Parker/Soanes/Roudavski, Transpositiones (2022), Volume 01, 183-236, DOI 10.14220/trns.2022.1.1.236

Dan Parker / Kylie Soanes / Stanislav Roudavski*

(University of Melbourne)

Interspecies Cultures and Future Design**

Abstract

This article introduces the notion of interspecies cultures and highlights its consequences

for the ethics and practice of design. This discussion is critical because anthropogenic

activities reduce the abundance, richness, and diversity of human and nonhuman cultures.

Design that aims to address these issues will depend on interspecies cultures that support

the flourishing of all organisms. Combining research in architecture and urban ecology, we

focus on the design of urban habitat-structures. Design of such structures presents practical, theoretical, and ethical challenges. In response, we seek to align design to advancing

knowledge of nonhuman cultures and more-than-human justice. We present interspecies

design as an approach that incorporates human and nonhuman cultural knowledge in the

management of future habitats. We ask: what is an ethically justifiable and practically

plausible theoretical framework for interspecies design? Our central hypothesis is that the

capabilities approach to justice can establish goals and evaluative practices for interspecies

design. To test this hypothesis, we refer to an ongoing research project that aims to help the

powerful owl (Ninox strenua) thrive in Australian cities. To establish possible goals for

future interspecies design, we discuss powerful-owl capabilities in past, present, and

possible future situations. We then consider the broader relevance of the capabilities

approach by examining human-owl cultures in other settings, globally. Our case-study

indicates that: 1) owl capabilities offer a useful baseline for future design; 2) cities diminish

many owl capabilities but present opportunities for new cultural expressions; and 3) more

ambitious design aspirations can support owl wellbeing in cities. The results demonstrate

* Dan Parker conducted the research, developed the argument for the manuscript, reviewed

literature, wrote the drafts, and produced visual materials. Kylie Soanes provided ecological

guidance and contributed to the development of the manuscript. Stanislav Roudavski conceived and developed the overarching ideas, directed the research, and contributed to all stages

of manuscript production. All authors contributed critically to the writing and revision of the

manuscript and gave the final approval for publication. The authors have no conflicts of

interest to declare.

** We respectfully acknowledge the Wurundjeri people who are the Traditional Custodians of the

Land on which this research took place. The project was supported by research funding from

the Australian Research Council Discovery Project DP170104010, Future Cities Grant (Melbourne Sustainable Society Institute), and William Stone Trust Fund (University of Melbourne). We thank Therésa Jones and Bronwyn Isaac for contributions to this research and

their feedback on the drafts of the article.

Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0

© 2022 V&R unipress | Brill Deutschland GmbH

�Parker/Soanes/Roudavski, Transpositiones (2022), Volume 01, 183-236, DOI 10.14220/trns.2022.1.1.236

184

Transpositiones 1, 1 (2022)

the capabilities approach can inform interspecies design processes, establish more equitable design goals, and set clearer criteria for success. These findings have important

implications for researchers and built-environment practitioners who share the goal of

supporting multispecies cohabitation in cities.

Keywords: Animal culture, capabilities approach, environmental ethics, interspecies design, multispecies justice, powerful owl

1.

Introduction

This article considers the notion of interspecies culture and highlights its consequences for the ethics and practice of design. These considerations are particularly important in the context of urban, landscape, and architectural design

but are also applicable to other activities that plan for and work to implement

better futures. To explore this topic, we investigate how design can respond to

advancing knowledge about nonhuman cultures and more-than-human justice.

This discussion is critical because anthropogenic activities reduce the abundance, richness, and diversity of all cultures, human and nonhuman.1 Unfortunately, design is responsible for much of this damage. Design that aims to

address these issues will depend on interspecies cultures that support the

flourishing of all organisms. As a starting point, we present an approach that

integrates cultural knowledge of multiple species. Combining research in architecture and urban ecology, we focus on urban habitat-structures.2 This work

addresses the urgent need to provide habitat that supports human and nonhuman cohabitation in cities.3 Design of such structures presents practical, theoretical, and ethical challenges. Engaging with these challenges, we ask: what is an

ethically justifiable and practically plausible theoretical framework for interspecies design? To address this question, we discuss conceptions of justice that

1 Thibaud Gruber et al., “Cultural Change in Animals: A Flexible Behavioural Adaptation to

Human Disturbance,” Palgrave Communications 5, no. 1 (2019): 1–9, https://doi.org/10/ggc

vtw.

2 See Stanislav Roudavski, “Multispecies Cohabitation and Future Design,” in Proceedings of

Design Research Society (DRS) 2020 International Conference: Synergy, ed. Stella Boess, Ming

Cheung, and Rebecca Cain (London: Design Research Society, 2020), 731–50, https://doi.org

/10/ghj48x.

3 Relevant fields include urban planning, urban design, landscape architecture, and architecture. See Kirsten M. Parris et al., “The Seven Lamps of Planning for Biodiversity in the City,”

Cities 83 (2018): 44–53, https://doi.org/10/gfsp47; Georgia E. Garrard et al., “Biodiversity

Sensitive Urban Design,” Conservation Letters 11, no. 2 (2018): e12411, https://doi.org/10/gf

sqmw; Margaret J. Grose, “Gaps and Futures in Working Between Ecology and Design for

Constructed Ecologies,” Landscape and Urban Planning 132 (2014): 69–78, https://doi.org/10/f

6qm7s; Alexander Felson, “The Role of Designers in Creating Wildlife Habitat in the Built

Environment,” in Designing Wildlife Habitats, ed. John Beardsley, vol. 34 (Washington: Harvard University Press, 2013), 223–24.

Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0

© 2022 V&R unipress | Brill Deutschland GmbH

�Parker/Soanes/Roudavski, Transpositiones (2022), Volume 01, 183-236, DOI 10.14220/trns.2022.1.1.236

Parker / Soanes / Roudavski, Interspecies Cultures and Future Design

185

include human and nonhuman beings. We hypothesize that the capabilities

approach can establish goals and evaluative practices for interspecies design. To

test this hypothesis, we refer to an ongoing research project that aims to help the

powerful owl (Ninox strenua) thrive in Australian cities. Using this project as

a characteristic example, we discuss past, present, and future communities of

humans and owls, highlighting the impact on the wellbeing of individuals and

ecosystems. Our analysis contributes to scholarship by reconsidering conservation in response to interspecies knowledge and testing ideas of justice in

application to design.

1.1.

Interspecies Cultures

Discourse within environmental humanities provides relevant background to

our notion of interspecies cultures. This discourse interrogates relations that

involve all life on earth.4 The ‘multispecies turn’ – also known as the ‘nonhuman’,

‘animal’, or ‘more-than-human’ turn – challenges ontological distinctions between nature and culture, human and nonhuman, and subject and object.5

Discourses of new materialism, posthumanism, actor-network theory, and

feminism also discuss the abandonment of such dualisms.6 Significantly, these

studies move away from human exceptionalism, recognising the interdependencies and entanglements of human and nonhuman entities. Multispecies studies aspire towards more diverse, rich, and autonomous ways of living

4 Deborah Bird Rose et al., “Thinking Through the Environment, Unsettling the Humanities,”

Environmental Humanities 1, no. 1 (2012): 1–5, https://doi.org/10/gg3q6p.

5 Piers Locke, “Multispecies Ethnography,” in The International Encyclopedia of Anthropology,

ed. Hilary Callan (Oxford: Wiley, 2018), 1–3, https://doi.org/10/ghcxtg. This turn engages

philosophy, anthropology, geography, art, cultural studies, literary studies, and history, among

others. Thom Van Dooren, Eben Kirksey, and Ursula Münster, “Multispecies Studies: Cultivating Arts of Attentiveness,” Environmental Humanities 8, no. 1 (2016): 1–23, https://doi.org

/10/gfsjh4. These fields also include design, planning, and sustainability, Donna Houston et al.,

“Make Kin, Not Cities! Multispecies Entanglements and ‘Becoming-World’ in Planning

Theory,” Planning Theory 17, no. 2 (2018): 190–212, https://doi.org/10/gdkqp6; Christoph

Rupprecht et al., “Multispecies Sustainability,” Global Sustainability 3 (2020): e34, https://doi.or

g/10/gjsbsb.

6 Donna Haraway, “A Cyborg Manifesto: Science, Technology, and Socialist-Feminism in the

Late Twentieth Century,” in Simians, Cyborgs and Women: The Reinvention of Nature (New

York: Routledge, 1991), 149–81; Diana Coole et al., New Materialisms: Ontology, Agency, and

Politics (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010); Rosi Braidotti, Posthuman Knowledge

(Medford: Polity, 2019); Bruno Latour, Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to ActorNetwork-Theory (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007).

Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0

© 2022 V&R unipress | Brill Deutschland GmbH

�Parker/Soanes/Roudavski, Transpositiones (2022), Volume 01, 183-236, DOI 10.14220/trns.2022.1.1.236

186

Transpositiones 1, 1 (2022)

together.7 In keeping with this objective, we aim to understand the interests and

experiences of others, recognising nonhuman knowledge, consciousness, intelligence, creativity, emotions, personality, intentions, and desires.8 Such understandings are useful to conceptualise human responsibilities towards other

beings of all kingdoms. Extending this discourse, we begin by outlining the need

for human cultures that support the flourishing of other taxa. Following, we

introduce how cultures emerge in nonhuman animals and outline the potential

to cultivate interspecies cultures.

1.1.1. Human Cultures

Without innovative modifications of prevalent human practices, the unfolding

environmental crisis is likely to grow catastrophically, provoking unstoppable

climate change, global-scale ecosystem collapse, and the destruction of human

and nonhuman lives.9 Even where species still survive, their ecological interactions may be effectively extinct.10 The loss of interaction with other lifeforms

and associated decline of human ecological knowledge, or the ‘extinction of

experience’, will make the reversal of these trends increasingly difficult.11 Resulting ‘shifting baselines’ for conservation can occur as the perceived condition

of ecosystems changes over time due to the loss of knowledge about past conditions.12 Consequent injustices arise through human-induced homogenisation

of species, languages, and cultural habits.13 Biodiversity, endangered species, and

extinction are cultural narratives that frame human perceptions of, and en7 Rosemary-Claire Collard, Jessica Dempsey, and Juanita Sundberg, “A Manifesto for Abundant Futures,” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 105, no. 2 (2015): 322–30,

https://doi.org/10/gftcks.

8 Danielle Celermajer et al., “Multispecies Justice: Theories, Challenges, and a Research Agenda

for Environmental Politics,” Environmental Politics 30, no. 1–2 (2020), 119–140, https://doi.o

rg/10/ghd4fd.

9 Valérie P. Masson-Delmotte et al., Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel

on Climate Change (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021).

10 Alfonso Valiente-Banuet et al., “Beyond Species Loss: The Extinction of Ecological Interactions in a Changing World,” Functional Ecology 29, no. 3 (2015): 299–307, https://doi.org

/10/f658d7.

11 Masashi Soga and Kevin J. Gaston, “Extinction of Experience: The Loss of Human–Nature

Interactions,” Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 14, no. 2 (March 2016): 94–101,

https://doi.org/10/f8jd9x.

12 S. K. Papworth et al., “Evidence for Shifting Baseline Syndrome in Conservation,” Conservation Letters 2, no. 2 (2009): 93–100, https://doi.org/10/dp2dcb.

13 Ricardo Rozzi, “Biocultural Ethics: From Biocultural Homogenization Toward Biocultural

Conservation,” in Linking Ecology and Ethics for a Changing World: Values, Philosophy, and

Action, ed. Ricardo Rozzi et al., Ecology and Ethics (Dordrecht: Springer, 2013), 9–32,

https://doi.org/10/dz2d.

Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0

© 2022 V&R unipress | Brill Deutschland GmbH

�Parker/Soanes/Roudavski, Transpositiones (2022), Volume 01, 183-236, DOI 10.14220/trns.2022.1.1.236

Parker / Soanes / Roudavski, Interspecies Cultures and Future Design

187

gagement with, nonhumans.14 Human worldviews, stories, media, scientific

studies, livelihoods, norms, and institutions reflect and influence relations

among plants, humans, and other animals.15 Recent scholarship calls for conservation practices to account for human-cultural differences, engage with local

communities, and incorporate social narratives on multispecies histories, locality, and Indigenous forms of knowledge.16 These cultural aspects have important implications for species conservation and human-wildlife conflict.17

1.1.2. Nonhuman Cultures

Culture is not unique to humans and research on nonhuman cultures is expanding in several fields. Recent reviews of biological literature demonstrate that

many nonhuman animals have culture.18 Acknowledgements that culture is not

unique to humans have also become more common in the humanities and social

sciences.19 Understood as the transmission of socially learned behaviours, cul-

14 Ursula K. Heise, Imagining Extinction: The Cultural Meanings of Endangered Species.

(Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016).

15 Brgit H. M. Elands et al., “Biocultural Diversity: A Novel Concept to Assess Human-Nature

Interrelations, Nature Conservation and Stewardship in Cities,” Urban Forestry & Urban

Greening, Urban green infrastructure – connecting people and nature for sustainable cities 40

(2019): 29–34, https://doi.org/10/gdb8p4.

16 Tanja M. Straka et al., “Conservation Leadership Must Account for Cultural Differences,”

Journal for Nature Conservation 43 (2018): 111–16, https://doi.org/10/gdvg9g; Lucy Taylor et

al., “Enablers and Challenges When Engaging Local Communities for Urban Biodiversity

Conservation in Australian Cities,” Sustainability Science (2021), https://doi.org/10/gmwp9h;

Alex Aisher and Vinita Damodaran, “Introduction: Human-Nature Interactions Through

a Multispecies Lens,” Conservation and Society 14, no. 4 (2016): 293–304, https://doi.org/10/gf

5j5h.

17 Carl D. Soulsbury and Piran. C. L. White, “Human-Wildlife Interactions in Urban Areas: A

Review of Conflicts, Benefits and Opportunities,” Wildlife Research 42, no. 7 (2016): 541–53,

https://doi.org/10/f 75rzg; Justin Schuetz and Alison Johnston, “Characterizing the Cultural

Niches of North American Birds,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 116, no. 22

(2019): 10868–73, https://doi.org/10/gf3x8n.

18 Philippa Brakes et al., “Animal Cultures Matter for Conservation,” Science 363, no. 6431

(2019): 1032–34, https://doi.org/10/ggcvtt; Andrew Whiten, “The Burgeoning Reach of Animal Culture,” Science 372, no. 6537 (2021): eabe6514, https://doi.org/10/gjndw3.

19 For examples in geography, sociology, and post-colonial studies, see: Timothy Hodgetts and

Jamie Lorimer, “Methodologies for Animals’ Geographies: Cultures, Communication and

Genomics,” Cultural Geographies 22, no. 2 (2015): 285–95, https://doi.org/10/f66r5n; Richie

Nimmo, “Animal Cultures, Subjectivity, and Knowledge: Symmetrical Reflections Beyond

the Great Divide,” Society & Animals 20, no. 2 (2012): 173–92, https://doi.org/10/f3znmv;

Lauren Corman, “He(a)Rd: Animal Cultures and Anti-Colonial Politics,” in Colonialism and

Animality: Anti-Colonial Perspectives in Critical Animal Studies, ed. Kelly Struthers Montford

and Chloë Taylor (Oxon: Routledge, 2020), 159–80.

Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0

© 2022 V&R unipress | Brill Deutschland GmbH

�Parker/Soanes/Roudavski, Transpositiones (2022), Volume 01, 183-236, DOI 10.14220/trns.2022.1.1.236

188

Transpositiones 1, 1 (2022)

ture is important for wellbeing and survival.20 Cultures influence migration

patterns, communication, food selection, foraging strategies, breeding-site

choices, courtship and mating, play, habitat use, and risk avoidance.21 Examples

of cultural expressions include place-specific dialects of genetically identical

birds, socially learned songs of whales, and regional use of tools by chimpanzees.22 Anthropogenic activities can alter or destroy such cultures. For instance,

extensive land clearing in Australia led to endangered honeyeaters losing their

songs and even adopting the songs of other birds, thereby making the males less

attractive to females.23 Novel conservation responses attempt to restore lost

cultures, for example through the use of drones to teach ibis cranes their forgotten migratory flightpaths.24 A significant challenge is to preserve existing

relationships while also imagining and permitting new cultures that involve

human and nonhuman cohabitants.

1.1.3. Development of Shared Cultures

We see this situation as an opportunity to cultivate interspecies cultures which

curate non-anthropocentric interactions and foster beneficial relationships between humans and nonhumans. This is possible because both human and

nonhuman animals continually reconstruct their cultures. Cultures develop

across generations, emerging as beliefs, knowledge, skills, traditions, or practices.25 Behavioural plasticity and innovation allow animals to adjust their behaviour to suit local conditions, such as those found in cities. As an example

where humans taught birds novel foraging techniques demonstrates, such cul-

20 Philippa Brakes et al., “A Deepening Understanding of Animal Culture Suggests Lessons for

Conservation,” Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 288, no. 1949 (2021):

20202718, https://doi.org/10/gjr2tm; Philippa Brakes, “Sociality and Wild Animal Welfare:

Future Directions,” Frontiers in Veterinary Science 6 (2019), https://doi.org/10/ggtk6b.

21 Whiten, “The Burgeoning Reach of Animal Culture.”

22 Lucy M. Aplin, “Culture and Cultural Evolution in Birds: A Review of the Evidence,” Animal

Behaviour, no. 47 (2019): 179–87, https://doi.org/10/gfsp4p; Hal Whitehead and Luke Rendell,

The Cultural Lives of Whales and Dolphins (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014); Carl

Safina, Becoming Wild: How Animals Learn to Be Animals (London: Oneworld Publications,

2020).

23 Ross Crates et al., “Loss of Vocal Culture and Fitness Costs in a Critically Endangered

Songbird,” Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 288, no. 1947 (2021):

20210225, https://doi.org/10/gjg86g.

24 Christian Sperger, Armin Heller, and Bernhard Voelkl, “Flight Strategies of Migrating

Northern Bald Ibises – Analysis of GPS Data During Human-Led Migration Flights,” AGIT –

Journal für Angewandte Geoinformatik, no. 3 (2017): 62–72, https://doi.org/10/gmwt82.

25 Alex Mesoudi, “Cultural Evolution: A Review of Theory, Findings and Controversies,” Evolutionary Biology 43, no. 4 (2016): 481–97, https://doi.org/10/gfsp3b.

Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0

© 2022 V&R unipress | Brill Deutschland GmbH

�Parker/Soanes/Roudavski, Transpositiones (2022), Volume 01, 183-236, DOI 10.14220/trns.2022.1.1.236

Parker / Soanes / Roudavski, Interspecies Cultures and Future Design

189

tures are influenceable and can spread rapidly throughout populations.26 The

ability to acquire new cultures presents opportunities, but also carries risks. On

one hand, cultural adaptation can help animals to adjust their behaviours in

response to changing environments.27 On the other, cultures can prevent the

spread of adaptive behaviours or lead to detrimental consequences.28 Individuals

can copy behaviours that result in harmful cultures.29 Further, there may be a risk

that humans continue to dominate the development of new cultures. In constructing their own niches, humans profoundly alter habitats and therefore

cultures, behaviours, populations, wellbeing, and even evolution of species.30

Highly human-altered ecosystems can intensify evolutionary traps, where population declines occur because animals make maladaptive selections of habitats,

mates, food, or other resources.31 Human social patterns and culturally informed

activities alter evolution in urban environments and require design strategies

that can facilitate adaptations to urban habitats instead of attempts to restore

historic conditions.32

1.2.

Interspecies Design

1.2.1. Nonhuman Knowledge

We argue that designers ought to develop intentional engagements with interspecies cultures.33 Design, as a process that shapes futures and impinges on

existing ecosystems, will play an important role in imagining new shared cultures. Interspecies design provides an opportunity for this endeavour. Understood as an approach to the management of future habitats, interspecies design

26 Lucy M. Aplin et al., “Experimentally Induced Innovations Lead to Persistent Culture via

Conformity in Wild Birds,” Nature 518, no. 7540 (2015): 538–41, https://doi.org/10/f3pfvt.

27 Brakes et al., “A Deepening Understanding of Animal Culture Suggests Lessons for Conservation.”

28 Richard O. Prum, The Evolution of Beauty: How Darwin’s Forgotten Theory of Mate Choice

Shapes the Animal World – and Us (New York: Doubleday, 2017).

29 Aplin, “Culture and Cultural Evolution in Birds.”

30 Marina Alberti et al., “The Complexity of Urban Eco-Evolutionary Dynamics,” BioScience 70,

no. 9 (2020): 772–93, https://doi.org/10/ghfn3f.

31 Bruce A. Robertson, Jennifer S. Rehage, and Andrew Sih, “Ecological Novelty and the

Emergence of Evolutionary Traps,” Trends in Ecology & Evolution 28, no. 9 (2013): 552–60,

https://doi.org/10/f5b6g7.

32 Simone Des Roches et al., “Socio-Eco-Evolutionary Dynamics in Cities,” Evolutionary Applications 14, no. 1 (2021): 248–67, https://doi.org/10/ghs8tw; L. Ruth Rivkin et al., “A

Roadmap for Urban Evolutionary Ecology,” Evolutionary Applications 12, no. 3 (2019): 384–

98, https://doi.org/10/ggbt5j.

33 Roudavski, “Multispecies Cohabitation and Future Design.”

Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0

© 2022 V&R unipress | Brill Deutschland GmbH

�Parker/Soanes/Roudavski, Transpositiones (2022), Volume 01, 183-236, DOI 10.14220/trns.2022.1.1.236

190

Transpositiones 1, 1 (2022)

entails a process of deliberate designing for and with more than one species.34

Potential applications of interspecies design range from small objects, products,

or graphic visualisations to urban landscapes, systems, or fictional worlds. Our

own research focuses on physical structures that support human and nonhuman

cohabitation. Examples include small-scale habitat-structures for bees, buildingscale attachments for mosses, tree-scale interventions for vertebrates, and

landscape-scale schemes for parklands and ecological infrastructure.35 These

projects move away from the prevailing approaches of design for nonhumans

which remain anthropocentric and seek to satisfy human criteria for success.36

For instance, contemporary design projects create pavilions that exploit animals

for artistic labour and structures that position animals as livestock for human

consumption.37 Yet non-anthropocentric forms of design are on the rise.38 Some

of these approaches seek to involve nonhumans in design processes without

exploitation or forced adjustment to human lifestyles.39

Going further, designers can grant nonhumans goal-setting and decisionmaking powers, and therefore abilities to influence the outcomes of design

processes.40 Nonhumans possess knowledge and perspectives that could offer

valuable contributions to the design of future environments. Many nonhumans

alter their environments through interspecies interactions and cultural ex-

34 Stanislav Roudavski, “Interspecies Design,” in Cambridge Companion to Literature and the

Anthropocene, ed. John Parham (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021), 147–62.

35 Roudavski, “Multispecies Cohabitation and Future Design.”

36 Stanislav Roudavski, “Notes on More-than-Human Architecture,” in Undesign: Critical

Practices at the Intersection of Art and Design, ed. Gretchen Coombs, Andrew McNamara,

and Gavin Sade (Abingdon: Routledge, 2018), 24–37, https://doi.org/10/czr8.

37 Jennifer R. Wolch and Marcus Owens, “Animals in Contemporary Architecture and Design,”

Humanimalia 8, no. 2 (2017): 1–26.

38 Carl DiSalvo and Jonathan Lukens, “Nonanthropocentrism and the Nonhuman in Design:

Possibilities for Designing New Forms of Engagement with and through Technology,” in

From Social Butterfly to Engaged Citizen: Urban Informatics, Social Media, Ubiquitous

Computing, and Mobile Technology to Support Citizen Engagement, ed. Marcus Foth (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2011), 421–35.

39 Monika Rosińska and Agata Szydłowska, “Zoepolis: Non-Anthropocentric Design as an

Experiment in Multi-Species Care,” in Who Cares? Proceedings of the 8th Biannual Nordic

Design Research Society, ed. Tuuli Mattelmäki et al. (Nordes 2019, Espoo: Aalto University

School of Arts, Design and Architecture, 2019), 1–7; Laura Forlano, “Posthumanism and

Design,” She Ji: The Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation 3, no. 1 (2017): 16–29,

https://doi.org/10/gfpf8d; Michelle Westerlaken and Stefano Gualeni, “Becoming with: Towards the Inclusion of Animals as Participants in Design Processes,” in Proceedings of the

Third International Conference on Animal-Computer Interaction (Milton Keynes: Association for Computing Machinery, 2016), 1–10, https://doi.org/10/f94dsg.

40 Emı̄lija Veselova and а İdil Gaziulusoy, “Implications of the Bioinclusive Ethic on Collaborative and Participatory Design,” The Design Journal 22, no. sup1 (2019): 1571–86,

https://doi.org/10/f9p9.

Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0

© 2022 V&R unipress | Brill Deutschland GmbH

�Parker/Soanes/Roudavski, Transpositiones (2022), Volume 01, 183-236, DOI 10.14220/trns.2022.1.1.236

Parker / Soanes / Roudavski, Interspecies Cultures and Future Design

191

pressions, such as nest building or ecological engineering of dams.41 Even organisms that do not construct their own habitat structures have agency that

includes abilities to act, bring about change, and affect others.42 Attempting to

incorporate such knowledge presents significant opportunities for future interspecies design that benefits nonhumans.

1.2.2. Ethics and Design

Integrating nonhumans into design processes presents unresolved ethical challenges.43 Namely, existing design ethics concentrates on human interests.44 In

response, we consider ethical aspects of interspecies cultures and design. Any

design undertakings must make ethical judgements on aesthetics, values to

prioritise, and trade-offs to make.45 Therefore, designers ought to consider

possible consequences of their designs when they attempt to improve existing

situations.46 In the context of interspecies design, humans are in an exceedingly

powerful position. Research on cultural ecosystem-services remains largely anthropocentric but provides insights into potential challenges. It considers approaches to preservation of cultural values, incorporation of diverse worldviews

into decision-making, and integration of multiple disciplines into deliberation

processes.47 Responding to these challenges, we ask: what is an ethically justifiable and practically plausible theoretical framework for interspecies design? Our

central hypothesis is that theories of justice can provide useful frameworks for

designing future environments that support interspecies cultures. Although

justice is a disputed term that has many different interpretations, its more-than41 Alexis J. Breen, “Animal Culture Research Should Include Avian Nest Construction,” Biology

Letters 17, no. 7 (2021): 20210327, https://doi.org/10/gnmk; Gillian Barker and John OdlingSmee, “Integrating Ecology and Evolution: Niche Construction and Ecological Engineering,”

in Entangled Life: Organism and Environment in the Biological and Social Sciences, ed. Gillian

Barker, Eric Desjardins, and Trevor Pearce (Dordrecht: Springer, 2014), 187–211.

42 For a range of examples, see Tuomas Räsänen and Taina Syrjämaa, eds., Shared Lives of

Humans and Animals: Animal Agency in the Global North (London: Routledge, 2017).

43 Roudavski, “Multispecies Cohabitation and Future Design.”

44 Jeffrey K. H. Chan, “Design Ethics: Reflecting on the Ethical Dimensions of Technology,

Sustainability, and Responsibility in the Anthropocene,” Design Studies 54 (2018): 184–200,

https://doi.org/10/gczncm.

45 Maurice Lagueux, “Ethics versus Aesthetics in Architecture,” The Philosophical Forum 35,

no. 2 (2004): 117–33, https://doi.org/10/b9qncw.

46 Tony Fry, “The Voice of Sustainment: Design Ethics as Futuring,” Design Philosophy Papers 2,

no. 2 (2004): 145–56, https://doi.org/10/gfsqdh.

47 Rachelle K. Gould, Joshua W. Morse, and Alison B. Adams, “Cultural Ecosystem Services and

Decision-Making: How Researchers Describe the Applications of Their Work,” People and

Nature 1, no. 4 (2019): 457–75, https://doi.org/10/gk97c7; David Cabana et al., “Evaluating

and Communicating Cultural Ecosystem Services,” Ecosystem Services 42 (2020): 101085,

https://doi.org/10/ggmn85.

Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0

© 2022 V&R unipress | Brill Deutschland GmbH

�Parker/Soanes/Roudavski, Transpositiones (2022), Volume 01, 183-236, DOI 10.14220/trns.2022.1.1.236

192

Transpositiones 1, 1 (2022)

human conceptualizations offer insights into ways of balancing human, nonhuman animal, and even non-sentient interests.48 Notably, ‘multispecies’ and

‘interspecies’ justice seek to recognise experiences and interests of all living

beings and provide a pragmatic frame to consider related ethical issues.49 Similar

to multispecies approaches, interspecies justice emphasises the co-presence of

many forms of life but puts emphasis on their relationships.50 This focus allows us

to consider cultures in living forms, especially in animals.51

2.

Methods

2.1.

Capabilities as Design Criteria

We investigate ideas of justice for interspecies design through the notion of

capabilities. The capabilities approach to justice aims to ensure that living beings

have fulfilled lives. Its early interpretations supported evaluations of human

wellbeing beyond the narrow notion of economic welfare.52 Capabilities referred

to the opportunity for a human or a group of humans to achieve what they value.53

48 Colin Hickey and Ingrid Robeyns, “Planetary Justice: What Can We Learn from Ethics and

Political Philosophy?,” Earth System Governance, Exploring Planetary Justice 6 (2020):

100045, https://doi.org/10/gjphcb; Frank Biermann and Agni Kalfagianni, “Planetary Justice:

A Research Framework,” Earth System Governance 6 (2020): 100049, https://doi.org/10/gkm

3qx.

49 Danielle Celermajer et al., “Justice Through a Multispecies Lens,” Contemporary Political

Theory 19 (2020): 475–512, https://doi.org/10/ggvkrv; Celermajer et al., “Multispecies Justice.” Val Plumwood, Environmental Culture: The Ecological Crisis of Reason (London:

Routledge, 2002). For the discussion of similar issues without the use of the term ‘interspecies’, see Adrian C. Armstrong, Ethics and Justice for the Environment (Milton Park:

Routledge, 2013).

50 Klaus Bosselmann, “Ecological Justice and Law,” in Environmental Law for Sustainability:

A Reader, ed. Benjamin J. Richardson and Stepan Wood (Oxford: Hart, 2006), 129–63; Klaus

Bosselmann, The Principle of Sustainability: Transforming Law and Governance (Aldershot:

Ashgate, 2008).

51 We acknowledge that biocentric justice is but one of the aspects of ecocentrism, along with

such frameworks as geocentric ethics and astroethics. Bosselman understood interspecies

justice as a concern for the nonhuman world and defined ecological justice as consisting of

three elements: intragenerational justice, intergenerational justice, and interspecies justice.

We focus on interspecies justice for pragmatic reasons. This allows us to focus on the considerations of cultures that are more readily acceptable in living forms, especially in animals.

Broader discussions of universal considerability are important but remain outside of scope

for this article.

52 For further background, see Ingrid Robeyns, “Capability Approach,” in Handbook of Economics and Ethics, ed. Jan Peil and Irene van Staveren (Cheltenham: Elgar, 2009), 39–46.

53 Amartya Sen, “Development as Freedom,” in The Globalization and Development Reader:

Perspectives on Development and Global Change, ed. J. Timmons Roberts, Amy Bellone Hite,

and Nitsan Chorev, 2nd ed. (1999; repr., Sussex: Wiley Blackwell, 2015), 525–48.

Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0

© 2022 V&R unipress | Brill Deutschland GmbH

�Parker/Soanes/Roudavski, Transpositiones (2022), Volume 01, 183-236, DOI 10.14220/trns.2022.1.1.236

Parker / Soanes / Roudavski, Interspecies Cultures and Future Design

193

More recent literature extends the capabilities approach to sentient animals.54

Like humans, nonhuman animals can flourish and their lives can go well or

badly.55 When a nonhuman animal cannot exercise a capability, the quality of

their life diminishes.56 Extending beyond the utilitarians’ focus on sentient animals’ capacity to feel pleasure and pain, the capabilities approach seeks to account for cognitive and social lives of animals.57 Going beyond the contractarians’

focus on compassion and humanity, this conception of the capabilities approach

treats animals as subjects with agency.58 More inclusive understandings of the

capabilities approach account for cultural groups and systems such as rivers or

forests.59 These approaches argue that harm to sentient or non-sentient organisms may hinder their capabilities for flourishing.60 Case-studies on stormwater

systems and urban forests demonstrate the usefulness of the capabilities approach to integrate human and nonhuman stakeholders into design and decision-making.61

54 Martha C. Nussbaum, Frontiers of Justice: Disability, Nationality, Species Membership

(Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007); Gail Tulloch, “Animal Ethics: The Capabilities Approach,” Animal Welfare 20 (2011): 3–10.

55 Elizabeth Cripps, “Saving the Polar Bear, Saving the World: Can the Capabilities Approach Do

Justice to Humans, Animals and Ecosystems?,” Res Publica 16, no. 1 (2010): 1–22,

https://doi.org/10/frj2kb.

56 Katy Fulfer, “The Capabilities Approach to Justice and the Flourishing of Nonsentient Life,”

Ethics and the Environment 18, no. 1 (2013): 19–42, https://doi.org/10/gfsp32.

57 Martha Nussbaum, “The Capabilities Approach and Animal Entitlements,” in The Oxford

Handbook of Animal Ethics, ed. Tom L. Beauchamp and Raymond G. Frey (New York: Oxford

University Press, 2011), 228–54.

58 Anders Schinkel, “Martha Nussbaum on Animal Rights,” Ethics and the Environment 13,

no. 1 (2008): 41–69, https://doi.org/10/fwsp4c.

59 David Schlosberg, Defining Environmental Justice: Theories, Movements, and Nature (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007): 148.

60 We acknowledge the potential limitations and critiques of the capabilities approach, including its possible intersections with anthropomorphism, individualism, universalism, and

paternalism. However, the potential benefits to individual organisms and entire ecosystems

justify further exploration of the capabilities approach in application to design. For the

discussion of these issues, see Fulfer, “The Capabilities Approach to Justice and the Flourishing of Nonsentient Life”; Jeremy Bendik-Keymer, “The Politics of Wonder: The Capabilities Approach in the Context of Mass Extinction,” in The Cambridge Handbook of the

Capability Approach, ed. Enrica Chiappero Martinetti (Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press, 2020), 247–244; Constanze Binder, “Cultural Diversity and the Capability Approach,”

in Agency, Freedom and Choice, ed. Constanze Binder, Theory and Decision Library A:

Rational Choice in Practical Philosophy and Philosophy of Science (Dordrecht: Springer,

2019), 105–27; Ian Carter, “Is the Capability Approach Paternalist?,” Economics and Philosophy 30, no. 1 (2014): 75–98, https://doi.org/10/gw8x; Cripps, “Saving the Polar Bear, Saving

the World.”

61 Anna Heikkinen et al., “Urban Ecosystem Services and Stakeholders: Towards a Sustainable

Capability Approach,” in Strongly Sustainable Societies, ed. Karl Johan Bonnedahl and Pasi

Heikkurinen (London: Routledge, 2019), 116–33.

Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0

© 2022 V&R unipress | Brill Deutschland GmbH

�Parker/Soanes/Roudavski, Transpositiones (2022), Volume 01, 183-236, DOI 10.14220/trns.2022.1.1.236

194

2.2.

Transpositiones 1, 1 (2022)

The Powerful Owl as a Case-Study

We test the capabilities approach in the context of an ongoing project that aims

to help large owls thrive in or around cities. Our component of the project focuses

on the design of habitat-structures for the powerful owl (Ninox strenua),

a threatened species in south-eastern Australia.62 We conduct this project in the

context of a broad effort by multiple parties to enjoy, study, and support powerful

owls.63 This integration into an existing interspecies context makes the case study

relevant as an illustration of complex interactions. These interactions include

multiple bioregions, owl communities, and human groups including The Powerful Owl Project run by BirdLife Australia, biologists and ecologists specialising

in powerful owls, local amateur collectives, urban municipalities, and management organisations.

This choice is also relevant as an instance where novel cultural imagination

across species will be increasingly necessary. Design and management decisions

that include powerful owls are important in response to ongoing habitat loss and

degradation. This case-study is also useful because it highlights applications of

justice theories to interspecies design that will be relevant in many other situations of environmental degradation and novel ecologies. Australian urbanisation and habitat destruction are illustrative of the global trends. Here, 10% of

terrestrial mammals went extinct since the arrival of the Europeans and over 16%

of birds are listed as threatened.64 Some 30% of threatened Australian species live

in cities.65 The plight of owls who attempt to find ways to live alongside humans is

similar to the challenges faced by many other species.

To establish possible goals for future interspecies design, we evaluate capabilities in human-dominated areas noting how powerful owls behaved (species

62 For details of our earlier work on habitat-structures for powerful owls, see Stanislav Roudavski and Dan Parker, “Modelling Workflows for More-than-Human Design: Prosthetic

Habitats for the Powerful Owl (Ninox strenua),” in Impact – Design with All Senses: Proceedings of the Design Modelling Symposium, Berlin 2019, ed. Gengnagel, Christoph et al.

(Cham: Springer, 2020), 554–64, https://doi.org/10/dbkp.

63 Powerful owls are the largest of the Australian nocturnal birds. Endemic to eastern and southeastern Australia, the conservation status of powerful owls is ‘endangered’ in the state of

Victoria and ‘vulnerable’ in the states of New South Wales and Queensland. For more information on the powerful owl and the Powerful Owl Project, see BirdLife Australia, “Powerful Owl,” accessed December 3, 2021, https://www.birdlife.org.au/bird-profile/powerful-o

wl.

64 Michelle Ward et al., “A National-Scale Dataset for Threats Impacting Australia’s Imperilled

Flora and Fauna,” Ecology and Evolution (2021): 1–13, https://doi.org/10/gq37.

65 Christopher D. Ives et al., “Cities Are Hotspots for Threatened Species: The Importance of

Cities for Threatened Species,” Global Ecology and Biogeography 25, no. 1 (2016): 117–26,

https://doi.org/10/f 76nk2.

Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0

© 2022 V&R unipress | Brill Deutschland GmbH

�Parker/Soanes/Roudavski, Transpositiones (2022), Volume 01, 183-236, DOI 10.14220/trns.2022.1.1.236

Parker / Soanes / Roudavski, Interspecies Cultures and Future Design

195

norms) and fared (wellbeing) before colonisation and urbanisation.66 This helps

to provide benchmarks for possible restoration through design.67 We use this

approach because the restoration of capabilities may prevent future harm and

compensate for past injustices. In four steps, we consider the:

1. Powerful owls in the past: evolved capabilities of owls in pre-colonial Australian contexts (~300 years ago and earlier). We first outline the historical

context of human and owl cultures and explain the environments that owls

evolved to accept. We then use historical and scientific literature to list 12

capabilities of powerful owls. Instead of relying on predetermined sets, we

recognise that different purposes may require different lists of capabilities.68

We organise the list of powerful-owl capabilities into three categories: health,

autonomy, and affiliation.69 These categories are sufficiently broad to allow

comparisons with capabilities of other stakeholders, such as trees and possums, in future studies.

2. Powerful owls in the present: expression of capabilities by owls in Australian

cities. To understand how colonisation and urbanisation restricted or enabled

powerful-owl capabilities, we collect examples of owl behaviour from scientific literature, news articles, visual media, anecdotes, firsthand observations,

and grey literature. Cross-checking these observations against the list of 12

capabilities (step 1), we identify the extent to which cities restrict or enable owl

behaviours.

66 For background on this approach, see Nicolas Delon, “Animal Capabilities and Freedom in

the City,” Journal of Human Development and Capabilities 22, no. 1 (2021): 131–53,

https://doi.org/10/gmnmnb.

67 We consider this approach to be especially valuable in cities, where attempts to return the

environment to previous states are unfeasible due to the expanse of existing infrastructure,

extent of degradation, and possible lack of reference points for restoration. Further, aims to

restore pristine wilderness (free of human influence) are not necessarily possible or desirable,

especially where Indigenous communities held centuries-long land-management practices.

68 For background, Nussbuam’s theory of justice lists ten general capabilities that humans and

sentient animals should be entitled to up a minimum threshold: life; bodily health; bodily

integrity; senses, imagination and thought; emotion; practical reason; affiliation; other species; play; and control over one’s environment. See Nussbaum, Frontiers of Justice: Disability,

Nationality, Species Membership.

69 We acknowledge that this approach inevitably generalises and ask readers to treat the lists as

an illustration rather than an exhaustive list of all possible capabilities. We do not claim that

owls could utilize all capabilities or that owl wellbeing cannot improve beyond this state. Also

note that our analysis also relies on more recent literature about owl behaviour in areas with

less human disturbance because researchers only recently made the first assessments of the

distribution, abundance, and conservation status of powerful owls. See Department of Environment and Conservation, “Recovery Plan for the Large Forest Owls: Powerful Owl (Ninox

strenua), Sooty Owl (Tyto tenebricosa) and Masked Owl (Tyto novaehollandiae),” Approved

NSW Recovery Plan (Sydney: DEC, 2006).

Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0

© 2022 V&R unipress | Brill Deutschland GmbH

�Parker/Soanes/Roudavski, Transpositiones (2022), Volume 01, 183-236, DOI 10.14220/trns.2022.1.1.236

196

Transpositiones 1, 1 (2022)

3. Powerful owls in the future: effects of current and aspirational design and

management. To understand how interspecies design could impact the capabilities of powerful owls in cities, we extrapolate the trends established by

current design and management actions. We then draw from recent design

proposals to put forward possible interspecies approaches that could better

support the goal of restoring capabilities.

4. Implications beyond powerful owls. To consider potential applications beyond the case of the powerful owl, we consider capabilities of other owls in

other settings. We examine three categories of animals: captive, liminal, and

wild.70 Within these categories, we identify four representative human-owl

cultures based on a taxonomy of human-animal relations that distinguishes

between animals engaged in display and performance as well as meat, pets,

experimental subjects, workers, and symbols.71

We conclude with a discussion on the ethical challenges of designing for interspecies cultures and posit directions for further research based on this knowledge.

3.

Results

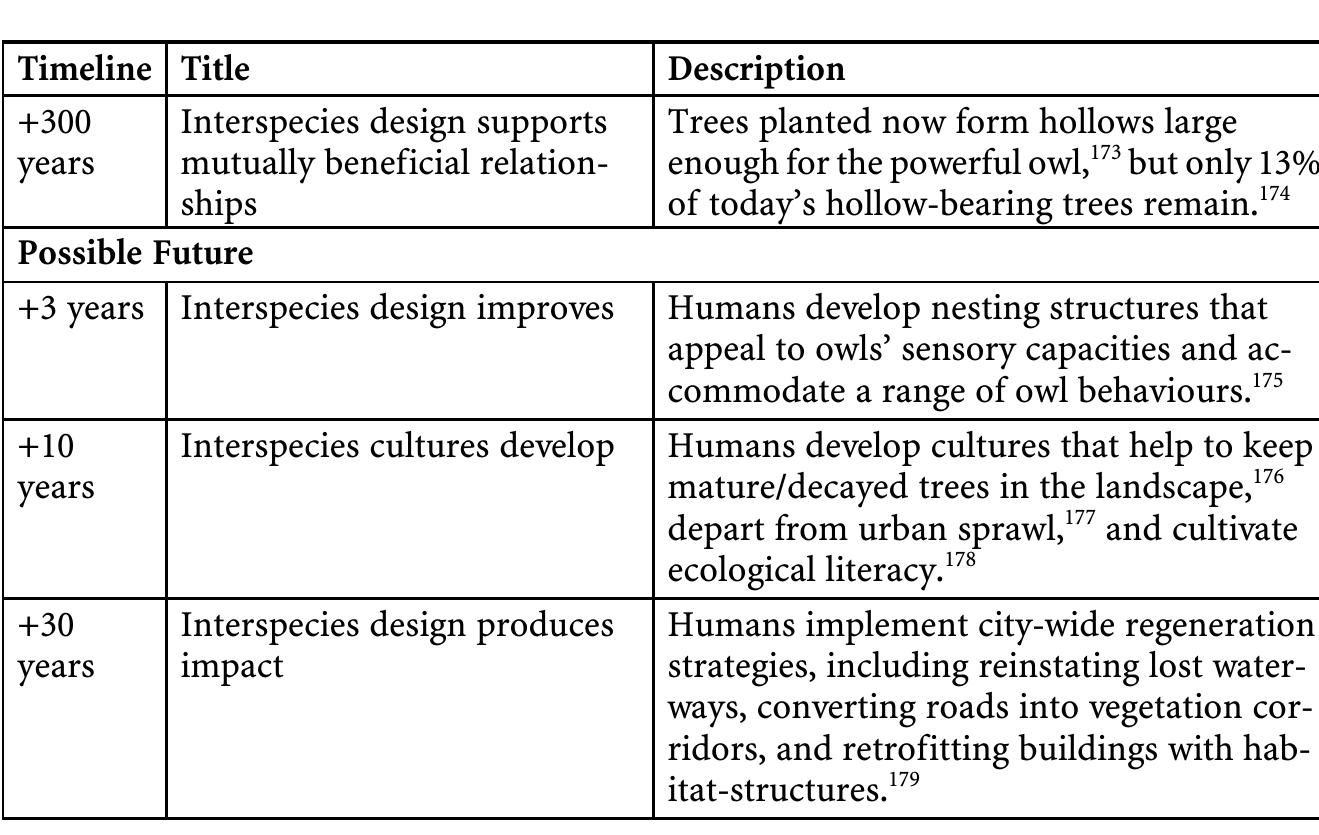

The Results section presents our findings in four parts using tables and diagrams:

1. Section 3.1. collects an array of powerful-owl capabilities, offering a baseline

for future design.

2. Section 3.2. finds that cities diminish many capabilities of powerful owls but

present opportunities for new cultural expressions, highlighting the need for

design to target multiple aspects of powerful-owl wellbeing.

3. Section 3.3. develops visual mapping which indicates the possibilities for

design to help restore powerful-owl capabilities in cities in a way that moves

beyond current design and management strategies.

4. Section 3.4. presents the reusability of our approach in other cases, ascertaining the opportunities for context-specific and place-based applications to

other taxa and human-owl cultures.

70 For background on these categories, refer to Section 3.4. and see Sue Donaldson and Will

Kymlicka, Zoopolis: A Political Theory of Animal Rights (New York: Oxford University Press,

2011).

71 Margo DeMello, Animals and Society: An Introduction to Human-Animal Studies, 2nd ed.

(2012; repr., New York City: Columbia University Press, 2021).

Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0

© 2022 V&R unipress | Brill Deutschland GmbH

�Parker/Soanes/Roudavski, Transpositiones (2022), Volume 01, 183-236, DOI 10.14220/trns.2022.1.1.236

Parker / Soanes / Roudavski, Interspecies Cultures and Future Design

3.1.

197

Powerful Owls in the Past: Cultural Interactions as a Baseline for Design

This section describes past lifestyles and capabilities of powerful owls as a

baseline for future design. Archaeological records confirm that human-owl

cultures are old. Owls played an important role in the construction of landscapes,

contributed to the senses of place and community, and even influenced the

making of humanity.72 During the Late Pleistocene, owls increasingly shaped the

material, cognitive, and social worlds of their human co-dwellers, prompting

owl-directed human behaviours such as visual culture. Ninox owls, including

powerful owls and the closely related Tasmanian spotted owl (Ninox novaeseelandiae), likely underwent an ancient radiation in Gondwanaland.73 Powerful

owls evolved to thrive in the old-growth forests and woodlands of south-eastern

Australia (Fig. 1).74 They coexisted with the Indigenous Australian communities

who thought that owls were important.75 Table 1 highlights how these conditions

provided habitat and resources which enabled owls’ capabilities. This offers

habitat designers a benchmark for design that attempts to support a broad array

of cultures and behaviours.76

3.2.

Powerful Owls in the Present: Design for Survival in Novel Ecologies

To identify opportunities for design, this section describes how powerful owls

changed their behaviours in cities. Since European colonisation, exploitative

land-management caused major ecosystem changes in south-eastern Australia.77

Land-clearing destroyed over 50% of forest and woodland in New South Wales

and 65% in Victoria.78 These changes restrict the lives of owls and lead to declines

72 Shumon Hussain, “The Hooting Past. Re-Evaluating the Role of Owls in Shaping HumanPlace Relations Throughout the Pleistocene,” Anthropozoologica 56, no. 3 (2021): 39–56,

https://doi.org/10/gkrfkt.

73 Department of Environment and Conservation, “Recovery Plan for the Large Forest Owls.”

74 Peter Jeffrey Higgins, Handbook of Australian, New Zealand & Antarctic Birds (Melbourne:

Oxford University Press, 1990).

75 Philip A. Clarke, “Birds as Totemic Beings and Creators in the Lower Murray, South Australia,” Journal of Ethnobiology 36, no. 2 (2016): 277–93, https://doi.org/10/gknqjp.

76 Refer to Supplementary Materials (A) for references and further details in support of Table 1.

77 Recent accounts have underestimated the magnitude of this ecological change, risking

‘shifting baselines’ for conserving owl habitat. See Rohan J. Bilney, “Poor Historical Data

Drive Conservation Complacency: The Case of Mammal Decline in South-Eastern Australian

Forests,” Austral Ecology 39, no. 8 (2014): 875–86, https://doi.org/10/f6qqnd.

78 Department of Sustainability and Environment, “Action Statement: Powerful Owl,” Flora and

Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 (East Melbourne: Department of Sustainability and Environment,

1999).

Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0

© 2022 V&R unipress | Brill Deutschland GmbH

�Parker/Soanes/Roudavski, Transpositiones (2022), Volume 01, 183-236, DOI 10.14220/trns.2022.1.1.236

198

Transpositiones 1, 1 (2022)

Fig. 1. Powerful-owl chicks in a hollow of a large-old tree. Photography: Nick Bradsworth

in owl populations.79 Present-day owl populations exist in dramatically modified

landscapes and are increasingly common in cities.80 Although researchers once

thought that powerful owls are habitat specialists restricted to old-growth forests,

powerful owls now inhabit Australia’s densest cities including Sydney and

Melbourne.81 This suggests that owls can adapt to, tolerate, or even benefit from

human-dominated landscapes (Fig. 2). However, cities present owls with several

challenges which threaten their wellbeing and prospects of long-term survival.82

Urbanisation reduces the availability of critical habitat-structures that owls depend on, such as tree cover, structurally complex vegetation, and access to wa-

79 Higgins, Handbook of Australian, New Zealand & Antarctic Birds.

80 Raylene Cooke et al., “Powerful Owls: Possum Assassins Move into Town,” in Urban Raptors:

Ecology and Conservation of Birds of Prey in Cities, ed. Clint W. Boal and Cheryl R. Dykstra

(Washington: Island Press, 2018), 152–165.

81 Ian McAllan and Dariel Larkins, “Historical Records of the Powerful Owl Ninox strenua in

Sydney and Comments on the Species’ Status,” Australian Field Ornithology 22, no. 1 (2016):

29–37; Raylene Cooke, Robert Wallis, and John White, “Use of Vegetative Structure by

Powerful Owls in Outer Urban Melbourne, Victoria, Australia-Implications for Management,” Journal of Raptor Research 36, no. 4 (2002): 294–99.

82 Refer to Supplementary Materials (B) for references and further details in support of Table 2.

Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0

© 2022 V&R unipress | Brill Deutschland GmbH

�Parker/Soanes/Roudavski, Transpositiones (2022), Volume 01, 183-236, DOI 10.14220/trns.2022.1.1.236

Parker / Soanes / Roudavski, Interspecies Cultures and Future Design

Capabilities

Health

Examples

Live a normal length life, in good health and free from bodily intrusion or violence, with

opportunities to develop a full range of senses.

Rest

Choose favourable roosting sites.

Access perches with good shelter;

Feed

Practice typical hunting and foraging

strategies and choose food.

Exhibit rare prey-holding behaviour

for food storage or territorial display;

maintain a mixed diet.

Access water to drink, clean self, or

regulate body temperature.

Bathe and drink in freshwater pools.

Access sources of pleasure, enjoy

recreational activities, or have adequate

sensory stimulation.

Ferry bark-strips, snatch at foliage,

swoop, hang upside-down on branches,

and chase animals.

Bathe

Play

199

Make own decisions and have freedom of movement.

Move

Fledge

Disperse

Defend

Perform movements that support prey

handling, foraging, and transit.

Access adequate structures to land

on when leaving nest and gain

independence.

Access complex vegetative structure to

Disperse into adequate territories and

establish own home-range.

Disperse into areas without clustering;

establish home-range in high-quality

habitat.

Defend territory from threats.

Protect territory from intruders, including

displays or swooping.

Form rewarding relationships with others and have choice of attachment to others.

Socialise

Learn

Develop and express the local dialect and

Develop local knowledge and expertise

others.

‘woo-hoo’ call.

Learn hunting strategies from parents

and siblings or the routines of prey.

Mate

Find potential mates, court, and mate.

Bleat, duet, preen, gift food, and copulate.

Nest

Access potential nesting sites to incubate

eggs and raise young.

Access large tree-hollows.

Table 1. Baseline capabilities of powerful owls. Colours distinguish different capabilities to assist

cross-referencing between tables and diagrams

Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0

© 2022 V&R unipress | Brill Deutschland GmbH

�Parker/Soanes/Roudavski, Transpositiones (2022), Volume 01, 183-236, DOI 10.14220/trns.2022.1.1.236

200

Transpositiones 1, 1 (2022)

terways.83 This reduces the opportunities for owls to bathe, fledge, disperse,

defend, socialise, learn, mate, and nest (Table 2). The restoration of these capabilities can serve as a target for design which moves beyond the usual goals of

supporting bare-minimum biological necessities and towards other factors that

are important for wellbeing and survival.

Fig. 2. Powerful owls expressing novel behaviours and inhabiting urban contexts. Top left: tearing

a cooler bag. Top right: hanging off shorts (Credit: Choosypix). Right middle: using a birdbath

(Credit: Andrew Gregory). Bottom left: nesting in an arboreal termite mound (Credit: Ofer Levy).

Bottom right: roosting in an inner-urban/introduced tree (Credit: Lian Hingee)

3.3.

Powerful Owls in the Future: Designing for Flourishing

This section considers whether current and possible future design and management strategies could meet the design targets established above. Most of the

current design for owls relates to nesting. Provision of nesting structures is

particularly important because the tree hollows suitable for nesting are rare and

declining in cities. In one Australian city where powerful owls are present, the

number of hollow-bearing trees in urban greenspace is likely to decline by 87%

83 Bronwyn Isaac et al., “Does Urbanization Have the Potential to Create an Ecological Trap for

Powerful Owls (Ninox strenua)?,” Biological Conservation 176 (2014): 1–11, https://doi.org

/10/f6c3zf.

Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0

© 2022 V&R unipress | Brill Deutschland GmbH

�Parker/Soanes/Roudavski, Transpositiones (2022), Volume 01, 183-236, DOI 10.14220/trns.2022.1.1.236

Parker / Soanes / Roudavski, Interspecies Cultures and Future Design

Capabilities

Health

Rest

Feed

Bathe

Play

201

Examples

Owls are subject to several health risks in cities including car strikes, electrocution,

attacks from introduced species, and secondary poisoning. Availability of healthcare in

veterinary clinics or sanctuaries does not substantially alter this overarching trend.

Limited sites for resting; possible

susceptibility to disturbance including,

noise, light, and infrastructure.

Use of sub-par roosts that do not allow

Less diversity but greater abundance of

prey including possums.

Smaller home-ranges; novel food such as

Less availability of riparian areas for

bathing.

Use of human-made bathing spots like

bird ponds.

Relatively unchanged opportunities

to play, for example by swinging on

branches.

Snatching of human-made objects of

stimulation, such as clothing, cooler bags,

and tea-towels.

roosting sites such as tennis-court fences,

powerlines, and cars.

Owls maintain autonomy in cities, but the destruction of habitats has reduced

to live good lives by undermining freedoms and restricting options.

Move

Fledge

Disperse

Continued freedom of movement but with

understory or tree-lopping practices.

adoption of orphan owls; human aid in

Less availability of suitable areas for

Young owls remain with their parents for

longer.

mortality, inbreeding and lower fecundity.

Defend

unsuitable habitat to connect to another

habitat patch.

Possibly more threats to defend territory

from.

Techniques to defend territories

from other owls and the mobbing of

introduced birds.

wellbeing. Some humans poach owls. Some urban owls habituate to human presence

and enter places near humans.

Socialise

Fewer opportunities to socialise with

populations.

Interaction with humans and possible

change in vocalizations between regions.

Learn

Greater need to adapt to cope with new

threats.

Development of personality traits that

help urban exploitation.

Mate

More human disturbance and fewer

Possible breeding failure and infanticide

due to human presence.

Nest

Less opportunity to reproduce because of

the shortage and decline of old hollowbearing trees.

Use of novel structures including

introduced trees, human-made hollows,

or arboreal termite nests.

Table 2. Present-day capabilities of powerful owls. Colours distinguish different capabilities to

assist cross-referencing between tables and diagrams

Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0

© 2022 V&R unipress | Brill Deutschland GmbH

�Parker/Soanes/Roudavski, Transpositiones (2022), Volume 01, 183-236, DOI 10.14220/trns.2022.1.1.236

202

Transpositiones 1, 1 (2022)

over 300 years under existing management practices.84 Tree-planting alone is

inadequate because it can take several hundred years until tree hollows become

large enough for powerful owls.85 In response, most of the current designs for

powerful owls propose human-made tree hollows such as nest boxes or similar

structures (Fig. 3). While the human-cultural interest in supporting owls is encouraging, there is only one recorded occasion of a powerful owl using a humanmade hollow, and even then, only one chick survived.86 Unsurprisingly, most

advice for the management of future environments for owls urges managers not

to rely solely on nest boxes. Instead, existing guidelines for planners, architects,

and landscape architects focus on regeneration of vegetation, preservation of

existing vegetation, and reduction of human impact on owls.87 These mitigation

efforts, combined with improvements to human-made hollows, may help to

maintain powerful owl populations in the short term while revegetated environments mature. Still, the goal of reconfiguring cities in a way that allows owls to

utilise their range of capabilities may necessitate cultural changes that depart

from the status quo of urban management (Fig. 4). This diagram shows how

design goals could help to support expressions of powerful owl capabilities

documented in Tables 1 and 2. The irregular edges of the lines indicate the

approximate nature of such predictions. This visual mapping clearly indicates

the need and possibility for more ambitious design to support powerful-owl

flourishing in response to the destructive human-activities in recent pasts and

projected futures of cities.88

84 Under a worst-case scenario, human activities such as clearing land for stock grazing and

urban development may completely remove hollow-bearing trees from the urban landscape

within 115 years. Even under a best-case scenario, the number of hollow-bearing trees will

likely decline. See Darren S. Le Roux et al., “The Future of Large Old Trees in Urban

Landscapes,” PLOS ONE 9, no. 6 (2014): e99403, https://doi.org/10/f6dg7p.

85 Philip Gibbons and David B. Lindenmayer, Tree Hollows and Wildlife Conservation in Australia (Collingwood: CSIRO, 2002).

86 Ed McNabb and Jim Greenwood, “A Powerful Owl Disperses into Town and Uses an Artificial

Nest-Box,” Australian Field Ornithology 28, no. 2 (2011): 65–75.

87 For example, advice developed by owl-protection groups encourages (1) regeneration of

habitat by introducing indigenous trees that will eventually bear hollows along waterways and

streets, providing pathways across roads using cables/poles, and planting complex vegetation

on both public and private property, (2) preservation of habitat by protecting riparian areas,

vegetation patches, and tree corridors, as well as retaining and pruning trees instead of

removing, and (3) reduction of vegetation removal or direct harm to owls when constructing

buildings (e. g., installing bird-sensitive windows that reduce collisions with glass), constructing tracks and paths, and introducing lighting near core habitat areas. See Robin

Buchanan, Helen Wortham, and Powerful Owl Coalition, Protecting Powerful Owls in Urban

Areas: Powerful Owls Benefit People (Turramurra: STEP, 2018).

88 Refer to Supplementary Materials (C) for references in support of Figure 4.

Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0

© 2022 V&R unipress | Brill Deutschland GmbH

�Parker/Soanes/Roudavski, Transpositiones (2022), Volume 01, 183-236, DOI 10.14220/trns.2022.1.1.236

Parker / Soanes / Roudavski, Interspecies Cultures and Future Design

203

Fig. 3. Human-made hollows for powerful owls. Top left: carved hollow. Top right: carved log.

Middle left: nest box. Middle right: repurposed wheelie-bin (Credit: Gio Fitzpatrick). Bottom left:

hempcrete hollow. Bottom right: 3D printed wood hollow. Photography by the authors unless

stated otherwise

3.4.

Beyond Powerful Owls: Capabilities in Other Taxa

While our case-study focuses on urban-dwelling powerful owls in south-eastern

Australia, the capabilities approach has broad relevance to other situations. Table

3 presents these implications with examples of human-owl cultures at different

sites and outlines the possible impacts on owl capabilities. Fig. 5 takes the scenarios from Table 3 and illustrates how these human attitudes can affect the

likelihood of owls utilising their capabilities. The irregular edges of the circles

indicate the approximate nature of such predictions. Awareness of these interspecies relationships can inform the composition of design teams and help to

establish more equitable objectives. The form of interspecies design will vary

depending on whether the species are captive, liminal, or wild. For instance, owls

raised in captivity will have more tolerance towards humans in comparison to

those captured in the wild.89 In the case of powerful owls, captive birds may live

89 Aurora Potts, “Captive Enrichment for Owls (Strigiformes),” Journal of Wildlife Rehabilitation

36, no. 2 (2016): 11–29.

Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0

© 2022 V&R unipress | Brill Deutschland GmbH

�Parker/Soanes/Roudavski, Transpositiones (2022), Volume 01, 183-236, DOI 10.14220/trns.2022.1.1.236

204

Transpositiones 1, 1 (2022)

Fig. 4. Design goals for capabilities. Right half: the impact of past events on powerful-owl capabilities (multi-coloured). Left half: projected situations under current design and management

(grey text) and possible impact of design on powerful-owl capabilities in the future (blue).

Colours distinguish different capabilities to assist cross-referencing between tables and diagrams. Line thicknesses indicate the likelihood of powerful owls expressing their capabilities,

where thick = likely, medium = possible, thin = unlikely

Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0

© 2022 V&R unipress | Brill Deutschland GmbH

�Parker/Soanes/Roudavski, Transpositiones (2022), Volume 01, 183-236, DOI 10.14220/trns.2022.1.1.236

Parker / Soanes / Roudavski, Interspecies Cultures and Future Design

Relationship

Examples

Possible Impact on Capabilities

Captive

Entertainment

Companion

attachment to others and freedom of

Patient

Liminal

Wild

Table 3. Human-owl cultures globally and their potential impact on owl capabilities

Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0

© 2022 V&R unipress | Brill Deutschland GmbH

205

�Parker/Soanes/Roudavski, Transpositiones (2022), Volume 01, 183-236, DOI 10.14220/trns.2022.1.1.236

206

Transpositiones 1, 1 (2022)

Rest

Feed

Bathe

Play

Move

Fledge

Disperse

Defend

Socialise

Learn

Mate

Nest

Experiment

Entertainer

Companion

Human-Owl Relationships

Patient

Labour

Urban Visitor

Synanthrope

Mutualist

Omen

Resource

Recluse

Human Thought

Capabilities

Fig. 5. Illustration of the potential impacts of human-owl cultures on owl capabilities based on

the examples in Table 3. Colours distinguish different capabilities to assist cross-referencing

between tables and diagrams. Circle sizes indicate the likelihood of owls expressing their capabilities, where large = likely, medium = possible, small = unlikely. Rows: representative humanowl relationships. Columns: capabilities of owls

severely restricted lives and develop behaviours that are radically different to

those typical in the wild. Wild powerful owls, when hospitalised or in aviaries, are

often unsettled, stressed, aggressive towards handlers, and difficult to keep.90

Wild or liminal powerful owls also exhibit considerable behavioural differences

in different regions.91 This behavioural plasticity highlights the need for interspecies design that is context-specific and place-based.

90 Fiona Park, “Behavior and Behavioral Problems of Australian Raptors in Captivity,” Seminars

in Avian and Exotic Pet Medicine 12, no. 4 (2003): 232–41, https://doi.org/10/bjjhsc.

91 For example, urban owls demonstrate more tolerance of humans than rural conspecifics

(refer to Table 2). For evidence of different behaviours across regions of Australia, see

Higgins, Handbook of Australian, New Zealand & Antarctic Birds.

Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0

© 2022 V&R unipress | Brill Deutschland GmbH

�Parker/Soanes/Roudavski, Transpositiones (2022), Volume 01, 183-236, DOI 10.14220/trns.2022.1.1.236

Parker / Soanes / Roudavski, Interspecies Cultures and Future Design

4.

Discussion

4.1.

Case-Study Findings and Limitations: Extending the Capabilities

Approach

207

The objective of this article is to establish goals and evaluative practices for

interspecies design. Our results demonstrate that the capabilities approach can

support this objective by proposing and testing future-oriented design possibilities with respect to interspecies cultures. Our case-study focused on owls and

points to the need for alternative design approaches that imagine what future

interspecies design and culture can entail. These approaches should aim to incorporate more-than-human cultural interactions into design thinking (Section

3.1.), provide targets for design that recognise rich and diverse lives of nonhuman

species (Section 3.2.), and encourage more ambitious design aspirations beyond

business-as-usual (Section 3.3.).

As an initial step towards developing an ethically justifiable and practically

plausible theoretical framework for interspecies design, our examples exclude

significant aspects that will require further research. In this paragraph, we list

some of the limitations of the work presented here and the planned further

research.

1. This article generalises capabilities for all powerful owls without detailed

considerations of their local cultures or individualities. Future research ought

to map and compare the capabilities and interactions of owls within interspecies communities across distinct bioregions and novel ecologies.

2. We focus on the interactions of powerful owls and humans, largely excluding

other stakeholders. Future work should include relations with different

human groups, from enthusiasts to scientists and park managers; prey such as

possums and parrots; cohabitants and competitors such as birds that also use

hollows or attack owls because they see them as a threat. Beyond birds, plants,

parasitic microorganisms, and other forms of life are also important as

members of multispecies communities. Engagement with Indigenous peoples, cultures, and land-management practices can also be informative and is

ethically necessary for future design but remained beyond the scope of this

article.

3. Very brief engagement with extended timescales is another limitation. More

thorough exploration of past and possible circumstances at different timescales, from evolutionary to phenological and circadian, can further inform

design decisions. Our approach to deriving and documenting capabilities via

tables and diagrams serves as a useful and reusable base to extend these

investigations (Section 3.4.). As we discuss below, such investigations reveal

conflicts, practical and ethical challenges, and opportunities for design.

Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0

© 2022 V&R unipress | Brill Deutschland GmbH

�Parker/Soanes/Roudavski, Transpositiones (2022), Volume 01, 183-236, DOI 10.14220/trns.2022.1.1.236

208

4.2.

Transpositiones 1, 1 (2022)

The Ethical Challenges of Interspecies Design: Directions for Future

Research

Ethical issues of interspecies design warrant further conceptual and theoretical

consideration. Here, we discuss the potential challenges of deciding when and

why to intervene in the lives of others, who is entitled to design, what form the

design takes, and how design changes nonhuman lives.

Why, or under what circumstances, should designers intervene? Should interventions wait until a species is on the brink of extinction or aim to supplement

existing populations? One argument is that humans have a responsibility to assist

the animals they make dependent or influence through habitat destruction.92

Sceptics will call out the apparent irony of installing human-made habitats in

direct response to human-made habitat loss. Do financial provisions via ‘nature

offsets’ make habitat-designers complicit in destructive practices like housing

developments?93

Most will likely feel ambivalent when creating habitat structures that intend to

offset past or future habitat destruction. Yet, there is a need to imagine culturally

and ecologically sustainable futures that challenge the dominant, exploitative

economic systems.94 Even when designers might prefer systemic political and

economic change, immediate interventions such as nest boxes can serve as an

achievable measure that may help to avoid the extinction of certain species.

However, such actions could result in the emergence of nest-box-loving individuals who might speciate from their natural-hollow conspecifics, with undesirable results.

Some will argue that humans should stop interfering with others’ lives,

stressing that human-made habitats are band-aid solutions or last-resort

measures. This logic has merit but understates the value of human-made habitats

including bird houses and bee hotels as culturally significant artefacts that can

enhance human knowledge about and emotional connections with other species.

Further, arguments which presume the binary separation of humans and nature

are problematic. These separations break down under pervasive human impacts

in the Anthropocene or when exposed to the non-dualist worldviews and practices of Indigenous societies.95 Cities or other human-altered landscapes provide

92 Clare Palmer, Animal Ethics in Context (New York: Columbia University Press, 2010).

93 For further discussion on the ethics of offsets, see Christopher Ives and Sarah Bekessy, “The

Ethics of Offsetting Nature,” Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment 13, no. 10 (2015): 568–

73, https://doi.org/10/f 724z3.

94 Tony Fry, Design Futuring: Sustainability, Ethics and New Practice (Sydney: University of

New South Wales Press, 2009).

95 Lesley Head, Hope and Grief in the Anthropocene: Re-Conceptualising Human-Nature Relations, Routledge Research in the Anthropocene (New York: Routledge, 2016).

Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0

© 2022 V&R unipress | Brill Deutschland GmbH

�Parker/Soanes/Roudavski, Transpositiones (2022), Volume 01, 183-236, DOI 10.14220/trns.2022.1.1.236

Parker / Soanes / Roudavski, Interspecies Cultures and Future Design

209

critical habitat for many animals.96 This reality reiterates the need for design that

encourages mutually beneficial cultures between human and nonhuman cohabitants in cities.

Who is entitled to future design? Visions of more just futures require considerations of practices humans consider unjust, including the sufferers of this

injustice and ways to eliminate or remedy harms.97 Contentions occur when

simultaneously existing needs are not compatible. Examples include the interests

of current and future generations, preferences of individuals and collectives, or

misalignments between intrinsic and instrumental values.98 The provision of

habitat for target-species presents one such challenge. For example, human

support for powerful owls will impact other species such as possums. Some

conservationists target charismatic animals, often attempting to help wider

ecosystems via ‘umbrella species.’99 Research on speciesism contemplates cultural drivers that underpin human partiality for some species over others.100 In

the context of interspecies design, discourse on the ethics of selecting target