New Hispanic History Tool Can Help Us Learn More about Houston

The new Portal of Hispanic History created by the Queen Sofia Spanish Institute can teach us a lot.

If you’ve ever wondered how Galveston got its name, or who Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca is and why there’s a bronze bust of him at Hermann Park, you can now turn to a new resource that will help you dive into all your questions about the Hispanic history of Houston and Texas.

In May, the Queen Sofía Spanish Institute, a New York–based nonprofit founded in 1954 to foster the art, culture, and history of Spain, unveiled an online database called the Portal of Hispanic History, developed by the Royal Academy of History of Spain. The free digital platform highlights more than 20,000 Hispanic historical events, prominent figures, and locations of historical markers and statues across the globe.

A bronze bust of Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca in Hermann Park.

“The portal serves as a great tool to wander through history and time,” says Dr. Raúl Ramos, an associate professor in history at the University of Houston. “It’s a great way to see a connection to things that weren't obvious at first and how events, how people, and how history is connected, rather than existing in a bubble.”

Queen Sofía herself visited Houston last month for the U.S. debut of the Portal of Hispanic History, joined by mayor Sylvester Turner and academics, including Ramos. In the span of five years, the project’s team collected a multitude of digital archives and readings from more than 5,000 authors and historians. The portal can be seen as a developing digital library, and is the first of its kind to have mapped the history of an entire country.

Ramos says that a database as extensive as this is a great resource for researchers, students, and professors of various specialties, and just as interesting for fans of history in general. “I think everyday Houstonians will have an opportunity to see how their world is bigger,” he says. “You have Houstonians of Latino origin that can see their history as a larger historical experience that gives us a sense of historical place and significance, and for non-Latino Houstonians, it’s a way to connect the dots between American history and Hispanic history.”

When you open the portal’s homepage, you’ll see multiple markers scattered across a world map, and if you zoom into Texas, the Gulf of Mexico, or cities like Houston and San Antonio, you’ll find a variety of markers to explore. Whether it be the birthplace and death of a historical Spanish figure or a battle that took place at any point in time, the information is as available as it is at a public library.

Galveston is named after the Spanish Colonial governor Bernardo de Galvez.

For example, Galveston, previously known as “Galvez Town,” got its name from the Spanish Colonial governor Bernardo de Galvez, who despite being the town’s namesake, never once set foot on the island. Galvez ordered the first survey of the Texas Gulf Coast in 1786 and the surveyor, José de Evia, named Galveston Bay in his honor.

Before Galvez, there was Spanish explorer Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, who arrived on the coast near Galveston in 1528 and gave Galveston the name "Mal Hado," which roughly translates to “The Isle of Misfortune.” Today, a bronze bust of Cabeza de Vaca on a granite pedestal lives in Hermann Park, created by Pilar Cortella de Rubin, a Spanish native who lived in Houston.

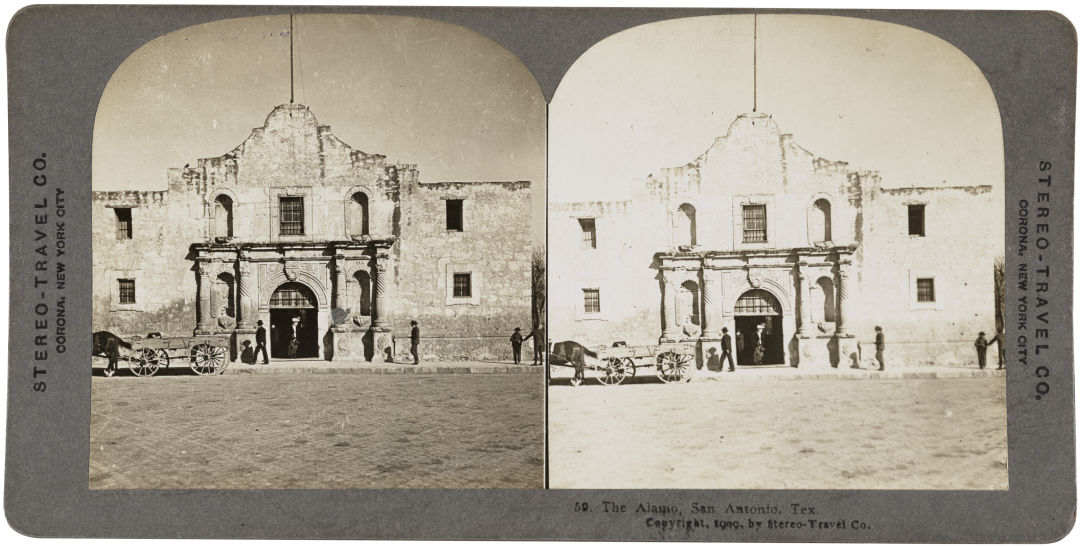

The Alamo building has plenty of history even before the famous Battle of the Alamo.

Image: Courtesy Library of Congress

In San Antonio, Fray Antonio de Olivares founded the first mission in Texas along the San Antonio River in 1718, what is known today as Mission El Alamo. The Alamo building’s history that occurred over a century before the famous Battle of the Alamo can be found within the portal.

Of course, the reality of Spain’s history and its impact on the world is also a story of colonization, occupation, and genocide. Ramos believes that the portal itself does not appear to be interpretive, analytical, or political, and instead acknowledges all aspects of history.

The portal provides examples of battles and attacks by Spanish settlers and soldiers on Indigenous communities in the Southwest, and examples of peace treaties and missions that showcase some coercion mixed with cooperation. It also makes note of Indigenous communities prior to Spanish conquest.

“You’ll find examples of all of these types of experiences and anyone that approaches it can bring their own questions and understanding to it,” Ramos says. “The nature and intent of the portal is to continue to expand and grow, and looking at the dynamics of Spanish-Indigenous contact in the first centuries is one area where the expansion could be very fruitful.”

For new users to the portal who have no idea where to begin, Ramos says there are many ways to approach it, but suggests starting with a place of interest. “When you see a marker of where someone died, that’s just the start of the journey,” he says. “How did they get there? What were they doing there? Who are they connected with? What era and period in time? That’s the kind of curiosity that just one place on the map can lead you. There are a lot of possibilities.”