Like most handmade shoes from Northampton, England, Crocket & Jones’s footwear is beautiful and will last you a lifetime. I have visited the company’s factory, and it’s exactly what you’d expect from a 145-year-old English shoemaker: hulking and grand in a Dickensian way; scented by rich leathers and suedes, strong breakfast tea, and motor oil; staffed by highly skilled people that have plied their trade since they were teenagers.

But the shoes start around $650 and go up to almost $1,500. For most people that price is hard to even comprehend, let alone justify. So why does luxury footwear cost so much? And is there a way to find high quality without breaking the bank?

“A good-quality pair of shoes is defined by the materials used, the construction method, and the attention to detail in craftsmanship,” says Sebastian Öhrn, founder of the Swedish shoe brand Myrqvist, where a pair of handcrafted cap-toe calf-leather oxfords is a surprisingly low $319. A high-quality shoe begins with the leather, according to Öhrn. Full-grain calfskin—the kind of leather that’s light and supple—is preferred because it’s durable and develops an elegant patina over time, he adds.

The Details of a High-Quality Shoe

The construction of a shoe is a critical, Öhrn explains. One phrase in particular is a signifier of excellence: “Goodyear welt,” which refers to a labor-intensive shoemaking process that’s become a byword for quality. Simply put, a Goodyear welt is a layer of leather stitched between the upper (the body of the shoe) and the outsole (the hard material on the bottom of the shoe) that offers both a waterproof layer and the capacity to easily replace the outsole if and when it wears out.

You can find Goodyear-welted shoes at Edward Green, Carmina, John Lobb, Alden, all of which will be at the upper end of the price spectrum, around the $700 mark. But you can find welted shoes at Meermin ($200), Morjas ($380) and Dr. Martens ($150). Even J.Crew sells a Goodyear-welted derby for just over $200.

“It’s important to note that while the Goodyear welt is a strong indicator of quality, it’s not a guarantee,” says Öhrn, who suggests it can sometimes be used as a marketing tool. “Other construction methods, like Blake stitching [an alternative to Goodyear welting], can also produce a high-quality shoe when executed with the right materials and expertise.” Cult French brand Paraboot, for example, is a proud proponent of the “Norwegian” welt, which was first developed for hiking footwear.

But it takes more than a welt to make a great shoe. In cheaper shoes, interior leather components are often replaced with synthetic alternatives—in the heel construction, for example—and some use glue-based construction to cut corners. High-quality shoes will have a layer of cork beneath the insole, which is the part that touches your foot, for extra cushioning, as well as a “shank” of wood beneath the arch of the foot to maintain the shoe’s flexibility over time. A cheaper shoe will likely have neither.

Other details to look out for include a blunted “gentleman’s corner” on the inner corner of the heel, which is now redundant but was originally used to stop your pants cuff from snagging on your shoe. Öhrn also recommends a well-shaped last. The last is the master mold that the upper of each shoe is shaped around in the production process, and brands keep their various lasts secret. They’re like watch references or vintages of Champagne in that certain lasts are coveted more than others. Some are even famous. Crockett & Jones’s last 325, for example, has been around for more than two decades and is renowned for longevity and comfort. If you buy bespoke shoes (which will cost you thousands of dollars), you’ll have your own unique last that the shoe company—say, John Lobb—keeps indefinitely, ready for you to order your next pair.

A well-shaped last will have been created with care and consideration, designed either for all-round wear or for more specific foot shapes. When you’re buying expensive shoes, ask the salesperson about the last, what it offers, and how it differs from others in the range.

You should think about the sole, too. The assumption is that dress shoes have a thin leather sole and more casual or hard-wearing shoes have a “cleated” rubber sole. That is broadly true—you wouldn’t wear a rubber-soled shoe with a tux, for example—but not exclusively, and some of my favorite dress shoes are on a chunky rubber sole. In fact, I much prefer the durability (and extra half inch of lift) they offer. Paraboot is great for chunky soles, and British brands Tricker’s and Grenson have both explored more avant-garde sole shapes in recent years. The latter has a pair of brilliant new derbies in an “oily” brown suede ($550) that are particularly good.

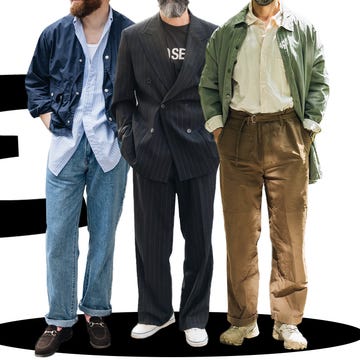

High-Quality Shoes for Less Than $400

Ultimately, you will have to spend some money for a really good pair of shoes. You could hunt down a pair of boots for less than $100, but the leather will be crap and the stitching (if there is any) will open up in no time at all. People—like me, for instance—talk easily and often about “investment” pieces, and it can be frustrating to be told that if you want a good thing, you have to spend a month’s wages. But there’s an old adage that goes, “Buy well, buy once,” and it is true when it comes to shoes.

The good news is there are high-quality shoes that won’t send you into crippling credit-card debt. Here are ten great pairs of dress shoes for under $400.