicreflection profiles (Vail et al 1977, 1984, 1991;Berg

&Woolverton1985; Cross &Lessenger 1988; Sloss 1988; Christie-Blick et al

1990; Van Wagoneret al 1990; Vail 1992). Sequencestratigraphy makesuse of

the fact that sedimentarysuccessions are pervadedby physical discontinuities.

Theseare present at a great range of scales and they arise in a numberof quite

different ways:for example,by fluvial incision and subaerial erosion (abovesea

level); submergenceof nonmarineor shallow-marinesediments during transgression (flooding surfaces and drowningunconformities), in somecases with

shoreface erosion (ravinement); shoreface erosion during regression; erosion

in the marineenvironmentas a result of storms, currents, or mass-wasting;and

through condensation under conditions of diminished sediment supply (intervals of sedimentstarvation). The mainattribute shared by virtually all of these

discontinuities, independentof origin and scale, is that to a first approximation

they separate older deposits from youngerones. The recognition of discontinuities is therefore useful because they allow sedimentarysuccessions to be

divided into geometrical units that have time-stratigraphic and hence genetic

significance.

Precise correlation has of course long been a goal in sedimentarygeology,

and the emergenceof sequence stratigraphy does not imply that existing techniques or data oughtto be discarded. Instead, sequencestratigraphy provides a

451

0084-6597/95/0515-0451$05.00

�Annual Reviews

www.annualreviews.org/aronline

Annu. Rev. Earth. Planet. Sci. 1995.23:451-478. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.org

by Columbia University on 09/17/05. For personal use only.

452

CHRISTIE-BLICK& DRISCOLL

unifying frameworkin whichobservationsof intrinsic properties such as lithology, fossil content, chemistry, magneticremanence,and age can be compared,

correlated, and perhaps reevaluated. Withthe possible exception of sedimentar), units characterized by tabular layering over large areas and by the absence

of significant facies variation (for example,somedeep-oceanicsediments),

is hard to imagineattemptingto interpret the stratigraphic record in any other

context. Wemakethis point because criticisms leveled at sequencestratigraphy

havetended to lose sight of the essence of the technique.

In this regard, it is unfortunate that the developmentof sequencestratigraphy has coincided with the reemergenceof the notion that in marine and

marginal marine deposits sedimentary cyclicity is due primarily to eustatic

change (Vail et al 1977; Haq et al 1987, 1988; Posamentieret al 1988; Sarg

1988; Dott 1992). Eustasy (global sea-level change) mayin fact have modulated

sedimentationduring muchof earth history but, as a practical technique and in

spite of terminologycurrently in use, sequencestratigraphy does not actually

require any assumptionsabout eustasy (Christie-Blick 1991). Indeed, one of the

principal frontiers of this discipline today is the attempt to understandpatterns

of sediment transport and accumulation as a dynamic phenomenongoverned

by a great manyinterrelated factors.

In mostcases, specific attributes of sedimentarysuccessions(for example,the

lateral extent and thickness of a sedimentaryunit, the distribution of included

facies, or the existenceof a particular stratigraphic discontinuity) cannot be ascribed confidentlyto a single cause. In particular, the roles of"tectonic events,"

eustatic change, and variations in the supply of sediment can be partitioned

only with difficulty (Officer &Drake1985, Schlanger1986, Burtonet al 1987,

Cloetingh 1988, Kendall & Lerche 1988, Galloway 1989, Cathles & Hallam

1991, Christie-Blick 1991, Reynoldset al 1991, Sloss 1991, Underhill 1991,

Kendallet al 1992, Karneret al 1993, Steckler et al 1993, Driscoll et al 1995).

Eachof these factors operates at a broad range of time scales (cf Vail et al

1991), and none is truly independent owing to numerousfeedbacks. For example, the accumulation of sediment produces a load, which in manycases

significantly modifies the tectonic componentof subsidence (Reynoldset al

1991, Steckler et al 1993, Driscoll & Karner 1994). The space available for

sedimentto accumulateis therefore not simplya function of somepoorly defined

combinationof subsidence and eustasy (the now-popularconcept of "relative

sea-level change") because that space is influenced by the amountof sediment

that actually accumulates.

As a result of feedbacks, there are also inherent leads and lags in the sedimentary system; these influence the timing of the sedimentary response to

any particular driving signal in waysthat are difficult to predict quantitatively

(Jordan & Flemings 1991, Reynolds et al 1991, Steckler et al 1993). This

phenomenon

is particularly significant for efforts to sort out the role of eustasy

�Annual Reviews

www.annualreviews.org/aronline

Annu. Rev. Earth. Planet. Sci. 1995.23:451-478. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.org

by Columbia University on 09/17/05. For personal use only.

SEQUENCESTRATIGRAPHY 453

(e.g. Christie-Bliek 1990, Christie-Blick et a11990,Watkins&Mountain1990,

Loutit 1992). If the phaserelation betweenthe eustatic signal and the resulting

stratigraphic record varies from one place to another, then the synchronyor

lack thereof of observedstratigraphic events mayprove to be less useful than

previouslythought as a criterion for distinguishing eustasy fromother controls

on sedimentation. At the very least, the.comparisonof sites needsto take into

accountthe other importantvariables.

Recognitionof these inherent difficulties has led to a gradualshift in research

objectives awayfrom such goals as deriving a "sea-level curve," and toward

studies designedto investigate the effects of specific factors ki~ownto have

been important in governing sedimentation in a particular sedimentary basin

or at a particular time in earth history. Among

the most important factors are

the rates and amplitudesof eustatic change,subsidencepatterns in tectonically

active and inactive basins, sedimentflux or availability, the physiographyof

the depositional surface (for example,rampsvs settings with a well-developed

shelf-slope break), and scale. The subdiscipline of high-resolution sequence

stratigraphy has emergedin the course of this research partly in response to

the need for detailed reservoir stratigraphy in maturepetroleumprovinces and

partly becausemanyof the interesting issues needto be addressedat an outcrop

or boreholescale (meters to tens of meters) rather than at the scale of a conventional seismic reflection profile (Plint 1988, 1991; VanWagoneret al 1990,

1991; Jacquin et al 1991; Leckie et al 1991; Mitchum& Van Wagoner1991;

Posamentier et al 1992a; Flint &Bryant 1993; Garcia-Mond6jar&Fern~indezMendiola 1993; Johnson 1994; Posamentier & Mutti 1994). Another frontier

in sequencestratigraphy is the application of sequencestratigraphic principles

to the study of pre-Mesozoic successions (e.g. Sarg &Lehmann1986; Lindsay 1987; Christie-Blick et al 1988, 1995; Grotzinger et al 1989; Sarg 1989;

Ebdonet al 1990; Kerans &Nance 1991; Levy & Christie-Blick 1991; Winter

& Brink 1991; Bowring& Grotzinger 1992; Holmes& Christie-Blick 1993;

Lindsay et al 1993; Sonnenfeld & Cross 1993; Southgate et al 1993; Yang&

Nio 1993). In spite of its roots in Paleozoicgeology(Sloss et a11949),sequence

stratigraphy has been undertaken primarily in Mesozoicand Cenozoicdeposits

owingto the greater economicsignificance, more complete preservation, and

amenabilityto precise dating of sedimentsand sedimentaryrocks of these eras.

However,applications to older successions within the past decadehave provided

important new perspectives about the developmentof individual sedimentary

basins, as well as data relevant to manyof the issues outlined above.

Standard concepts and the basic methodologyof sequence stratigraphy are

describedin numerous

articles, especially those by Haqet al (1987), Vail (1987),

Baum&Vail (1988), Loutit et al (1988), Van Wagoneret al (1988, 1990),

Posamentieret al (1988), Sarg (1988), Haq(1991), and Vail et ai (1991).

this review, we have chosento emphasizeareas of disagreementor controversy,

�Annual Reviews

www.annualreviews.org/aronline

454

CHRISTIE-BLICK& DRISCOLL

especially with respect to the origin of stratigraphic discontinuities, whichwe

think is one of the mostinteresting general issues in sedimentarygeology.

Annu. Rev. Earth. Planet. Sci. 1995.23:451-478. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.org

by Columbia University on 09/17/05. For personal use only.

CHOICE OF A FRAMEWORKFOR

SEQUENCE STRATIGRAPHY

The objective of sequencestratigraphy is to determinelayer by layer howsedimentarysuccessionsare put together, from the smallest elementsto the largest.

Weare thus interested in all of the physical surfaces that at different scales

separate one depositional element from another, and it could be argued that

disagreements about how elements are defined and combinedare secondary

to the overall task at hand. Indeed, different perceptions are in part a product of real differences that haveemergedin the study of contrasting examples.

However,it is clear that stratigraphy represents morethan a series of random

events. In manycases there exists a definite hierarchy in layering patterns. In

choosing a frameworkfor sequence stratigraphy, it is therefore important to

select elements that are as far as possible genetically coherent and not merely

utilitarian. Currently, at least three schemesare being used (Figure 1). Here

we briefly makethe case for the form of sequence stratigraphy that emerged

from Exxonin the 1970s and 1980s (Vail et al 1977, 1984; Vail 1987; Sarg

1988; VanWagoneret al 1988, 1990), in preference to "genetic stratigraphy"

(Galloway1989) and "allostratigraphy" (NACSN

1983, Salvador 1987, Walker

1990, Blum1993, Mutti et al 1994).

Sequencestratigraphy and genetic stratigraphy differ primarily in the waythat

fundamentaldepositional units are defined (Figure 1). In the case of sequence

stratigraphy, the depositional sequenceis defined as a relatively conformable

succession of genetically related strata boundedby unconformities and their

correlative conformities (Mitchum1977, Van Wagoneret al 1990, ChristieBlick 1991). In the most general sense, an unconformityis a buried surface of

erosion or nondeposition.In the context of sequencestratigraphy, it has been

restricted to those surfacesthat are related (or are inferred to be related) at least

locally to the loweringof depositional base level and henceto subaerial erosion

or bypassing(Vail et al 1984, VanWagoneret al 1988). Accordingto this definition, intervals boundedby marineerosion surfaces that do not pass laterally

into subaerial discontinuities are not sequences. The fundamentalunit of genetic stratigraphy, the genetic stratigraphic sequence,is boundedby intervals

of sediment starvation (Galloway1989). Thesecorrespond approximatelywith

times of maximum

flooding and their significance is therefore quite different

fromthat of subaerial erosion surfaces.

Both kinds of sequence are recognizable in seismic reflection and borehole

data. The principal argumentfor adoptingthe genetic stratigraphic approachis

utilitarian: Intervals of sedimentstarvation are laterally persistent andpaleontologically useful. However,the boundariesof genetic stratigraphic sequencesare

�Annual Reviews

www.annualreviews.org/aronline

SEQUENCE STRATIGRAPHY

A

Genetic Stratigraphlc

455

Sequence

Set

Annu. Rev. Earth. Planet. Sci. 1995.23:451-478. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.org

by Columbia University on 09/17/05. For personal use only.

EXPLANATION

Fluvial and Coastal Plain

Shoreface and Deltaic

Shelf and Slope

Bas(nwardLimit of

AIIoetratlgraphic Unit

Submarine "Fan"

CompositeInterval of

Sediment Starvation

Depositional SequenceBoundary

B

Genetic Stratigraphic

¯ Sequence Bounclery

X

Depositional SequenceBoundary

Subaerial

Hiatus

~

DISTANCE

Figure 1 Conceptual cross sections in relation to depth (A) and geological time (B) showing

stratal geometry, the distribution of siliciclastic

facies, and competing schemes for stratigraphic

subdivision in a basin with a shelf-slope break (from NACSN

1983, Galloway 1999, Vail 1987,

Christie-Blick 199l, Vail et al 1991). Boundaries of depositional sequences are associated at

least in places with subaerial hiatuses, and they are the primary stratigraphie disec~atinuities in a

succession. Boundaries of genetic strafigraphic sequences are located within intervals of sediment

starvation, and they tend to onlap depositional sequence boundaries toward the basin margin (point

X). Allostratigraphic

units are defined and identified on the basis of bounding discontinuities.

Allostratigraphic

nomenclature is not strictly applicable where a bou~tiing unconformity passes

laterally into a conformity or where objective evidence for a stratigraphic discontinuity is lacking

(basinward of points labeled Y ).

located somewhat arbitrarily

within more-or-less continuous successions. In

somecases, no distinctive surfaces are present. In others, intervals of starvation

may contain numerous marine disconformities or hardgrounds (lithified crusts,

commordycomposed of caxbonate). Objective identification

of the maximum

flooding surface is usually difficult, and so genetic stratigraphy is especially

limited in high-resolution subsurface and outcrop studies. Unduefocus on intervals of starvation also makesit possible to ignore the presence of prominent

unconformities and to conclude (perhaps incorrectly) that sedimentary cyclicity

is due primarily to variations in sediment supply (Galloway 1989), when the

very existence of subaerial unconformities probably requires some additional

mechanism (Christie-Blick

1991). The sequence stratigraphic

approach can

�Annual Reviews

www.annualreviews.org/aronline

Annu. Rev. Earth. Planet. Sci. 1995.23:451-478. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.org

by Columbia University on 09/17/05. For personal use only.

456

CHRISTIE-BLICK& DRISCOLL

also be problematic: The boundaries of depositional sequences tend to be of

variable character, subject to modificationduring transgression, and difficult to

recognize once they pass laterally into fully marinesuccessions. Yet sequence

stratigraphy is preferable to genetic stratigraphy becausein manysettings sequence boundariesrelated to subaerial erosion are the primary stratigraphic

discontinuities and therefore the key to stratigraphic interpretation (Figure 1B;

Posamentier & James 1993).

Allostratigraphy differs from sequencestratigraphy and genetic stratigraphy

by taking a more descriptive approach to physical stratigraphy (NACSN

1983,

Salvador 1987, Walker 1990, Blum1993, Mutti et al 1994). As formalized

in the North AmericanStratigraphic Code, allostratigraphic units are defined

and identified on the basis of boundingdiscontinuities; in this respect they are

fundamentallysimilar to those of sequencestratigraphy (Figure 1). Different

terminology is justified by Walker(1990) on at least two counts. Sequence

stratigraphic concepts are regarded as imprecise, especially with respect to

scale and the meaningof such expressions as "relatively conformable" and

"genetically related." It is also arguedthat sequencestratigraphy is not universally applicable--for example, in unifacial or nonmarinesuccessions or where

uncertainty exists about the origin of a particular surface. Allostratigraphic

nomenclature

is, however,rejected here for several reasons, including historical

priority. The designations of "alloformations," "allomembers,"etc are unnecessary and overly formalistic; and these terms are not strictly applicable wherea

boundingunconformitypasses laterally into a conformity (Baum& Vail 1988)

or whereobjective evidence for a discontinuity is lacking (basinwardof points

labeled Yin Figure 1). Aswith sequencestratigraphy, allostratigraphy involves

makingjudgmentsabout the relative importanceof discontinuities (and hence

the degree of conformabilityor genetic relatedness), but it does not require an

attemptto distinguish surfaces of different origin. Nordoes this nongeneticterminologyhelp muchwheresequence stratigraphic interpretation is admittedly

difficult (for example,in deposits lacking laterally traceable discontinuities).

DEPARTURES FROM THE STANDARD MODEL

In the standard modelfor sequence stratigraphy (Figure 2), unconformityboundedsequences are composedof"parasequences" and "parasequence sets,"

whichare stratigraphic units characterized by overall upward-shoalingof depositional facies and boundedby marineflooding surfaces and their correlative

surfaces (Vail 1987; Van Wagoneret al 1988, 1990). These depositional elements are themselves assembled into "systems tracts" (Brown&Fisher 1977)

according to position within a sequenceand the mannerin whichparasequences

or parasequence sets are arranged or stacked (Posamentier et al 1988, Van

Wagoneret al 1988). Boundingunconformities are classified as type 1 or type

2 accordingto such criteria as the presenceor absenceof incised valleys, the

�Annual Reviews

www.annualreviews.org/aronline

457

Annu. Rev. Earth. Planet. Sci. 1995.23:451-478. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.org

by Columbia University on 09/17/05. For personal use only.

SEQUENCE STRATIGRAPHY

prominence of associated facies discontinuities,

and whether or not lowstand

deposits (LST in Figure 2) are present in the adjacent basin. This particular view

of stratigraphy is best suited to the study of siliciclastic

sedimentation at a differentially

subsiding passive continental margin with a well-defined shelf-slope

break, and under conditions of fluctuating

sea level. As with any sedimentary

model, it represents a distillation

of case studies and inductive reasoning, and

modifications are therefore needed for individual examples, for other depositional settings,

and as concepts evolve (Posamentier & James 1993).

Parasequences

Upward-shoalingsuccessions boundedby flooding surfaces (parasequences)

are best developedin nearshoreand shallow-marine

settings in both siliciclastic

A

I

<SMST

Ill

EXPLANATION

Fluvial andCoastalPlain

ShorefaceandDeltaic

Shelf andSlope

Submarine"Fan"

sb2

Intervalof

Sediment

Starvation

(Maximum

Flooding)

Maximum

a

iv

SubaerialHiatus

~~STbff

_~,; ...... :~ ’" : ........

,

.

¯ -DISTANCE

Figure2 Conceptualcross sections in relation to depth (A) and geological time (B) showingstratal

geometry,the distribution of silieielastie facies, and standard nomenclaturefor unconformityboundeddepositional sequences in a basin with a shelf-slope break (nmdified from Vail 1987

and Vail et ai 1991, specifically to include offlap). Systemstracts: SMST,shelf margin; HST,

Itighstand; TST, transgressive; LST,[owstand. Sequenceboundaries: sb2, type 2; sbl, type 1.

Other abbreviations: iss, interval of sedimentstarvation (condenseds~ction and maximum

flooding

surface of Vail 1987); ts, transgressive surface (top lowstandsurface and top shelf-marginsurface

of Vail et al 1991);iv, incised valley; lsw, lowstandprogadingwedge;sf, slope fma; bff, basinfloor

fan. Notethat in the seismic stratigraphie literature, the term submarine"fan" includes a range of

turbidite systemsand sediment-gravity-flewdeposits that are not necessarily fan-shaped.

�Annual Reviews

www.annualreviews.org/aronline

Annu. Rev. Earth. Planet. Sci. 1995.23:451-478. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.org

by Columbia University on 09/17/05. For personal use only.

458

CHRISTIE-BLICK

& DRISCOLL

and carbonaterocks (James1984;VanWagoner

et al 1988,1990;Swift et al

1991;Pratt et al 1992),andtheir recognitionis undoubtedly

usefulin sequence

stratigraphic analysis. However,

the tendencyfor pigeonholingin sequence

stratigraphytends to obscurerather than to illuminatethe rangeof facies arrangementsand processes involved. Sedimentarycycles vary from markedly

asymmetricalto essentially symmetrical,with the degree of asymmetry

decreasingin an offshoredirection anddepending

also on whetherparasequences

are arrangedin a foresteppingmotif (whichfavors asymmetry)

or a backstepping one. (Thetermforesteppingmeansthat each parasequence

in a succession

representsshallower-water

conditionsoverall than the parasequence

beneathit.

Backsteppingrefers to the opposite motif: overall deepeningupward.)Althoughnot strictly includedin the definitionof the termparasequence,

similar

sedimentarycycles with the samespectrumof asymmetry

are observedin many

lacustrine successions(Eugster& Hardie1975;Steel et al 1977;Olsen1986,

1990). Moreover,shoalingupwardsis not the only expressionof depositional

cyclicity(for example,

in alluvial andtidal depositsanddeep-marine

turbidites).

Objectiverecognitionof a parasequence,

as opposedto someother depositional

elementwith sharpboundaries,is thereforetenuousin nonmarine

andoffshore

marinesettings unless bounding

surfacescan be shownto correlate withmarine

floodingsurfaces.

Theconceptof parasequences

andparasequence

sets as the buildingblocksof

depositionalsequences

is also largelya matterof convention

rather thana statementabouthowsedimentsaccumulate

at different scales. Thereis clear overlap

in the lengthscales andtimescales representedby parasequences

andhigh-order

sequences (VanWagoneret al 1990, 1991; Kerans & Nance1991; Mitchum

& VanWagoner1991; Vail et al 1991; Posamentier & Chamberlain1993;

Posamentier& James1993; Sonnenfeld& Cross 1993; Christie-Blick et al

1995). The distinction betweensequencesand parasequencesis therefore

primarilya function of whether,at a particular scale of cyclicity, sequence

boundariescan or cannotbe objectivelyidentified andmapped.

Anunfortunate

by-productof the quest for sequencesand sequenceboundariesis to impose

sequence nomenclaturewhenparasequenceterminologywouldbe moreappropriate. Floodingsurfacesare sometimes

interpreted as sequenceboundaries

whenno objective evidencefor such a boundaryexists (e.g. Lindsay1987,

Prave1991,Lindsayet al 1993,Montafiez& Osleger1993)or, if a sequence

boundary

is present,it is locatedat a lowerstratigraphiclevel.

Systems Tracts

Thethreefoldsubdivisionof sequences

into systemstracts is basedon the phase

lag between

transgressive-regressive

cycles andthe development

of corresponding sequenceboundaries(Figure2B). In the standardmodelfor siliciclastic

sedimentation

with a shelf-slopebreak, regressionof the shorelinecontinues

�Annual Reviews

www.annualreviews.org/aronline

Annu. Rev. Earth. Planet. Sci. 1995.23:451-478. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.org

by Columbia University on 09/17/05. For personal use only.

SEQUENCESTRATIGRAPHY 459

after the developmentof the sequenceboundary,so that the regressive part of

any cycle of sedimentationis divisible into two systems tracts: the highstand

belowthe boundary(HSTin Figure 2) and the lowstand(or shelf margin)

tems tract above it (LSTand SMST

in Figure 2). The designation of systems

tracts has becomestandardprocedurein sequencestratigraphy as if this werean

end in itself but, as with parasequences,subjective interpretation and pigeonholing tend to obscurethe natural variability in sedimentarysystems. There is

no requirementfor individual systems tracts to have any particular thickness

or geometry,or evento be representedon a particular profile or in a particular

part of a basin (Posamentier & James1993). It is commonin deep water for

lowstandunits to be stacked, with intervening transgressive and highstandunits

representedby relatively thin intervals of sedimentstarvation. In shelf areas,

the stratigraphy tends to be composed

primarily of alternating transgressive and

highstandunits, but these vary greatly in thickness and they are not necessarily

easy to distinguish. Still farther landward,highstandsmaybe stacked with no

other systemstracts intervening, a situation that is likely to challenge those

intent on assigning systems tract nomenclaturein nonmarinesuccessions.

The most troublesom, e systems tract is the lowstand, which according to

the original definition of the term represents sedimentationabovea sequence

boundaryprior to the onset of renewedregional transgression (Figure 2).

is characterized by remarkablyvaried facies and in manycases by a complex

internal stratigraphy that in deep-marineexamplescontinuesto be the subject of

vigorous debate (Weimer1989, Normarket al 1993). The lowstandis also the

one element of a depositional sequencethat separates it from a transgressiveregressive cycle (e.g. Johnsonet a11985,Embry1988),It is perhapsnatural that

sequencestratigraphers have attemptedto identify lowstandunits, even where

the presence of such deposits is doubtful (for example, manyshelf and ramp

settings), becausethis helpsto deflect the criticism that sequencestratigraphyoffers nothing morethan newterminologyfor long-established concepts. In shelf

and rampsettings, the term lowstandis routinely applied to any coarse-grained

and/or nonmarinedeposit directly overlying a sequence boundary, especially

wheresuch deposits are restricted to an incised valley (e.g. Baum&Vail 1988,

VanWagoneret al 1991, Southgate et al 1993). However,sedimentological and

paleontological evidencefor estuarine sedimentationwithin (fluvially incised)

valleys (e.g. Hettinger et al 1993)in manycases precludesthe lowstandinterpretation, because such estuaries develop as a consequenceof transgression.

JC Van Wagoner(personal communication,1991) has defended the use of the

term lowstandfor estuarine valley fills on the groundsthat the differentiation

of sandstones within incised valleys from those of the underlying highstand

systemstract is of practical importancefor the delineation of reservoirs for oil

and gas. However,such commercialobjectives can surely be achieved without

fundamentallyaltering the systemstract concept.

�Annual Reviews

www.annualreviews.org/aronline

460

CHRISTIE-BLICK& DRISCOLL

Annu. Rev. Earth. Planet. Sci. 1995.23:451-478. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.org

by Columbia University on 09/17/05. For personal use only.

Variations in SequenceArchitecture

Case studies in a great variety of settings have led to attempts to develop

modified versions of the standard sequencestratigraphic model. Examplesinclude settings wheresedimentationis accompaniedby growthfaulting, terraced

shelves and siliciclastic ramps, carbonateplatforms and ramps,nonmarineenvironments(fluvial, eolian, and lacustrine), and environmentsproximalto large

ice sheets (Vail 1987; Sarg 1988; Van Wagoneret al 1988, 1990; Boulton

1990; Olsen 1990; Vail et al 1991; Greenlee et al 1992; Posamentier et al

1992a; Walker &Plint 1992; Dam& Surlyk 1993; Handford & Loucks 1993;

Kocurek & Havholm1993; Schlager et al 1994; Shanley & McCabe1994).

Attempts have also been madeto integrate geological studies in outcrop and

the subsurface with seismic profiling and shallow sampling of modernshelves

and estuaries (Demarest & Kraft 1987; Suter et al 1987; Boyd et al 1989;

Tessonet al 1990, 1993; Allen &Posamentier 1993, Chiocci 1994), flume experiments(Woodet al 1993, Kosset al 1994) and small-scale natural analogues

(Posamentier et al 1992b), and computersimulations (Jervey 1988, HellandHansenet al 1988, Lawrenceet al 1990, Ross 1990, Reynolds et al 1991,

Steckler et al 1993, Bosenceet al 1994, Ross et al 1994). The main emphasis

of these studies has been to documentvariations in the arrangementof facies

and associated stratal geometry,but amongthe moreinteresting results has been

the emergenceof somenewideas about the origin of sequence boundaries and

other stratigraphic discontinuities.

ORIGIN OF SEQUENCEBOUNDARIES

The conventional interpretation of sequenceboundariesis that they are due to

a relative fall of sea level (Posamentieret al 1988, Posamentier&Vail 1988,

Sarg 1988, Vail et al 1991). For example,a boundarymight be said to develop

whenthe rate of relative sea-level fall is a maximum

or whenrelative sea level

begins to fall at somespecified break in slope, thereby initiating the incision

of valleys by headwarderosion. The concept of relative sea-level change accounts qualitatively for the roles of both subsidenceand eustasy in controlling

the space available for sediments to accumulate.However,existing modelsare

fundamentallyeustatic because it is invariably the eustatic componentthat is

inferred to fluctuate; the rate of subsidenceis assumedto vary only slowly, if at

all. Here wedrawattention to several waysin whichthe conventionalexplanation of sequenceboundariesneeds to be modified, particularly in tectonically

active basins.

Gradual vs Instantaneous Developmentof Sequence Boundaries

It is widely assumedthat sequence boundaries develop more or less instantaneously(Posamentieret al 1988, Vail et al 1991). Themainevidencefor this

�Annual Reviews

www.annualreviews.org/aronline

Annu. Rev. Earth. Planet. Sci. 1995.23:451-478. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.org

by Columbia University on 09/17/05. For personal use only.

SEQUENCESTRATIGRAPHY 461

the markedasymmetryof depositional sequences, which in seismic reflection

profiles are characterized by progressive onlap at the base and by a downward

(or basinward)shift in onlapat the top (Figure 2; Vail etal 1977, 1984;Haqet

1987). (Theterm onlap refers to the lateral terminationof strata against an underlying surface.) Abruptdownward

shifts in onlap are taken to imply rates of

relative sea-level changesignificantly higher than typical rates of subsidence,

and that the sea-level change must therefore be due to eustasy, presumably

glacial-eustasy (Vail et al 1991).

Whileit is undoubtedlytrue that glacial-eustasy has played an important

role in modUlatingpatterns of sedimentationsince Oligocenetime (Bartek et al

1991, Miller et al 1991), and probably during other glacial intervals in earth

history, such explanationsare not plausible for periods such as the Cretaceous

for whichthere is very little evidencefor glaciation (Frakes et al 1992). Nor

are such explanatioiis required by available stratigraphic data. In manycases,

the highstand systemstract is divisible into twoparts: a lower/landwardpart

characterized by onlap and sigmoidclinoforms(clinoforms are inclined stratal

surfaces associated with progradation), and an upper/seawardpart characterized by offlap and oblique clinoforms (Figure 2; Christie-Blick 1991). Offlap

(the upwardterminationof strata against an overlying surface) is not likely

be due solely to the erosional truncation of originally sigmoidclinoforms, The

progressive onlap implied by this interpretation is not possible during a time

of increasingly rapid progradation without a markedincrease in the sediment

supply. Moreover,the inferred erosion is unlikely to havetaken place in the subaerial environmentbecausesubaerial erosion tends to be focused within incised

valleys, and the amountof erosion required in manycases exceeds what can

reasonably be attributed to shoreface ravinementduring transgression. A more

reasonable interpretation is that offlap is due fundamentallyto bypassingduring progradation (toplap of Mitchum1977), implyingthat sequenceboundaries

developgradually over a finite interval of geologic time (Christie-Blick 1991).

Supportfor this idea is providedby recent high-resolution sequencestratigraphic studies in outcrop. A remarkable series of forestepping high-order

sequences is exposedin the upper part of the San Andres Formation, a carbonate platform of Permian age in the GuadalupeMountainsof southeastern

NewMexico (Figure 3A; Sonnenfeld & Cross 1993). Individual high-order

sequencesconsist of two half-cycles. Thelowerhalf-cycle (primarily transgressive) is predominantlysiliciclastic and onlaps the underlying sequenceboundary. The upper half-cycle (regressive) is composedmainly of carbonate rocks

and is characterized by onlap and downlap(downward

termination of strata)

the base and in someinstances by offlap at the top. Thesehigh-order sequences

are themselves oblique to a prominentlow-order sequenceboundaryat the top

of the San AndresFormation (top of sequences uSA4and uSA5). On the basis

of karstification, this surface is interpreted by Sonnenfeld&Cross (1993)

�Annual Reviews

www.annualreviews.org/aronline

Annu. Rev. Earth. Planet. Sci. 1995.23:451-478. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.org

by Columbia University on 09/17/05. For personal use only.

462

CHRISTIE-BLICK& DRISCOLL

have been exposedsubaerially. At the resolution of conventional seismic data,

only the low-order sequence boundaries in the San Andres Formation would

be identified (Figure 3B) and the oblique truncation of high-order sequences

wouldbe interpreted as offlap (cf figure 11 of Brinket al 1993). However,the

siliciclastic half-cycles of the high-ordersequencesindicate that the platform

was bypassed episodically during overall progradation. The sequence boundary at the top of the San Andreswas therefore not producedby an instantaneous

downward

shift in onlap but is instead a compositesurface.

Anotherpertinent exampleof high-resolution sequencestratigraphy is drawn

from the work of Van Wagonerand colleagues in a late Cretaceous forelandbasin ramp setting in the BookCliffs of eastern Utah and western Colorado

(Van Wagoneret al 1990, 1991). Numeroussequence boundaries have been

documentedin the strongly progradational succession betweenthe Star Point

Formation and Castlegate Sandstone (Figure 4A). Twoof the most prominent

boundaries are present at the level of the Desert Memberof the Blackhawk

Formationand Castlegate Sandstone (Figure 5). Theseboundaries are characterized by valleys as muchas several tens of meters deepincised into underlying

A

~

SA4/5

EXPLANATION

~

.......

~

300m

Sequence Boundary

High-OrderSequenceBoundary

Other Stratal Surfaces

Stratal Termination

SedimentDepositedAbove

~

Storm WaveBase

Sediment

Deposited

[~ Storm Wave Base

B

Approx. Location

of Detail

~

_,, ,~,~

o e Sa

des

100

Below

1 m

.....

5 km

==,,,

~---------Cutoff~~

uSA3

Grayburg

ne;o~n

~

Brushy

~Canyon

Figure3 (A) Simplified

stratigraphiccrosssectionof the upperpart of SanAndres

Formation

(Permian)

in the Guadalupe

Mountains,

New

Mexico.

(B)Schematic

representation

of the broader

stratigraphic

contextof theSanAndres

Formation

at the scaleof conventional

seismicreflection

data. Individualhigh-ordersequences

withinsequences

uSA4(numbered

1-12)anduSA5

(numbered13-14)are characterized

bystratal onlapandofflapandare themselves

obliqueto a still

lower-order

sequenceboundary

at the top of the SanAndresFormation.

Thedatumfor cross

sectionAis the baseof the Hayes

sandstone

oftbeGrayburg

Formation.

Alsoshown

in Bare the

names

of otherassociated

lithostratigraphic

units. (Modified

fromSonnenfeld

&Cross1993.)

�Annual Reviews

www.annualreviews.org/aronline

SEQUENCE STRATIGRAPHY

463

A

Thistle

Price

~1

~

Sunnyside GreenRiver

I

I

I

~/~.NorthHorn(Part)

..........

Annu. Rev. Earth. Planet. Sci. 1995.23:451-478. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.org

by Columbia University on 09/17/05. For personal use only.

~

BTurkeyCreek

S

Palisade

L

~///~T~$dl~r,

1

FarroW’,

~l~sien

~~’~ ~ ........

~xX~~--~

&~~~esed

oe

~ ..~o

~~

~~

and

UtahI Colo.

,,

_

~_.

Mbr

Blac~awk

~

Op~

Marine

~ ~asp ~ Forelapd- ~ Ll~oral

Deltal

50 km Fort Collins

Mowry Shale

(~

Skull Creek...........

.........

Plalnview,~

:’ ......... ’ "

CastlegateSandstone

o~

~

Fm.

.

Shelf

...................

~

LowerCoastalPlain

andIncisedValley Fill

UpperCoastalPlain

~

Piedmont

~

~

Mostly Nonmarine

~

......

--

Sequence Boundary

Max. Flooding Surface

Other Stratal Surface

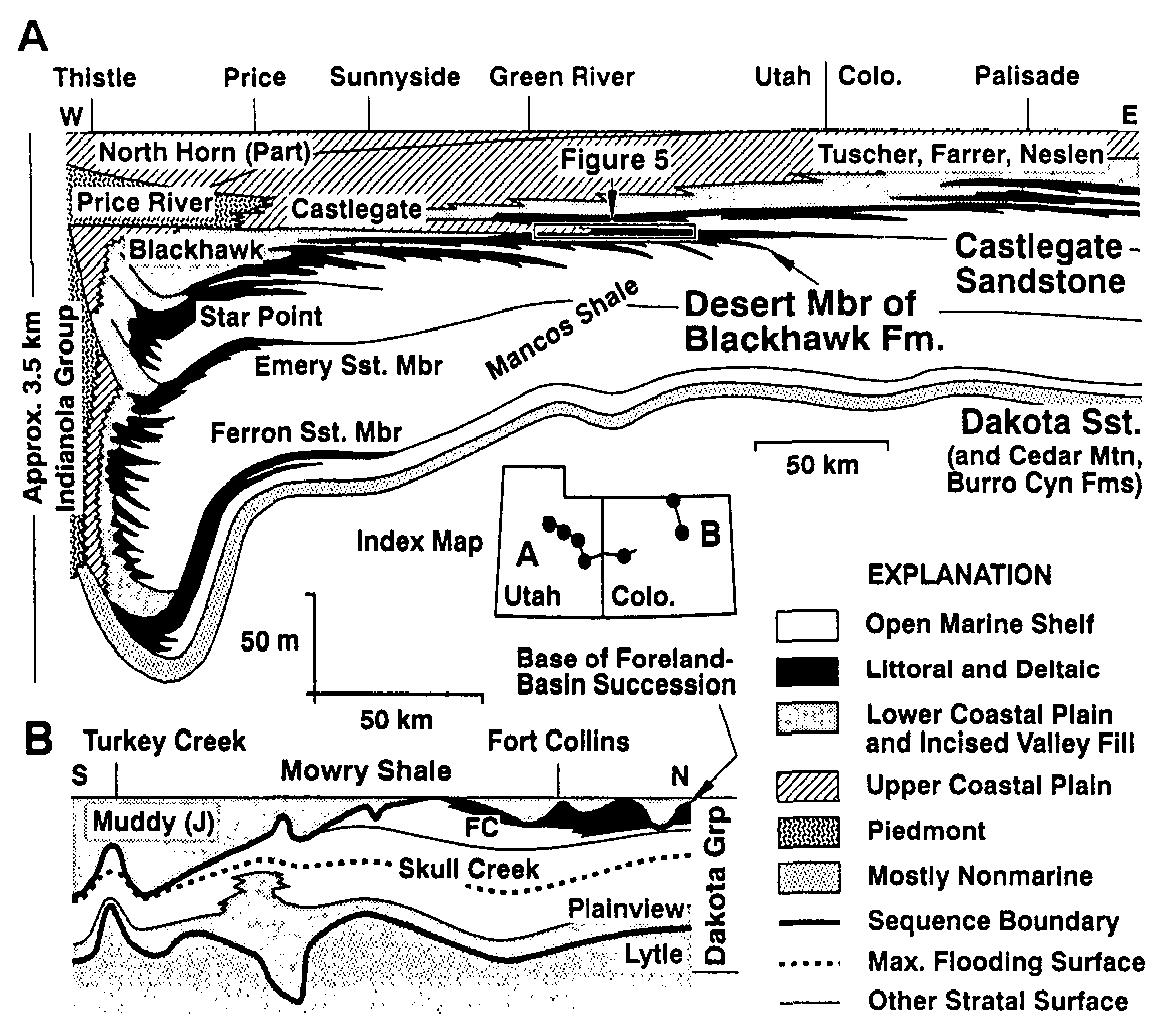

Figure4 Simplifiedstratigraphiccross section andlithostratigraphic nomenclature

for mid-to

upperCretaceousstrata in the BookCliffs, eastern UtahandwesternColorado(A; fromNummedal

&Remy

1989),witha detail of the Albiansequencestratigraphy(DakotaGroup)of noah-central

Colorado(B; fromWeimer

1984and RJ Weimer,personal communication,

1988). A detail of the

DesertMember

of the Blackhawk

FormationandCastlegate Sandstone(box in A) is illustrated

in Figure5. Thebaseof the foreland-basinsuccessionis markedapproximately

by a regional

sequenceboundary

ai or near the base of the DakotaSandstone(in A) andat or near the base

the Muddy

(or J) Sandstoneof the DakotaGroup(in B). FCrefers to the Fort Collins Member,

portionof the Muddy

Sandstone

that locally underliesthe sequenceboundary.

littoral sandstones,by the offlap of successiveparasequences,

andby a marked

basinwardshift of facies. In the conventionalinterpretation, the incision of

valleys by headward erosion from a break in slope near the shoreline ought to

deliver a significant volume of sediment tothe adjacent shelf, and prominent

lowstand sandstones would be expected (Van Wagoner et al 1988, 1990). Instead, each sequence boundary passes laterally into a marine flooding surface

and eventually into the MancosShale (Figure 4A) with little or no evidence for

lowstand deposits as this term is defined above.1 Our solution to this apparent

paradox is that the valleys were not incised as a result of headward erosion.

ID Nummedal

(personal communication,

1994)has recently identified a possible lowstand

depositbasinward

of the Castlegatelowstandshorelineonthe basis of well-loginterpretation.The

depositis perhapsanalogous

to the relativelythin lowstandunits fromthe Albertabasindescribed

byPlint (1988,1991)andPosamentier

et al (1992a).

�Annual Reviews

www.annualreviews.org/aronline

464

CHRISTIE-BLICK & DRISCOLL

Annu. Rev. Earth. Planet. Sci. 1995.23:451-478. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.org

by Columbia University on 09/17/05. For personal use only.

A consequence of the idea that sequence boundaries develop gradually during

highstand progradation is that incised valleys at the Desert and Castlegate sequence boundaries initially propagated downstream, and that most of the eroded

sediment accumulated at the highstand shorelines.

If sequence boundaries do not after all develop instantaneously, it is not

necessary to call upon rapid eustatic change for which there is no plausible

mechanism during nonglacial times. Forward modeling indicates that sequence

West

Thompson ’ Thompson

Pass

Canyon

Tusher

Canyon

W

Sagers

Canyon

East

Bull

Canyon

Strychnine

Wash

Flooding Surface

at baseof

Buck Tongue

SF/E

Castlegate

Sequence

OT

OT

SequenceBoundary

PassesLaterally

into FloodingSurface

LSF

OT

20 m

OT

f

10

\

~

~-~

DesertSequence

Boundary

o

~

~

W

m

Marine

Shale

Littoral Sandstone

Shale

Coal

EXPLANATION

......

Max.~:loodlng Surface

OtherStratal Surface

Para,llel Lamination

Current Ripples

~

Estuarine~--Cross-stratification

Sandstone

~

conglomerate

~ cross.stratification

Figure 5 Stratigraphic cross section of the Desert Member

of the Blackhawk

Formationand

Castlegate Sandstoneshowingdepositional facies andsequencegeometry(simplified fromVan

Wagoneret al 199l, Nummedal

&Cole 1994). See Figure 4 for location. The two sequence

boundariesillustrated are characterizedup-dip (west)by well-developed

incisedvalleys.TheDesert

sequenceboundary

passesdown-dip

(eastward)in the vicinity of SagersCanyon

into a marineflooding surfacethat wasprobablymodifiedby ravinement

duringtransgression.Asimilartransition is

observedin the CastlegateSandstone

as it is tracedfarther eastward.Notethe presenceof offlappingparasequences

beneatheachsequenceboundary.Abbreviationsfor generalizedpaleoenvironmerits:BF,braidedfluvial; SF/E,sinuousfluvial/estuarine;FS, foreshore;USF,uppershoreface;

LSF,lowershoreface;OT,offshoretransition. Systems

tracts (modifiedfromthe interpretationsof

VanWagoner

et al 1991and Nummedal

&Cole 1994): HST,highstand; TST,transgressive. Some

uncertaintyexists aboutthe locationof the interval of maximum

floodingin the Desertsequence

owing to the difficultyof interpretingparasequence

stackingtrendsin thin sections:It is at or slightly

abovethe dashedline labeled RavinementSurface(D Nummedal,

personal communication,

1994).

�Annual Reviews

www.annualreviews.org/aronline

SEQUENCESTRATIGRAPHY 465

Annu. Rev. Earth. Planet. Sci. 1995.23:451-478. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.org

by Columbia University on 09/17/05. For personal use only.

boundaries can be produced by eustatic fluctuations at rates comparableto

typical rates of tectonic subsidenceand that they do so by gradual basinward

expansionand subsequentburial of zones of bypassingand/or erosion (ChristieBlick 1991, Steckler et al 1993). Consequently,if the rate of eustatic change

required to generate a sequenceboundaryis small, there is no reason to assume

that sequenceboundariesare necessarily due to eustatic change.

Tectonically

Active Basins

In the light of these considerations, howdo sequence boundaries develop in

tectonically active settings such as extensional,foreland, and strike-slip basins?

Oneview, whichis almost certainly incorrect, is that the local developmentof

sequenceboundariesin such basins maybe entirely tectonic in origin (Underhill

1991). Anotherview is that tectonic processes control long-term patterns of

subsidenceand that short-term depositional cyclicity is due to eustatic change

(e.g. Vail et al 1991, Devlin et al 1993, Lindsayet al 1993). Again, this

an assumptionthat in manycases is probably not warrantedfor times in earth

history whenrates of eustatic change were comparableto rates of tectonic

subsidence (e.g. Cretaceous). Sequenceboundaries are not merelyenhanced

obscuredby tectonic activity (cf Vail et al 1984, 1991). Boththeir timing and

their very existence are due to the combinedeffects of eustasy and variations

in patterns of subsidence/uplift and sedimentsupply. The roles of these factors

and the mannerin whichthey interact are admittedlyvery difficult to sort out,

but recent studies provide someuseful first-order clues.

Animportantattribute of tectonically active basinsis that it is possiblefor the

rate of tectonic subsidenceto increase and decrease simultaneouslyin different

parts of the samebasin (Figure 6). Sequenceboundariesthat are fundamentally

of tectonic rather than eustatic origin cannotthereforebe attributed satisfactorily

to the conceptof a relative sea-levelfall or evenan increasein the rate of relative

sea-level fall, becauserelative sea-level mayhavebeenboth rising and falling

at an increasingrate in different places.

In this regard, patterns of subsidenceand uplift in foreland and extensional

basins are actually very similar during times of active deformationas well as

quiescence(Christie-Blick &Driscoll 1994). In the case of a foreland basin,

loading by the adjacent orogenleads to regional subsidenceand to uplift in

the vicinity of the peripheral bulge, with a wavelengthand amplitudethat are

governedby the flexural rigidity of the lithosphere (Figure 6A; Beaumont

1981,

Karner &Watts 1983). Uplift mayalso occur locally at the proximal margin

of the basin as a result of the propagationof thrust faults at depth. Similarly,in

extensional basins, subsidenceand tilting of the hanging-wallblock (abovethe

fault in Figure 6) are accompaniedby uplift of the footwall (belowthe fault;

Wernicke &Axen 1988, Weissel & Karner 1989). During times of tectonic

quiescence, these patterns are reversed, although the amplitudesare small in

�Annual Reviews

www.annualreviews.org/aronline

466

CHRISTIE-BLICK& DRISCOLL

A

ACTIVE DEFORMATION

Foreland basin

j ~ ~

B

QUIESCENCE

Foreland basin

PeripheralBulge

Annu. Rev. Earth. Planet. Sci. 1995.23:451-478. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.org

by Columbia University on 09/17/05. For personal use only.

Thrusting

Extensional basin

NormalFaulting

~ Footwall

Extensionalbasin

EXPLANATION

Hanging Wall

[~ Sediment

Thermal

Subsidence

NNNNWater

Figure 6 Schematicdiagrams comparingpatterns of uplift and subsidence in foreland and extensional basins during times of active deformation(A) and quiescence(B). See text for discussion.

comparisonwith the deflections engenderedby active deformation(Figure 6B;

Heller et al 1988, Jordan & Flemings 1991). Erosional unloading leads to

regional rebound of the orogen and adjacent depocenter and to depression

of the peripheral bulge. At the same time, the accumulationof terrigenous

sedimentderived fromthe orogenresults in additional subsidenceat the distal

side of the basin and to lateral migrationof the peripheral bulge awayfrom the

orogen (Jordan &Flemings1991). A similar pattern of uplift and subsidence

mayarise during times of tectonic quiescencein extensional basins, through a

combinationof erosional unloadingof the footwall block and thermally driven

subsidence,especially whenthe latter is offset fromthe original depocenter(as

illustrated in Figure,6B).

Morecomplicated scenarios can also be envisaged. For example, foreland

basins are commonlysegmentedby block-faulting, and lithospheric extension

maybe accommodated

by a series of tilted fault blocks or distributed inhomogeneously

as a function of depth and lateral position within the lithosphere.

Subsidenceand uplift mayalso be complicatedin three dimensionsby the presence of salients in the orogenor of accommodation

zones in extensional basins.

Patterns of subsidenceand uplift in strike-slip basins tend to be evenmorecomplicated and subject to markedchanges on short time scales (Christie-Blick

Biddle 1985).

The developmentand characteristics of sequenceboundaries in tectonically

active basins are directly related to patterns of subsidenceand uplift of the

sort outlined here and to the fact that the patterns vary betweentimes of active deformation and quiescence. At a regional scale, the progradation of

�Annual Reviews

www.annualreviews.org/aronline

Annu. Rev. Earth. Planet. Sci. 1995.23:451-478. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.org

by Columbia University on 09/17/05. For personal use only.

SEQUENCESTRATIGRAPHY 467

sedimentary systems, the filling of available accommodation

with sediment,

the loweringof depositional base level, and the incision of valleys are favored

duringtimes of tectonic quiescence(e.g. Heller et al 1988).In contrast, active

deformationis associated with regional subsidence and tilting, flooding and

backsteppingof sedimentarysystems, an increase in topographicrelief along

the faulted basin margins, and a narrowingof the depocenter(e.g. Underhill

1991). In both foreland and extensional basins, the most prominentsequence

boundariestherefore are expected to correspondwith the onset of deformation.

Theseboundariesconsist of subaerial exposuresurfaces that pass laterally into

marine onlap/downlapsurfaces of regional extent (Jordan &Flemings 1991,

Underhill 1991, Driscoll 1992, Christie-Blick &Driscoll 1994, Driscoll et al

1995). In contrast to the standard model, the formationof a sequenceboundary

is not necessarily associatedwith a basinwardshift in facies, and wherepresent,

such facies shifts maybe restricted to areas that weresubaerially exposed.The

developmentof topographic relief mayin somecases lead to the accumulation of thick successions of turbidites in deep water. However,contrary to the

conventionalinterpretation, these deposits are not strictly "lowstands"if they

accumulateduring a time of regional flooding [see Southgate et al (1993) and

Holmes&Christie-Blick (1993) for a possible examplefrom the Devonian

the Canningbasin, Australia].

Several of these points can be illustrated with reference to the late Cretaceous foreland basin of Utah and Colorado (Figure 4). The base of the

foreland-basin succession in eastern Utah and Coloradocorresponds approximately with a regional sequence boundaryat or near the base of the Dakota

Sandstone(Figure 4A) and at or near the base of the Muddy(or J) Sandstone

of the DakotaGroup(Figure 4B). The succession abovethis surface is characterized by a markedincrease in the rate of sediment accumulationand by an

abrupt transition from nonmarineto relatively deep marinesedimentaryrocks

(Mancos/Mowry

Shale; Heller et al 1986, Vail et al 1991). These features are

fundamentallyattributable to the onset in late Albiantime of a phaseof crustal

deformationand accelerated subsidence; the contribution of eustatic change

is indeterminate but is presumedto have been small. Wedo not preclude the

possibility of slightly earlier (late Aptianto Albian, pre-Dakota)foreland-basin

developmentto the west (Yingling &Heller 1992), but the strata are entirely

nonmarineand the evidence is equivocal. Within the foreland-basin succession, the origin of other sequenceboundariesis less firmly established, but

the BlackhawkFormation and Castlegate Sandstoneexhibit features that are

consistent with our model. The Blackhawkand lower/distal part of the Castlegate (belowthe Castlegate sequence boundary; Figure 5) are characterized

strong progradation and the developmentof offlap, consistent with erosional

unloading of the orogenduring a time of tectonic quiescence (cf Posamentier

& Allen 1993). The upper/proximalpart of the Castlegate (above the sequence

�Annual Reviews

www.annualreviews.org/aronline

Annu. Rev. Earth. Planet. Sci. 1995.23:451-478. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.org

by Columbia University on 09/17/05. For personal use only.

468

CHRISTIE-BLICK& DRISCOLL

boundary)is transgressive and, as datumedfroma floodingsurface at the base of

the BuckTongueof the MancosShale, it thickens towardsthe orogen(Figure 5).

At a regional scale, it appears to pass laterally into syn-orogenicconglomerate

(Price River Formation) and to overstep the BlackhawkFormation, which was

uplifted and bevelled to the west (Figure 4). Thesefeatures makeit hard to argue that the Castlegate sequence boundarydevelopedsolely or even primarily

as a result of eustatic change.

A seismic exampleof sequence developmentrelated to episodic block faulting in an extensional setting is providedby a seismic reflection profile (line

NF-79-108)from the Jeanne d’Arc basin of offshore eastern Canada(Figure 7).

The basin records a series of extensional events betweenlate Triassic and early

Cretaceous time (Jansa &Wade1975, Tankard et al 1989, McAlpine1991);

Figure 7 illustrates the last of these prior to the onset in late Aptiantime of

seafloor spreading betweenthe GrandBanks of Newfoundlandand the Iberian

peninsula. Reflections below the late Barremian unconformity are approximately parallel and concordantwith the unconformity.Abovethis surface, the

onlap of reflections and their divergencetowards the border fault documentthe

onset of crustal extension. Similar reflection geometryis evident at the early

Aptian and late Aptian unconformities, although reflections are approximately

parallel abovethe latter. This is taken to indicate that extensionhad ceased by

late Aptian time (Driscoll 1992, Driscoll et al 1995). Evidencefromavailable

core indicates that the onlap surfaces are associated with upwarddeepening

of depositional facies, but the surfaces are interpreted as sequenceboundaries

becausethey are inferred to pass laterally into subaerial exposuresurfaces. The

observedgeometryrequires rifting betweenlate Barremianand late Aptiantime.

Our preferred interpretation is that each of the mappedsequence boundaries

records times of accelerated block tilting. Analternative interpretation, that

the early and late Aptian boundariesare due primarily to eustatic fluctuations

duringa time of moreor less continuousblocktilting, is not consistelat with the

absence of anticipated lowstanddeposits in closed paleobathymetriclows (for

example,at the MercuryK-76 well, Figure 7).

Role of In-Plane Force Variations

Sequence Boundaries

in the Origin of High-Order

Oneof the mainargumentsfor interpreting high-order depositional sequences

in terms of eustatic changeis the absence of another suitable mechanism.We

have seen in the Jeanne d’Arc basin examplethat episodic tilting mayprovide

such a mechanism

in extensional basins. However,difficulties arise in foreland

basins because,in such settings, subsidenceis driven primarily by the integrated

vertical load of the orogen. This can changeonly slowly through a combination

of internal deformation,the propagationof thrust faults into the syn-orogenic

sediments, and the erosion of topography(Sinclair et al 1991).

�Annual Reviews

www.annualreviews.org/aronline

Annu. Rev. Earth. Planet. Sci. 1995.23:451-478. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.org

by Columbia University on 09/17/05. For personal use only.

SEQUENCESTRATIGRAPHY 469

An imaginative and somewhatcontroversial solution to this dilemmahas

emergedfrom the recognition and modelingof in-plane force variations in

the lithosphere (Lambeck1983, Cloetingh et al 1985, Karner 1986, Braun

&Beaumont1989, Karner et al 1993). The best evidence for the existence

of such forces is the incidence of intraplate earthquakes (e.g. Lambeck

et al

1984, Bergman&Solomon1985). Changes in in-plane force are thought to

result from changesin the plate-boundaryforces associated with, for example,

ridge-push, slab-pull, and collisional tectonics (Sykes &Sbar 1973, Cloetingh

&Wortel 1985, Zobacket al 1989). Althoughuncertainty exists about both

the magnitudeof the forces and the time scale over which they might vary,

it is not unreasonable to think that such forces maybe relevant to the developmentof somesequence boundaries. The response of the lithosphere to

in-plane compressionconsists of two components,one elastic (flexural) and

the other inelastic (brittle; Goetze &Evans 1979, Karner et al 1993). The

brittle component,whichis associated with deformationin the upper part of

the lithosphere, is influenced by the preexisting structure of the crust and the

orientation of faults with respect to the applied tectonic force. It includes the

well-knownphenomenon

of extensional basin inversion. The flexural response

to in-plane compressiondependson the shape of any preexisting deflection of

the lithosphere, the amplitudeof the applied force, and the flexural strength of

the lithosphere at the time the force wasapplied. In the case of foreland basins,

the predicted flexural response to compressionconsists of enhancedsubsidence

in the depocenter,uplift of the peripheral bulge, and a reductionin the flexural

wavelength. The amplitude of subsidence and uplift producedin this wayare

approximatelythe same because the wavelengthsof features being selectively

modified are approximatelyequal (Karner et al 1993). The predicted flexural

responsefor extensional basins is quite different. In-plane compressionresults

in uplift of the depocenterand increased subsidenceof the basin margins. Inplane tension leads to uplift of the basin marginsand to enhancedsubsidenceof

the depocenter (Braun & Beaumont1989, Karner et al 1993). The amplitude

and wavelengthof the flexural deformationare a strong function of the extensional basin geometryand, in the case of basins undergoingpost-rift thermal

subsidence, of the spatial relationship betweenrift basins and any associated

passive continental margin.

In view of these considerations, our concepts of active deformation and

tectonic quiescence need to be modified. With respect to this second-order

effect, panels that in Figure 6 are labeled "active deformation"include times

of increased in-plane compressionin the foreland basin exampleand decreased

in-plane compression(increased tension) in the extensional basin example.

Owingto the relatively short length scales relevant to extensional basins (tens

of kilometers), it is anticipated that the stratigraphy of such basins oughtto be

influencedstronglyevenat short timescales by episodicblock tilting (the brittle

�Annu. Rev. Earth. Planet. Sci. 1995.23:451-478. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.org

by Columbia University on 09/17/05. For personal use only.

CHRISTIE-BLICK & DRISCOLL

Annual Reviews

www.annualreviews.org/aronline

470

E

m

0

u-

?

W

Y

h

b

IL

z

aJ

.-C

-I

�Annu. Rev. Earth. Planet. Sci. 1995.23:451-478. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.org

by Columbia University on 09/17/05. For personal use only.

Annual Reviews

www.annualreviews.org/aronline

: Ill/I II

SEQUENCE STRATIGRAPHY

471

�Annual Reviews

www.annualreviews.org/aronline

Annu. Rev. Earth. Planet. Sci. 1995.23:451-478. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.org

by Columbia University on 09/17/05. For personal use only.

472

CHRISTIE-BLICK& DRISCOLL

componentof the deformation). In contrast, because the integrated vertical

load of an orogen changesonly slowly (millions to tens of millions of years;

Sinclair et al 1991), the stratigraphy of foreland basins oughtto be muchmore

sensitive on short time scales to the flexural effects of changesin in-plane compression, providing that the forces involvedare sufficiently large. A possible

test of this idea is to comparethe stratal geometryof sequencesof different

scale in the samebasin. If high-order sequencesare due to eustatic change, as

manyhave inferred (e.g. Posamentier &Allen 1993), their geometryought

reflect overall patterns of subsidence.If they are instead a result of changesin

in-plane compression,high-order transgressive systems tracts ought to thicken

preferentially towardthe orogenrelative to associated highstandunits (as appears to be the case in the Castlegate example), and backstepping sequences

ought to thicken toward the orogen relative to forestepping sequences. The

complicationsassociated with lateral changesin facies, compaction,and water

depth can be reduced by studying transects parallel to shorelines across foreland basins with axial drainage (for example, the DunveganFormation of the

Alberta basin; Plint 1994).

CONCLUSIONS

Sequencestratigraphy is concernedwith the analysis of sedimentsand sedimentary rocks with reference to the mannerin whichthey accumulatelayer by layer.

Asa practical techniqueand in spite of existing terminology,it requires no assumptionsabout eustasy. Oneof the principal frontiers of the discipline is an

effort to developan understandingof the manyinterrelated factors that govern

sedimenttransport and accumulationin a great range of depositional settings

and environments. The conventional interpretation of sequence boundaries is

that they are due to a relative fall of sea level and that they developmoreor

less instantaneously. In this paper we argue that in manycases such boundaries

form gradually over a finite interval of geologic time. The widely employed

concept of relative sea-level change provides few insights into howsequence

boundariesactually develop, especially in tectonically active basins.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This paper is an outgrowth of more than a decade of research in sequence

stratigraphy in a widevariety of depositional and tectonic settings. Weare indebted to numerouscolleagues for stimulating discussions of the issues, and we

thank MSteckler and L Sohl for reviewing the manuscript. Weacknowledge

support from the National Science Foundation (Earth Sciences and OceanSciences); Office of NavalResearch; the Donorsof the PetroleumResearch Fund,

administered by the American Chemical Society; and the Arthur D Storke

MemorialFund of the Departmentof Geological Sciences, ColumbiaUniversity. This paper is Lamont-Doherty

Earth Observatory Contribution No. 5257.

�Annual Reviews

www.annualreviews.org/aronline

SEQUENCE STRATIGRAPHY

473

AnyAnnual.Review

chapter,as well as anyarticle cited in an AnnualReviewchapter,

maybe purchasedfromthe Annual

ReviewsPreprintsandReprintsservice.

1-800-347.8007;415-259-5017;emaiharpr@class.org

Annu. Rev. Earth. Planet. Sci. 1995.23:451-478. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.org

by Columbia University on 09/17/05. For personal use only.

Literature Cited

Allen GP, Posamentier HW.1993. Sequence

stratigraphy and facies modelof an incised

valley fill: the GirondeEstuary, France. J.

Sediment. Petrol. 63:378-91

Bartek LR, Vail PR, Anderson JB, EmmetPA,

Wu S. 1991. Effect of Cenozoic ice sheet

fluctuations in Antarcticaon the stratigraphic

signature of the Neogene.J. Geophys.Res.

96:6753-78

BaumGR, Vail PR. 1988. Sequence stratigraphic concepts applied to Paleogene outcrops, Gulf and Atlantic basins. See Wilgus

et al 1988, pp. 309-27

BeaumontC. 1981. Foreland basins. Geophys.

J. R. Astron. Soc. 65:291-329

Bergman EA, Solomon SC. 1985. Earthquake

source mechanismsfrom body-waveforminversion and intraplate tectonics in the northern Indian Ocean. Phys. Earth Plant. Inter.

4:1-23

Berg OR, Woolverton DG, eds. 1985. Seismic

Stratigraphy H: An Integrated Approachto

HydrocarbonExploration. Am. Assoc. Petrol

Geol. Mem.39. 276 pp.

BlumMD.1993. Genesis and architecture of

incised valley fill sequences: a late Quaternary example from the Colorado River, Gulf

coastal plain of Texas. See Weimer& Posamentier 1993, pp. 259-84

Bosence DWJ, Pomar L, Waltham DA,

Lankester HG. 1994. Computer modeling

a Micocene carbonate platform, Mallorca,

Spain. Am.Assoc. Petrol. Geol. Bull. 78:24766

Boulton GS. 1990. Sedimentary and sea level

changesduring glacial cycles and their control on glacimarine facies architecture. In

Glacimarine Environments: Processes and

Sediments, ed. JA Dowdeswell,JD Scourse,

pp. 15-52. Geol. Soc. LondonSpec. Publ. 53.

423 pp.

BowringSA, Grotzinger JP. 1992. Implications

of newchronostratigraphyfor tectonic evolution of Wopmay

orogen, northwest Canadian

shield. Am. J. Sci. 292:1-20

BoydR, Suter J, PenlandS. 1989. Relation of

sequence stratigraphy to modernsedimentary

environments. Geology 17:926-29

Braun J, BeaumontC. 1989. A physical explanation of the relation betweenflank uplifts

and the breakupunconformityat rifted continental margins. Geology 17:760-64

Brink GJ, KeenanHG, BrownLF Jr. 1993. Deposition of fourth-order, post-rift sequences

and sequence sets, lower Cretaceous (lower

Valanginianto lower Aptian), PletmosBasin,

southern offshore, South Africa. See Weimer

&Posamentier 1993, pp. 393-410

BrownLF Jr, Fisher WL.1977. Seismic stratigraphic interpretation of depositional systems: examplesfrom the Brazilian rift and

pull-apart basins. See Payton1977, pp. 21348

Burton R, Kendall CGStC,Lerche I. 1987. Out

of our depth: on the impossibility of fathomingeustasy from the stratigraphic record.

Earth-Sci. Rev. 24:237-77

Cathles LM, Hallam A. 1991. Stress-induced

changes in plate density, Vail sequences,

epeirogeny, and short-lived global sea level

fluctuations. Tectonics 10:659-71

ChiocciFL. 1994. Veryhigh-resolution seismics

as a tool for sequence stratigraphy applied

to outcrop scale---examples from eastern

Tyrrhenian margin Holocene/Pleistocene deposits. Am.Assoc. Petrol. Geol. Bull. 78:37895

Christie-Blick N. 1990. Sequencestratigraphy

and sea-level changesin Cretaceous time. In

Cretaceous Resources, Events and Rhythms,

ed. RNGinsburg, B Beaudoin, pp. 1-21. Dordrecht: Kluwer, NATO

ASI Series C, 304.

352 pp.

Christie-Blick N. 1991. Onlap, offlap, and the

origin of unconformity-bounded

depositional

sequences. Mar. Geol. 97:35-56

Christie-Blick N, Biddle KT, eds. 1985. StrikeSlip Deformation,Basin Formation, and Sedimentation. Soc. Econ. Paleontol. Mineral.

Spec. Publ. No. 37. 386 pp.

Christie-Blick N, Driscoll, NW.1994. Relative

sea-level change and the origin of sequence

boundariesin tectonically active settings. Am.

Assoc. Petrol. Geol. Annu.Conv., Denver,Abstr. 121

Ctu’istie-Blick N, DysonIA, von der Borch CC.

1995. Sequencestratigraphy and the interpretation of NeoproterozoicEarth history. In

Terminal Proterozoic Stratigraphy and Earth

History, ed. AHKnoll, MRWalter. Precambrian Res. (Special issue). In press

Christie-Blick N, Grotzinger JP, yon der Botch

CC. 1988. Sequencestratigraphy in Proterozoic successions. Geology16:100-4

Christie-Blick N, Mountain GS, Miller KG.

1990. Seismic stratigraphic record of sealevel change. In Sea-Level Change,pp. 116140. Natl. Acad. Sci. Stud. Geophys.234pp.

CloetinghS. 1988.Intraplate stresses: a newelement in basin analysis. In NewPerspectives

in Basin Analysis (Pettijohn Volume),ed.

Kleinspehn, C Paola, pp. 205-23. NewYork:

�Annual Reviews

www.annualreviews.org/aronline

Annu. Rev. Earth. Planet. Sci. 1995.23:451-478. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.org

by Columbia University on 09/17/05. For personal use only.

474

CHRISTIE-BLICK & DRISCOLL

Springer-Verlag.

453pp.

bridgeUniv.Press. 274pp.

CloetinghS, McQueen

H, Lambeck

K. 1985. On Galloway

WE.1989.Geneticstratigraphic sea tectonic mechanism

for regionalsea-level

quencesin basinanalysisI: architectureand

variations,EarthPlanet.Sci. Lett. 75:157-66 genesis of flooding-surfacebounded

deposiCloetinghS, WonelR. 1985. Regionalstress

tional units. Am.Assoc.Petrol.Geol.Bull.

field of the IndianPlate. Geophys.

Res.Letts.

73:125-42

12:77-80

Garcfa-Mond6jarJ, Femfmdez-Mendiola

PA.

CrossTA,LessengerMA.1988.Seismicstratig1993. Sequencestratigraphy and systems

raphy.Annu.Rev.EarthPlanet.Sci. 16:319- tracts of a mixedcarbonateandsiliciclastic

54

platform-basinsetting: the albian of Lunada

DamG, SurlykF. 1992. Forcedregresssionsin

andSoba,northernSpain.Am.Assoc.Petrol.

a large wave-and storm-dominatedanoxic

Geol.Bull. 77:245-75

lake, Rhaetian-Sinemurian

KapStewartFor- GoetzeG, EvansB. 1979. Stress andtemperamation,F.ast Greenland.Geology20:749-52 ture in the bendinglithosphereas constrained

DemarestJMII, Kraft JC. 1987.Stratigraphic

by experimentalrock mechanics.Geophys.J.

recordof Quaternary

sea levels: implications R. Astron. Soc. 59:463-78

for moreancientstrata. In Sea-LevelFluctua- GreenleeSM,DevlinWJ, Miller KG,Mountain

tion andCoastalEvolution,ed. 13 Nummedal, GS,FlemingsPB. 1992. Integrated sequence

OHPilkey, JD Howard,pp. 223-39. Soc.

stratigraphy of Neogene

deposits, NewJerEcon.Paleontol.MineralSpec. PubLNo.41.

sey continentalshelf and slope: comparison

267pp.

with the Exxonmodel.Geol.Soc. Am.Bull.

Devlin WJ, Rudolph KW,ShawCA, Ehman

104:1403-1l

KD.1993.Theeffect of tectonicandeustatic Grotzinger JP, AdamsRD,McCormick

DS,Mycycles on accommodationand sequencerowP. 1989.Sequencestratigraphy,correlastratigraphic frameworkin the UpperCretions betweenWopmay

orogenand Kilohigok

taceous foreland basin of southwestern

basin, andfurther investigationsof the Bear

Wyoming.

See Posamentieret al 1993, pp.

Creek Group(GoulburnSupergroup),Dis501-20

trict of Mackenzie,

N.W.T.Geol.Surv. Can.

DottRHJr, ed. 1992.Eustasy:The Historical

Pap. 89-1C:107-19

Upsand Downsof a MajorGeologicalCon- Handford CR, Loucks RG, 1993. Carbonate

cept. Geol.Soc. Am.Mem.180. 111pp.

depositionalsequencesandsystemstracts-Driscoll NW.1992. Tectonicanddepositional

responsesof carbonateplatformsto relative

processesinferredfromstratal relationships. sea-level changes.SeeLoucks&Sarg 1993,

pp. 3-41

PhDdissertation. Columbia

Univ., NewYork.

464pp.

HaqBU.1,99I. Sequence

stratigraphy,sea-level

DriscollNW,HoggJR, Christie-BlickN, Karner change,andsignificancefor the deepsea. In

GD.1995.Extensionaltectonicsin the Jeanne Sedimentation,TectonicsandEustasy. Sead’ArcBasin:implicationsfor the timingof

Level Changesat Active Margins,ed. DIM

break-upbetweenGrandBanksand Iberia. In

Macdonald,

pp. 3-39. Int. Assoc.Sedimentol.

Opening

of the NorthAtlantic, ed, RAScrutSpec.Publ.12. 518pp.

ton. Geol.Soc. London

Spec.Publ.In press HaqBU,HardenbolJ, Vail PR. 1987.ChronolDdscollNW,KarnerGD.1994. Flexuraldeforogyof fluctuating

sea levelssincetheTriassic.

mationdue to Amazon

Fan loading: a feedScience235: 1156-67

backmechanism

affecting sedimentdelivery HaqBU,HardenbolJ, Yall PR. 1988. Mesozoic

to margins.Geology22:1015-18

and Cenozoicchronostratigraphyandcycles

EbdonCC, Fraser A J, Higgins AC,Mitchof sea-level change.SeeWilguset al 1988,

pp. 71-108

ener BC,Strank ARE.1990. The Dinantian

stratigraphy of the East Midlands:a seis- Helland-HansenW,KendallCGStC,Lerche I,

mostratigraphic

approach.J. Geol.Soc. Lon,

NakayamaK. 1988. A simulation of condon 147:519-36

tinental basin marginsedimentationin reEmbryAE1988. Triassic sea-level changes:

sponse to crustal movements,

eustatic sea

evidence from the CanadianArctic Arlevel change, and sediment accumulation

chipelago.SeeWilguset al 1988,pp. 249-59 rates. Math.Geol.20:777-802

EugsterHP,HardieLA.1975.Sedimentation

in Heller PL, AngevineCL, WinslowNS, Paola

an ancient playa-lakecomplex:the Wilkins C. 1988. Two-phase

stratigraphic modelof

Peak Member

of the GreenRiver Formation foreland-basinsequences.Geology16:501-4

of Wyoming.

Geol. Soc. Am.Bull 86:319-34 Heller PL, BowdlerSS, ChambersHP, Coogan

Flint SS, BryantID, eds. 1993.TheGeological JC, HagenES, et al. 1986.Timeof initial

Modellingof HydrocarbonReservoirs and

thrustingin the Sevierorogenicbelt, IdahoOutcropAnalogues.Int, Assoc. Sedimentol, Wyoming

and Utah. Geology14:388-91

Spec.Publ. 15. 269pp.

Hettinger PD, McCabe

PJ, ShanleyKW.1993.

FrakesLA,FrancisJE, SyktusJI. 1992.Climate Detailedfacies anatomy

of transgressiveand

Modesof the Phanerozoic.Cambridge:Cam- highstandsystemstracts fromthe UpperCre-

�Annual Reviews

www.annualreviews.org/aronline

Annu. Rev. Earth. Planet. Sci. 1995.23:451-478. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.org

by Columbia University on 09/17/05. For personal use only.

SEQUENCE STRATIGRAPHY

475

taceousof southernUtah,U.S.A.SeeWeimer Weimer&Posamentier1993, pp. 393-410

&Posamentier1993, pp. 43-70

KossJE, EthddgeFG, Schumm

SA. 1994. An

experimental

studyof the effectsof base-level

HolmesAE, Chdstie-Blick N. 1993. Origin

changeonfluvial, coastalplainandshelf sysof sedimentarycycles in mixedearbonatesiliciclastic systems: an examplefrom

tems.J. Sedimentol,Res. B64:90-98

the Canningbasin, WesternAustralia. See LambeckK. 1983. The role of compressive

forces in intracratonic basinformationand

Loucks&Sarg 1993, pp. 181-212

Jacquin T, Arnaud-VanneauA, AmandH,

mid,plate orogenics. Geophys.Res. Lett.

Ravenne

C, Vail PR.1991.Systemstracts and

10:845-48

depositionalsequences

in a carbonatesetting: LambeckK, McQueenHWS,Stephenson RA,

D. 1984. Thestate of stress within

a studyof continuousoutcropsfromplatform Denham

to basin at the scale of seismiclines. Mar

the Australian continent. Ann. Geophys.

Petrol Geol.8:122-39

2:723-41

JamesNP.1984. Shallowing-upward

sequences Lawrence

DT,DoyleM,AignerT. 1990.Stratiin carbonates. In Facies Models,ed. RG graphicsimulationof sedimentarybasins:

conceptsandcalibration, Am.Assoc,Petrol.

Walker,pp. 213-28.Toronto:Geosci.Can.

ReprintSer. 1. 317pp. 2nded.

Geol. Bull 74:273-95

JansaLF,Wade

JA. 1975.Geology

of the conti- LeckieDA,PosamentierHW,Lovell RWW,

eds.

nental marginoffNovaScotia andNewfound- 1991. NUNA

Conf. on High-ResolutionSeland. Geol.Surv.Can.Pap.74-30:51-105

quenceStratigraphy.Toronto:Geol.Assoc.

JerveyMT.1988.Quantitativegeologicalmod- Can.186 pp.

elingof siliciclastic rocksequences

andtheir LevyM,Chdstie-BlickN. 1991.Late Proteroseismicexpression.SeeWilguset a11988,pp.